Yesterday, the Catalan government has overwelmingly voted for independence from Spain and to establish an independent republic. 70 were in favour, 10 were against, and 2 votes were blank. Unfortunately, it was rejected by the central governments of Spain and many other countries. Nonetheless, the Catalan case may inspire the other independence movements in Europe.

In this post I’d like to provide a philosophical case for the ethical right of secession based on a libertarian perspective of self-ownership. My argument is exclusively theoretical, although a discussion on how secession could be achieved practically would be interesting as well. I may save that for a post in the future.

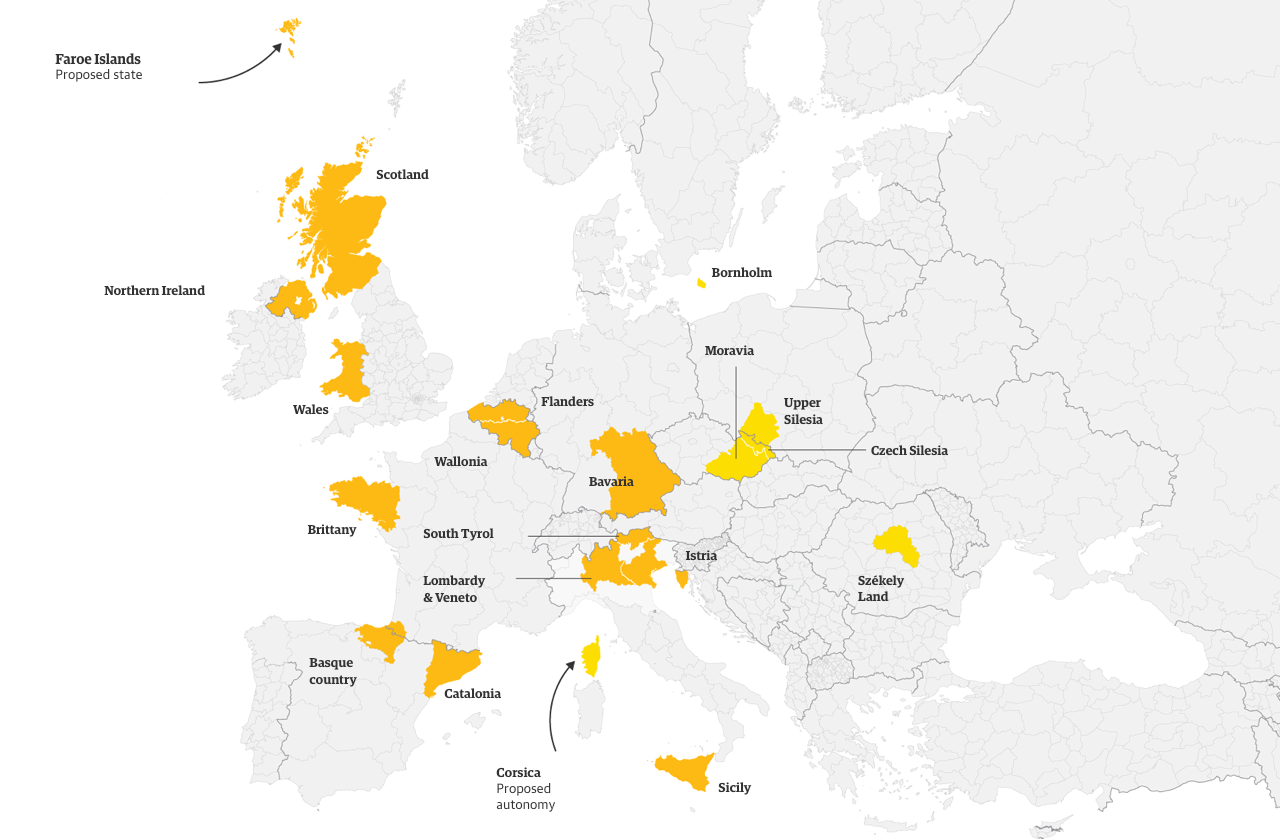

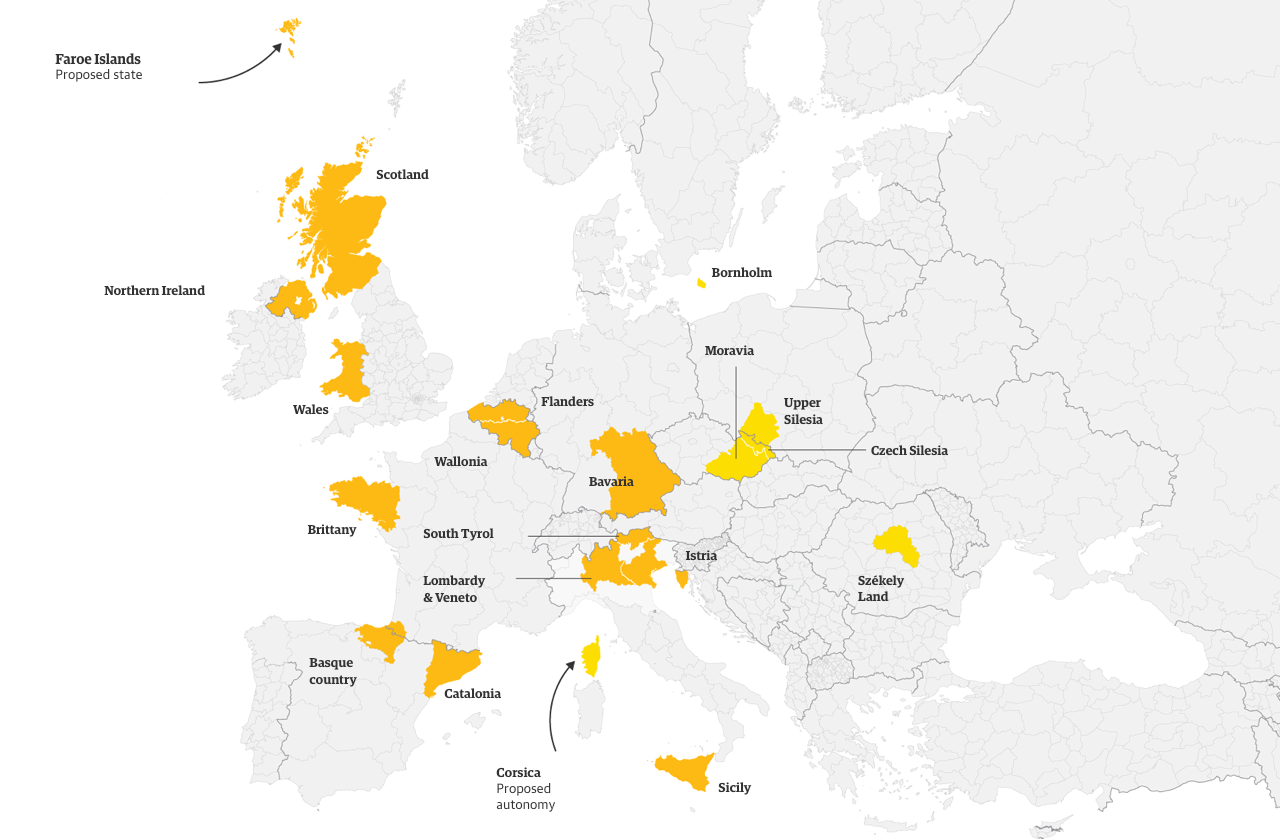

Below, you can find a map of other places in Europe with strong secessionist movements:

Structure of my argument

My argument is deductive and runs as follows:

- People have the right of self-ownership in accordance with the non-aggression principle, and based on the natural rights philosophy put forward by the political philosopher Murray Rothbard;

- If people have the right of self-ownership, they also have the right of voluntary association, voluntary formation of communities, and the right to choose their own leaders;

- Sometimes the state that the individual belongs to, violates the rights of the individual to the extent that the individual does not feel associated with it anymore;

- Under such circumstances the individual may perceive the state as an unacceptable aggressor, and he is justified to revolt by separating himself from the state. He can form communal associations to secede as a new political unit;

- There is no limit to secession. Provinces have the right to secede from a state, a district from the province, a town from the district, a neighbourhood from the town, a household from the neighbourhood, and an individual from the household.

The right of self-ownership and property rights

