democratic socialism

Nightcap

- It’s time for socialists to re-embrace freedom Jodi Dean, Los Angeles Review of Books

- Hagia Sophia and the politics of heritage Elif Kalaycioglu, Duck of Minerva

- The nation-state versus the civilization-state Bruno Maçães, Noema

- Yo-Yo Ma and the acid-free box Shepard Barbash, City Journal

Nightcap

- Normal Joe (Biden) and the 2020 election Jacques Delacroix, NOL

- More campaign finance fiction Ethan Blevins, NOL

- The Good Life vs reality Mary Lucia Darst, NOL

- Prediction: Trump-Sanders 2016 Rick Weber, NOL

- “Medicare For All” will never work: a Brazilian view Bruno Gonçalves Rosi, NOL

- Bernie fans should want Bernie to lose the primary Bill Rein, NOL

Nightcap

- Singapore’s quarrel over colonialism Stephen Dziedzic, Interpreter

- Extreme economies: failure Joakim Book, NOL

- A victory over Sweden’s colonialism? Carl & Laiti, Al Jazeera

- The wrong models of democratic socialism Jacques Delacroix, NOL

Sunday Poetry: Gender Equality where it matters? The Scandinavian Unexceptionalism

Deja-Vu! Social Democrats once again bring up the topic of “Democratic Socialism” to cure all of the evils of the world. Once again, the Scandinavian countries (Sweden, Finnland, Denmark and Norway) are used as an example of how “a third way Socialism” can work. Although I still would consider myself young, I have already lost all of my stamina to engage in the same debates all over again until they pop up again a few months after.

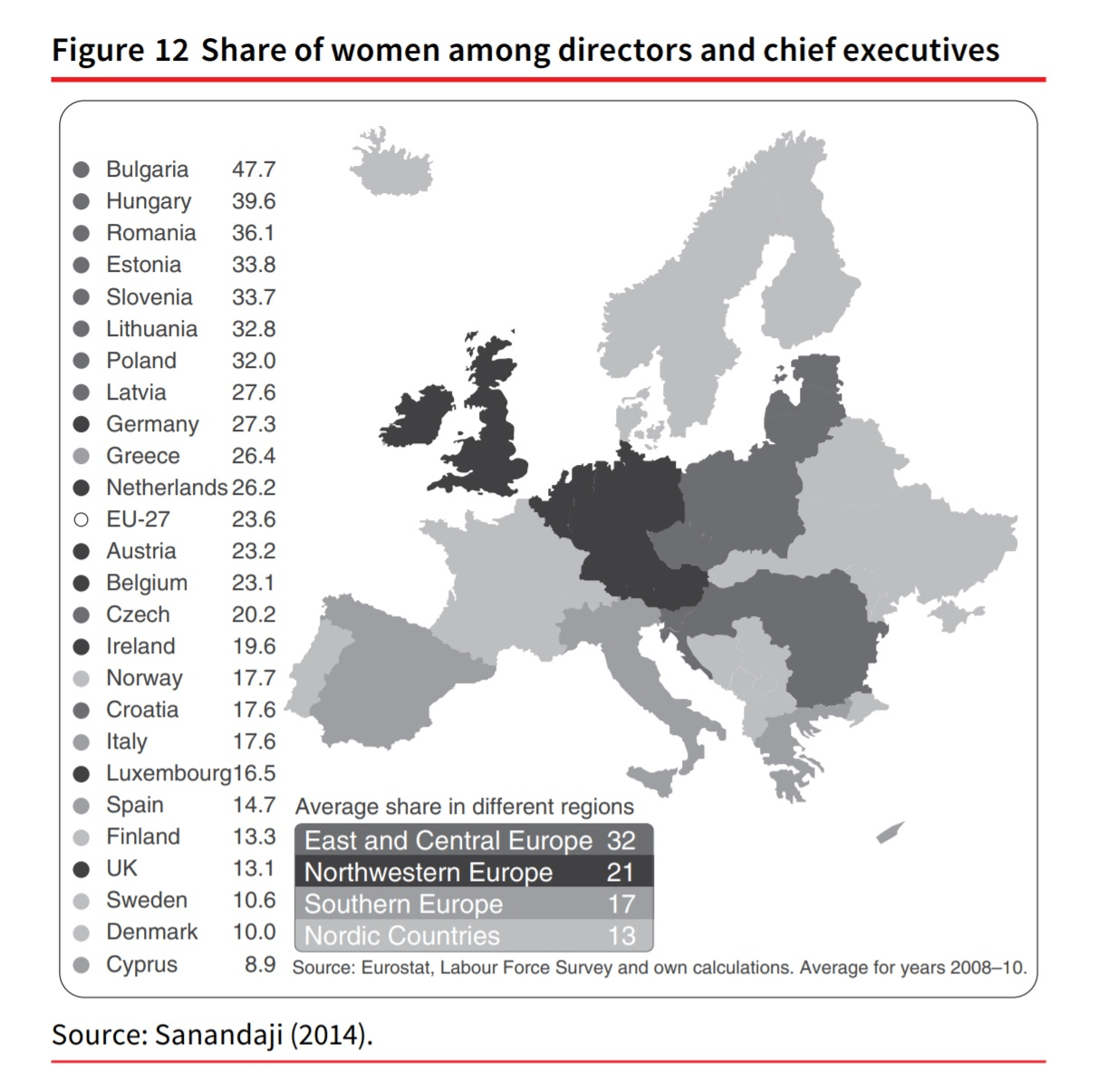

So, instead of pointing out the fallacy in labelling the Scandinavian countries moderately socialist (Nima Sanandaji, for example, does an excellent job in doing so), I want to look at one aspect in particular: The myth of peak emancipation of woman in the labour market in these countries. So apologies for neglecting Poetry once again for the sake of interesting information. Have a look at the following graphic and the remarks by Sanandaji:

“Some boards in Nordic nations are actively engaged in how the companies they represent are run. Others have a more supervisory nature, meeting a few times a year to oversee the work of the management. The select few individuals who occupy board positions – many of whom reach this position after careers in politics, academia and other non-business sectors – have prestigious jobs. They are, however, not representative of those taking the main decisions in the business sector. The important decisions are instead taken by executives and directors. Typically individuals only reach a high managerial position in the private sector after having worked for a long time in that sector or successfully started or expanded a firm as an entrepreneur. The share of women to reach executive and director positions is the best proxy for women’s success in the business world. Eurostat has gathered data for the share of women among ‘directors and chief executives’ in various European countries between 2008 and 2010. The data show that Nordic nations all have low levels of women at the top of businesses. In Denmark and Sweden, only one out of ten directors and chief executives in the business world are women. Finland and the UK fare slightly better. Those Central and Eastern European countries for which data exist have much higher representation.

