The pandemic, and the consequent decisions taken by our and other governments, have confronted us with the question of the extent of our autonomy. Although we are aware of the exceptional nature of the situation, the matter about the right that assists each individual to make decisions about their own life returns more strongly.

In this sense, we can wonder: How do we make decisions? Are we rational beings? Are thus our decision-making processes rational or we tend to act based on emotions, instincts, or heuristics? Even if we think in terms of choices rather than of actions, do we have enough evidence to think that we rationally choose between options? And if so, can we find the optimal solutions for our problems? Can we evaluate the optimality of our decisions?

The rationality of our actions and our decision-making processes have been widely discussed, not only in the field of economics but also in the legal, political, and sociological realms. Some authors have proposed that our decisions are not based on perfect information or precise though-processes, as Friedrich Hayek, who enlightened us about dispersed knowledge in society or Herbert Simon , who showed us how limited rationality works in real decision-making situations.

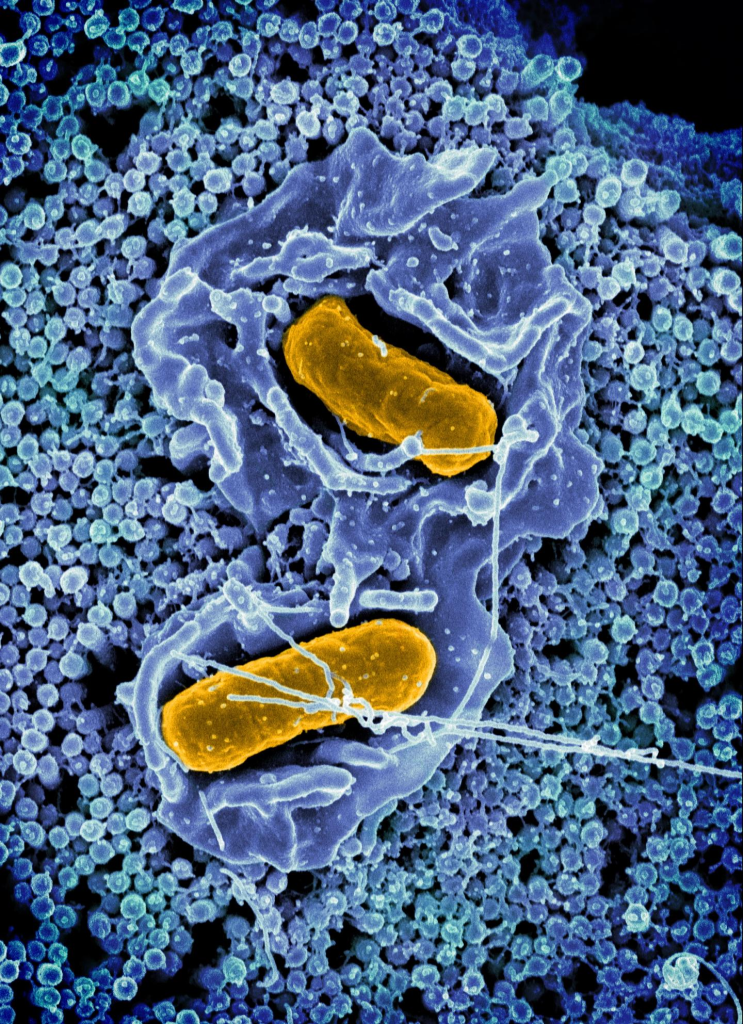

More recently, various theories such as behavioral economics and several experiments conducted by scholars from different disciplines, such as those conducted by Carl Sunstein, have showed that individuals act influenced by cognitive limitations and emotional biases. For example, some of these studies have shown how, influenced by these biases, we fail in our perception of the risk, miscalculating the odds we have of suffering certain diseases or how our choices are influenced by the way the relevant information is presented (framing). Thus, it has long been revealed that human actions and choices are not the result of a perfectly rational thought-process, and such discoveries were very useful in predicting certain patterns of behavior.

Personally, I have always found these theories fascinating, showing us that our mind does not work as the precise instrument that other visions have proposed. These “limitations” of our rationality and cognitive capacity have always led me to conclude that we must assume a humble position regarding what we can and cannot do in terms of public policies or the “construction” of social and political reality. Even this humility should be applied to scientific knowledge that manifests itself in constant change and revision. What is worrying is that, recently, this type of analysis has made a jump from the descriptive realm to the normative one, obtaining prescriptive conclusions from these experiments.

