I sometimes part ways with many of my libertarian and classical liberal friends in that I do have some amount of tentative concern for income/wealth inequality (for the purposes of this article, the otherwise important economic distinction between the two is not particularly relevant since the two are strongly correlated with each other). Many libertarians argue that inequality ultimately doesn’t matter. There is good reason to think this drawing from the classic arguments of Nozick and Hayek about how free exchange in a market economy can often interrupt preferred distributions.

The argument goes like this: take whatever your preferred distribution of income is, be it purely egalitarian or some sort of Rawlsian distribution such that the distribution benefits only the worst off in society. Assume there is one individual in the economy who has some product or service everyone wants to buy (in Nozick’s example it was Wilt Chamberlain playing basketball), and let everyone pay a relatively small amount of income to that one individual. For example, assume you have a society with 10,000 people all who start off with an equal endowment of $5 and all of them decide to pay Wilt Chamberlain $1 to watch him play basketball. Very few people would object to those individual exchanges, yet at the end Wilt Chamberlain ends up with $10,005 dollars and everyone else has $4, and our preferred distribution of income has been grossly upset even though the individual actions that led to that distribution are not objectionable. In other words, allowing for free exchange precludes trying to construct an optimal result of that free exchange (a basic consequence of recognizing spontaneous order).

Further, these libertarians argue, it is more important to ensure that the poor are better off in absolute terms than to ensure they are better off relative to their wealthier peers. Therefore, if a given policy will increase the wealth of the wealthiest by 10% and the poorest by 5%, there is no reason to oppose this policy on the grounds that it increases inequality because the poor are still made richer. Therefore, it is claimed, we should focus on policies that improve economic growth and the incomes of the poor and be indifferent as to its impact on relative inequality, since those policies are strongly correlated with bettering the economic conditions of the poor. In fact, as Mises Argued in Liberalism and the Classical Tradition, a certain amount of inequality is necessary for markets to function: they create a market for luxury goods that can be experimented and developed into future mass-consumption goods everyone can consume. Not everyone could afford, for an example, an IPod when it first came out, however today MP3 players are cheap and plentiful because the very wealthy were able to demand it when it was very expensive.

I agree with my libertarians in thinking that this argument is largely correct, however I do not think it proves, as Hayek argued, that social justice (understood in this context as distributive justice) is a “mirage” or that we should be altogether unconcerned with wealth or income distributions. All this argument does is mean that there is no overall deontological theory for an ideal income distribution, but there still might be good consequentialist reasons to think that excessively unequal distributions can impact many of the things that classical liberals tell us to worry about, such as the earnings of the poor, more free political economic outcomes, or overall economic growth. Further, even on Nozick’s entitlement theory of justice, we might oppose income inequality if it arises through unjust means. Here are five reasons why libertarians and classical liberals should be concerned about income inequality (note that they are mostly empirical reasons, not claims about the nature of justice):

1) Income Inequality as a Result of Rent Seeking

Certain government policies result in uneven income distribution. For an example, a paper by Patrick MacLaughlin and Lauren Stanley at the Mercatus Center empirically analyze the regressive effects of regulatory policy. Specifically, Stanley and MacLaughlin find that high barriers to entry create barriers to entry which worsens income mobility. Poorer would-be entrepreneurs cannot enter the market if they must, for an example, pay thousands of dollars for a license, or spend a large amount of time getting costly education and certifications to please some regulatory bureaucracy. This was admitted even by the Obama Administration in a recent report advising reform of occupational licensing laws. As basic public choice theory teaches, regulators are subject to regulatory capture, in which established business interests lobby regulators to erect barriers to entry to harm would-be competitors. Insofar as inequality is a result of such rent-seeking, libertarians have an obvious reason to oppose it.

Many other policies can worsen inequality. When wealthy corporations receive artificial monopolies from policies such as excessive intellectual property laws, insulating them from competition or when they gain wealth at the expense of poorer taxpayers through improper subsidies. When the government uses violent policing tactics to unequally enforce drug laws against poorer communities, or when it uses civil asset forfeiture to take the property of the worst off. When the government uses eminent domain to take the property of disadvantaged individuals and communities in the name of public works projects, or when they implement minimum wage laws that displace low-skilled workers. Or, if the structure of welfare benefits discourages income mobility, which also worsens inequality. There are a myriad of bad government policies which benefit the rich and exploit the poor, some of which are a direct result of rent-seeking on behalf of the wealthy.

If the rich are getting richer, or if the poor are stopped from becoming wealthier, as a result of government coercion, even Nozick’s entitlement theory of justice calls for us to be skeptical of the resulting income distribution. As Matt Zwolinski argues, income distributions are not only a result of, pace Nozick, a result of the free exchanges of individuals, but they are also a result of the institutions in which those individuals exchange. Insofar as inequality is a result of unjust institutions, we have good reason to call that inequality unjust.

Of course, that principle is still very hard to empirically apply. It is hard to tell how much of an unequal distribution is a function of bad institutions and how much is a function of free exchange. However, this means we can provide very limited theories of distributive justice not as constructivist attempts to mold market outcomes to our moral desires, but as rough rules of thumb. If it is true that unequal distributions are a function of bad institutions, then unequal distributions should cause us to re-evaluate those institutions.