[…]

A key explanation lies in the nature of the welfare state. In Scandinavia, female-dominated sectors such as health care and education are mainly run by the public sector.

A study from the Nordic Innovation Centre (2007: 12–13) concludes: Nearly 50 per cent of all women employees in Denmark are employed in the public sector. Compared to the male counterpart where just above 15 per cent are employed in the public sector. This difference alone can explain some of the gender gap with respect to entrepreneurship. The same story is prevalent in Sweden. The lack of competition reduces long-term productivity growth and overall levels of pay in the female-dominated public sector. It also combines with union wage-setting to create a situation where individual hard work is not rewarded significantly: wages are flat and wage rises follow seniority, according to labour union contracts, rather than individual achievement. Women in Scandinavia can, of course, become managers within the public sector, but the opportunities for individual career paths, and certainly for entrepreneurship, are typically more limited compared within the private sector.

If you are interested in the whole book, it is completely available online for free.

I wish you all a pleasant Sunday.

2019: Year in Review

It’s been a heck of a year. Thanks for plugging along with Notes On Liberty. Like the world around me, NOL keeps getting better and better. Traffic in 2019 came from all over the place, but the usual suspects didn’t disappoint: the United States, United Kingdom, Canada, India, and Australia (in that order) supplied the most readers, again.

As far as most popular posts, I’ll list the top 10 below, but such a list doesn’t do justice to NOL and the Notewriters’ contribution to the Great Conversation, nor will the list reflect the fact that some of NOL‘s classic pieces from years ago were also popular again.

Nick’s “One weird old tax could slash wealth inequality (NIMBYs, don’t click!)” was in the top ten for most of this year, and his posts on John Rawls, The Joker film, Dominic Cummings, and the UK’s pornographer & puritan coalition are all worth reading again (and again). The Financial Times, RealClearPolicy, 3 Quarks Daily, and RealClearWorld all featured Nick’s stuff throughout 2019.

Joakim had a banner year at NOL, and four of his posts made the top 10. He got love from the left, right, and everything in between this year. “Elite Anxiety: Paul Collier’s ‘Future of Capitalism’” (#9), “In Defense of Not Having a Clue” (#8), and “You’re Not Worth My Time” (#7) all caused havoc on the internet and in coffee shops around the world. Joakim’s piece on Mr Darcy from Pride and Prejudice (#2) broke – no shattered – NOL‘s records. Aside from shattering NOL‘s records, Joakim also had excellent stuff on financial history, Richard Davies, and Nassim Taleb. He is also beginning to bud as a cultural commentator, too, as you can probably tell from his sporadic notes on opinions. Joakim wants a more rational, more internationalist, and more skeptical world to live in. He’s doing everything he can to make that happen. And don’t forget this one: “Economists, Economic History, and Theory.”

Tridivesh had an excellent third year at NOL. His most popular piece was “Italy and the Belt and Road Initiative,” and most of his other notes have been featured on RealClearWorld‘s front page. Tridivesh has also been working with me behind the scenes to unveil a new feature at NOL in 2020, and I couldn’t be more humbled about working with him.

Bill had a slower year here at NOL, as he’s been working in the real world, but he still managed to put out some bangers. “Epistemological anarchism to anarchism” kicked off a Feyerabendian buzz at NOL, and he put together well-argued pieces on psychedelics, abortion, and the alt-right. His short 2017 note on left-libertarianism has quietly become a NOL classic.

Mary had a phenomenal year at NOL, which was capped off with some love from RealClearPolicy for her “Contempt for Capitalism” piece. She kicked off the year with a sharp piece on semiotics in national dialogue, before then producing a four-part essay on bourgeois culture. Mary also savaged privileged hypocrisy and took a cultural tour through the early 20th century. Oh, and she did all this while doing doctoral work at Oxford. I can’t wait to see what she comes up with in 2020.

Aris’ debut year at NOL was phenomenal. Reread “Rawls, Antigone and the tragic irony of norms” and you’ll know what I’m talking about. I am looking forward to Dr Trantidis’ first full year at NOL in 2020.

Rick continues to be my favorite blogger. His pieces on pollution taxes (here and here) stirred up the libertarian faithful, and he is at his Niskanenian best on bullshit jobs and property rights. His notes on Paul Feyerabend, which I hope he’ll continue throughout 2020, were the centerpiece of NOL‘s spontaneity this year.

Vincent only had two posts at NOL in 2019, but boy were they good: “Interwar US inequality data are deeply flawed” and “Not all GDP measurement errors are greater than zero!” Dr Geloso focused most of his time on publishing academic work.

Alexander instituted the “Sunday Poetry” series at NOL this year and I couldn’t be happier about it. I look forward to reading NOL every day, but especially on Sundays now thanks to his new series. Alex also put out the popular essay “Libertarianism and Neoliberalism – A difference that matters?” (#10), which I suspect will one day grow to be a classic. That wasn’t all. Alex was the author of a number of my personal faves at NOL this year, including pieces about the Austro-Hungarian Empire, constructivism in international relations (part 1 and part 2), and some of the more difficult challenges facing diplomacy today.

Edwin ground out a number of posts in 2019 and, true to character, they challenged orthodoxy and widely-held (by libertarians) opinions. He said “no” to military intervention in Venezuela, though not for the reasons you may think, and that free immigration cannot be classified as a right under classical liberalism. He also poured cold water on Hong Kong’s protests and recommended some good reads on various topics (namely, Robert Nozick and The Troubles). Edwin has several essays on liberalism at NOL that are now bona fide classics.

Federico produced a number of longform essays this year, including “Institutions, Machines, and Complex Orders” and “Three Lessons on Institutions and Incentives” (the latter went on to be featured in the Financial Times and led to at least one formal talk on the subject in Buenos Aires). He also contributed to NOL‘s longstanding position as a bulwark against libertarian dogma with “There is no such thing as a sunk cost fallacy.”

Jacques had a number of hits this year, including “Poverty Under Democratic Socialism” and “Mass shootings in perspective.” His notes on the problems with higher education, aka the university system, also garnered plenty of eyeballs.