In For a New Liberty (1973), Murray Rothbard deduces natural law from the essential nature of human beings. He writes that it is in man’s nature to use his mind in order to select values, ends and the means to attain these ends so that he can “act purposively to maintain himself and advance his life”. He furthermore contends that it is absolutely “antihuman” to interfere violently with a man’s “learning and choices” as “it violates the natural law of man’s needs”. Therefore, man’s nature should be protected through his right of self-ownership. This right asserts that man has the absolute right to “own” his body and “to control that body free of coercive interferences”. This right includes the practice of such essential activities as thinking, learning, valuing, and choosing ends and means without any coercion, since such activities are necessary for the enhancement of man’s life.

From this natural right follows the right to do anything with one’s body, including the right to form free associations and communities, and the right not to be violated in one’s self-ownership. Thus, one has the right to associate oneself with the leader of one’s choice, but not the right to impose a leader unto someone else. Likewise, people should be free to join and to leave communities voluntarily.

In addition to the right of free association, people also have property rights. Rothbardian property rights are directly derived from self-ownership rights, and are based on the Lockean homesteading theory. It states that since man owns his person, he owns his labour, and therefore he also owns the fruits thereof. John Locke (1689) has put homesteading theory in the following way:

… every man has a property in his own person. … The labour of his body and the work of his hands, we may say, are properly his. Whatsoever, then, he removes out of the state of nature hath provided and left it in, he hath mixed his labour with it, and joined it to something that is his own, and thereby makes it his property.

