Since it hit 1,000,000% in 2018, Venezuelan hyperinflation has actually been not only continuing but accelerating. Recently, Venezuela’s annual inflation hit 10 million percent, as predicted by the IMF; the inflation jumped so quickly that the Venezuelan government actually struggled to print its constantly-inflated money fast enough. This may seem unbelievable, but peak rates of monthly inflation were actually higher than this in Zimbabwe (80 billion percent/month) in 2008, Yugoslavia (313 million percent/month) in 1994, and in Hungary, where inflation reached an astonishing 41.9 quadrillion percent per month in 1946.

The continued struggles to reverse hyperinflation in Venezuela are following a trend that has been played out dozens of times, mostly in the 20th century, including trying to “reset” the currency with fewer zeroes, return to barter, and turning to other countries’ currencies for transactions and storing value. Hyperinflation’s consistent characteristics, including its roots in discretionary/fiat money, large fiscal deficits, and imminent solvency crises are outlined in an excellent in-depth book covering 30 episodes of hyperinflation by Peter Bernholz. I recommend the book (and the Wikipedia page on hyperinflations) to anyone interested in this recurrent phenomenon.

However, I want to focus on one particular inflationary episode that I think receives too little attention as a case study in how value can be robbed from a currency: the 3rd Century AD Roman debasement and inflation. This involved an iterative experiment by Roman emperors in reducing the valuable metal content in their coins, largely driven by the financial needs of the army and countless usurpers, and has some very interesting lessons for leaders facing uncontrollable inflation.

The Ancient Roman Currency

The Romans encountered a system with many currencies, largely based on Greek precedents in weights and measures, and iteratively increased imperial power over hundreds of years by taking over municipal mints and having them create the gold (aureus) and silver (denarius) coins of the emperor (copper/bronze coins were also circulated but had negligible value and less centralization of minting). Minting was intimately related to army leadership, as mints tended to follow armies to the front and the major method of distributing new currency was through payment of the Roman army. Under Nero, the aureus was 99% gold and the denarius was 97% silver, matching the low debasement of eastern/Greek currencies and holding a commodity value roughly commensurate with its value as a currency.

The Crisis of the Third Century

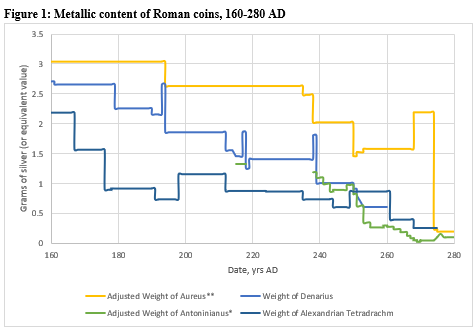

However, a major plague in 160 AD followed by auctions of the imperial seat, major military setbacks, usurpations, loss of gold from mines in Dacia and silver from conquest, and high bread-dole costs drove emperors from 160-274 AD to iterative debase their coinage (by reducing the size and purity of gold coins and by reducing the silver content of coins from 97% to <2%). A major bullion shortage (of both gold and silver) and the demands of the army and imperial maintenance created a situation where a major government with fiscal deficits, huge costs of appeasing the army and urban populace, and diminishing faith in leaders’ abilities drove the governing body to vastly increase the monetary volume. This not only reflects Bernholz’ theories of the causes of hyperinflations but also parallels the high deficits and diminishing public credit of the Maduro regime.

Inflation and debasement

Unlike modern economies, the Romans did not have paper money, and that meant that to “print” money they had to debase their coins. The question of whether the emperor or his subjects understood the way that coins represented value went beyond the commodity value of the coins has been hotly debated in academic circles, and the debasement of the 3rd century may be the best “test” of whether they understood value as commodity-based or as a representation of social trust in the issuing body and other users of the currency.