Michelangelo, Lode, Zak, and Shree were all working on their PhDs this year, so we didn’t hear from them much, if at all. Hopefully, 2020 will give them a bit more freedom to expand their thoughts. Lucas was not able to contribute anything this year either, but I am confident that 2020 will be the year he reenters the public fray.

Mark spent the year promoting his new book (co-authored by Noel Johnson) Persecution & Toleration. Out of this work arose one of the more popular posts at NOL earlier in the year: “The Institutional Foundations of Antisemitism.” Hopefully Mark will have a little less on his plate in 2020, so he can hang out at NOL more often.

Derrill’s “Romance Econometrics” generated buzz in the left-wing econ blogosphere, and his “Watson my mind today” series began to take flight in 2019. Dr Watson is a true teacher, and I am hoping 2020 is the year he can start dedicating more time to the NOL project, first with his “Watson my mind today” series and second with more insights into thinking like an economist.

Kevin’s “Hyperinflation and trust in ancient Rome” (#6) took the internet by storm, and his 2017 posts on paradoxical geniuses and the deleted slavery clause in the US constitution both received renewed and much deserved interest. But it was his “The Myth of the Nazi War Machine” (#1) that catapulted NOL into its best year yet. I have no idea what Kevin will write about in 2020, but I do know that it’ll be great stuff.

Bruno, one of NOL’s most consistent bloggers and one of its two representatives from Brazil, did not disappoint. His “Liberalism in International Relations” did exceptionally well, as did his post on the differences between conservatives, liberals, and libertarians. Bruno also pitched in on Brazilian politics and Christianity as a global and political phenomenon. His postmodernism posts from years past continue to do well.

Andrei, after several years of gentle prodding, finally got on the board at NOL and his thoughts on Foucault and his libertarian temptation late in life (#5) did much better than predicted. I am hoping to get him more involved in 2020. You can do your part by engaging him in the ‘comments’ threads.

Chhay Lin kept us all abreast of the situation in Hong Kong this year. Ash honed in on housing economics, Barry chimed in on EU elections, and Adrián teased us all in January with his “Selective Moral Argumentation.” Hopefully these four can find a way to fire on all cylinders at NOL in 2020, because they have a lot of cool stuff on their minds (including, but not limited to, bitcoin, language, elections in dictatorships, literature, and YIMBYism).

Ethan crushed it this year, with most of his posts ending up on the front page of RealClearPolicy. More importantly, though, was his commitment to the Tocquevillian idea that lawyers are responsible for education in democratic societies. For that, I am grateful, and I hope he can continue the pace he set during the first half of the year. His most popular piece, by the way, was “Spaghetti Monsters and Free Exercise.” Read it again!

I had a good year here, too. My pieces on federation (#3) and American literature (#4) did waaaaaay better than expected, and my nightcaps continue to pick up readers and push the conversation. I launched the “Be Our Guest” feature here at NOL, too, and it has been a mild success.

Thank you, readers, for a great 2019 and I hope you stick around for what’s in store during 2020. It might be good, it might be bad, and it might be ugly, but isn’t that what spontaneous thoughts on a humble creed are all about? Keep leaving comments, too. The conversation can’t move (forward or backward) without your voice.

The long-run risks of Trump’s racism

This week, the United States and much of the world has been reeling from Trump’s xenophobic statements aimed at four of his Democratic opponents in Congress. But the U.S. economy continues to perform remarkably well for the time being and despite his protectionist spasms, Trump is widely considered a pro-growth, pro-business President.

This has led some classical liberals to consider Trump’s populist rhetoric and flirtations with the far right to be a price worth paying for what they see as the safest path to keeping the administrative state at bay. Many classical liberals believe the greater risk to liberty in the U.S. is inevitably on the left with its commitment to expanding welfare-state entitlements in ways that will shrink the economy and politicize commercial businesses.

In ‘Hayek vs Trump: The Radical Right’s Road to Serfdom’, Aris Trantidis and I dispute this complacency about authoritarianism on the right. In the article, now forthcoming in Polity, we re-interpret Hayek’s famous The Road to Serfdom in light of his later work on coercion in The Constitution of Liberty.

We find that only certain forms of state intervention, those that diminish the rule of law and allow for arbitrary and discriminatory administrative oversight and sanction, pose a credible risk of turning a democratic polity authoritarian. A bigger state, without more discretionary power, does not threaten political liberty. Although leftwing radicals have in the past shown disdain for the rule of law, today in the U.S. and Europe it is the ideology of economic nationalism (not socialism) that presently ignores democratic norms. While growth continues, this ideology may appear to be compatible with support for business. But whenever the music stops, the logic of the rhetoric will lead to a search for scapegoats with individual businesses in the firing line.

Several countries in Europe are much further down the 21st road to serfdom than the U.S., and America still has an expansive civil society and federal structures that we expect to resist the authoritarian trend. Nevertheless, as it stands, the greatest threat to the free society right now does not carry a red flag but wears a red cap.

Here is an extract from the penultimate section:

The economic agenda of the Radical Right is an extension of political nationalism in the sphere of economic policy. While most Radical Right parties rhetorically acknowledge what can be broadly described as a “neoliberal” ethos – supporting fiscal stability, currency stability, and a reduction of government regulation – they put forward a prominent agenda for economic protectionism. This is again justified as a question of serving the “national interest” which takes precedence over any other set of values and considerations that may equally drive economic policy in other political parties, such as individual freedom, social justice, gender equality, class solidarity, or environmental protection. Rather than a principled stance on government intervention along the traditional left-right spectrum, the Radical Right’s economic agenda can be described as mixing nativist, populist and authoritarian features. It seemingly respects property and professes a commitment to economic liberty, but it subordinates economic policy to the ideal of national sovereignty.

In the United States, President Trump has emerged to lead a radical faction from inside the traditional right-wing Republican Party on a strident platform opposing immigration, global institutions, and current international trade arrangements that he portrayed as antagonistic to American economic interests. Is economic nationalism likely to include the type of command-and-control economic policies that we fear as coercive? Economic nationalism can be applied through a series of policies such as tariffs and import quotas, as well as immigration quotas with an appeal to the “national interest.”

This approach to economic management allows authorities to treat property as an object of administration in a way similar to the directions of private activity which Hayek feared can take place in the pursuit of “social justice.” It can take the form of discriminatory decisions and commands with a coercive capacity even though their authorization may come from generally worded rules. Protectionism can be effectuated by expedient decisions and flexible discretion in the selection of beneficiaries and the exclusion of others (and thereby entails strong potential for discrimination). The government will enjoy wide discretion in identifying the sectors of the economy or even particular companies that enjoy such a protection, often national champions that need to be strengthened and weaker industries that need to be protected. The Radical Right can exploit protectionism’s highest capacity for partial discriminatory applications.