2) Income Inequality and Government Exploitation

Of course, many with more Marxist inclinations will argue that any amount of economic inequality will inherently result in class-based exploitation. There are very good, stand-by classical liberal (and neoclassical economic) reasons to reject this as Marxian class analysis as it depends on a highly flawed labor theory of value. However, that does not mean there is not some correlation between some notion of macro-level exploitation of the worst-off and high levels of inequality which libertarians have good reason to be concerned about, for reasons closely related to rent-seeking. Those with a high amount of economic power, particularly in western democracies, are very likely to also have a strong influence over the policies set by the government. There is reason to fear that this will create a class of wealthy people who, through political rent-seeking channels discuss earlier, will control state policies and institutions to protect their interests and wealth at the expense of the worst-off in society. Using state coercion to protect oneself at the expense of others is, under any understanding of the term, coercion. In this way, income inequality can beget rent-seeking and regressive policies which lead to more income inequality which leads to more rent-seeking, leading to a vicious political-economic cycle of exploitation and increasing inequality. In fact, even early radical classical liberal economists applied theories of class analysis to this type of problem.

3) Inequality’s Impacts on Economic Growth

There is a robust amount of empirical literature suggesting that excessive income inequality can harm economic growth. How? The Economist explains:

Inequality could impair growth if those with low incomes suffer poor health and low productivity as a result, or if, as evidence suggests, the poor struggle to finance investments in education. Inequality could also threaten public confidence in growth-boosting policies like free trade, says Dani Rodrik of the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.

Of course, this is of special concern to consequentialist classical liberals who claim we should worry mostly about the betterment of the poor in absolute terms, since economic growth is strongly correlated with bettering living standards. There is even some reason for these classical liberals, given their stated normative reasons, to (at least in the short-term given that we have unjust institutions) support some limited redistributive policies, but only those that are implemented well and don’t worsen inequality or growth (such as a Negative Income Tax), insofar as it boosts growth and helps limited the growth of rent-seeking culture described with reasons one and two.

4) Inequality and Political Stability

There is further some evidence that income inequality increases political instability. If the poor perceive that current distributions are unjust (however wrong they may or may not be), they might have social discontent. In moderate scenarios, (as the Alsenia paper I linked to argue) this can lead to reduced investment, which aggravates third problem discussed earlier. In some scenarios, this can lead to support for populist demagogues (such as Trump or Bernie Sanders) who will implement bad policies that not only might harm the poor but also limit individual liberty in other important ways. In the most extreme scenarios (however unlikely, but still plausible), it can lead to all-out violent revolutions and warfare. At any rate, libertarians and classical liberals concerned with ensuring tranquility and freedom should be concerned if inequality increases.

5) Inequality and Social Mobility

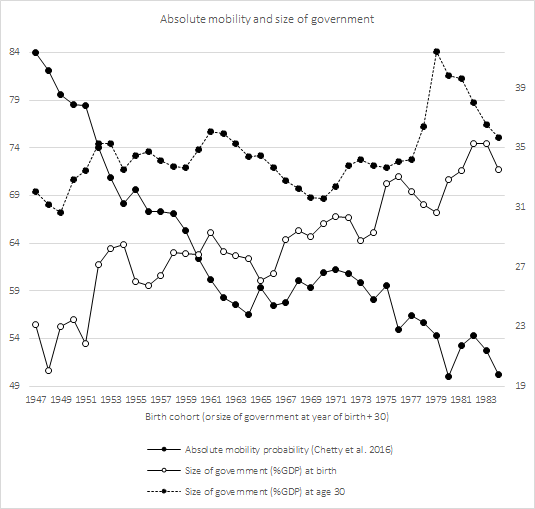

More meritocratic-leaning libertarians might say we should be concerned about equal opportunities rather than equal outcomes. There is some evidence that the two are greatly linked. In particular, the so-called “Great Gatsby Curve,” which shows a negative relationship between economic mobility and income inequality. In other words, unequal outcomes can undermine unequal opportunities. This can be because higher inequality means unequal access to certain services, eg. Education, that can enable social mobility, or that the poorer may have fewer connections to better-paying opportunities because of their socio-economic status. Of course, there is likely some reverse causality here; institutions that limit social mobility (such as those discussed in problem one and two) can be said to worsen income mobility intergenerationally, leading to higher inequality in the future. Though teasing out the direction of causality empirically can be challenging, there is reason for concern here if one is concerned about social mobility.

The main point I’m getting at is nothing new: one need not be a radical leftist social egalitarian who thinks equal economic outcomes are necessarily the only moral outcomes to be concerned on some level with inequality. How one responds to inequality is empirically dependent on the causes of the problems, and we have some good reasons to think that more limited government is a good solution to unequal outcomes.

This is not to say inequality poses no problem for libertarians’ ideal political order: if it is the case that markets inherently beget problematic levels of inequality, as for example Thomas Piketty claims, then we might need to re-evaluate how we integrate markets. However, there is good reason to be skeptical of such claims (Thomas Piketty’s in particular are suspect). Even if we grant that markets by themselves do lead to levels of inequality that cause problems 3-5, we must not commit the Nirvana fallacy. We need to compare government’s aptitude at managing income distribution, which for well-worn public choice reasons outlined in problems one and two as well as a mammoth epistemic problem inherent in figuring out how much inequality is likely to lead to those problems, and compare it to the extent to which markets do generate those problems. It is possible (very likely, even) that even if markets are not perfect in the sense of ensuring distribution that does not have problematic political economic outcomes, the state attempting to correct these outcomes would only make things worse.

But that is a complex empirical research project which obviously can’t be solved in this short blog post, suffice it to say now that though libertarians are right to be skeptical of overarching moralistic outrage about rising levels of inequality, there are other very good empirical reasons to be concerned.