For those who are unaware, I’ve been one of the hosts of the Center for a Stateless Society’s flagship podcast Mutual Exchange Radio for a number of years now. Our latest episode features Kevin Carson discussing the role of theory and history in the debate between Austrian and Historicist economists, as well as touching on the American institutionalist school, the role of interest and credit in mutualist banking (an issue with which I disagree with Carson, as you will see), absentee landlordism and more. The touchstone for our conversation was his 2021 C4SS study on the topic. You can listen to it wherever you get your podcasts, or on C4SS’s website.

Economics and the Mirror of Nature

Editorial Note: This is an old and longform essay I wrote on the philosophy of economics and economic methodology originally for a history of economic thought class as a sophomore undergraduate at Hillsdale College back in April of 2015. I am uploading it here mostly for posterity as a historical interest in my own intellectual development and for any curious onlookers interested in what interpretive economic social theory could look like–at least at a high, sketchy and not detailed level.

It is worth noting that there is an obvious thing I should have done differently: it really should have treated the “ecological rationality” of figures like Vernon Smith and the later FA Hayek as a fourth alternative paradigm to the sort of rationality practiced by neoclassicals, the interpretive rationality practiced by some Austrians and the Bounded Rationality practiced by behavioral economists. This ecological notion of rationality which makes room for neoclassical-style constructivist theories of rationality–so long as they are understood as maps and not the terrain–is something I am more sympathetic towards these days alongside the intepretive, hermeneutic sort of rationality argued for in this essay.

I still think it gets a lot of the genealogical and psychological diagnosis of what historically has gone wrong in economic questions about rationality as developed by neoclassical, behavioral, and Misesean Austrian economics by relying too much on an unquestioned epistemic foundationalism , but I think normative pragmatists like Robert Brandom offer us a more constructively and ecologically critical way forward than I was aware of when I penned this paper.

The essay is presented here largely as it was originally written, with only minimal editing. Its sophomoric sketchiness, grand but unrealized ambitions, and rough edges are intact.

Economics and the Mirror of Nature: Richard Rorty’s Hermeneutics as an Approach to the Historical Study of Rationality in Relation to Economic Theory and Method

The conception of man as a “rational actor” is one of the key foundations of modern economic thinking. However, what exactly economists mean by “rationality” in the technical sense has historically been a fairly sticky issue that has evolved as economic theory has evolved. In some ways, rationality is tied up with epistemological problems in economic methodology. In other ways, it has been tied to value theory, expectations theory, and a host of other issues that seem like pure theoretical theory than meta-economic questions of method. However, a historical treatment of how economists have come to understand rationality deserves sensitivity to how economists have understood internal problems to economics itself and the relationship to the nature of the economic science.

FA Hayek (1952) lays out the potential for a progressive research program in the history of thought in the social sciences in his work Counterrevolution of Science. For Hayek, “scientism,” viewing the research program of the social sciences as essentially the same as the natural sciences, is prevalent the intellectual discourse about the social sciences. Hayek objects to “the objectivism of the scientistic approach” insofar as it treats the data of the social sciences as fundamentally the same as the data of the physical sciences, objective, measurable phenomena. For Hayek, this leads to “rationalist constructivism” in approach to solving the problems of society. Examples of “rationalist constructivism” include most primarily August Comte’s approach to social engineering and sociology and socialist attempts to design economies.

In a similar vein, Richard Rorty’s Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature (1980) objects to what he calls the “Platonic Kantian” approach to philosophy. For Rorty, the “image of the mind as a great mirror, containing various representations—some accurate, some not—and being capable of being studied by pure, nonempirical methods” (12) has lead philosophy astray into a series of non-constructive topics such as philosophy of mind and philosophy of language in which philosophers tried to “ground” all of knowledge in a way that every rational being could agree.

This paper proposes that FA Hayek’s program of “rational constructivism” should be viewed as a complementary approach to Richard Rorty’s program in the history of philosophy as laid out in the Mirror of Nature. Following the tradition of Lavoie (1990), this paper argues that a hermeneutical exegesis of economics as a whole, not simply one or the other tradition, might help bring the various “schools” of economics into better dialogue with each other. The first part lays out a partial history of one subject, utility theory, in which economics has attempted to objectify itself into the realm of natural science drawing heavily off of Zouboulakis’ Varieties of Economic Rationality (2013). The second part argues that Rorty’s hermeneutical approach can explain the historical narrative in a Hayekian way. A concluding section reflects on areas needed for further research.

Part 1: Our Utilitarian Essence

One of the fundamental assumptions, especially of the English school during the marginal revolution, in the formation of the economics science as we know it today was presupposing a fairly simple psychology of utilitarianism drawing from Bentham. However, this idea of utility theory as foundational to economics was eventually replaced by Pareto’s ordinal approach to utility theory. The title of this section draws from the title of the first section of Rorty’s Mirror of NatureL “Our Glassy Essence,” which reflects on how the image of “the mind as mirror” came into existence. This section lays out how utility came to be viewed as “essential” to the meaning of economics

Rationality as Utility Maximization: Jevons and the English Marginal Revolution

When economists say “rationality,” they have always intended it as a term of art. Thus phrases such as “rational action,” “rational actor,” and “rationality” in the technical economic sense have never really meant what is thought by these phrases in the everyday sense. In the everyday sense, what is typically meant by “rational” is that one is holding a belief based on reasonable evidence. However, for early economists rationality has always been tied up with some sense of individualized self-interest.

The most primitive version of rationality as an economic term of art was found in the work of classical political economist and utilitarian philosopher Jerome Bentham. For the early nineteenth century economists, to be rational was to maximize utility in the Benthamite sense; to maximize pleasure and minimize pain in a very broad sense. Thus early economic ideas of a rationally self-interested actor were intimately related to utility. An example of this idea of rationality as pursuit of utility is the work of William Jevons. Though Jevons never used the term “rationality,” it is clear in his work that the concept today called “rationality” is very central to Jevon’s work. Jevons adopted a very strong conception of rationality in line with homo economicus.

In order to understand how Jevons conceived of economics, it is important to understand its place in his broader context of economic thought on economic method. In his Theory of Political Economy (1871/2013),Jevons claimed that “Economics, if it is to be a science at all, must be a mathematical science” (434). This is largely because Jevons had a strong commitment to making economics analogous to physics. As he wrote in the first edition of TPE (1871/2013):

The theory of economy, thus treated, presents a close analogy to the science of Statistical Mechanics, and the Laws of Exchange are found to resemble the Laws of Equilibrium of a lever as determined by the principle of virtual velocities. (cited in Zouboulakis 2013, 26).

Unlike physics, however, Jevons claimed economics was “peculiar” because “its ultimate laws are known to us first by intuition, or at any rate they are furnished to us ready made by other mental or physical sciences” (cited in Zouboulakis 2013, 30).

As Zouboulakis (2013) notes, a very strong conception of rationality Jevons insisted upon almost axiomatically was necessary to give economics this extreme level of mathematical and scientific rigor. In order to make rationality such a strong concept, Jevons would rely upon a Benthamite utilitarian theory with a heavily scientific flavor. He argued the idea that people maximize pleasure and avoid pain is an “obvious psychological law” on which “we can proceed to reason deductively with great confidence” (cited in Zouboulakis 2013, 30-31). For Jevons (1871/2013), “pleasure and pain bare undoubtedly the ultimate objects of the Calculus of Economics” (440). Utility, therefore, is the the central object of Jevon’s economic inquiry. Jevons, quoting Bentham, defines as “that property in any object, whereby it tends to produce benefit, advantage, pleasure, good, or happiness” (1871/2013, 438). Jevons maintains a concept of “total utility” (440) that may be “estimated in magnitudes” (435). This idea of rationality is, to quote Herbert Simon (1978) “omniscient,” meaning is there is little to no concept of uncertainty, limited information, or psychological error taken into account in how people pursue rational self-interest, it is simply a law of psychology that people always seek to maximize utility, a law that is central for his understanding of economics as a science.