The Radical Right has employed tactics of attacking, scapegoating, and ostracizing opponents as unpatriotic. This attitude suggests that its policy preference for economic nationalism and protectionism can have a higher propensity to be arbitrary, ad hoc and applied to manipulate economic and political behavior. This is perhaps most tragically demonstrated in the case of immigration restrictions and deportation practices. These may appear to coerce exclusively foreign residents but ultimately harm citizens who are unable to prove their status, and citizens who choose to associate with foreign nationals.

FURTHER CRACKS IN THE GLOBAL WARMING PROPHECY

Although global warming zealots continue their religious crusade, more research reveals skepticism toward the doomsday prophecies. Recently Finnish scientists published research that further debunks claims about the role of humans in generating global warming. Their thesis is that global temperatures are controlled primarily by cloud cover, which is a natural occurance that is beyond human control:

https://www.ecology.news/2019-07-12-climate-change-hoax-collapses-new-science-cloud-cover.html

The opponents immediately denounced this as a junk science:

It is OK and normal to have debates within scientific community. We, regular lay tax paying people are understandably not shrewd in all intricacies of scientific debates around so-called climate change. Yet, I am sure many of us want to make sure that no financially ruinous global or nationwide social engineering scheme would be enforced on all of us by social activists who decided to side with a group of aggressive academic zealots claiming scientific consensus and squashing dissenting views.

In his Counterrevolution of Science (1955), F. A. Hayek wrote about the dangerous hubris of “science worshippers” who wanted to extend their theories, which at best had narrow application and limited experimental database, to reshape the life of entire humankind. The first aggressive spearheads of this hubris were “generation X” socialists, acolytes of Henri St. Simone, who congregated in and around Paris Ecole Politechnique from the 1810s to 1860s. They dreamed about New Christianity – a creed based on the religion of science. With its “Council of Newton,” it was to regulate entire life of society. In the past century, we already lived through projects designated to reshape the life of humanity through “scientific” societal laws peddled by Marxism. We also lived through national socialist attempts to breed the better race of human beings based on “scientific” laws. More recently, in the 1970s, driven by the same scientific hubris backed by moral considerations, we resorted to global ban of “evil” DDT. This led to the outbursts of yellow fever and mass deaths in the Third World.

During a brief period of soul searching and self-scrutinizing among the left in the wake of communism collapse in the 1990s, in his Seeing Like a State (1998), James Scott, a leftist academic, gave a severe critique of that hubris that he called high modernism arrogance. Not naming socialism directly and sparing the ideological feelings of his fellow comrades, who have been dominating humanities and social sciences, he subtitled his book as follows How Certain Schemes to Improve the Human Condition Have Failed. Still, it was a devastating accusation of the “science”-based social engineering, from German attempts to breed perfect healthy forests in the 18th century to the “scientific socialism” of the Soviets who methodically ruined Russian agriculture by their aggreesive collectivization. The current left are not as modest as Scott’s generation. They quickly moved on, sweeping their own history under the rug. Being emboldened by the crisis of 2008 (a new “sign” of capitalism end of times), the left are now ecstatic about the Green New Deal and its Stalinist global warming regulations that are peddled by the big-eyed “democratic” socialist of “color” from Congress. It seems we are invited again to step on the same rake in order to smash our forehead once again by adopting another scientific Utopia.

Nightcap

- Not In My Backyard and “Buy Local” hypocrites Farhad Manjoo, New York Times

- Why the American Left should not go socialist Joseph Stiglitz, Foreign Policy

- Who was Maxwell Taylor? (Cold War) Gregory Daddis, War on the Rocks

- The lure of Western Europe Anne Applebaum, New York Review of Books

Poverty Under Democratic Socialism — Part III: Is the U.S. Denmark?

The Americans who call themselves “socialists,” do not, by and large, think in terms of government ownership of the means of production. Their frequent muted and truncated references to Sweden and Denmark indicate instead that they long for a high guarantees, high services state, with correspondingly high taxation (at least, for the more realistic among them).

When I try to understand the quasi-programmatics of the American left today, I find several axes: End Time-ism, a penchant for demanding that one’s collective guilt be dramatically exhibited; old-style pacifism (to an extent), a furious envy and resentment of the successful; indifference to hard facts, a requirement to be taken care of in all phases of life; a belief in the virtuousness and efficacy of government that is immune to all proof, demonstration, and experience. All this is often backed by a vigorous hatred of “corporations,” though I guess that not one in ten “progressives” could explain what a corporation is (except those with a law degree and they often misuse the term in their public utterances).

I am concerned that the last three features – nonchalance about facts, the wish to be cared for, and belief in government – are being woven together by the American left (vaguely defined) into what looks like a feasible project. I think that’s what they mean when they mention “democratic socialism.” The proponents seem to know no history. They are quick to dismiss the Soviet Union, currently foundering Venezuela, and even scrawny Cuba, as utterly irrelevant (though they retain a soft spot for the latter). And truly, those are not good examples of the fusion of socialism and democracy (because the latter ingredient was and is lacking). When challenged, again, American proponents of socialism refer vaguely to Sweden and to Denmark, about which they also seem to know little. (Incidentally, I personally think both countries are good societies.)

The wrong models of democratic socialism

Neither Sweden nor Denmark, however, is a good model for an eventual American democratic socialism. For one thing, the vituperative hatred of corporations on the American left blocks the path of economic growth plus re-distribution that has been theirs. In those two countries, capitalism is, in fact, thriving. (Think Ikea and Legos). Accordingly, both Sweden and Denmark have moderate corporate tax rates of 22% (same as the new Trump rate), higher than the German rate of only 16%, but much lower than the French rate of 34%.

The two countries pay for their generous welfare state in two intimately related ways. First, their populace agrees to high personal income taxes. The highest marginal rates are 60+% in Denmark and 57+% in Sweden. (It’s 46% currently in the US.) The Danes and the Swedes agree to such high rates for two reasons. For one thing, these rates are applied in a comparatively flat manner. Everyone pays high taxes; the rich are not publicly victimized. This is perceived as fair (though possibly destructive to economic growth). For another thing, their governments deliver superb social services in return for the high taxes paid.

