The notion of the person is constantly renegotiated and is at stake between groups situated within the same political entity as well as between neighboring political entities. With advent of [France’s colonial] district register and the resulting written registration of identity, the notion of a person acquired a greater fixity. It became much more difficult to change identity or even to modify the spelling of one’s first or last name. Since it could no longer affect the components of the person, the negotiation of identity shifted, as in the case of the West, onto other sectors of social and individual life. (135)

This is from the French anthropologist (and high school friend of our own Jacques Delacroix) Jean-Loup Amselle, in his book Mestizo Logics: Anthropology of Identity in Africa and Elsewhere. The book is hard to read. The English translation (the one I’m reading) was published by Stanford University Press in 1998, but the original French language version came out in 1990. Between the translation and the fact that the book was written for specialists in the field of political anthropology and the region of French Sudan, strenuous effort was required on my part to stay focused and motivated to finish the book. The preface alone is worth the price of admission, though, especially if you’ve been following my blogging with any great interest over the years.

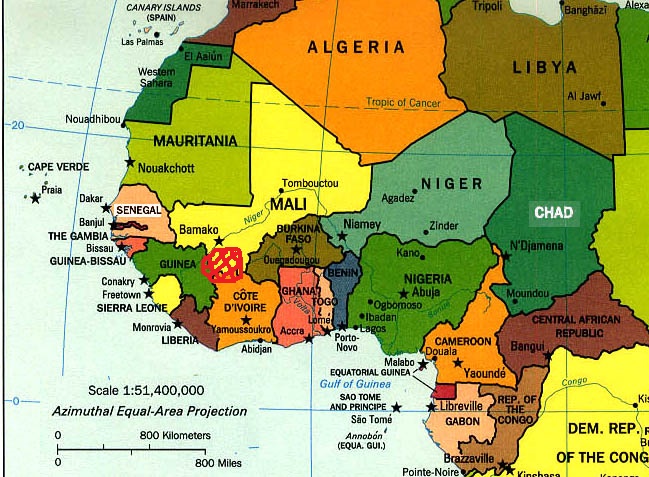

My intent is not to write a review, but rather to build off Amselle’s work and present some of my efforts in blog form here at NOL. But first, a map of the region, Wasolon, that Amselle specializes in:

Wasolon is that big red marking that I’ve drawn on the map. You can see that it’s about as big as Sierra Leone. Just for clarity’s sake, here is a second map with a closer view of Wasolon:

Amselle’s argument for why his approach to identity is superior to others’ is convincing. He performed all of his fieldwork (15 years’ worth as of 1990) in Wasolon, or briefly in neighboring areas, reasoning that “research within numerous regions of a well-circumscribed area […] has allowed me to observe systems of transformation [in] societies that have been in contact for centuries. This has protected me from being forced into large analytical leaps and from engaging in [the current anthropological trends of] abstract comparativism and the identification of structures (xii-xiii).” This defense of his methodology, coupled with his insights on French colonial administration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, gives me reason to believe that Amselle’s work is an excellent blueprint for better understanding the complete and utter failure of post-colonial states and the violence these collective failures have produced.

I want to take a specific route using the introductory quote, even though I could take a number of different routes using that passage. I could, for example, focus on the invention of the individual and muse about its consequences in regards to the rise of the West. I could go on and on about how other societies had writing – but not the individual- and therefore did not have the institutions necessary for “capitalism” that the West did around the 16th century. Et cetera, et cetera. Instead, I’m going to take a geopolitical route (the West is still practicing colonialism) that has a decidedly philosophical direction to it (nationalism and ethno-nationalism are both bullhooey).

First, the geopolitical context. Wasolon was basically a war zone in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was an important producer of cotton, a minor producer of rubber and ivory, and a net exporter of slaves. Wasolon was unfortunate enough to be caught between Saharan empires backed by Arabic culture, money, and technology, and coastal empires recently enriched through cultural, economic, and technological exchange with rapidly-expanding European populations. Caught between these two geographic poles, polities in Wasolon oscillated between being decentralized chiefdoms, small independent states, empire builders themselves, and vassals of empires. In such an uncertain setting, the identity of people themselves necessarily oscillated as often as their political systems did.