Jevons was not alone in his strong conception of understanding of rationality as a maximization principle. Zouboulakis (2013) argues that Cournot, Walras, and Marshall, all shared a similar conception of rationality to Jevons (35). In fact, Walras (Zouboulakis 2013) in line with Jevons adopted a strong conception of economics as another sort of mathematical physics. Edgeworth (1881/2013), though he doubted that Jevons was entirely correct on to what extent total utility was quantifiable still generally adopted the utilitarian outlook Jevons had assumed, as well as the mathematical outlook as he extensively compared it to physics (504-505).

To summarize, the concept of rationality as formulated by Jevons consists of the following four unique theoretical features:

- Defined as a maximization of total cardinal utility

- United with a psychological hypothesis

- Irrefutable, obviously true about human nature

- Assumes omniscience

It is dependent on another methodological feature: that economics is to be viewed mathematically and analogous to physics on some important level. It is important to note, however, that the early neoclassical economists were not wholly homogeneous in their outlook of economics as a science. Alfred Marshall argued that “economics cannot be compared with the exact physical sciences: for it deals with the ever changing and subtle forces of human nature” (qtd. in McKenzie 2009). Though Marshall’s conception of rationality was still largely in line with Jevons, his softer methodological positions would allow for a softening of rationality as a concept after the marginal revolution.

Rationality asInstrumentalism: Pareto’s Departure from Utility Theory

In addition to the concept of economics as a completely mathematical science, other assumptions that led to Jevon’s omniscient conception of rationality would be threatened. After the marginal revolution, primary cornerstones of how Jevons conceived of rationality, cardinal utility as a quantifiable concept, would be rejected by the economics profession. The key insight from Jevon’s subjective utility theory was his marginal analysis, his insight from the theory of exchange that consumers seek to equilibrate the ratios between the marginal utilities (what Jevons calls the “degree of utility”) of goods.

Though Jevon’s conception of total utility “constituted the metaphysical foundation of utilitarian economics, neither [its] measurement nor even their existence was central to their methods” (Read 2004). At the dawn of the twentieth century, Pareto had brought about the ordinal revolution. Any reference to “cardinal utility,” that is utility as a measurable concept, was completely removed. Instead, for Pareto, any measurable cardinal utility was replaced by ordinal utility—utility as a relative comparison of some basket of goods (cited in Read 2004).

With the change in utility followed a change, in the conception of rationality. Since one of the key theoretical implications of Jevon’s rationality thought was disproven, economists could greatly weaken what they meant by rationality. First, Pareto distanced rationality from being any sort of an axiomatic psychological claim. He did this by adopting a more positivist, experimental approach to economics, he declared “I am a believer in the efficiency of experimental methods. For me there exist no valuable demonstrations except those that are based on facts” (cited in Zouboulakis 2013, 37). However, given his rejection of cardinal utility, the hypothesis that rational actors can maximize utility becomes meaningless and untestable since it is unclear what they are maximizing (Zouboulkis 2013, 38). As Pareto said, “Let us suppose that we have a schedule of all possible choices indicating the order of preference. Once this schedule is available, homo œconimicus can leave the scene” (cited in Zouboulakis 2013, 38).

Instead, Pareto focuses only on the “facts” which he asserts are “the sales of certain goods and certain prices” (cited in Zouboulakis 2013, 38). In other words, Pareto is only concerned with the impact of rational choice theory in a market setting, not with the psychology behind those facts. For Pareto, then, “rationality is simply a choice of efficient means for serving any independently given objective,” Zouboulakis (2013) calls Pareto’s an “instrumental” conception of rationality (38).

For Pareto, contra Jevons, the extent to which rationality was wholly applicable to all of humanity was extremely limited. In his later works, he made a strong distinction between “logical” and “non-logical actions.” As Zaboulkis (2013, 39-41) puts it, logical actions are those in which the “subjective aim of the actor is reasonably connected with the action’s objective goal,” whereas everything else are things that man do not have control other such as psychological factors that an economist takes as given. This greatly limits the extent of human action that economics studies from Jevon’s attempts to universalize utilitarian psychological hypotheses.

To summarize, Pareto’s conception of rationality has the following theoretical features:

- Non-psychological

- Given within a means-ends framework (Instrumental)

- Non-universal, non-omniscient

Rationality as Purposeful Action: Mises’ Austrian Tautology

While Pareto had developed a fairly weak conception of rationality in contrast to Jevons, a separate tradition in the Austrian school of economists had developed a similar, though different, conception of rationality. This latter type of rationality is the conception primarily taken up by Ludwig von Mises and Carl Menger. In order to understand the Austrians, it is important to understand the historical context it was born out of in contrast to Pareto. Pareto was primarily influenced by Anglophonic and Francophonic marginalists, and had inherited from that tradition a strong conception of rationality wedded to cardinal utility that he had to soften with ordinal utility. In contrast, Mises had inherited the marginal utility theories of Menger (which included no reference to “total utility” as a cardinal concept to begin with), and had participated in the climate of the Methodenstreit which had placed heavy emphasis on theoretical methodology. Because of this, Mises’ idea of rationality bears resemblance to Pareto in important ways, however differs because of Mises’ and Pareto’s differing methods.

For Mises, to say that man is a rational actor is a tautological truth, he claims that “[h]uman action is necessarily rational” (1949/1998 18-19).[1] Though this sounds like a universalist claim found in Jevons, it is fundamentally different. For Mises to be a rational actor is not a psychological hypothesis, it simply means that man acts, or that he “the employment of means for the attainment of ends” (13). To be rational is simply to act purposefully, not to choose anything that an economist would normatively say one should chose such as maximization of cardinal utility.

It is important to note that unlike Jevons, the Austrian school adopted from the outset that rational actors are not omniscient. As Menger argued in his first statement of subjective value theory:

Even individuals whose economic activity is conducted rationally, and who therefore certainly endeavor to recognize the true importance of satisfactions in order to gain an accurate foundation for their economic activity, are subject to error. Error is inseparable from all human knowledge. (148)1

Likewise, Mises devoted a whole chapter of his magnum opus (1949/1998) to the concept of uncertainty (105-118).

It may be seen that there is a certain overlap between Mises’ idea of rationality and Pareto’s. Both have significantly weaker ideas of rationality than is implied by the utilitarians, and both distinguish economic rationality very carefully from psychology. For Mises, this means defining action as rational and defining its opposite “not irrational behavior, but a reactive response to stimuli” (1949/1998, 20). For Pareto, this means distinguishing between logical action and non-logical action and applying economic rationality only to the former.

However, there are important differences between Pareto and Mises: namely, Mises universalizes rationality as applied to all human action, Pareto does not. This is primarily due to differences in what is meant by “action,” Mises tautologically defines all action as rational, whereas Pareto simply makes action an instrument that is applied to a means-end framework. Thus, for Mises rationality defines the means-ends framework, for Pareto it is a tool that helps men pursue ends. The reason for this difference lies in their different views on economic methodology. Recall that Pareto is only concerned with facts that can be experimentally derived. However, Mises includes tautologies as an important part of his economic method which he calls “methodological a priorism” (1949/1998). Mises claims “tautologies” are helpful in providing “cognition” and “comprehension of living and changing reality” (38). Whereas Pareto would have scoffed at Mises idea of rationality as useless, for Mises it was a helpful a priori assumption for economic analysis, or in his terms “praxeological reasoning.”

To summarize, Mises’ weaker idea of rationality is marked by the following three qualities and assumes an a priorist methodological background:

- Rationality defines a means-end framework (is tautological)

- Is universal by a non-omniscient definition

- Non-psychological

The extent to which Mises’ idea of theory can be thought of as “foundational” to the rest of his social science is disputable. Clearly, Mises thought his theory was absolutely foundational, however that need not be the “foundation” of the rest of his economics. Zoboukalis seems to oversimplify in claiming that there’s a fundamental difference between Weber’s conception of an “ideal type” of rationality as universal and Mises’ conception of rationality as to some extent tautological. Boettke and Leeson (2006) claim that Mises rejected the analytic/synthetic distinction, thereby placing him in a more complex position than simple Kantian epistemology. However, Boettke, Lavoie, and Storr (2001) claim that Mises’ distinction between theory and history was “arbitrary” and use the philosophy of John Dewey to argue against it.