This is the second way in which Danes and Swedes pay for their so-called “socialism” (actually welfare for all): They trust their government and the associated civil services. They generally don’t think of either as corrupt, or incompetent, as many, or at least a large minority of Americans do. As an American, I think of this trust as a price to pay. (I am not thinking of gross or bloody dictatorship here but more of routine time-wasting, exasperating visits to the Department of Motor Vehicles.) The Danes and the Swedes, with a different modern experience, do not share this revulsion or this skepticism.

Denmark and Sweden are both small countries, with populations of fewer than six million and about ten million, respectively. This means that the average citizen is not much separated from government. This short power distance works both ways. It’s one reason why government is trusted. It makes it relatively easy for citizens’ concerns to reach the upper levels of government without being distorted or abstracted. (5) The closeness also must make it difficult for government broadly defined to ignore citizens’ preoccupations. Both counties are, or were until recently, quite homogeneous. I used to be personally skeptical of the relevance of this matter, but Social-Democrat Danes have told me that sharing with those who look and sound less and less like your cousins becomes increasingly objectionable over time.

In summary, it seems to me that if the American left – with its hatred of corporations – tries to construct a Denmark in the US, it’s likely to end up instead with a version of its dream more appropriate for a large, heterogeneous county, where government moreover carries a significant defense burden and drains ever more of the resources of society. The French government’s 55% take of GDP is worth remembering here because it’s a measure of the slow strangling of civil society, including in its tiny embodiments such as frequenting cafés. In other words, American democratic socialists will likely end up with a version of economically stuck, rigid, disappointing France. It will be a poor version of France because a “socialist” USA would not have a ready-made, honest, elite corps of administrators largely sharing their view of the good society, such as ENA, that made the unworkable work for a good many years. And, of course, the quality of American restaurant fare would remain the same. The superior French gourmet experience came about and is nurtured precisely by sectors of the economy that stayed out of the reach of statism.

Poverty under democratic socialism is not like the old condition of shivering naked under rain, snow, and hail; it’s more like wearing clothes that are three sizes too small. It smothers you slowly until it’s too late to do anything.

(5) When there are multiple levels of separation between the rulers and the ruled, the latter’s infinitely variegated needs and desires have to be gathered into a limited number of categories before being sent up to the rulers for an eventual response. That is, a process of generalization, of abstraction intervenes which does not exist when, for example, the apprentice tells his master, “I am hungry.”

[Editor’s note: Part I can be found here, Part II here, and the entire, longform essay can be read in its entirety here.]

Poverty Under Democratic Socialism — Part II: Escaping the Padded Cage

There aren’t many signs that the French will soon free themselves from the trap they have sprung on themselves. The Macron administration had been elected to do something precisely about the strangling effect of taxation on French economic life and, on individual freedom. (The latter message may have been garbled during his campaign.) Are there any solutions in sight for the French crisis of psychic poverty, framed by both good social services and high taxes?

I see two kinds of obstacles to reform. The first is comprised of collective cognitive and of attitudinal deficiencies. The second, paradoxically, is a feature of French society that American progressives would envy if they knew about it.

Cognition and attitudes

After four months of weekly demonstrations, the gilets jaunes (“yellow vests”) protesters had not found the language to articulate clearly their frustration. I mean, at least those who were left protesting. They seem to be falling back increasingly on crude views of “social justice” (“les inégalités”) as if, again, the issue was never to produce more, or to retain more of what they produce, but only to confiscate even more from the (fleeing) rich. Over the many years of democratic socialism, French culture has lost the conceptual vocabulary that would be necessary to plan an exit out of the impasse. Here is an example of this loss: In the past twenty years of reading and watching television in French almost every day, I have almost never come across the single word “libéral.” (That would be in the old English meaning of “market oriented.”) The common, nearly universal term is “ultra-libéral.” It’s as if favoring an analysis inclined toward market forces could not possibly exist without being “ultra,” which denotes extremism.

What started as a fairly subtle insult against those who discreetly appreciate capitalism has become fixed usage: You want more free market? You are a sort of fanatic. This usage was started by professional intellectuals, of course (of which France has not shortage). Then, it became a tool tacitly to shut off certain ideas from the masses, all the while retaining the words derogatory muscle. So, in France today, one can easily think of oneself as a moderate socialist – on the center left – but there is no balancing position on the center right. (3) It makes it difficult to think clearly, and especially to begin to think clearly about politics. After all, what young person wants to be an extremist, except those who are really extremists?

I saw recently online a French petition asking that French economist Frédéric Bastiat’s work be studied in French schools. Bastiat is one of the clearest exponents of fundamental economics. His contribution is not as large or as broad as Adam Smith’s but it’s more insightful, in my judgment. (He is the inventor of the “broken window” metaphor, for instance.) He also wrote unusually limpid French. Bastiat has not been part of secondary studies in France in my lifetime. His name is barely known at the university level. Marx and second, and third-rate Marxists, on the other hand, are omnipresent. (Some cynics would claim that whatever their conversation, the educated French do not read Bastiat, or A. Smith, but neither do they really read Marx!)

Few, in France, are able to diagnose the malaise that grips the country because it has ceased to have a name. The handful who understand capitalism are usually allergic to it because it does not guarantee equal outcomes. A minority, mostly business people, grasp well enough how it works and how it has pulled most of humanity out of poverty but they are socially shamed from expressing this perception. There is little curiosity among the French about such questions as why the American GDP/capita is 35% higher than the French. They treat this information as a sort of deed of Nature. Or, for the more ideological, among them, it’s the sad result of America’s unfairness to itself. A debate that ought to take place is born dead. How did this happen? Socialists of my generation, most good democrats, born during and right after WWII largely, early on took over the media and the universities. They have shaped and constrained public opinion since at least the sixties. They have managed to stop discussions of alternative economic paths without really conspiring to do so, possibly without even meaning to.

A really deep state

In 1945, after the long night of the 1940 defeat and of the Nazi occupation, many French people where in a mood to engender a new society. They created a number of novel government organizations designed to implement their vision of clean government but also, of justice. (They took prosperity for granted, it seems.) One of the new organizations was a post-graduate school especially designed to ensure that access to the highest levels of the government bureaucracy would be democratic and meritocratic. It’s called, “École Nationale d’Administration” (ENA). It accepts only graduates of prestigious schools. The ENA students’ per capita training costs are about seven times the average cost for all other higher education students. ENA students are considered public servants and they receive a salary. France thus possesses a predictably renewed cadre of trained administrators to run its government. And, repeating myself here, its members are chosen according to a strictly meritocratic process (unlike the most prestigious American universities, for example), a process that is also extremely selective.