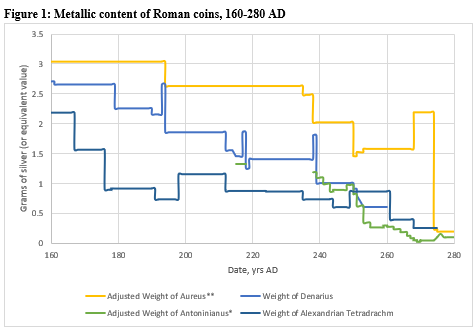

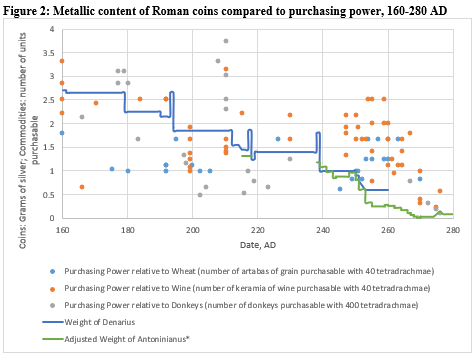

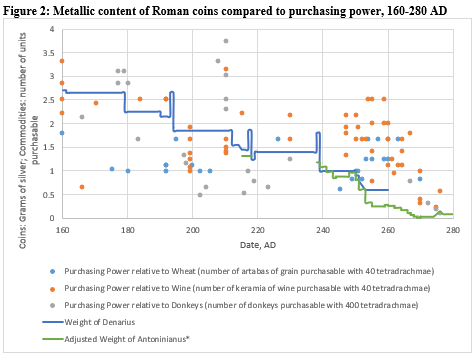

Given that the silver content of coins decreased by over 95% (gold content decreased slower, at an exchange-adjusted rate shown in Figure 1) from 160-274 AD but inflation over this period was only slightly over 100% (see Figure 2, which shows the prices of wine, wheat, and donkeys in Roman Egypt over that period as attested by papyri). If inflation had followed the commodity value of the coins, it would have been roughly 2,000%, as the coins in 274 had 1/20th of the commodity value of coins in 160 AD. This is a major gap that can only be filled in by some other method of maintaining currency value, namely fiat.

Effectively, a gradual debasement was not followed by insipid ignorance of the reduced silver content (Gresham’s Law continued to influence hoards into the early 3rd Century), but the inflation of prices also did not match the change in commodity value, and in fact lagged behind it for over a century. This shows the influence of market forces (as monetary volume increased, so did prices), but soundly punctures the idea that coins at the time were simply a convenient way to store silver–the value of the coins was in the trust of the emperor and of the community recognition of value in imperial currency. Especially as non-imperial silver and gold currencies disappeared, the emperor no longer had to maintain an equivalence with eastern currencies, and despite enormous military and prestige-related setbacks (including an emperor being captured by the Persians and a single year in which 6 emperors were recognized, sometimes for less than a month), trade within the empire continued without major price shocks following any specific event. This shows that trust in the solvency and currency management by emperors, and trust in merchants and other members of the market to recognize coin values during exchanges, was maintained throughout the Crisis of the Third Century.

Imperial communication through coinage

This idea that fiat and social trust maintained higher-than-commodity-values of coins is bolstered by the fact that coins were a major method of communicating imperial will, trust, and power to subjects. Even as Roman coins began to be rejected in trade with outsiders, legal records from Egypt show that the official values of coins was accepted within the army and bureaucracy (including a 1:25 ratio of aureus-to-denarius value) so long as they depicted an emperor who was not considered a usurper. Amazingly, even after two major portions of the empire split off–the Gallic Empire and the Palmyrene Empire–continued to represent their affiliation with the Roman emperor, including leaders minting coins with their face on one side and the Roman emperor (their foe but the trusted face behind Roman currency) on the other and imitating the symbols and imperial language of Roman coins, through their coins. Despite this, and despite the fact that the Roman coins were more debased (lower commodity value) compared to Gallic ones, the Roman coins tended to be accepted in Gaul but the reverse was not always true.

Interestingly, the aureus, which was used primarily by upper social strata and to pay soldiers, saw far less debasement than the more “common” silver coins (which were so heavily debased that the denarius was replaced with the antoninianus, a coin with barely more silver but that was supposed to be twice as valuable, to maintain the nominal 1:25 gold-to-silver rate). This may show that the army and upper social strata were either suspicious enough of emperors or powerful enough to appease with more “commodity backing.” This differential bimetallist debasing is possibly a singular event in history in the magnitude of difference in nominal vs. commodity value between two interchangeable coins, and it may show that trust in imperial fiat was incomplete and may even have been different across social hierarchies.