Rationality: How Lionel Robbins Misunderstood Mises, How Hayek Challenged Mises

The extent to which there is a universal “Austrian” conception of rationality is also disputable. Zaboukalis understands this in comparing the rationality of FA Hayek to Mises. Zaboukalis argues that Robbins presented Mises’ concept of rationality as “consistency” for a normative ideal in his work The Nature and Significance of Economic Science. This is supportable when Robbins (1932/2005 140) says:

There is nothing in its generalisations which necessarily implies reflective deliberation in ultimate valuation. It relies upon no assumption that individuals act rationally. But it does depend for its practical raison d’etre upon the assumption that it is desirable that they should do so. It does assume that, within the bounds of necessity, it is desirable to choose ends which can be achieved harmoniously.

Mises’ welfare economics clearly do not include all the presumptions that consistent action is “normative” that Robbins’ neoclassical misinterpretation of Mises presupposes. Mises explicitly says in Human Action that man’s preferences are situated in time and therefore are inconsistent over time. Mises places emphasis on man’s preferences as situated in time and uncertainty, Robbins makes the preferences sound as if they are independent of time and uncertainty in every sense.

Rizzo (2013) puts emphasis on how Mises postulated the meaning of economics to be primary. This passage is worth quoting at length:

First, we must distinguish between the meaning of behavior and criteria for the rationality of behavior. Abstract criteria of rationality cannot be applied without first understanding what individuals mean by what they do. Getting the meaning wrong may result in inaccurately labeling the behavior as irrational.

In Zoboukalis’ presentation, this lead Samuelson (1938) to present his revealed theory of preferences, which included the assumption of invariance, in Economica. Samuelson seems to have misunderstood Robbin’s misunderstanding of Mises on an even deeper level. In 1937 which Zoboukalis presents as “the year of uncertainty,” there were several challenges to Mises, one of which included Hayek’s challenge to Mises in Economics and Knowledge (cited in Zoboukalis, 1938). Kirzner (2001 81-89) argues that Hayek misunderstood what Mises thought about rationality. Mises did not take invariance through time to be normative, he took it to be positive at a particular instance.

Economics without Constancy in Utility: Preference Theory, Behavioral Economics as Paradigms aiming to be “Successor Subjects”

In response to the challenges to invariance raised by Hayek, Friedman and Samuelson, Zoubakalis argues, made a defense of the normative criterion of rationality, which became standard in the “neoclassical synthesis.” This was primarily the “as-if” methodology of Friedman which Austrians find so objectionable. In the research program of this paper, Lavoie’s (1980) hermeneutical way of dealing with the problem of pure methodological instrumentalism will be an issue. Lavoie argues for a way of doing economics without epistemic foundationalism, drawing directly off Rorty. The extent to which there is a balance established between what Lavoie sees as the crude epistemic foundationalism of Freidman’s positivist approach and the possibly foundationalist a priori approach of Mises will be perhaps the main focus of further research in this program. However, unlike Lavoie, the Hermeneutics will be more likely drawn directly from Rorty than Gadamer.

After Freidman, the invention of behavioral economics in Kahneman and Tverskey challenged several of the positive assumptions of neoclassical theory. Kahneman (2012) describes the Chicago school’s views on the matter in relation to the behavioral economic one as follows:

The only test of rationality is not whether a person’s beliefs and preferences are reasonable, but whether they are internally consistent. A rational person can believe in ghosts so long as all her other beliefs are consistent with the existence of ghosts. A rational person can prefer being hated or being loved, so long as his preferences are consistent. Rationality is logical coherence, reasonable or not. Econs are rational by this definition but there is overwhelming evidence that humans cannot be.

In modern neo-classical economics, which has incorporated Kahneman’s theories of loss aversion and hyperbolic discounting as mathematically as possible, this is an oversimplification. However, there is reason to believe that the rigid formalism of modern Chicago economics may or may not be consistent with the best means of developing a research program, however useful it might be in many contexts.

Recent scholarship on the relationship between behavioral economics and neoclassical theory has tried to figure out how to get past utility without invariance through time. This issue suggests there is no such thing as “true preferences” as Pareto, Samuelson, and Friedman implicitly assumed. Stigler (1977), in violation of typical Chicago school method posited a way of assuming there were “true preferences” by making appeal to the possibility that our preferences are developed into some preferences everyone could agree on in time. For example, one who tastes wine initially might not know what they are doing; however, with time, they become a wine connoisseur, and in general wine connoisseur agree on their preferences. Drawing of Stigler, Robb (2009) draws of Nietzsche’s psychology to further support Stigler’s theories. Heckman (2009), in a comment on Robb’s paper responded in typical neoclassical fashion, claiming the psychological theories of Neitzsche can be made endogenous in the neoclassical model with some mathematical tweaks. Robb made some amazingly insightful comments in response:

However, I am not prepared to take the easy way out and fully accept (R1) as Nietzschean Economics. Sticking with Occam’s razor, I would propose, as an alternative to (R1), that our engagement with time is twofold and a portion of it lies outside of pleasure maximization. While lacking the precision of fully specified models, the WTP approach gives specific predictions that are useful in practical problems in economics. Nietzsche, along with Heraclites, Kierkegaard, Hegel and Bergson, was the philosopher of becoming – whether I have expressed the point with any useful clarity at all, he should have a great deal to teach us.

I should acknowledge that Nietzschean Economics has a personal objective beyond explaining various phenomena in economic life. I wanted to arrive at a “framework for modeling intertemporal choice that is more closely aligned with our immediate experience.” A formative event for me was a yearlong spell of unemployment in 2001 after leaving a job managing the global derivatives and securities business of Japan’s largest bank. I was looking forward to inputting some ti, ei, Xi and realizing U(Z). But when my unexamined faith in U(Z) was put to the test, it did not turn out like I expected. Without obstacles to overcome, I discovered that the day is long. I got back to work. I believe my experience is not uncommon.

Rizzo (2012), meanwhile, draws on three ways Austrians in general have tried to reconcile the balance between psychology and economics. Rizzo draws off of Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language, Schutz’s phenomenological sociology, and Hayek’s gestalt psychology in The Sensory Order.

What is striking about Robb’s “Nietzschean economics” and Rizzo’s work on Austrian economics is they are two economists from two very different schools doing the same exact thing Rorty attempted to do with epistemology in the 70s. Much as there was an aversion to psychology in economics throughout the early formulations of utility theory, in philosophy there was an eversion to implementing psychology into epistemology because epistemology conceived of itself as the epistemic foundation on which all of philosophical knowledge stood. Likewise, economists have been reluctant to let any psychology into their utility theories at all. Rorty proposed a form of “behavioral epistemology” modeled after the work of William James, however Rorty proposed that “behavioral epistemology” should not be thought of as foundational to the philosophical project as a whole. “Behavioral economics” has, from a neo-pragmatist perspective, committed the sin Rorty avoided in trying to be the new foundation of preference theory and choice theory.

Just as Rorty was skeptical extensively in Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature” about “successor subjects” such as philosophy of mind and language attempting to be substitutes for Kantian epistemology as the foundation of all of philosophical, economists should be skeptical of possible “successor subjects” to Jevons-style utility theory in economics. Pareto once famously described his war against the English School as a war against “(t)hose who have a hankering for metaphysics” (McLure 199 312). Preference theory, behavioral experiments, and even Neitzschean psychology in Robb’s formulation could be viewed as merely “successor subjects” to Jevon’s ordinal utility theory. Just as Rorty claimed philosophers clung to “our glassy essence” in Kantian epistemology by postulating a whole bunch of “successor subjects” to epistemology, economists may need to be careful in clinging to “our utilitarian essence” in trying to relegate the “foundation” of the social sciences to other realms.

Part II: Utility Theory to Hermeneutics

It is striking that many of the philosophers that the economists who are trying to figure out where to go in the neoclassical and Austrian traditions are appealing to the same philosophers Rorty did. Lavoie (1990) appealed to Heiddeger and Gadamer under Rorty’s influence to rid economics of its foundationalism in the way I described. Boettke is appealing to Quine and Dewey, two pragmatists to understand Mises’ apriori assumption of rationality over human action. Rizzo is appealing to Wittgenstein, one of Rorty’s “heroes” of Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature for his philosophy of language. Robb is appealing to Neitzsche, another one of Rorty’s major influences. Rorty is in some sense what got Lavoie going in the Hermaneutic research program to begin with. Perhaps, a return more specifically to the manner in which Rorty presented hermeneutics is what is necessary for economists to approach the question of rationality at this point, this section aims to more narrowly analyze Rorty’s hermeneutics, a concluding section suggests general lessons from the history of rationality out of a Rortian Hermeneutic research program in the subject of economic rationality.

