2020 is turning into quite the publishing year.

Perhaps every year is like this and I just haven’t been paying attention before. Now, as I actively scan publisher sites and newsletters for upcoming books, there seems to be an abundance of super-interesting new stuff: how is anybody – even someone like me who does this for a living – supposed to keep up?

#1: The year began at full (or stagnating…?) speed with University of Houston professor Dietrich Vollrath‘s Fully Grown: Why a Stagnant Economy is a Sign of Success, With praise by Tyler Cowen and reviews in The Economist and the Wall Street Journal – and actually a lot of good discussions on Twitter – I’m sad that I haven’t taken time to read it. Later, perhaps, on the off-chance that nothing else on this incredible lists comes in the way.

#2: Next up was Diane Coyle‘s Markets, State, and People. Coyle, the endlessly interesting public intellectual/economist and newly(-ish) appointed Professor of Public Policy at Cambridge, is someone we all should read: she manages to be controversial and still balanced, provocative but still interesting. This book, however, seems to be in line with all the other “Third Way” books of last year: Acemoglu and Robinson’s The Narrow Corridor; Raghuram Rajan’s The Third Pillar; Branko Milanovic’s Capitalism, Alone. Crowded field. As I haven’t even gotten around to her previous book on GDP yet, I imagine I’ll read that one first whenever I carve out some time for Coyle.

The curse of modernity is quickly adding up.

#3: Changing gears somewhat – at least in terms of topics – I have started reading Charles Murray‘s Human Diversity: The Biology of Gender, Race, and Class and it’s exactly as provocative as you might think. Delivered, however, with the seriousness of scientific investigation and a massive chip on his shoulder. Still, exactly the kind of antidote to madness that fuels a lot of my priors. I’ll write up a comment or two whenever I finish this 528-page tome.

#4: In a similar vein is the Dutch writer and historian Rutger Bregman‘s Humankind: a Hopeful History, scheduled to be released in June. As Bregman isn’t somebody that I usually agree with, I’m very excited to read this take of his, which is hopefully a mix of Paul Bloom’s End of Empathy, Ruth DeFries’ The Big Ratchet and Paul Seabright’s The Company of Strangers. Sort of like Yuval Harari’s Sapiens but better (and no, I’m not on Team Harari – despite this excellent long-read in The New Yorker).

#5: Going back a little bit to what I think is chronologically the next book to be released (on Tuesday March 10 in the U.S., but not until April in the U.K.) is Robert Bryce’s A Question of Power: Electricity and the Wealth of Nations. Having recently written a piece on electricity generation and being into the weeds about climate change and emissions, I’m very curious about this take on electricity as a critical source for our prosperity. I hope it reads a little like an improved version of Zubrin’s best chapters in Merchants of Despair.

#6: March is also the month for Angus Deaton and Anne Case‘s Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Amazon says it’s already out in the U.K.) Their hugely successful and highly relevant pet project for the last few years, Deaton and Case’s case(!) for how rising morbidity rates indicate a collapse of the fabric of society is a pretty standard one by now: globalization, economic inequality, the hollowing-out of tight-knit communities and the various forces that may have fueled this.

The reviews are already popping up left and right (WSJ, Financial Times) and their session was the most exciting and most talked-about at the ASSA meeting in San Diego. As I understand it, the latest findings is that American life expectancy – that pesky ever-increasing number that fell in recent years, in no small part due to overdoses and opioids – has recovered and is now again on the up-tick. Maybe Deaton and Case’s book will be one for an odd historic event rather than foreshadowing “The Future of Capitalism” (also, what’s up with shoving ‘Future of Capitalism’ into your titles?!).

#7: In a similar topic, Robert Putnam – yes, the Harvard professor famous for Bowling Alone and the idea of social capital – is back with another sweeping analysis of what’s gone wrong with American society. The Upswing: How America Came Together a Century Ago and How We Can Do It Again, coming out in June, is bound to make a lot of waves and receive a lot of attention by social commentators.

#8: Officially published just yesterday is John Kay and former Bank of England Governor Mervyn King‘s Radical Uncertainty: Decision-Making for an Unknowable Future. Admittedly, this is the book I’m least excited about on this list. Reviewing King’s 2016 End of Alchemy – where King discussed his experiences of the financial crisis and the global banking system – for the Financial Times, John Kay discussed exactly that: the title? “The Enduring Certainty of Radical Uncertainty.” Somebody please press the snooze button. Paul Krugman’s 4000 word review of End of Alchemy ought to be enough; I’d be surprised if Kay and King brings something new to the table in thus poorly-titled release (though, of course the fringe already loves it).

The Really Good Stuff

While the above eight titles are surely worth at least some of your time, the next five are worth all of it.