When the French arrived militarily on the scene (there was already a long history of economic, political, and cultural exchange between the “French” and Wasolonians; I put French in quotation marks because, of course, many Europeans found it to be much easier to use “French” as an identity in French Sudan rather than their own), Wasolon was home to many decentralized chiefdoms, and they were all in the midst of a protracted and brutal war with the Samori Empire, a Saharan polity that rose quickly and ruthlessly to prominence in the late 19th century.

The Samori Empire – which the French military was in contact with due to its centralized political structure (it had a bureaucracy and an organized military, for example) – claimed Wasolon as a vassal state and the French, out of ignorance or expediency (to attribute it to malice gives French central planners too much credit), simply took Samori at its word (a policy that continues to play out to this day in international affairs, but more on this below).

The French military commanders and, later, colonial administrators eventually figured out that Wasolon was not a loyal vassal. From the French perspective, the resisting chiefdoms in Wasolon had formed an alliance against the Samori Empire, and this alliance was based on an ethnic solidarity shared by all Fulani. Amselle labors to make the point that this alliance was based on a “mythical charter” long prominent in Fula oral traditions (and has some basis in the historical accounts of Arab and European travelers). This “mythical charter” served as the basis for the French colonial understanding of the Fula and eventually for the notion of a Fulani ethnic identity. The problem here is that the “mythical charter” was just that: a myth.

I’ll start by extracting an insight from the footnotes:

As we saw in Chap. 5, colonial ethnology merely reproduces this local political theory by taking it literally, thereby assimilating these “mythical charters” to a real historical process. Such a reproduction is what makes this ethnology truly colonial. (179)

In the Chapter 5 that Amselle alludes to in his footnotes, Mestizo Logics explains how the Fula people of Wasolon adopted fluid political identities over the centuries, depending on who was in power and who was about to be in power. This fluidity played, and continues to play, a much more important role in how people identified themselves politically (“local political theory”) than either culture or language.

Amselle illustrates this point best by pointing out that a number of chiefdoms in Wasolon claimed to be Fula at the time of the French conquests in the late 19th century, but that the populations spoke a different language than the Fula and were culturally distinct from the Fula (these Wasolon chiefdoms claiming Fulaniship were Banmana and Maninka in language and culture rather than Fula). Amselle then points out that Fula chiefdoms existed outside of Wasolon that don’t claim to be Fula – even though they are culturally and linguistically Fula – and instead identified as something more politically expedient (he doesn’t elaborate on what those non-Fula Fulani identify as, only that they did, and still do).

The French state’s act of writing down and categorizing this “mythical charter” as a distinct feature of Wasolon’s Fulani thus created the Fula ethnic group and, through imperial governance, ensconced this new group into its empire’s hierarchy based on traits that ethnographers, colonial administrators, historians, and managers of state-run corporations had recorded (accounts written by merchants not connected to the state in some way could not be trusted, of course).

Basically, when the French showed up to build their empire in west Africa they bought the narrative espoused by a couple of the factions in the region and based their empire (which was only feasible with the advent of peace in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars) on that narrative. The results of this policy are eye-opening. Aside from the fact that the present-day states of Mali, Cote d’Ivoire, and Guinea are failures, the old rules of fluid identity used by Wasolonians for political and economic reasons were erased and new rules, based on bureaucratic logic (“ethnicity”), were wrested into place by the French imperial apparatus. These new ethnic identities soon took on characteristics, ascribed to them by others, that quickly became stereotypes. The ethnic groups with good stereotypes (like being hard-working) ended up – you guessed it – in positions of power, first in France’s imperial apparatus and then for a short time after independence.

Sound familiar?

If it doesn’t, think about international governing institutions (IGOs) like the United Nations or the World Bank for a moment. Why don’t these institutions recognize the likes of Kurdistan, Baluchistan, or South Ossetia? Is it because these IGOs are evil and oppressive, or simply because these bureaucracies cannot adapt quickly enough to a world where identity and the necessities of political economies are always in flux?

This phenomenon is not limited to post-colonial Africa, either. Think about African-Americans here in the United States and the stereotypes attributed to them. Those stereotypes – good and bad – are a direct result of bureaucracy.

Individualism, to me, is the best way to tackle the long-standing problem created by colonial logic abroad, and racism at home. Government programs that seek to help groups by taking from one and giving to another are just an extension of the bureaucratic logic revealed by Amselle’s work in French West Africa. But what is a good way to go about implementing a more individualized world? Open borders? Federation?