Kuhn, Rorty, and Incommensurability

In chapter seven of Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature, Rorty appeals most fully to Thomas Kuhn’s philosophy of science. Kuhn’s philosophy of science includes the idea of “paradigms” in research, that is basic fundamental assumptions that go into a scientist’s work. Khun then carefully distinguishes between “commensurable paradigms,” those fundamental assumptions that can work together, and “incommensurable paradigms,” those fundamental assumptions that cannot. If there are two incommensurable paradigms at once, there will be a “paradigm shift.” The most famous and widely cited example is the shift from Newtonian physics to Quantum Mechanics in physics.

Rorty posits the new place of philosophy should be to “edify,” to be therapeutic in some sense on the personal level of the philosopher. To some extent, that idea of an “edifying philosophy” seems to be going on in the back of Robb’s mind in his response to Heckman on Nietzsche. But not only is philosophy to edify, it is also possible to use philosophy as hermeneutics to commensurate seemingly incommensurable paradigms. It may be the case that this is the direction economics in which must go.

In Vernon Smith’s Nobel Prize lecture (2002), he laid out a way in which paradigms could be thought to relate to each other in this question of rationality in economics. Smith distinguishes between “constructivist rationality,” drawing off Hayek’s program mentioned at the outset of this paper in The Counterrevolution of Science, and “ecological rationality.” “Constructivist rationality,” to Smith, is rationality stems from Cartesian rationalism (506) and “provisionally assumes or ‘requires’ agents to possess complete payoff and other information—far more than could ever be given to one mind.” Ecological rationality, on the other hand, is rationality that is identified with Hayek and the Scottish enlightenment. It is a “concept of rational order, as an undersigned ecological system that emerges out of cultural and biological evolutionary process” (508).

Vernon Smith thought that the research paradigms between the two are somehow commensurable. Though this is likely the case, most economists researching the literature in the behavioral and neoclassical traditions seem to disagree. Most of the economists in the hermeneutic tradition researching the issue seem to have Lakatos’ philosophy of science more prominent in their minds than Kuhn’s (Cachanosky 2013). Perhaps, for the moment, economics is in a place that is closer to Kuhn’s philosophy of science than Lakatos, and we need to assume that the paradigms between “ecological rationality” and “constructivist rationality” are incommensurable in some sense, though agree with Vernon Smith that they need not be. Further research in the Rortian hermeneutic tradition may help commensurate those paradigms.

Conclusion: Open-Mindedness in Rational Economic Discourse

Often, debate over rationality gets extremely heated thanks to its connection at times to politics and the nature of capitalism. For an example, in Nudge Thaler and Sunstein primarily place blame for the financial crisis on behavioral factors (2009 255-260). New Keynsians might respond to this by yelling at the top of their lungs that they’re ignoring aggregate demand, Austrians might respond by yelling at the top of their lungs that they’re ignoring the interest rate and business cycle theory. But perhaps a combination of the three, a pluralism, is necessary for the explanation. The problem with economic debates is too often when it gets associated with the political spheres, the arguments get personally provocative and nasty. This is how incommensurable paradigms occur, and that is likely what has occurred with the debate about rationality. Thaler and Sunstein are probably oversimplifying the complex myriad of institutional factors that went into causing the recession, but yelling that your business cycle theory explains it is not the right solution.

Zouboulakis ends Verities of Economic Rationality by proclaiming “What is Rational after all?” Rorty would say something like, ‘Rationality is not a human faculty, it’s a social virtue.’ In order to maintain open-minded discussion and approach a point when there can be normal discourse in the economics profession, perhaps this is the answer that is needed. Perhaps all the actors in a market economy are the “rational” ones in Rorty’s use of the term, and economists are not.

References:

Allen, R.G.D., and J.R. Hicks. 1934. “A Reconsideration of the Theory of Value.” Economica 1(1) (Feb. 1934): 52-76.

Arrow, Kenneth J. 1959. “Rational Choice Functions and Orderings.” Economica 24(102) (May): 121-27.

Boettke, Peter and Peter Leeson. 2006 “Was Mises Right?” Review of Social Economy 64(2). (June): 247-265.

Boettke, Peter J., Don Lavoie, and Virgil Henry Storr. 2004. “The Subjectivist Methodology of Austrian Economics and Dewey’s Theory of Inquiry.” Pp. 327–56 in Dewey, Pragmatism, and Economic Methodology, ed. Elias

L. Khalil. London: Routledge.

Edgeworth, Francis. “Mathematical Physics.” 2013. In The History of Economic Thought: A Reader edited by Steven G. Medema and Warren J. Samuels. New York, NY: Routledge. (Originally published 1881).

Hammond, Peter J. 1997. “Rationality in Economics.” Unpublished. http://web.stanford.edu/~hammond/ratEcon.pdf.

Hayek, Friedrich. 1952. The Counterrevolution in Science. Indianapolis, Indiana: The Free Press.

Jevons, William S. “The Theory of Political Economy.” 2013. In The History of Economic Thought: A Reader edited by Steven G. Medema and Warren J. Samuels. New York, NY: Routledge. (Originally published in 1871).

Kahneman, Daniel. 2003. “Maps of Bounded Rationality: Psychology for Behavioral Economics.” American Economic Review 93 (December): 1449-75.

Lavoie, Donald. 190. “Economics and Hermeneutics.” In Economics and Hermeneutics ed. by Don Lavoie. Abidingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

—. 2011. Thinking Fast and Slow. New York, NY: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

McKenzie, Robert B. 2009. “Rationality in Economic thought: From Thomas Robert Malthus to Alfred Marshall and Philip Wicksteed.” In Predictably Rational, edited by Robert McKenzie. Berlin Heidelberg: Springer. http://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007%2F978-3-642-01586-1_4?LI=true.

Menger, Carl. 1976. Principles of Economics. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute. http://mises.org/sites/default/files/Principles%20of%20Economics_5.pdf. (Originally Published in 1871.)

Mises, Ludwig. 1998. Human Action. Auburn, AL: Ludwig von Mises Institute. (Originally published in 1949).

—. 2013. Epistemological Problems in Economics. Indianapolis: Liberty Fund, Inc. http://oll.libertyfund.org/titles/2427. (Originally published in 1933).

Read, Daniel. 2004. “Utility theory from Jeremy Bentham to Daniel Kahneman.” LSE Department of Operational Research Working Paper LSEOR 04-64.

Rizzo, Mario. 2012. “The Problem of Rationality: Behavioral Economics Meets Austrian Economics.” Unpublished. http://econ.as.nyu.edu/docs/IO/28036/BEHAVIORAL_ECONOMICS.pdf.

Robb, Richard. 2009. “Nietzsche and the Economics of Becoming.” Capitalism and Society. 4(3) (January). < http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2209313>

Robbins, Lionel. An Essay on the Nature and Significance of Economic Science.

Rorty, Richard. 1979. Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Samuelson, Peter. 1938. “A Note on the Pure Theory of Consumer’s Behaviour.” Economica, New Series, 5(17) (February): 61-71.

Thaler, Richard and Cass Sunstein. 2009. Nudge. Penguin Books.

Simon, Herbert A. 1972. “Theories of Bounded Rationality.” In Decision and Organization edited by C.B. McGuire and Roy Radner. Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing. http://mx.nthu.edu.tw/~cshwang/teaching-economics/econ5005/Papers/Simon-H=Theoriesof%20Bounded%20Rationality.pdf.

—. 1978. “Rational Decision-Making in Business Organizations.” Paper Presented at Nobel Prize Memorial Lecture Pittsburg, PA.

Zouboulakis, Michel. 2013. The Varieties of Economic Rationality. New York, NY: Routledge.

[1] Though Mises’ 1949 work Human Action is cited here, it is important to note that he had laid out very similar positions much earlier (1933/2013).