#9: I’ll begin with my two biggest hypes: Matt Ridley‘s How Innovation Works: And Why It Flourishes in Freedom, coming out May 14th in the U.K. and May 19th in the U.S. The author of The Rational Optimist and The Evolution of Everything is back with another 400-page rundown of a deep-seated and hyper-relevant topic: how do societies innovate and progress? What conditions assist it, and which obstacles prevent it?

I expect a lot of spontaneous order-type arguments, debunked Great Man fallacies, and some Mariana Mazzucato take-downs.

#10: The second hype, William Quinn and John Turner‘s Book and Bust: A Global History of Financial Bubbles. Since John first told me about this book over a year-and-a-half ago, I’ve been super excited – I’m a big fan of his work – and I’m looking forward to receiving my review copy in the next couple of weeks. Publication date: August.

#11: For somebody who writes about bubbles and financial markets more than most people think healthy, I’m gonna get a warm-up in MIT professor Thomas Levenson‘s Money for Nothing: The South Sea Bubble & The Invention of Modern Capitalism. What’s with all these books on historical financial bubbles? Yes, you’re right: 2020 marks the three-hundred year anniversary of the South Sea Bubble, that iconic period of John Law in France and the similar government funding scheme in England will surely receive a lot of attention this year.

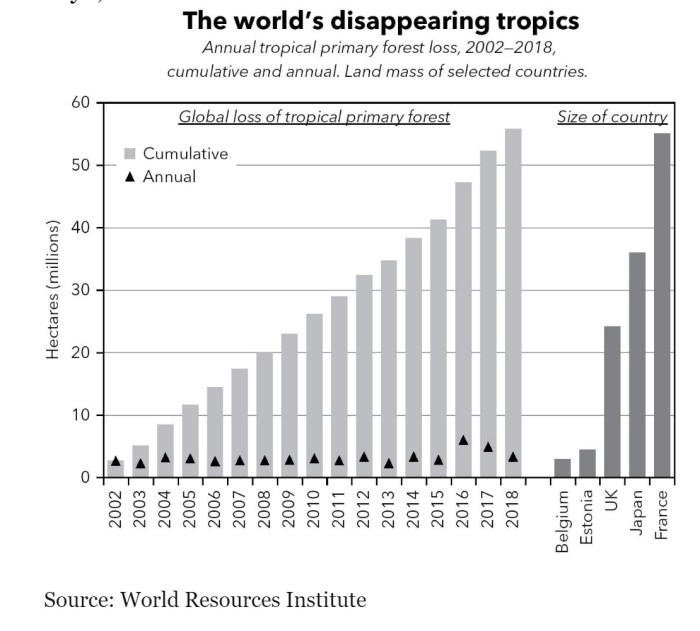

#12: Some environmental stuff at last: Bjørn Lomborg, the outspoken author and voice of reason in the climate change space announced that his False Alarm: How Climate CHange Panic Costs Us Trillions, Hurts The Poor, and Fails To Fix the Planet will be published in June this year! While possibly the least boring book on this list, the title receives lowest possible marks. What overworked publisher decided that this page-long subtitle was a good idea?!

#13: Also, Alex Epstein of the Centre for Industrial Progress and host of Power Hour (one of my all-time favorite podcasts) has been working on an update to his hugely popular The Moral Case for Fossil Fuels. As far as I understand, we’re to receive an updated and revised version in August – the Moral Case for Fossil Fuels 2.0!

So. The next six months have at least thirteen pretty interesting books coming up. I imagine there are a bunch more for the rest of the year – and a few I have completely overlooked.

Also, after this burst of links, Amazon should probably offer Notes On Liberty an affiliate program.

In sum: you can see my fields of interests overlapping here: (1) financial history and financial markets; (2) environment, climate change, and its solutions; (3) Big Picture society stories, preferably by interesting or quantitatively savvy authors. Not enough on the fourth big interest of mine: (4) money and monetary economics – particularly in historical contexts. Perhaps not, as David Birch’s Before Babylon, Beyond Bitcoin is on my desk, and I’m currently re-reading William Goetzmann’s Money Changes Everything – both first released in 2017.

Also: the absence or underrepresentation of women (or ethnic minorities or any other trait you care a lot about) might disturb you: 2 out of 17 authors women (4 out of 27 authors mentioned) – Needless to say, it must be because I’m sexist.

Post-script: Ha! As I just heard about Stephanie Kelton‘s upcoming book The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy, I’m gonna quickly add it to the list and satisfy both of my qualms above: not enough women (now: 3/18 authors!), and not enough monetary economics. Splendid!

Happy reading, everyone!