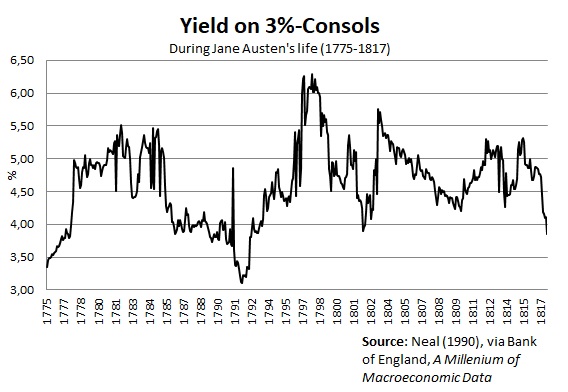

Following my Mr. Darcy piece that outlined the use and convenience of British government debt instruments in the eighteenth (and predominantly the nineteenth) century, I thought to extend the discussion to two particular financial instruments. In addition to the Consols (homogenous, tradeable perpetual government debt) that formed the center of public finance – and whose active secondary market that made them so popular as savings devices – the Bill of Exchange was the prime instrument used by merchants for financing trade and settling debts.

The complementarity of the Consol and the Bill in international finance, roughly from the South Sea Bubble (1720) to the end of Napoleon (1815), was the “secret of success for international finance” (Neal 2015: 101) and arose without an overarching plan, i.e. rather spontaneously. As the Consol is more easily understood for a modern reader, and the Bill is both more ancient and less well understood, I’ll focus the bulk of my attention on the latter.

According to Anderson (1970: 90), the Bill constituted “a decisive turning-point in the development of the English credit system,” but is much older than that. In practice, it was a paper indicating debt and a time for repayment, allowing financing of current trade. Cameron (1967:19) writes that the Bill

was far more ancient than either the banknote or the demand deposit; it had been developed in the Middle Ages. At first the bill was used as a device for avoiding the cost and risks of shipping coin or bullion over great distances, then as a credit instrument which circumvented the Church’s prohibition of usury. When it first came to be used as a means of current payment is a moot question that may never be answered, but that it was so used in eighteenth-century England is beyond doubt.

The Bill was predominantly used in coastal cities in the Mediterranean and around the North-Sea, becoming frequent perhaps in the 1700s. One observer even dates an early instance of its use to 1161, and it was of standard use among traveling traders, merchants and brokers throughout the Middle Ages (Cassis & Cottrell 2015: 12). Occasionally – warranting a discussion of its own – Bills in England became “so widespread that they drove out even banknotes” (Cameron 1967: 19).

There is an unfitting competition among financial historians as to who can produce the most persuasive, informative or complicated schedule for how Bills worked (I know of at least four similar, yet uncredited, renditions). Here’s Anthony Hotson’s (2017: 92) attempt from last year:

- We start, counter-intuitively, in the top-right corner. Andrew, an English exporter of Apples, draws up a Bill on Bas, a Amsterdam maker of Bankets – a Dutch pastry. Bas, having no coin/gold available to pay Andrew – either because he won’t have the funds until after he has sold his apple-flavored(!) Bankets, or because the risk of loss or cost of transportation is too great – accepts the Bill and returns it to Andrew.

- Having returned it to Andrew, we now have a debt and a financial instrument; Bas has promised to pay Andrew £x for the apples in 90 days, a common duration for a Bill of exchange.

- But like most merchants, Andrew cannot wait 90 days for payment; he has sold and shipped his Apples, but needs funds for himself (feeding his family, or investing in new Apple-harvesting equipment etc). In the heyday of British financial markets, Andrew could simply visit a bank, Bill-broker or the London financial markets himself, and offer to sell the Bill there. Of course, Andrew won’t be able to sell the Bill for £x, since his buyer is effectively providing him with a loan for 90 days. The bank, bill-broker or financial market trader will discount the Bill with the going interest rate (say 6%, for one-quarter of a year, so ~1.5%), paying at most £0.985x for the Bill. Besides, there is a risk-of-default element involved, so the buyer applies a risk premium as well, perhaps buying the Bill at £0.95x.

- In the schedule above Hotson uses the Bill trade to show how merchants trading Bills could net out their respective debts and minimize the need to send payment across the British channel. For (3) and (4), then, we replace the banker with an English importer – Dave – of Dutch goods (perhaps tin-glazed pottery) looking for a way to pay his Amsterdam pottery supplier, Cremer. Instead of shipping gold to Amsterdam, Dave may purchase Andrew’s Bill, and settle his account with Cremer by sending along the Bill drawn on Bas. Once the 90 days are up, Cremer can simply wander over to Bas’ pastry shop and present him with the Bill to receive payment for the goods Cremer already shipped to England.

This venture can – and usually was – made infinitely more complicated; we can add brokers and discounting banks in every transaction between Andrew, Bas, Dave and Cremer, as well as a number of endorsers and re-discounters. In his popular book Exorbitant Privilege, Barry Eichengreen recounts a 12-step, several-pages long account for how a U.S. importer of coffee and his Brazilian supplier both get credit and signed papers from their local (New York + Brazil) banks, how both banks send their endorsed bills to their London correspondent banks, and some investor in the London money markets purchase (and perhaps re-sell) the Bill that eventually settles the transaction between the American coffee importer and the Brazilian farmer.

Although it might sound excessive, complicated and impossible to overlook, the entire process simplified business for everyone involved – and allowed business that otherwise couldn’t have been done. In econo-speak, the Bill of Exchange set within a globalizing financial system, extended the market for merchants and farmers and customers alike, lowered transaction costs and solved information asymmetries so that trade could take place.

Turning to the opposite end of the maturity spectrum, the Consol as a perpetual debt by the government was never intended to be repaid. Having a large secondary market of identical instruments, allowed investors or financial traders everywhere to pass Gorton’s No-Questions-Asked criteria for trade. A larger market for government debt, such as after Britain’s wars in the late-1700s and early 1800s, allowed dealers in financial markets to a) be reasonably certain that they could instantly re-sell the instrument when in need of cash, and b) quickly and effortlessly identify it. These aspects contributed to traders applying a smaller risk premium to the instrument and to be much more willing to hold it.

While the Bills were the opposite of Consols in terms of homogeniety (they all consisted of different originators, traders, and commodities), there developed specialized dealers known as Discount Houses whose task it was to assess, buy, and sell Bills available (Battilosso 2016: 223). Essentially, they became the credit rating institutions of the early modern age.

Together these two instruments, the Bills of Exchange and the Consols, laid the foundations for the modern financial capitalism that develops out of the Amsterdam-London nexus of international finance.

Source:

Source:

Source:

Source:  So

So