The Cruel, Conceited Follies of Trump’s Foreign Policy: 2026 Edition

Trump has now taken extralegal military action in Venezuela. Trump is strongly considering such action in Iran. And Trump keeps flirting with aggressive globally destabilizing military annexation of Greenland, a NATO ally. Many people are acting perplexed. After all, didn’t libertarian “genius” and totally-not-delusional-reactionary Walter Block tell us back in 2016 that libertarians should vote for Trump because he is anti-war? After this proved to be false the first term, didn’t totally-not-delusional-reactionary Walter Block then tell us again case for libertarianism was that he was anti-war and anti-foreign intervention, and that he was super cereal this time?

Sarcasm aside, I think it is worth revisiting why Trump’s foreign policy turn towards a radical sort of imperialist interventionism is so evil and unsurprising. I was confident back in 2016 that he was always going to be an old-school imperialist who uses US military conquest purely for resource extraction in a way that would be far worse than neocon warmongering. I wrote at the time, following Zach Beauchamp (who continues to emphasize this point), that Trump’s foreign policy was neither the neo-conservative interventionism of the Clintons and Bushes of the world, nor the principled anti-interventionism of libertarian scholars like Christopher Coyne and Abigail Hall, nor even the nationalist isolationism of paleoconservatives like James Buchanan. Instead, Trump’s foreign policy has always (quite consistently, since he was still a pro-choice democrat in the 90s) been about advancing inchoate national economic and political interests—which really just means the interests of the politically connected.

This connection between Trump’s completely crankish economic nationalism and his imperialist foreign policy is even tighter now than it was then. It seems Trump is likely facing a rejection of his unconstitutional overreach of unilaterally applying economically suicidal tariffs from SCOTUS. The tariffs, which originally, might I add, were based on perhaps the single dumbest attempt to do economics I have ever seen, appeared to be lifted straight from ChatGPT, given that his main economic advisor on these matters, Peter Navarro, is literally a fraudster. As a result, he now seems to be manufacturing a national security crisis so he can impose tariffs without congress’ blessing.

But I do not want to revisit Trump’s imperialist foreign policy just to gloat. I also want to revisit and restate why this foreign policy is unbelievably unjust and self-destructive. What I wrote back in 2016 is still worth reposting at length:

First, Trump’s style of Jacksonian foreign policy is largely responsible for most of the humanitarian atrocities committed by the American government. Second, Trump’s economic foreign policy is antithetical to the entire spirit of the liberal tradition; it undermines the dignity and freedom of the individual and instead treats the highest good as for the all-powerful nation-state (meaning mostly the politicians and their special interests) as the end of foreign policy, rather than peace and liberty. Finally, Trump’s foreign policy fails for the same reasons that socialism fails. If the goals of foreign policy are to represent “national interest,” then the policymaker must know what that “national interest” even is and we have little reason to think that is the case, akin to the knowledge problem in economic coordination.

… This is because the Jacksonian view dictates that we should use full force in war to advance our interests and the reasons for waging war are for selfish rather than humanitarian purposes. We have good reason to think human rights under Trump will be abused to an alarming degree, as his comments that we should “bomb the hell out of” Syria, kill the noncombatant families of suspected terrorists, and torture detainees indicate. Trump is literally calling for the US to commit inhumane war crimes in the campaign, it is daunting to think just how dark his foreign policy could get in practice.

To reiterate: Trump’s foreign policy views are just a particularly nasty version of imperialism and colonialism. Mises dedicated two entire sections of his chapter on foreign policy in Liberalism: The Classical Tradition to critiquing colonialism and revealing just how contrary these views are to liberalism’s commitment to peace and liberty. In direct opposition to Trump’s assertions that we should go to war to gain another country’s wealth and resources and that we should expand military spending greatly, Mises argues:

“Wealth cannot be won by the annexation of new provinces since the “revenue” deprived from a territory must be used to defray the necessary costs of its administration. For a liberal state, which entertains no aggressive plans, a strengthening of its military power is unimportant.”

Mises’ comments on the colonial policy in his time are extremely pertinent considering Trump’s calls to wage ruthlessly violent wars and commit humanitarian crises. “No chapter of history is steeped further in blood than the history of colonialism,” Mises argued. “Blood was shed uselessly and senselessly. Flourishing lands were laid waste; whole peoples destroyed and exterminated. All this can in no way be extenuated or justified.”

Trump says the ends of foreign policy are to aggressively promote “our” national interests, Mises says “[t]he goal of the domestic policy of liberalism is the same as that of its foreign policy: peace.” Trump views the world as nations competing in a zero-sum game and there must be one winner that can only be brought about through military conquest and economic protectionism, Mises says liberalism “aims at the peaceful cooperation between nations as within each nation” and specifically attacks “chauvinistic nationalists” who “maintain that irreconcilable conflicts of interest exist among the various nations[.]” Trump is rabidly opposed to free trade and is horrifically xenophobic on immigration, the cornerstone of Mises’ foreign policy is free movement of capital and labor over borders. There is no “congruence” between Trump and any classically liberal view on foreign policy matters in any sense; to argue otherwise is to argue from a position of ignorance, delusion, or to abandon the very spirit of classical liberalism in the first place.

…Additionally, even if we take Trump’s nationalist ends as given, the policy means Trump prefers of violent military intervention likely will not be successful for similar reasons to why socialism fails. Christopher Coyne has argued convincingly that many foreign interventions in general fail for very similar reasons to why attempts at economic intervention fail, complications pertaining to the Hayekian knowledge problem. How can a government ill-equipped to solve the economic problems of domestic policy design and control the political institutions and culture of nations abroad? Coyne mainly has the interventionism of neoconservatives and liberals in mind, but many of his insights apply just as well to Trump’s Jacksonian vision for foreign policy.

The knowledge problem also applies on another level to Trump’s brand of interventionism. Trump assumes that he, in all his wisdom as president, can know what the “national interest” of the American people actually is, just like socialist central planners assume they know the underlying value scales or utility functions of consumers in society. We have little reason to assume this is the case.

Let’s take a more concrete example: Trump seems to think one example of intervention in the name of national interest is to take the resource of another country that our country needs, most commonly oil. However, how is he supposed to know which resources need to be pillaged for the national interest? There’s a fundamental calculation problem here. A government acting without a profit signal cannot know the answer to such a problem and lacks the incentive to properly answer it in the first place as the consequences failure falls upon the taxpayers, not the policy makers. Even if Trump and his advisors could figure out that the US needs a resource, like oil, and successfully loots it from another country, like Libya, there is always the possibility that this artificial influx of resources, this crony capitalist welfare for one resource at the expense of others, is crowding out potentially more efficient substitutes.

For an example, if the government through foreign policy expands the supply of oil, this may stifle entrepreneurial innovations for potentially more efficient resources in certain applications, such as natural gas, solar, wind, or nuclear in energy, for the same reasons artificially subsidizing these industries domestically stifle innovation. They artificially reduce the relative scarcity of the favored resource, reducing the incentive for entrepreneurs to find innovative means of using other resources or more efficient production methods. At the very least, Trump and his advisors would have little clue how to judge the opportunity cost of pillaging various resources and so would not know how much oil to steal from Libya. Even ignoring all those problems, it’s very probable that it would be cheaper and morally superior to simply peaceably trade with another country for oil (or any other resource) rather than waging a costly, violent, inhumane war in the first place.

Having said all that, there is plenty I got wrong in picturing Trump as an old-school imperialist. During Trump’s first term, I underestimated the extent to which institutional constraints would stop him from acting on his worst nationalist and imperialist impulses. But this term, those constraints are gone. The Mattises, Tillersons, Boltons, and Pences of the world have been replaced with the Vances, Noems, Rubios, and Hegseths. As a result, thinking of Trump as an old-school imperialist and nationalist is becoming more accurate since he is allowed to act on his irrational, deranged impulses.

Second, I failed to distinguish sufficiently between resource extraction through indirect means of violent regime change, tariffs, weapons supply, and 19th-century colonialist-style direct annexation versions of it. I do still think that if Trump really did what he most consistently wants he would do quite a bit of annexation and old school colonialism (see his comments on Greenland and Canada), but he seems a bit more content than I projected back then to use military force to install stooges and puppet regimes for resource extraction (as he has sought to do in both Gaza and now Venezuela). Which, to your point, is not as different from the Nixon/Bush/Clinton/Reagan type intervention as reactionary centrists would have you believe, but the nakedness of the extractive nationalist motivation does mark a difference that encourages even more brazenly cruel, more illegal, and more strategically incoherent and unpredictable interventionist warmongering.