In 2019, ENA is flourishing. The school has contributed four presidents and eight Prime Ministers to-date. Its graduates are numerous among professional politicians, as you might expect. In addition, they are teeming in the highest ranks of the civil service, and also of business. That’s because they go back and forth between the two worlds, with some benefit to their careers and to their wallets. This iteration does not imply corruption. Mostly, ENA graduates do not have a reputation for dishonesty at all. They help one another but it’s mostly above board. (4) This being said, it’s difficult to become really poor if you are an ENA graduate.

Graduates of ENA are often disparagingly described as a “caste,” which is sociologically inaccurate because caste is inherited. The word is meant to render a certain collective attitude of being smugly sealed from others. The intended meaning is really that of “upper caste,” of Brahman caste, to signify: those who think they possess all the wisdom.

All ENA graduates have made it to the top by taking the same sort of exam. The style of exams and the way they are corrected become known over time. Naturally, ENA candidates study to the exam. The ENA formula for success is not a mystery although it’s not just a formula; ENA also requires a sharp intelligence and character. ENA graduates have important traits in common, including a willingness to spend their adolescence cramming for increasingly difficult competitive exams. There are few charming dilettantes in their ranks. They all emerge from a process that does not reward imagination.

ENA graduates – dubbed “énarques” – seem overwhelmingly to share a certain view of the desirable interface between government and the economy. It’s not hard to guess at, based on thousands of their speeches reproduced in the media, and with the help of a little familiarity with French classical education. Its origin is neither in capitalism nor in socialism. (Sorry for the only slightly misleading title of this essay.) It predates both by 100-150 years. It’s rooted in the well known story of the Minister Colbert’s 17th century economic reforms. (It’s well known in the sense that every French school kid knows his name and a thing or two about the reforms themselves.) Colbert (1619-1683) raised tariffs, regulated production in minute detail and, above all, he created with public funds whole industries where none existed, in glass, in porcelain, but also in textiles, and others. I believe his main aim was only to increase government (royal) revenue but others think differently. At any rate, there is a widespread belief that general French prosperity rose under his administration.

To make matters worse, Colbert is a historical figure easy to like: hard working, honest, an effective patron of the arts. With such a luminary to look up to, it’s fairly effortless to ignore both the actual disorderly origins of capitalism, and also the initially compassionate roots of its socialist counter-reaction. (On capitalism’s origins, and originality, you might consult my entry: “Capitalism.” The Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology. Blackwell Publishing. Vol. 2, Malden, Mass. 2006. Make sure of that particular edition – 2006 – my predecessors and successors were mostly opaque Marxist academic lowlifes.)

For seventy years, French economic policy has thus been made largely by deeply persuaded statists, people who think rule from above natural (especially as it takes place within a broadly democratic framework), who judge government intervention in economic matters to be necessary, fruitful, and virtuous, people who believe that government investment is investment, people who have given little thought to private enterprise, (although they occasionally pay lip service to it, largely as if it were a kind of charity). Almost none of them, these de facto rulers, is a bad person. Their pure hearts make them all the more dangerous, I believe. The result is there in France for all to see: a sclerotic economy that has failed to provide enough jobs for fifty years, a modest standard of living by the criteria of societies that industrialized in the nineteenth century, a worsening unease about the future, a shortage of the freedom of small pleasures for the many.

I do not use the conventional words of “tyranny” or “despotism” here because both are normally more less deliberately imposed on the populace. Nothing of the sort happened in France. On the contrary, lack of individual freedom in France is the accumulated consequence of measures and programs democratically adopted within the framework described above. Together, these well-meaning social programs are squeezing the liveliness out of all but the upper layers of French society.

There exists in the country a growing resentment of the énarques’ basically anti-capitalist rule. One recent president, Sarkozy, even declared he partly owed his election to bragging about not being a graduate from ENA. Yet, the thousands of énarques permanently at the levers of command for seventy years are not about to relinquish them, irrespective of the political party or parties in power. Few groups controlling as much as they ever does so voluntarily. The deep sentiment of their collective virtuousness will make them even more intransigent. Most French critics believe that the énarquesare incapable of changing as a cadre, precisely because they are really an intellectual elite of sorts, precisely because they are not corrupt. And, as I remarked above, ENA’s statist (“socialist”) reign has lasted so long that the French people in general have lost track of the very conceptual vocabulary an anti-bureaucrat rebellion would require. (We know what we don’t want, but what do we want?)

(3) It’s true also that historical accidents have deprived France of a normal Tory party. Its place is currently occupied by reactionary nationalists (currently the “Rassemblement national,” direct descendant of the “Front National,” of Marine Le Pen) who don’t favor market forces much more than does the left.

(4) I take the ENA graduates’ reputation for probity seriously because, right now, as I write, there are clamors for abolishing the school but its generating corruption in any way is not one of the reasons advanced.

[Editor’s note: Here is Part I, and here is the entire longform essay.]

Poverty Under Democratic Socialism — Part I: the French Case

I saw a televised investigation by the pretty good French TV show, “Envoyé spécial” about current French poverty. It brought the viewer into the lives of six people. They included a retired married couple. The four others were of various ages. They lived in different parts of mainland France. All sounded French born to me. (I have a good ear for accents; trust me.) All were well spoken. The participants had been chosen to illustrate a sort of middle-class poverty, maybe. Or, perhaps to illustrate the commonness of poverty in one of the first countries to industrialize.

All the interviewees looked good. They seemed healthy. None was emaciated; none was grossly obese, as the ill-fed everywhere often are. All were well dressed, by my admittedly low standards. (I live in the People’s Democratic Republic of Santa Cruz, CA where looking dapper is counter-revolutionary.) None of those featured was in rags or wearing clothes inappropriate for the season.

The reporter took the viewer into these people’s homes. There was no indoor tour but you could see that the outside of the houses was in good repair. Most of the interviewing took place in kitchens. Every kitchen seemed equipped like mine, more than adequately. There was a range and a refrigerator in each. Every house had at least one television set.(I couldn’t determine of what quality.) No one said he or she was cold in the winter though two complained about their heating bills.