On the other hand, nowadays it is common to find that, from different perspectives and schools, subjective rights of all kinds are multiplied. It seems that individuals enjoy -at least theoretically- not only all the rights constitutionally recognized, the rights established by international human rights treatises and all the tacit or unwritten rights but also the collective rights (adding several generations). It is discussed from the right to elect and to be elected (i.e., lowering the age of vote) to the right to enjoy a healthy environment. In addition, from diverse political agendas, it is proposed the widening of all rights enjoyed by people, groups and even animals. We could discuss at length about these rights and obligations involving third parties – not only to respect them but also, in many cases, to take responsibility for the effective enjoyment of them.

But it would seem that, among all these rights that we enjoy or intend to enjoy, the right to be wrong does not appear. Everything is permitted (again, in theory) while individuals live according to the standards or goals to accepted by the community and the State at a given time. From different perspectives we are constantly offered advice and suggestions to achieve the ideal that is presented almost as indisputable: a long, healthy, and calm life (not without some ingredient of novelty or adventure). Not only from the philosophical and theological views -that indicate that human life seems to have happiness, virtue, personal flourishing, or any other transcendent purpose as its goal- but also from more scientific perspectives that provide us with details about what our limitations are in making the right decisions about how to lead a full life. They all seem to agree in proposing a “perfectionist” ideal of human life.

However, when combined these two tendencies of thought -that is, on the one hand, the perfectionist ideal of human life and, secondly, a clear vision about human limitations for making good decisions or planning courses of action, it appears this idea that it is necessary to “underpin”, help or direct the decisions of individuals with the intention to help them that they achieve such ideal ends.

Just to illustrate this point outside the case of the pandemic, we note that all political views coincide in “guiding” citizens when it comes to eating and healthy habits. In this regard, if directing citizens consumption is concerned, much of the political range (conservatism, social democracy, and even the left) seem to agree in wanting to provide healthy standards that everyone should enjoy. This is reflected in a variety of decisions made by governments from one “ideal individual” – which range from prohibiting table salt in restaurants, forcing stores to not sell alcohol at a certain time of the night (and not only limiting the sale to adults as might be expected), forcing food producers or distributors to include a lot of information about its components in packaging, etc. The question does not end here: smoking tobacco, for example, has been almost completely banned everywhere (and not only in closed public spaces but also in open spaces and even in many buildings or premises for exclusive private use).

Faced with this reality, we ask ourselves the question: Do we have the right or not to decide about our lives (our body, our health, etc.)? Can adults without serious cognitive problems -beyond those biases named above that we all “suffered”- with their legitimate autonomy, freedom, and responsibility and, if you like, access to public information about the possible consequences of their actions, choose to assume risks? Do them have the right to put salt to their food, although there are numerous studies that show a correlation between salt intake and high blood pressure? Don’t all those who choose to paraglide or drive a car on a high-speed avenue also take risks? Why are some elections forbidden or more “observed” than others?

So, from this perspective that combines perfectionism and observation of the cognitive limitations of individuals: Does this lead us directly to conclude that our decisions should be replaced or at least “influenced” or “improved” – as suggested by the nudge theory – by the decision of a public official or an expert scientist? Do we let a nutritionist tell us the ideal diet based on recent generic scientific studies? Do we allow an official or civil servant to indicate what activity / sport / food / drink / medical treatment / insurance should we carry out / practice / consume / submit to / hire considering the general statistics of the population for my age / sex / social condition? Would we allow this civil servant to “suggest” us the way of interacting with other individuals or habits to adopt?

To answer this question, it could help us to bring here the conceptual distinction proposed by Dr. Martín Diego Farrell in his essay on “Nino, democracy and utilitarianism”. There Farrell proposes two alternatives to justify democracy: The first one holds that all adults, free of physical or mental impairments, are the best judges of their interests and, in its turn, the second one points out that the same adults would be the best judges of their own preferences.

Farrell argues that the former is indefensible by the number of counterexamples we can find in which an adult seems not to know his best objective interest (perhaps knowable by an expert without his intervention) and, at the same time, other examples that show adults opting freely against their own interest. Instead, he openly defends the second argument: adults are the best experts and judges of their own (subjective) preferences. Although we will discuss in the next few paragraphs the assertion about the possibility that expert may have the objective knowledge of another person´s best interest, we will concede the point for now and agree with Farrell that each adult is the best judge of their own preferences.