Thirdly, and most obviously, I greatly overestimated his coherence on foreign policy. Whether it is him handicapping US influence in the Pacific by withdrawing from the TPP while implementing tariffs on Chinese goods to seem tough in the first term, which just gave China more leverage in the region. Or whether it’s his delusional flip-flopping on Russia and Ukraine based on who he talked to last, constantly this term. Or whether it’shis random provocation against Iran in 2019 by killing one of their generals. Or whether it’s his insane flip-flopping between Nuclear War talk and sychophancy with North Korea. Or the total randomness of his attacking Venezuela for more domestic than foreign policy reasons now. He is simply far more impulsive and deranged than I would have predicted in 2016. This part of that old article seems especially stale now:

After all, it doesn’t matter so much the character of public officials as the institutional incentives they face. But in matters of foreign policy problems of temperament and character do matter because the social situation between foreign leaders in diplomacy can often make a huge difference.

I did hedge that by allowing that Trump may be a uniquely unfit person so as to constitute a sui-generis case. But I should have been more emphatic about that: Trump really is a uniquely world-historically dangerous monster, and he has gotten more and more incoherent and impulsive over the years with his cognitive decline.

Finally, the biggest miss in my analysis of Trump’s foreign policy back then is that I put far too much emphasis on Trump’s focus on material goods, thinking he really just thought of geopolitics like a 12-year-old approaches a turn-based strategy game like Risk in just accruing more stuff. But in reality, his approach is far more disturbing and vile than even that. It is not simply about getting oil for US oil companies. In the case of Venezuela, oil execs do not seem so gun-ho. As one private equity investor told the Financial Times last week, “No one wants to go in there when a random fucking tweet can change the entire foreign policy of the country.” Indeed, the political risk is so big there Exonn’s CEO has called Venezuela “uninvestable” and Trump is trying to force oil companies to misallocate capital to Venezuela.

Narrow left-wing materialists’ critiques like mine misfire because they treat material resources as the main thing. It is not the oil per se that Trump wants, but what the oil represents. He is instead approaching international geo-politics like an 8-year-old driven by malignant narcissism: he wants symbols of nationalist masculine domination. Indeed, when asked why he wanted Greenland, Trump was quoted as saying:

Because that’s what I feel is psychologically needed for success. I think that ownership gives you a thing that you can’t do, whether you’re talking about a lease or a treaty. Ownership gives you things and elements that you can’t get from just signing a document.

Indeed, the fact that Greenland looks big on a Mercator projection of the earth has as much to do with why Trump wants it as the oil. As Trump continues his authoritarian assaults on individual liberty domestically and pursues semiotic nationalist domination internationally, one can only vainly pray that something keeps his dark, demonic, twisted sadist fantasies in check without devolving into a true civilization-level threat.

“Towards a Complete Libertarianism”

from Kevin Vallier, in the latest issue of Isonomia Quarterly.

Don’t forget to check out the rest, which includes essays on Hayek, the geopolitics of Greenland, the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki, and a poem by Robert Frost.

What I’ve been working on

Hi all,

Apologies for not blogging very much. Here’s what I’ve been working on. There is more to come!

New issue of Isonomia Quarterly is out!

Get your fix right here!

Notes On Liberty is Now On Bluesky

For those of you on Bluesky, we now are too. Feel free to give us a follow.

In the Ruins of Public Reason, Part III: When the Barbarians Are at the Gates; Fascism, Bullshit, and the Paradox of Tolerance

Note: This is the third in a series of essays on public discourse. Here’s Part 1 and Part 2

Three years ago, I started this essay series on the collapse of public discourse. At the time, I was frustrated by how left-wing and progressive spaces had become cognitively rigid, hostile, and uncharitable to any and all challenges to their orthodoxy. I still stand by most everything I said in those essays. Once you have successfully identified that your interlocutors are genuinely engaging in good faith, you must drop the soldier mindset that you are combating a barbarian who is going to destroy society and adopt a scout mindset. For discourse to serve any useful epistemic or political function, interlocutors must accept and practice something like Habermas’ rules of discourse or Grice’s maxims of discourse, where everyone is allowed to question or introduce any idea to cooperatively arrive at an intersubjective truth. The project of that previous essay was to therapeutically remind myself and any readers to actually apply and practice those rules of discourse in good-faith communication.

However, at the time, I should have more richly emphasized something that has been quite obviously true for some time now: most interlocutors in the political realm have little to no interest in discourse. I wish more people had such an interest, and still stand by the project of trying to get more people, particularly in leftist and libertarian spaces, to realize that when they speak to each other, they are not dealing with barbarian threats. However, recent events have made it clear that the real problem is figuring out when an interlocutor is worthy of having the rules of discourse applied in exchanges with them. Here is an obviously non-exhaustive list of such events in recent times that make this clear:

- The extent to which Trump himself, as well as his advisors and lawyers, engage in lazy, dishonest, and bad-faith rationalizations for naked, sadistic, unconstitutional executive power grabs.

- The takeover of the most politically influential social media by a fascist billionaire rent-seeker has resulted in a complete fragmentation and breakdown of the online public square.

- The degree to which most on the right and many on the left indulge in insane conspiracy theories, which have eroded and destroyed the epistemic norms of society, for reasons of rational irrationality.

- Even the Supreme Court, the institution that ostensibly is most committed to publicly justifying and engaging in good-faith reasoning about laws, is now giving blatantly awful, authoritarian opinions so out of step with their ostensibly originalist and/or textualist legal hermeneutics and constitutionalist principles (not to mention the opinions of even conservative judges in lower courts). It certainly seems the justices are just as nakedly corrupt and intellectually bankrupt as rabble-rousing aspiring autocrats. Indeed, the court is in such a decrepit state of personalist capture by an aspiring fascist dictator that they aren’t even attempting to publicly justify ‘shadow docket’ rulings in his favor. One can only conclude conservative justices are engaging in bad-faith power-grabs for themselves, whether they intend to or not. Although this has always been true of statist monocentric courts to some extent, recent events have only further eroded the court’s pretenses to being a politically

All these were obvious trends three years ago and have very predictably only gotten more severe. You may quibble with the extent of my assessment of any individual example above. Regardless, all but the most committed of Trumpanzees can agree that there is a time and place to become a bit dialogically illiberal in times like these. Thus, it is time to address how one can be a dialogical liberal when the barbarians truly are at the gates. The tough question to address now is this: what should the dialogical liberal do when faced with a real barbarian, and how does she know she is dealing with a barbarian?

This is an essay about how to remain a dialogical liberal when dialogical liberalism is being weaponized against you. This essay isn’t for the zealots or the trolls. It’s for those of us who believed, maybe still believe, that democracy depends on dialogue—but who are also haunted by the sense that this faith is being used against us.

Epistemically Exploitative Bullshit

I always intended to write an essay to correct the shortcomings of the original one. I regret that, for various personal reasons, I did not do so sooner. The sad truth is that a great many dialogical illiberals who are also substantively illiberal engage in esoteric communication (consciously or not). That is, their exoteric pretenses to civil, good-faith communication elide an esoteric will to domination. Sartre observed this phenomenon in the context of antisemitism, and he is worth quoting at length:

Never believe that anti‐Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti‐Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert. If you press them too closely, they will abruptly fall silent, loftily indicating by some phrase that the time for argument is past. It is not that they are afraid of being convinced. They fear only to appear ridiculous or to prejudice by their embarrassment their hope of winning over some third person to their side.

If then, as we have been able to observe, the anti‐Semite is impervious to reason and to experience, it is not because his conviction is strong. Rather, his conviction is strong because he has chosen first of all to be impervious.

What Sartre says of antisemitism is true of illiberal authoritarians quite generally. Thomas Szanto has helpfully called this phenomenon “epistemically exploitative bullshit.”