The show was geared to sob stories and it got them. Each participant expressed his or her frustration about lacking “money,” precisely, specifically. It seems to me that all but two talked about money for “extras.” I am guessing, that “extras” mean all that is not absolutely necessary to live in fairly dignified comfort. One single woman in her forties mentioned that she had not had a cup of coffee in a café for a year or more. (Keep her in mind.)

Another woman talked about the difficulty of keeping her tank filled. She remarked that a car was indispensable where she lived, to go to her occasional work and to doctors’ appointments. Her small car looked fine in the video. The woman drove it easily, seemingly without anxiety or effort.

A woman of about forty, divorced, took care of her two teenage daughters at home two weeks out of each month. She explained how she went without meat for all of the two weeks that her daughters were away. She did this so she could afford to serve them meat every day that they were with her. I could not repress the spontaneous and cynical reaction that most doctors would probably approve of her diet.

Yet, another woman, single and in her thirties, displayed her monthly budget on her kitchen table. She demonstrated easily that once she had paid all her bills, she had a pathetically small amount of money left. (I think it was about $120 for one month.) She had a boyfriend, a sort of good-looking live-in help whose earnings, if any, were not mentioned.

The retired couple sticks to my mind. The man was a retired blue-collar worker. They were both alert and in good shape. Their living room was comfy. They also talked about their bills – including for heating – absorbing all of their income. The wife remarked that they had not taken a vacation in several years. She meant that she and her husband had not been able to get away on vacation, somewhere else, away from their house and from their town. They lived close to a part of France where some rich Americans dream of retiring some day, and where many Brits actually live.

I ended up a little perplexed. On the one hand, I could empathize with those people’s obvious distress. On the other hand, I got yanked back to reality toward the end when the retired lady blamed the government for the tightness of her household budget. Then I realized that others had tacitly done the same. The consensus – which the reporter did not try expressly to produce – would have been something like this: The government should do something for me (no matter who is responsible for the dire straights I am in now).

Notably, not one of the people in the report had a health care complaint, not even the senior retired couple.

So, of course, I have to ask: Why are all those people who live far from abject poverty, by conventional standards, why do all those people convey unhappiness?

The first answer is obvious to me only because I was reared in France, where I retain substantial ties: Many small French towns are dreadfully boring, always have been. That’s true, at least, if you don’t fish and hunt, or have a passion for gardening, and if you don’t attend church. (But the French are not going to church anymore; nothing has taken the social place of church.)

And then, there is the issue of what the French collectively can really afford. This question in turn is related to productivity and, separately, to taxation. I consider each in turn.

French productivity

According to the most conventional measure – value produced per hour worked – French productivity is very high, close to the German, and not far from American productivity: Something like 93% of American productivity for the French vs 95% for the Germans. (Switzerland’s is only 86%.) However, to discuss how much money is available for all French people together, we need another measure: the value of French production divided by the number of French people. Annual Gross Domestic Product per capita is close enough for my purpose. (The version I use is corrected to incorporate the fact that the buying power of a dollar is not the same in all countries: “GDP/capita, Purchasing Power Parity”).

For 2017, the French GDP/capita was $43,600, while the German was $50,200. (The American was $59,500.) Keep in mind the $6,600 difference between the French and the German GDP/capita (data).

If French workers are almost as productive as the Germans when they work, what can account for the low French GDP/capita? The answer is that the French don’t work much. Begin with the 35/hr legal work week. (1) (A study published recently in the daily Le Figaro asserts that 1/3 of the 1.1 million public servants work even less than 35 hours per week.) Consider also the universal maximum retirement age of 62 (vs 67 in Germany), a spring quarter pleasantly spiked with three-day weekends for all, a legal annual vacation of at least thirty days applied universally, a common additional (short) winter (snow) vacation. I have read (I can’t confirm the source) that the fully employed members of the French labor force work an average of 600 hours per year, one of the lowest counts in the world. Also log legal paid maternity leave. Finish with an official unemployment rate hovering around 9 to 10% for more than thirty years. All this, might account for the $6,600 per year that the Germans have and the French don’t.

There is more that is seldom mentioned. The fastest way for a country to raise the official, numerical productivity of its workers is to put out of work many of its low-productive workers. (That’s because the official figure is an arithmetic mean, an average.) This can be achieved entirely through regulations forbidding, for example, food trucks, informal seamstress services, and old-fashioned hair salons in private living rooms, and, in general, by making life less than easy for small businesses based on traditional techniques. This can be achieved entirely – and even inadvertently – from a well-meaning wish to regulate for the collective good. The more of this you do, the higher your productivity per capita appears to be and also, the higher your unemployment, and the less income is available to go around. I think the official high French productivity oddly distorts the image of real French income. I suspect it fools many French people, including public officials: They think they are wealthier than they are.

La vie est belle!

The French have nearly free health care – which works approximately as well as Medicare in the USA, well enough, anyway. (French life expectancy is higher than American expectancy.) Education is tuition-free at all levels. There are free school lunches for practically anyone who asks. University cafeterias are subsidized by the government (and pretty good by, say, English restaurant standards!) Many college students receive a stipend. Free drop-off daycare centers are common in big and in medium-size cities. Unemployment benefits can easily last for two years, three for older workers. They amount to something like 55% of the last wages earned, up to 75% for some.

That’s not all. The fact that France won the World Cup in soccer in 2018 suggests that the practice of that sport is widespread and well supported. It’s mostly government subsidized. Other sports are also well subsidized. French freeways are second to none. They are mostly turnpikes but the next network of roads down is excellent, and even the next below that. This is all kind of munificent, by American standards. The French are taken care of, almost no matter what. The central government handles nearly all of this distribution of services directly and some, indirectly through grants that local entities have to beg for.

Someone has to pay for all this generosity. After sixty or seventy years, many, perhaps most French people, still believe that the rich, the very rich, have enough money that can be pried from their clutching hands to pay for the good things they have, plus the better things they wish for. (No hard numbers here, but I would bet that ¾ of French adults believe this.) In fact, multi-fingered, ubiquitous, invasive taxation of the many who are not very rich pays for all of it.

French taxation

The French value added tax (VAT) is 20% on nearly all transactions. When a grower sells $100 of apples to a jelly producer, the bill comes to $120. When the jelly-maker in turn sells his product to a grocery wholesaler, his $200 bill goes up to $240, etc. Retail prices are correspondingly high. The French are not able to cheat all the time on the VAT although many try. (Penalties are costly on the one hand, but there exists a complicated, frustrating official scheme to get back part of the VAT you do pay, on the other hand.) I speculate that the VAT is so high because the French state does not have the political will nor the capacity to collect an effective, normal income tax, a progressive income tax. Overall, the French fiscal system is not progressive; it may be unintentionally regressive. To compensate, until the Macron administration, there was a significant tax on wealth. (That’s double taxation, of course.) It’s widely believed that rich French people are escaping to Belgium, Switzerland, and even to Russia (like the actor Gérard Dupardieu).

