Vestis virum (non) redit

~ Latin proverb

As Brexit drags on, there is a reassessment occurring of Margret Thatcher and her legacy. After all, in addition to being a stalwart defender of free markets, free enterprise, and free societies, she helped design the EEC, the precursor to the EU. So in the process of leaving the EU, there is a lingering question regarding whether the referendum is a rejection of Thatcher’s legacy. Those who equate the referendum with a repudiation of Thatcher offer explanations along the lines of: “Thatcher destroyed the miners’ way of life [NB: this is a retort spat out in a debate on the freedom-vs.-welfare split in the Leave faction; it has been edited for grammar and clarity.].” Sooner or later, Thatcher-themed discussions wend their way to the discontents of capitalism, especially the laissez-faire variety, in society, and the complaints are then projected onto issues of immigration, sovereignty, or globalism.

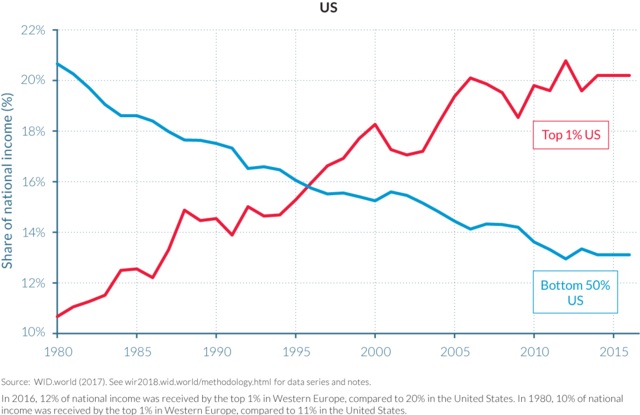

On the other side of the Atlantic, Tucker Carlson’s January 2 polemical monologue contained similar sentiments and provoked a response that proved that the same issues have divided America as well. Much of Carlson’s complaints were predicated on the concept of “way of life,” and here lies a dissonance which has meant that swaths of society talk without understanding: merely possessing a way of life is not equal to having values. In all the discussion of the “hollowing out of the middle-class,” one question is never raised: What is the middle-class?

It is only natural that no one wants to ask this question; modern society doesn’t want to discuss class in a real sense, preferring to rely on the trite and historically abnormal metric of income. To even bring up the C- word outside of the comfortable confines of money is to push an unspoken boundary. Although there is an exception: if one is speaking of high-income, or high-net-worth individuals, it is completely acceptable to question an auto-definition of “middle-class.” Everyone can agree that a millionaire describing himself as middle-class is risible.

It is the income dependent definition that is the source of confusion. The reality is that modernity has conflated having middle income with being middle-class. The two are not one and the same, and the rhetoric surrounding claims of “hollowing out” is truly more linked to the discovery that one does not equal the other.

In his The Suicide of the West, Jonah Goldberg wrote on the subject of the back history of the Founding Fathers:

[….] British primogeniture laws required that the firstborn son of an aristocratic family get everything: the titles, the lands, etc. But what about the other kids? They were required to make their way in the world. To be sure, they had advantages – educational, financial, and social – over the children of the lower classes, but they still needed to pursue a career. “The grander families of Virginia – including the Washingtons – were known as the ‘Second Sons,’” writes Daniel Hannan [Inventing Freedom: How the English-Speaking Peoples Made the Modern World (HarperCollins, 2013)]. [….]

In fact, Hannan and Matt Ridley [The Rational Optimist: How Prosperity Evolves (Harper, 2010] suggest that much of the prosperity and expansion of the British Empire in the eighteenth century can be ascribed to an intriguing historical accident. At the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, the children of the affluent nobility had a much lower mortality rate, for all the obvious reasons. They had more access to medicine, rudimentary as it was, but also better nutrition and vastly superior living and working conditions than the general population. As a result, the nobility were dramatically more fecund than the lower classes. Consequently, a large cohort of educated and ambitious young men who were not firstborn were set free to make their way in the world. If you have five boys, only one gets to be the duke. The rest must become officers, priests, doctors, lawyers, academics, and business men.

Goldberg concisely summarized the phenomenon which Deirdre McCloskey argues created the original middle-class. But more importantly, Goldberg’s history lesson emphasizes that the origins of America, from an idea to a reality, have a deep socio-cultural angle, one that is tied to status, property rights, and familial inheritance, that is often lost in the mythology.

As Goldberg explained, the complex, painful history of disenfranchisement due to birth order was the real reason the Founding Fathers both opposed the law of entail while simultaneously focusing almost myopically on private property rights in relation to land. As Hernando de Soto studied in his The Mystery of Capital, George Washington, who held land grant patents for vast, un-surveyed tracts in Ohio and Kentucky, was horrified to discover that early settlers had established homesteads in these regions, before lawful patent holders could stake their claims. Washington found this a violation of both the rule of law and the property rights of the patent holders and was open to using military force to evict the “squatters,” even though to do so would have been against English common law which gave the property to the person who cleared the land (Washington was no longer president at that point, so there was no risk that the aggressive attitude he expressed in his letters would lead to real action.).

Before repudiating Washington for his decidedly anti-liberty attitude on this score, we should turn to Deirdre McCloskey and her trilogy – The Bourgeois Virtues: Ethics for an Age of Commerce, Bourgeois Dignity: Why Economics Can’t Explain the Modern World, and Bourgeois Equality: How Ideas, Not Capital or Institutions Enriched the World – for an understanding on why this might be important, and why conflating way of life with social standing and identity is both fallacious and dangerous.

Part II coming soon!