A first in this series, a discussion of literary texts rather than a text covering political ideas through philosophical, historical, legal, or social science writing. One good reason for the new departure is simply that the sagas of Iceland have become a focus of debate about the possibility of a society with effective laws and courts, but no state.

It has become a celebrated case in some pro-liberty circles largely because of an article by the anarchy-capitalist/individualist anarchist libertarian thinker David Friedman (son of Milton) in ‘Private Creation and Enforcement of Law: A Historical Case’, though it has also been widely studied and sometimes at full book length by scholars not known for pro-liberty leanings. I somewhat doubt that Iceland of that era could be said to have purely private law, but I will let the reader judge from the descriptions that follow.

Other important things also come up in discussing the sagas. There is the issue of how much political ideas, political theory, or political philosophy just reside in written texts devoted to theories, institutions, and history, and how much they may reside in everyday culture, collective memory, and the literature of oral tradition. This becomes a particularly important issue when considering cultures lacking in written texts, but nevertheless has ethics, law, and juridical practice of some kind. The modern discipline of anthropology has provided ways of thinking about this, but rooted in older commentaries on non-literate societies, as in the Histories of Herodotus (484-425 BCE) and indeed the texts by Tacitus, considered here last week, on ancient Britons and Germans.

The Icelandic sagas present the ‘barbarians’ in their own words, though with the qualification that the sagas were largely from Pagan-era Iceland and then were written down in Christian-era Iceland. You would expect some alterations of a kind in the sagas as they are transferred from memory and speech to writing, and the religious transformation may have led to some element of condemnation of the old Pagan world colouring the transcription.

Nevertheless we have tales of Pagan warrior heroes in a society with very little in the way of a state, written down only a few centuries later (maybe three centuries), which is a lot closer in time than the absolute minimum of seven centuries between whatever events inspired the Homeric epics, the Iliad and the Odyssey, and the writing down of the oral tradition in the eighth century BCE.

The comparison with Homer is worth making, because the Sagas present warrior-heroes whose extreme commitment to the use of individual violence to maintain and increase status echoes that of the heroes in Homer. The all-round enthusiasm for inflicting death and injury as a way of life, and a basis of status, may of course lead us to regard these as more action heroes than moral heroes. In the Homeric context, and discussions of other pre-urban societies dominated by a warrior aristocracy, the word ‘hero’ often has a descriptive political and social aspect, which is more relevant than any sense of moral approbation in the term hero.

The classic discussions of warrior ‘hero’ societies since Homer and Tacitus are Giambattista Vico’s New Science (1744) and Friedrich Nietzsche’s On the Genealogy of Morality (1887), and these should be seen in the context of Enlightenment writing on ‘savage’ and ‘barbarian’ stages of history. Nietzsche’s contribution comes from the time in which anthropology is beginning to emerge as a distinct academic discipline, tending at that time anyway to concentrate on ‘primitive’ peoples.

The Sagas give a literary impression of a society in which the state has not developed as an institution, which could be regarded as evidence of ‘primitiveness’. However, the Icelanders had originally left the monarchical state of Norway, which features heavily in the Sagas, and they were in touch with the monarchical state of England, in a sense which could include Viking raids, as well as warrior service to Anglo-Saxon kings. So it would not be correct to say that the Icelanders were at some early, simple stage where they did not know anything different, as they had chosen to reject monarchical institutions, or at least had never found it worth the trouble to go about creating a monarchy with a palace, an army, great lords, taxes, and law courts appointed from above.

What the Icelander had was a dispersed set of rural communities, in which there were no towns. The centre of the ‘nation’ was not a capital city, but an assembly known as ‘althing’, which combined representative, law making, and judicial functions, with the judicial function predominating. There was not much in the way of political decision-making since there was no state, and the laws were those that existed by custom, not through deliberate law-making.

The judicial function was exercised through judgements, which were essentially mediations on disputes that could also be brought before lower level assemblies-courts. The right to participate in the assembly with a vote was restricted to a class of local notables, though not a hereditary aristocratic class.

Judging by the Sagas, the judgments of the Althing may have been influenced by the numbers present on either side, particularly if they were armed. Only one person was employed by the Althing, a ‘law speaker’, whose compensation was taken from a marriage fee. At least in the earlier years of the Icelandic community, from 870 to 1000, there seems to have been nothing else in the way of a state. Conversion to Christianity in about 1000 led to tithes (church taxes) and a good deal more institutional interest in what religion Icelanders might be practising. In the thirteenth century the tendency towards more, if still very little, state was completed by incorporation into the domains of the King of Norway.

The Sagas do not give a complete institutional description, but are a large part of the evidence for what is known about pre-Christian Iceland. The stories of warrior-heroes and families often takes us into the judicial life of the community, as violent disputes arise. There is no police force of any kind, so disputes initially dealt with by force, including killing.

Sagas which concentrate on warrior heroes suggest that considerable property and local influence could be built up through individual combats in which the winner kept the property of the loser, that is the person who died in the combat. The more family based sagas suggest that at least some of the time, combat might lead to the loser ceding some land rather than having to fight to the death.