This is how we could now answer the questions we posed before. I think that most of us would intuitively reject the proposal of experts/officials telling us what food to eat, what sports to practice, what form of social relationships to prefer and so. Of course, with the exceptions of exceptional situations of crisis in which we consciously seek help from experts in each subject, so that they can provide us with, in this case, personalized advice, considering our specific circumstances, beliefs and wishes. On the other hand, the pandemic has left us a clear image of the fallible, provisional, and changing nature of scientific knowledge.

I believe that the perfectionist and scientistic vision of individual life is based on a conception that responds and falls into the following errors:

a) Confusing correlation with causality: Studies on the influence of certain habit or the consumption of certain food or drink on individuals´ health show correlations and no causal links. That is, it cannot be reliably proven that this or that habit produces such a consequence but only that, given two variables, the values of one vary systematically with the homonymous values of the other. This coincidence may respond to an external cause to both (which produces or “causes ” both variables) or by multiple causes that are difficult to unravel at this level. This is obvious to any scientist or expert in each area, but it is forgotten when it is discussed in the public sphere, where not practicing sports “causes” obesity, salt “causes” high pressure and not wearing a face mask seems to “causes” the contagion of the coronavirus.

b) Studies always work with populations, that is, with a sample or group of individuals of a certain sex, age, physical characteristics, etc. that could have a probability of, for example, suffering certain disease. Let´s say- for the purpose of illustration- that certain group of individuals -men over 65 years have a 60% chance of having a heart attack. But this “class” or group probability does not tell us anything about each particular individual being part or not of that 60%. What if a public policy of restricting salt is being imposed on a man with low blood pressure and a very low probability of having a heart attack? Can’t this individual make the decision to consume more salt than recommended by public bodies or professional chambers at his own risk? Let´s remember all the atrocious examples that were experienced during the pandemic about relatives who have not been able to accompany terminally ill patients, penalties even of jail for people who circulated at prohibited hours and contradictory recommendations that prevented individuals from being able, with the public information available, to decide about their possibilities to work, circulate, see their relatives, etc. under threat of sanction.

c) Scientific studies and their practical conclusions are constantly changing. We have lived through this intensely in the last 20months or more of the pandemic, where what at first seemed irrefutable, months later seems shocking. Just as an example, the practically absolute prohibition -in countries as Argentina- for children to walk in the streets the first three months of quarantine. These major shifts in scientific criteria in one area can be observed (perhaps without the speed we see during the pandemic) in many other realms. Continuing with the nutritional example, we can say that the paradigms in this area seem to change drastically and quickly. Only in the last 20 or 30 years has it gone from suggesting that alcohol was bad to recommending a glass of wine a day to prevent heart disease; to try to eliminate meat in all its forms to currently attempt to eliminate all carbohydrates and sugars and to consume only proteins and fats and many more.

But, beyond all these characteristics of scientific knowledge that inform “perfectionist” public policies, we can also raise an even more fundamental point: Even if we could know, reliably and with certainty, -what science would never guarantee- how a certain habit can affect our health or what would happen if we do not met with the ideal, don´t we have any right to choose how to live our lives? When did we renounce to that right in favor of the experts of a group of professional councils or of the civil servants of a Ministry of Health? Should we forbid the individual who wants to dedicate his life to climbing the Himalayas to carry out such an endeavor because of the high risks of his life plan? And the one who practices hang gliding? Don’t these individuals know their own preferences better than anyone else?

And here are some more points added from a higher level of observation:

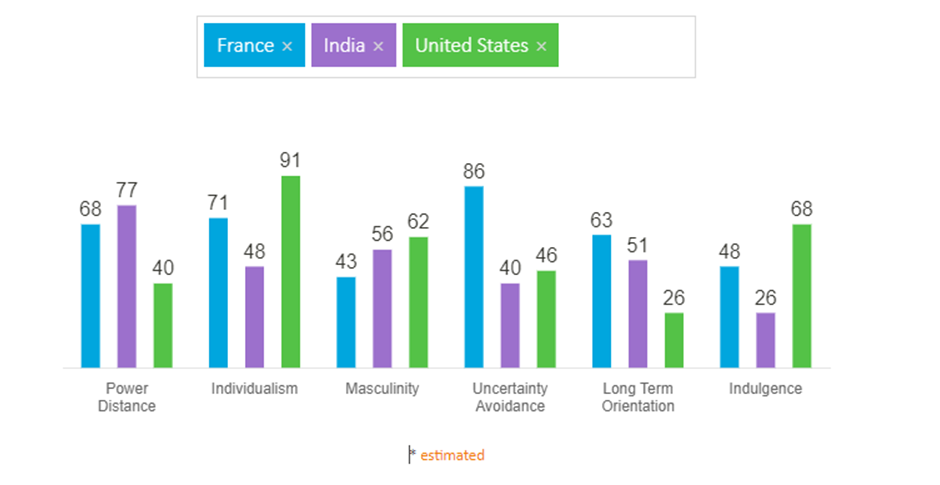

a) Levels of Abstraction: Why might we think that individuals choosing between options are “biased” and when individuals working as government agents in offices creating “nudges” are not biased as other individuals in their daily life? Individuals who work in the civil service or have some degree of professional or scientific specialty, don´t they suffer from the same biases and limitations described in the studies above mentioned, typical of every human being? For example, don´t they choose between theoretical or experimental options for those results presented in a more pleasant way (problem of the architecture of the election) or that confirmed more strongly their hypotheses (confirmation fallacy)?

b) Scientific theories are fallible. Also, some of the results of these experiments may turn out to be incorrect or incomplete in the future. Do we have the right to influence individual decisions based on studies that are, like any scientific theory or experiment, fallible and provisional? After all, isn’t it more worthy for the individual to pay the costs of his bad decision rather than paying the costs of a government agent’s bad decision?

c) Finally, a more philosophical point: How does chance or destiny influence on our daily decisions? Is there a case where the options are presented in a “neutral distribution” way? Let us suppose the case of an individual’s decision regarding the acquisition of medical or retirement insurances (issues that have also been very relevant during the pandemic). The individual must choose between “default options”. The options could be presented to consumers randomly or in a way decided by offerors – but without any central agent deciding-. In the latter case, the options are established by the offerors because they are trying to influence commercially on consumers´ choice and, therefore, it could be said that there is no neutral distribution even though it is not a “nudge” of the public sphere. But, on the other hand, there is a suggestion made by government agents, then the ” nudge ” is intervening in the market, albeit subtly. That is to say that private influence is being replaced by governmental influence, bringing an artificial “architecture” of the choice that did not exist before and, therefore, eliminating randomness. Here we are again facing “levels of abstraction” problem: Don´t “experts” -who propose the ” nudge”- have the same limitations as individuals that interact?

Recapitulating, during this long process we lived the last year and a half since pandemic, quarantine and all the -health, economic, political -measures taken by governments, the question about the scope of our autonomy reemerged. Standing on a platform where philosophical perfectionism and a misunderstood scientism are combined, it has gone from trying to discover patterns of behavior to prescribing ideal results and to opening the door to all kinds of measures, which establish from our right to move freely, if we can work, if we can trade, etc. And what has been more unusual, without explicit limits on the duration of such measures. I think this responds to a trend of thought that had started much earlier. But shouldn’t we take back the reins of our lives as adults? Don’t we know our interests better -or, at least, our preferences- by ourselves? If others believe they know our interests better than us, shouldn´t each of us, considering our preferences, be the best judges of how much risk we want to take? We could think that governments and expert organizations can, in good faith, publish all the information and studies produced and, likewise, could suggest, recommend, and even collaborate to follow the suggestions; but not to compel, prohibit and sanction those who are “wrong” at their own risk.

Of course, this implies taking responsibility for our actions and not demanding or claiming the governments to decide for us or to be accountable for our mistakes. If we decide to climb the Himalayas, we will have to train for many years, buy the appropriate equipment, take out the appropriate insurance, face possible injuries and if something goes wrong, even face death. Ultimately, in each election our desires, our beliefs, our projects, and our philosophical perspectives – that provides- meaning to our lives- come into play. So, we cannot ask the government or the experts to prohibit something from us (because it is risky) or, what is worse, to prohibit it from all citizens, so as not to face the dangers or costs of our eventual mistakes.

We find ourselves – by our decision – facing the paradox that we, given our limitations, cannot make personal and everyday decisions about our work, food or habits, but we can choose legitimately officials, experts or governmental agents that are going to lead us on such tasks. I propose, instead, to reassume our adulthood and start exercising our right to bring the life plan whose consequences we can assume. This, instead of taking it as natural that others decide for us in exchange of unloading on them the responsibility of our own life. Only then we will be able to claim, legitimately, the right to take our own decisions at the risk of being wrong.