Trump has now taken extralegal military action in Venezuela. Trump is strongly considering such action in Iran. And Trump keeps flirting with aggressive globally destabilizing military annexation of Greenland, a NATO ally. Many people are acting perplexed. After all, didn’t libertarian “genius” and totally-not-delusional-reactionary Walter Block tell us back in 2016 that libertarians should vote for Trump because he is anti-war? After this proved to be false the first term, didn’t totally-not-delusional-reactionary Walter Block then tell us again case for libertarianism was that he was anti-war and anti-foreign intervention, and that he was super cereal this time?

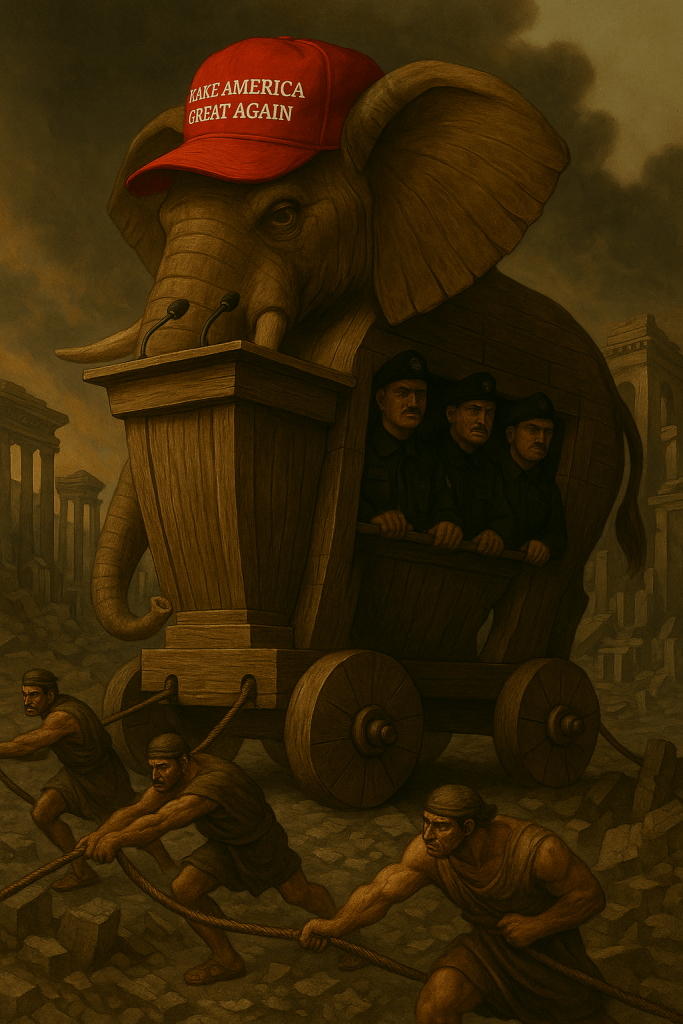

Sarcasm aside, I think it is worth revisiting why Trump’s foreign policy turn towards a radical sort of imperialist interventionism is so evil and unsurprising. I was confident back in 2016 that he was always going to be an old-school imperialist who uses US military conquest purely for resource extraction in a way that would be far worse than neocon warmongering. I wrote at the time, following Zach Beauchamp (who continues to emphasize this point), that Trump’s foreign policy was neither the neo-conservative interventionism of the Clintons and Bushes of the world, nor the principled anti-interventionism of libertarian scholars like Christopher Coyne and Abigail Hall, nor even the nationalist isolationism of paleoconservatives like James Buchanan. Instead, Trump’s foreign policy has always (quite consistently, since he was still a pro-choice democrat in the 90s) been about advancing inchoate national economic and political interests—which really just means the interests of the politically connected.

This connection between Trump’s completely crankish economic nationalism and his imperialist foreign policy is even tighter now than it was then. It seems Trump is likely facing a rejection of his unconstitutional overreach of unilaterally applying economically suicidal tariffs from SCOTUS. The tariffs, which originally, might I add, were based on perhaps the single dumbest attempt to do economics I have ever seen, appeared to be lifted straight from ChatGPT, given that his main economic advisor on these matters, Peter Navarro, is literally a fraudster. As a result, he now seems to be manufacturing a national security crisis so he can impose tariffs without congress’ blessing.