One feature of epistemically exploitative bullshit that Szanto highlights is that epistemically exploitative bullshit need not be intentional. Indeed, as Sartre implies in the quote above, the ‘bad faith’ of the epistemically exploitative bullshitter involves a sort of self-deception that he may not even be consciously aware of. Indeed, most authoritarians (especially in the Trump era) are not sufficiently self-aware or intelligent enough to consciously realize that they are deceiving others about their attitude towards truth by spouting bullshit. As Henry Frankfurt observed, bullshit is different from lying in that the liar is intentionally misrepresenting the truth, but the bullshitter has no real concern for truth in the first place. Thus, many bullshiters (especially those engaged in epistemically exploitative bullshit) believe their own bullshit, often to their detriment.

However, the fact that epistemically exploitative bullshit is often unintentional, or at least not consciously intentional, creates a serious ineliminable epistemic problem for the dialogical liberal who seeks to combat it. It is quite difficult to publicly and demonstrably falsify the hypothesis that one’s interlocutor is engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit. This often causes people who, in their heart of hearts, aspire to be epistemically virtuous dialogical liberals to misidentify their interlocutors as engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit and contemptuously dismiss them. I, for one, have been guilty of this quite a bit in recent years, and I imagine any self-reflective reader will realize they have made this mistake as well. We will return to this epistemic difficulty in the next essay in this series.

To avoid this mistake, we must continually remind ourselves that the ascription of intention is sometimes a red herring. Epistemically exploitative bullshit is not just a problem because bullshitters intentionally weaponize it to destroy liberal democracies. It is a problem because of the social and (un)dialectical function that it plays in discourse rather than its psychological status as intentional or unintentional.

It is also worth remembering at this point that it is not just fire-breathing fascists who engage in epistemically exploitative bullshit. Many non-self-aware, not consciously political, perhaps even liberal, political actors spout epistemically exploitative bullshit as well. Consider the phenomenon of property owners—both wealthy landlords and middle-class suburbanites—who appeal to “neighborhood character” and environmental concerns to weaponize government policy for the end of protecting the economic rents they receive in the form of property values. Consider the similar phenomenon of many market incumbents, from tech CEOs in AI to healthcare executives and professionals, to sports team owners, to industrial unions, to large media companies, who all weaponize various seemingly plausible (and sometimes substantively true) economic arguments to capture the state’s regulatory apparatus. Consider how sugar, tobacco, and petrochemical companies all weaponized junk science on, respectively, obesity, cigarettes, and climate change to undermine efforts to curtail their economic activity. Almost none of these people are fire-breathing fascists, and many may believe their ideological bullshit is true and tell themselves they are helping the world by advancing their arguments.

The pervasive economic phenomenon of “bootleggers and Baptists” should remind us that an unintentional form of epistemically exploitative bullshit plays a crucial role in rent seeking all across the political spectrum. This form of bullshit is particularly hard to combat precisely because it is unintentional, but its lack of intentionality in no way lessens the harmful social and (un)dialectical functions it severe.

Despite those considerations, it is still worth distinguishing between consciously intentional forms of aggressive esotericism and more unintentional versions because they must be approached very differently. Unintentional bullshitters do not see themselves as dialogically illiberal. Therefore, responding to them with aggressive rhetorical flourishes that treat them contemptuously is very unlikely to be helpful. For this reason, the general (though defeasible) presumption that any given person spouting epistemically exploitative bullshit is not an enemy that I was trying to cultivate in the second part of this essay series still stands. In the next essay, I will address how we know when this presumption has been defeated. However, for now, let us turn our attention to the forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit common today on the right. We have now seen how epistemically exploitative bullshit can appear even in technocratic, liberal settings. But that phenomenon takes on a more virulent form when fused with authoritarian intent. This is what I call aggressive esotericism.

Aggressive Esotericism

The corrosiveness of these more ‘liberal’ and technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit discussed above, while serious, pales in comparison to more bombastically authoritarian forms of it. The truly authoritarian epistemically exploitative bullshiter aims at more than amassing wealth by capturing some limited area of state policy. While he also does that, the fascist aims at the more ambitious goal of dismantling democracy and seizing the entire apparatus of the state itself.

Let us name this more dangerous form of epistemically exploitative bullshit. Let us call this aggressive esotericism and loosely define it as the phenomenon of authoritarians weaponizing the superficial trappings of democratic conversation to elide their will to dominate others. This makes the fascistic, aggressive esotericist all the more cruel, destructive, and corrosive of society’s epistemic and political institutions.

It is worth briefly commenting on my choice of the words “aggressive esotericism” for this. The word “esoteric” in the way I am using it has its roots in Straussian scholars who argue that many philosophers in the Western tradition historically did not literally mean what their discursive prose appears to say. Esoteric here does not mean “strange,” but something closer to “hidden,” in contrast to the exoteric, surface-level meaning of the text. We need not concern ourselves with the fascinating and controversial question of whether Straussians are right to esoterically read the history of Western philosophy as they do. Instead, I am applying the general idea of a distinction between the surface level and deeper meaning of a text, the sociological problem of interpreting both the words and the deeds of certain very authoritarian political actors.

I choose the word “aggressive” to contrast with what Arthur Melzer calls “protective,” “pedagogical,” or “defensive” esotericism. In Philosophy Between the Lines Melzer argues that historically, philosophers often hid a deeper layer of meaning in their great texts. In the ancient world, Melzer argues, this was in part because they feared theoretical philosophical ideas could disintegrate social order (hence the “protective esotericism”), wanted their young students to learn how to come to philosophical truths themselves (hence the “pedagogical esotericism”), or else wanted to protect themselves from authorities for ‘corrupting the youth’ (as Socrates was accused) with their heterodox ideas.

As the modern world emerged during the Enlightenment, Melzer argues esotericism continued as philosophers such as John Locke wrote hidden messages not just for defensive reasons but to help foster liberating moral progress in society, as they had a far less pessimistic view about the role of theoretical philosophy in public life (hence their “political esotericism”). Whether Melzer is correct in his reading of the history of Western political thought need not concern us now. My claim is that many authoritarians (both right-wing Fascists and left-wing authoritarian Communists) invert this liberal Enlightenment political esotericism by engaging—both in words and in deeds, both consciously and subconsciously, and both intentionally and unintentionally—in aggressive esotericism. Hiding their esoteric will to domination behind a superficial façade of ‘rational’ argumentation.

Aggressive esotericism is a subset of the epistemically exploitative bullshit. While aggressive esotericism may be more often intentional than more technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit, it is not always so. You might realize this when you reflect on heated debates you may have had during Thanksgiving dinners with your committed Trumpist family members. Nonetheless, this lack of intention doesn’t cover up the fact that their wanton wallowing in motivated reasoning, rational ignorance, and rational irrationality has the selfish effect of empowering members of their ingroup over members of their outgroup. This directly parallels how the lack of self-awareness of the technocratic rentseeker ameliorates the dispersed economic costs on society.

Aggressive Esotericism and the Paradox of Tolerance

Even if one suspects one is encountering a true fascist, one should still have the defeasible presumption that they are a good-faith interlocutor. Nonetheless, fascists perniciously abuse this meta-discursive norm. This effect has been well-known since Popper labelled it the paradox of tolerance.

The paradox of tolerance has long been abused by dialogical illiberals on both the left and the right to undermine the ideas of free speech and toleration in an open society, legal and social norms like academic freedom and free speech, and to generally weaken the presumption of good faith we have been discussing. This, however, was far from Popper’s intention. It is worth revisiting Popper’s discussion of the Paradox of Tolerance in The Open Society and Its Enemies:

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right even to suppress them, for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to anything as deceptive as rational argument, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, exactly as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or as we should consider incitement to the revival of the slave trade.

His point here is not so much to sanction State censorship of fascist ideas. Instead, his point is that there are limits to what should be tolerated. To translate this to our language earlier in the essay, he is just making the banal point that our presumption of good-faith discourse is, in fact, defeasible. The “right to tolerate the intolerant” need not manifest as legal restrictions on speech or the abandonment of norms like academic freedom. This is often a bad idea, given that state and administrative censorship creates a sort of Streisand effect that fascists can exploit by whining, “Help, help, I’m being repressed.” If you gun down the fascist messenger, you guarantee that he will be made into a saint. Further, censorship will just create a backlash as those who are not yet fully-committed Machiavellian fascists become tribally polarized against the ideas of liberal democracy. Even if Popper himself might not have been as resistant to state power as I am, there are good reasons not to use state power.