Collapse following Reform

In 274 AD, after reconquering both the Gallic and Palmyrene Empire, with an excellent reputation across the empire and in the fourth year of his reign (which was long by 3rd Century standards), the emperor Aurelian recognized that the debasement of his currency was against imperial interests. He decided to double the amount of silver in a new coin to replace the antoninianus, and bumped up the gold content of the aureus. Also, because of the demands of ever-larger bread doles to the urban poor and alongside this reform, Aurelian took far more taxes in kind and far fewer in money. Given that this represented an imperial reform to increase the value of the currency (at least concerning its silver/gold content), shouldn’t it logically lead to a deflation or at least cease the measured inflation over the previous century?

In fact, the opposite occurred. It appears that between 274 AD and 275 AD, under a stable emperor who had brought unity and peace and who had restored some commodity value to the imperial coinage, with a collapse in purchasing power of the currency of over 90% (equivalent to 1,000% inflation) in several months. After a century in which inflation was roughly 3% per year despite debasement (a rate that was unprecedentedly high at the time), the currency simply collapsed in value. How could a currency reform that restricted the monetary volume have such a paradoxical reaction?

Explanation: Social trust and feedback loops

In a paper I published earlier this summer, I argue that this paradoxical collapse is because Aurelian’s reform was a blaring signal from the emperor that he did not trust the fiat value of his own currency. Though he was promising to increase the commodity value of coins, he was also implicitly stating (and explicitly stating by not accepting taxes in coin) that the fiat value that had been maintained throughout the 3rd Century by his predecessors would not be recognized going forward by the imperial bureaucracy in its transactions, thus signalling that for all army payment and other transactions, the social trust in the emperor and in other market members that had undergirded the value of money would now be ignored by the issuing body itself. Once the issuer (and a major market actor) abandoned fiat currency and stated that newly minted coins would have better commodity value than previous coins, the market–rationally–answered by moving quickly toward commodity value of the coins and abandoned the idea of fiat.

Furthermore, not only were taxes taken in kind rather than coin, but there was widespread return to barter as those transacting tried to avoid holding coins as a store of value. This pushed up the velocity of money (as people abandoned it as a store of value and paid higher and higher amounts for commodities to get rid of their currency). The demonetization/return to barter reduced the market size that was transacted in currency, meaning that there were even more coins (mostly aureliani, the new coin, and antoniniani) chasing fewer goods. The high velocity of money, under Quantity Theory of Money, would also contribute to inflation, and the unholy feedback loop of decreasing value causing distrust, which caused demonetization and higher velocity, which led to decreasing value and more distrust in coins as stores of value kept this cycle going until all fiat value was driven out of Roman coinage.

Aftermath

This was followed by Aurelian’s assassination, and there were several monetary collapses from 275 AD forward as successive emperors attempted to recreate the debased/fiat system of their predecessors without success. This continued through the reign of Diocletian, whose major reforms got rid of the previous coinage and included the famous (and famously failed) Edict on Maximum Prices. Inflation continued to be a problem through 312 AD, when Constantine re-instituted commodity-based currencies, largely by seizing the assets of rich competitors and liquidating them to fund his army and public donations. The impact of that sort of private seizure is a topic for another time, but the major lesson of the aftermath is that fiat, once abandoned, is difficult to restore because the very trust on which it was based has been undermined. While later 4th Century emperors managed to again debase without major inflationary consequences, and Byzantine emperors did the same to some extent, the Roman currency was never again divorced from its commodity value and fiat currency would have to wait centuries before the next major experiment.

Lessons for Today?

While this all makes for interesting history, is it relevant to today’s monetary systems? The sophistication of modern markets and communication render some of the signalling discussed above rather archaic and quaint, but the core principles stand:

- Fiat currencies are based on social trust in other market actors, but also on the solvency and rule-based systems of the issuing body.

- Expansions in monetary volume can lead to inflation, but slow transitions away from commodity value are possible even for a distressed government.

- Undermining a currency can have different impacts across social strata and certainly across national borders.

- Central abandonment of past promises by an issuer can cause inflationary collapse of their currency through demonetization, increased velocity, and distrust, regardless of intention.

- Once rapid inflation begins, it has feedback loops that increase inflation that are hard to stop.

The situation in Venezuela continues to give more lessons to issuing bodies about how to manage hyperinflations, but the major lesson is that those sorts of cycles should be avoided at all costs because of the difficulty in reversing them. Modern governments and independent currency issuers (cryptocurrencies, stablecoins, etc.) should take lessons from the early stages of previous currency trends toward trust and recognition of value, and then how these can be destroyed in a single action against the promised and perceived value of a currency.