Given that man has the right of self-ownership, and that he must employ natural objects for his survival, then the sculptor has the right to own the product he has made through the mixing of his labour. In other words, by producing something with one’s energy through the utilization of unowned nature, one has, as Rothbard calls it, “placed the stamp of his person upon the raw material”. One therefore rightfully owns the product. Any violation of self-ownership and property rights should hence be regarded as an act of aggression.

The state

The state is nonetheless a social institution that has historically interfered most often with people’s self-ownership and property rights. Max Weber has recognized it as an institution with a territorial monopoly of compulsion in his essay ‘Politics as a Vocation’ (1919). Hoppe, in Democracy – the God that failed (2001), asserts that every government will use this monopoly to exploit its citizens in order to increase its wealth and income.

“Hence every government should be expected to have an inherent tendency toward growth”. (Hoppe)

State exploitation happens in the form of expropriation, taxation, and regulation of private property owners. A state at best respects the rights of individual sovereignty and private property, but because its functioning is dependent on the expropriation of its citizens’ wealth there is a natural conflict between the state and its citizens. According to Franz Oppenheimer (1908), the state can impossibly finance itself without its productive citizens. It can only take that what has already been produced, and therefore it can only exist as a result of the “economic means”. However, this confiscation often involves state violence and aggression as nearly no one is willing to give up on his property voluntarily.

Under such circumstances, it is understandable that conflicts may arise between citizens and the state; sometimes resulting in citizens’ feelings of dissociation from their governments.

Secession

Frédérik Bastiat maintains in The Law (1850) that if everyone has the right to “his person, his liberty, and his property”, then

“a number of men have the right to combine together to extend, to organize a common force to provide regularly for this defense.”

Following Bastiat’s reasoning, I believe that citizens who feel dissociated can then revolt and opt for secession as a form of self-defense against state aggression on their self-ownership and property. Any state that does not recognize its citizens’ rights of secession does not sufficiently recognize the sovereignty of its people. Secession is a powerful means of political action to show the people’s discontent with their leaders. If secession would be impermissible, then the people who want to disassociate themselves from the state have the following three options:

(1) continue living under the oppressive state rule;

or (2) revolt against the state;

or (3) emigrate to another state.

By doing (1), the people continue living under perpetual state aggression, and their sovereignty is continually violated.

If the people choose option (2), then there will be severe and costly consequences which can involve war and destruction of private property. In addition, there are also no guarantees that the revolt against the state will be successful. For these two reasons, this option seems to most secessionists to be the least preferable of the three.

The people can alternatively choose (3) and emigrate to another state. This alternative is often used as an argument against secession under the presumption that those who are unhappy within one particular state, should simply emigrate. However, the cost of emigration can be so significantly high that it is unfeasible. One has for example the costs of finding information on the procedure of emigration, becoming accepted by the other state, finding a new workplace etc… The state can also exert barriers of emigration through tedious bureaucratic processes and passport controls, which makes emigration even more unattractive.

Who are morally justified to secede?

Following man’s right of free association, the answer should be: anyone, as long as it happens on a voluntary basis. Even though most secessionist movements are built on a common ethnicity or common cultural heritage, such precepts are not necessary to justify secession. Moreover, secessionists should not be prescribed any form of social organization as they should be free to choose their own form of government. This means that a multitude of social organizations are possible, including those that are currently non-existent. By being epistemologically modest of what governmental form is best, communities are allowed to experiment and find their own form of government. This will eventually add to our understanding of human social organizations.

Lastly, it is important to note that if secession is ethical, ultimately based on the principle of self-ownership, then it follows that the individual has the right to secede as well.

This right cannot be exclusively granted to groups, because only individuals can have ownership of their own bodies. Self-ownership cannot be shared, just like the mind cannot be shared. The mind is an attribute, inherent only to individuals, and collectives only derive their rights from the rights of their individual members. Therefore the right of self-ownership must necessarily imply the right to practice unlimited secession.

As Rothbard would assert, provinces should have the right to secede from a state, a district from the province, a town from the district, a neighbourhood from the town, a household from the neighbourhood, and an individual from the household. This logical consequence is anarchism.

Conclusion

In setting forward a natural rights defense of self-ownership, I have concluded that individuals have the right to free association and property rights. Unfortunately, states sometimes violate these rights to the extent that its people do not want to be associated with their state anymore. Under such circumstances they retain the right to secede. Secession should however not only be limited to communities. Single individuals also bear the right to secede, since only individuals can possess self-ownership, and since groups can only derive their rights from its individual members.