The excise taxes are especially high, including the tax on gasoline. In 2018, the mean price of gasoline in France was about 60% higher than the mean price in California, where gas is the most taxed in the Union. An increase to gasoline taxes, supposedly in the name of saving the environment, is what triggered the “yellow vests” rebellion in the fall of 2018. Gasoline taxes are particularly regressive in a country like France where many next-to-poor people need a car because they are relegated to small towns, far from both essential services and work. (2)

All in all, the French central government takes in about 55% of the GDP. This may be the highest percentage in the world; it’s very high by any standard. It dries up much money that would otherwise be available to free enterprise. Less obviously but perhaps more significantly, it curtails severely what people individually, especially, low income citizens, may spend freely, of their own initiative.

What’s wrong?

So, with their abundant and competent social services, with their free schooling, with their prodigal unemployment benefits, with their superb roads, with their government-supported prowess in soccer, what do the French people in the documentary really complain about? Two things, I think.

Remember the woman who couldn’t afford to take her coffee in a café? Well, the French have never been very good at clubs, associations, etc. They are also somewhat reserved about inviting others to their homes. The café is where you avail yourself of the small luxury of avoiding cooking chores with an inexpensive but tasty sandwich. It’s pretty much the only place where you can go on the spur of the moment. It’s where you may bump into friends and, into almost-friends who may eventually become friends. It’s the place where you may actually make new friends. It’s the best perch from which to glare at enemies. It’s where that woman may have a chance to overhear slightly ribald comments that will make her smile. (Not yet forbidden in France!) The café is also just about the only locale where different age groups bump into one another. The café is where you will absorb passively some of that human warmth that television has tried for fifty years but failed to dispense.

This is not a frivolous nor a trivial concern. In smaller French towns, a person who does not spend time in cafés is deprived of an implicit but yet significant part of her humanity. The cup of coffee the woman cannot afford in a café may well be the concrete, humble, quotidian expression of liberty for many in other developed countries as well. (After all, Starbucks did not succeed merely by selling overpriced beverages.) The woman in the video cannot go to cafés because the social services she enjoys and supports – on a mandatory basis – leave no financial room for free choice, even about tiny luxuries. She suffers from the consequences of a broad societal pick that no one forced on her. In general, not much was imposed on her from above that she might have readily resisted. It was all done by fairly small, cumulative democratic decisions. In the end, there is just not enough looseness in the socio-economic space she inhabits to induce happiness.

She is an existential victim of what can loosely be called “democratic socialism.” It’s “democratic” because France has all the attributes of a representative republic where the rule of law prevails. It’s “socialistic” in the vague sense in which the term is used in America today. Unfortunately, there is no French Bureau of Missing and Lost Little Joys to assess and remedy her discontent. Democratic socialism is taking care of the woman but it leaves her no elbow room, space for recreation, in the original meaning of the word: “re-creation.”

The second thing participants in the documentary complain about is a sense of abandonment by government. Few of them are old enough to remember the bad old days before the French welfare state was fully established. They have expected to be taken care of all their adult lives. If anything is not satisfactory in their lives, they wait for the government to deal with it, even it takes some street protests. Seldom are other solutions, solutions based on private initiative, even considered. But the fault for their helplessness lies with more than their own passive attitudes. An overwhelming sense of fairness and an exaggerated demand for safety combine with the government’s unceasing quest for revenue to make starting a small business, for example, difficult and expensive. France is a country where you first fill forms for permission to operate, and then pay business taxes before you have even earned any business income.

The French have democratically built for themselves a soft cradle that’s feeling more and more like a lead coffin. It’s not obvious enough of them understand this to reverse the trend, or that they could if they wished to. There is also some vague worry about their ability to maintain the cradle for their children and for their children’s children.

(1) I am aware of the fact that there exists a strong inverse correlation between length of week worked and GDP/capita: In general, the richer the country, the shorter the work week. Again, this is based on a kind of average. It allows for exceptions. It seems to me the French awarded themselves a short work week before they were rich enough to afford it.

(2) You may wonder why I don’t mention the French debt ratio (amount of public debt/GDP). All the amenities I describe must cost a lot of money and the temptation to finance them partly through debt must be great. In fact, the French debt ratio is lower than the American: 96% to 109% in 2018 according to the International Monetary Fund. This is a little surprising but all debtors are not equal. A country with near full employment and plenty of talent is better able to pay off its debts than one with high long term unemployment and a labor force decreasingly accustomed to laboring. The latter is, of course, a predictable result of inter-generational unemployment and underemployment. Nowadays, it’s common to cross paths in France with people over thirty who have never experienced paid work. International investors think like me about the inequality of debtors. Investors flock to the US but they are reserved about France.

[Editor’s note: You can find the entire, longform essay here if you don’t want to wait for Parts II and III.]

John Rawls had good reason to be a reticent socialist and political liberal

John Rawls: Reticent Socialist by William A. Edmundson has provoked a renewed attempt, written up in Jacobin and Catalyst, to link the totemic American liberal political philosopher with an explicitly socialist program to fix the problems of 21st century capitalism, and especially the domination of the political process by the super-rich. I found the book a powerful and enlightening read. But I think it ultimately shows that Rawls was right not to weigh his philosophy down with an explicit political program, and that socialists have yet to respond effectively to James Buchanan’s exploration of the challenges of non-market decision-making – challenges that bite more when states take on more explicit economic tasks. The large-scale public ownership of industry at the core of Edmundson’s democratic socialism is plausibly compatible with a stable, liberal political community in some circumstances but it is unclear how such a regime is supposed to reduce the scope of social domination compared with a private-property market economy in similar circumstances once we look at public institutions with the same skeptical attention normally reserved for private enterprise. A draft review is below.

Nightcap

- Sexual Harassment’s Legal Maze Rachel Lu, Law & Liberty

- Why the argument for democracy may finally be working for socialists rather than against them Corey Robin, Crooked Timber

- How much value does the Chinese government place on freedom? Scott Sumner, EconLog

- Authoritarian Nostalgia Among Iraqi Youth Marsin Alshamary, War on the Rocks