Instead, our “right to tolerate the intolerant” could be realized by fostering a strong, stigmergically evolved social stigma against fascist views. Rather than censorship, this stigma should be exercised by legally tolerating the fascists who spout their aggressively esoteric bullshit even while we strongly rebuke them. Cultivating this stigma includes not just strongly rebuking the epistemically exploitative bullshit ‘arguments’ fascists make, but exercising one’s own right to free speech and free association, reporting/exposing/boycotting those, and sentimental education with those the fascists are trying to target. Sometimes, it must include defensive violence against fascists when their epistemically exploitative bullshit manifests not just in words, but acts of aggression against their enemies.

The paradox of tolerance, as Popper saw, is not a rejection of good-faith dialogue but a recognition of its vulnerability. The fascists’ most devastating move is not to shout down discourse but to simulate it: to adopt its procedural trappings while emptying it of sincerity. What I call aggressive esotericism names this phenomenon. It is the strategic abuse of our meta-discursive presumption of good faith.

Therefore, one must be very careful to guard against mission creep in pursuing this stigmergic process of cultivating stigma in defense of toleration. As Nietzsche warned, we must be guarded against the danger that we become the monsters against whom we are fighting. I hope to discuss later in this essay series how many on the left have become such monsters. For now, let us just observe that this sort of non-state-based intolerant defense of toleration does not conceptually conflict with the defeasible presumption of good faith.

In the next part of this series, I turn to the harder question: when and how can a dialogical liberal justifiably conclude that an interlocutor is no longer operating in good faith?

New issue of Isonomia Quarterly is out

You can read the whole thing here.

New issue of Isonomia Quarterly is out

You can read the whole thing here.

New issue of Isonomia Quarterly is out

You can read the whole thing here.

Some arbitrage free Byzantine rates of return

Byzantium. The surprising life of a medieval empire – by Judith Herrin

In the economy chapter, apart from the often overlooked hard-ass (gold) and long-ass (700 years) of monetary stability, the author discusses some social aspects of economic life. The Byzantine elites, following on Ancient Rome’s disdain for commercial endeavors, typically opted to invest in three things: Land, administrative offices (which could confer some coin in unofficial ways), and titles in the Court.

A Byzantine celebration, as copilot imagined it. In the other versions, people were so hardcore eastern orthodox christians that even had halos.

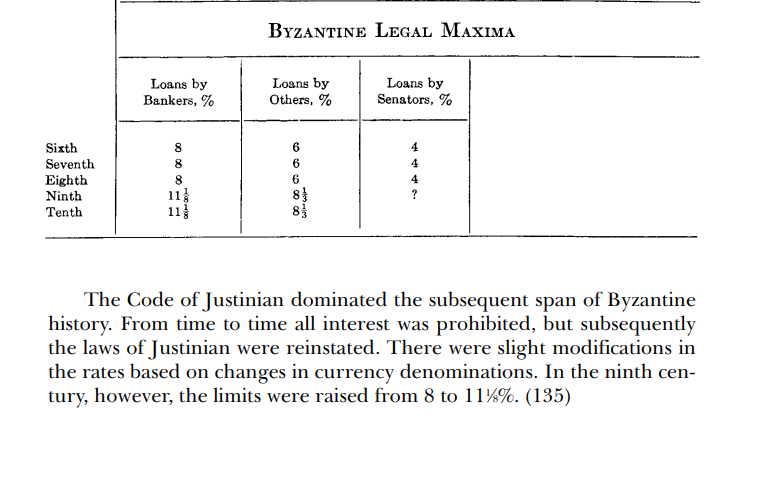

The Court titles had fancy names and came with regular allowances. The more mundane ones had a rate of return of 2.5%- 3.0%, while the higher-ups (like Protospatharios, loosely meaning First Sword Bearer, with responsibilities that oscillated among Chief Bodyguard, Receptionist and Master of Ceremonies) reached 8.3%. Since Byzantines had also inherited Rome’s practise of capping interest rates, we know that a simple citizen could lend at a rate of 6.0% (a banker at 8.0% and a distinguised person like a Senator at 4.0%).

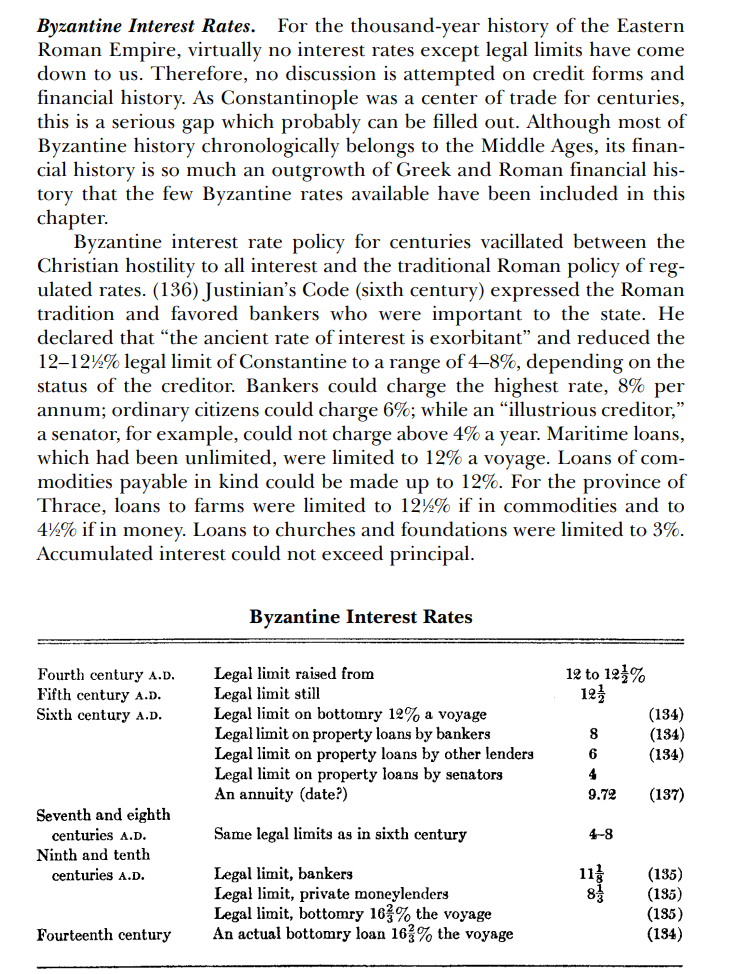

Re: Byzantine interest rates, from the impressive but rather dry, A History of Interest Rates – by Sidney Homer & Richard Sylla

So, it mostly did not make sense to buy a Court title, money-wise. Unless you did manage to land as the Protospatharios, so you could enter a risk-free carry trade of 2.3% and also enjoy lovely red robes with gold lining or white robes and a golden mantle (the latter attire was reserved for eunuchs). Half-joking aside, the titles were not transferable (that is, no secondary market), so you could not probably even get back the initial investment. It turns out, fancy names / clothes/ duties/ company were a major factor, after all. And secondary markets serve a purpose, at least sometimes.

Piece of music

A new bill, currently under public consultation, is poised to introduce quotas, yes, for music:

Greek-Language Music Quota Bill Sparks Controversy (BalkanInsight)

In its proposed form, the bill tinkers with the music lists aired in common areas (lobbies, elevators, corridors etc) of various premises (hotels, traveling facilities, casinos and shopping malls). The programs should consist of a minimum of 45% of either Greek-language songs, or instrumental versions of said songs. The quota leaves out cafes, restaurants and such (thus slinking away from a direct breach of private economic liberty, as interventions like anti-smoking laws in some cases were found as too heavy-handed). The bill also incentivises radio stations to scale up, so to say, the play-time of this kind of songs, by allocating them more advertising time (another thing that is also strictly regulated, obviously), if they comply to some percentage. Finally, there are some provisions regarding soundtracks in Greek movie productions.

There is an international angle in this protectionist instrument (pun intended). Wiki reveals that a handful of countries apply some form or another of music quotas, with France the most prominent among them. The Greek minister also mentioned Australia and Canada in an interview.