Presumably, in some cases, the warrior honour culture led to anyone challenged to combat being forced by custom to agree to do so, which gave particularly effective warriors a chance to become major land owners through willingness to issue challenges. The warrior-oriented sagas really suggest a society in which some part of the population were constantly using deadly violence to protect and advance their status, or simply in reaction to minor slights on honour, and the use of such violence could lead to the killing of a defenceless child.

The use of murderous violence against those unwilling, or unable, to fight back was deterred and punished to some degree by a system of justice which was in large part voluntary. There was no compulsion to attend the Althing, or lower assemblies, and no means to enforce attendance except the violence of those wishing to make a legal complaint, should they wish the accused to be present. The punishments, even for the most extreme violence, were never those of physical punishment, prison, or execution.

Judgments required economic compensation, or at the most extreme outlawed the guilty party, who appears to have been largely given the time and opportunity to leave Iceland unmolested before the most severe consequences out outlaw status could be applied. Outlawing of course removes legal protection from the person punished who can therefore be murdered, or s subject to some other harm, without a right to legal complaint. Outlawing often seems to have been the result of non-payment of compensation demanded by the court.

The judicial system was essentially voluntary, and judging from the sagas a lot of disputes were settled by private violence, which could include murder of supposed witches and torture of prisoners. Victims of violence, or other harms, were only protected by law as far as they or their friends, neighbours, or families, were willing and able to go to court, demand an official judgement authorising punishment, and enforce it.

Slavery was normal, but there was some legal protection of slaves, in so far as anyone in their community was interested in ensuring enforcement. Jealousy and competition between neighbouring families may have helped produce legal protectors for the socially weak, but this is maybe not the most reassuring form of protection.

For liberty community fans of the example of Iceland from 870-1000, it is a example of how anarchism can work; that is, it is an example of how there can be law and a judicial system without a state beyond judicial assemblies and the one employee of the most important assembly.

Medieval Iceland was a functioning society, which was perhaps not as sophisticated as England, France, the German Empire (Holy Roman Empire), the Byzantine Empire (which appears in the Sagas as the Greek Empire), or caliphate of Cordoba, just to name the most powerful European states of the time, but did leave a significant literary legacy in the Sagas, as even the most violent warrior-heroes wrote poetry some times. It was a rural seagoing trading community, in which violence was no more prevalent than other parts of Medieval Europe, and a tolerable existence was maintained in the face of a very harsh nature.

The arguments for a less enthused attitude toward Iceland as a liberty-loving model include the very simple nature of the society with no towns, the existence of slavery, and the lack of comprehensive enforcement of law. In general there is the oddity of taking as model of anything a situation in which there was no protection from violence, and no other harms, unless someone or some group with some capacity to exert force, brought a case to the attention of the court and was able to enforce any decision.

Medieval Iceland was a society in which violence was not always punished and where those inclined to use violence for self-enrichment could live without consequences, either through ignoring laws, or making use of laws and customs, which created opportunities to take property on an issue of ‘honour’. The courts and laws of Medieval Iceland were maybe adequate for creating some restraint on a community containing a significant proportion of Viking raiders regarding murderous violence on a systematic scale as legitimate and even as an honourable way to increase wealth.

On the whole I lean more in the second direction, I certainly see no reason to see near-anarchist Iceland as better for liberty in its time than the self-governing merchant towns of the Baltic, the Low Countries, and northern Italy. There is no evidence that Medieval Europeans were ever inspired to take Iceland as a great example of anything. The intermittently contained violence of slave owning landholders is not a great justification for the semi voluntary legal system, and near non-state.

Having said that, the emphasis on justice as mediation, and on punishments limited to exile and compensatory payments, does have something to say to those who prefer to limit the power of the state over individuals, who wish to prevent the punishment of crime become the reason for an incarcerating state, trying to extend that model of power into every aspect of social life.

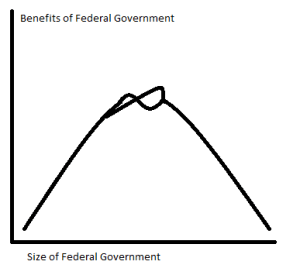

The system of law without state compulsion did not succeed in sustaining itself beyond a few centuries, but that is enough to suggest that there are some possibilities of viable modern national communities existing with less of a centralised state and coercive judicial-penal-police apparatus than is now normal. The limitations of Saga Icelandic liberty apply to the antique slaveholding republics, and in some part to European states and the USA when some forms of liberty were increasing while plantation slavery was expanding. The Icelandic Medieval example is at the very least worth contemplation with regard to the possibilities of limiting the coercive state.

Note on texts. As with other classics, many editions are available and I usually leave readers of these posts to find one in the way that is most convenient for them. In this case though, I would like to point out the following extensive and scholarly edition, which includes some useful historical background as well as literary discussion.

The Sagas of the Icelanders: A Selection, Viking [hah Viking!]-Penguin, New York NY, 2000.