But I do not want to revisit Trump’s imperialist foreign policy just to gloat. I also want to revisit and restate why this foreign policy is unbelievably unjust and self-destructive. What I wrote back in 2016 is still worth reposting at length:

First, Trump’s style of Jacksonian foreign policy is largely responsible for most of the humanitarian atrocities committed by the American government. Second, Trump’s economic foreign policy is antithetical to the entire spirit of the liberal tradition; it undermines the dignity and freedom of the individual and instead treats the highest good as for the all-powerful nation-state (meaning mostly the politicians and their special interests) as the end of foreign policy, rather than peace and liberty. Finally, Trump’s foreign policy fails for the same reasons that socialism fails. If the goals of foreign policy are to represent “national interest,” then the policymaker must know what that “national interest” even is and we have little reason to think that is the case, akin to the knowledge problem in economic coordination.

… This is because the Jacksonian view dictates that we should use full force in war to advance our interests and the reasons for waging war are for selfish rather than humanitarian purposes. We have good reason to think human rights under Trump will be abused to an alarming degree, as his comments that we should “bomb the hell out of” Syria, kill the noncombatant families of suspected terrorists, and torture detainees indicate. Trump is literally calling for the US to commit inhumane war crimes in the campaign, it is daunting to think just how dark his foreign policy could get in practice.

To reiterate: Trump’s foreign policy views are just a particularly nasty version of imperialism and colonialism. Mises dedicated two entire sections of his chapter on foreign policy in Liberalism: The Classical Tradition to critiquing colonialism and revealing just how contrary these views are to liberalism’s commitment to peace and liberty. In direct opposition to Trump’s assertions that we should go to war to gain another country’s wealth and resources and that we should expand military spending greatly, Mises argues:

“Wealth cannot be won by the annexation of new provinces since the “revenue” deprived from a territory must be used to defray the necessary costs of its administration. For a liberal state, which entertains no aggressive plans, a strengthening of its military power is unimportant.”

Mises’ comments on the colonial policy in his time are extremely pertinent considering Trump’s calls to wage ruthlessly violent wars and commit humanitarian crises. “No chapter of history is steeped further in blood than the history of colonialism,” Mises argued. “Blood was shed uselessly and senselessly. Flourishing lands were laid waste; whole peoples destroyed and exterminated. All this can in no way be extenuated or justified.”

Trump says the ends of foreign policy are to aggressively promote “our” national interests, Mises says “[t]he goal of the domestic policy of liberalism is the same as that of its foreign policy: peace.” Trump views the world as nations competing in a zero-sum game and there must be one winner that can only be brought about through military conquest and economic protectionism, Mises says liberalism “aims at the peaceful cooperation between nations as within each nation” and specifically attacks “chauvinistic nationalists” who “maintain that irreconcilable conflicts of interest exist among the various nations[.]” Trump is rabidly opposed to free trade and is horrifically xenophobic on immigration, the cornerstone of Mises’ foreign policy is free movement of capital and labor over borders. There is no “congruence” between Trump and any classically liberal view on foreign policy matters in any sense; to argue otherwise is to argue from a position of ignorance, delusion, or to abandon the very spirit of classical liberalism in the first place.

…Additionally, even if we take Trump’s nationalist ends as given, the policy means Trump prefers of violent military intervention likely will not be successful for similar reasons to why socialism fails. Christopher Coyne has argued convincingly that many foreign interventions in general fail for very similar reasons to why attempts at economic intervention fail, complications pertaining to the Hayekian knowledge problem. How can a government ill-equipped to solve the economic problems of domestic policy design and control the political institutions and culture of nations abroad? Coyne mainly has the interventionism of neoconservatives and liberals in mind, but many of his insights apply just as well to Trump’s Jacksonian vision for foreign policy.

The knowledge problem also applies on another level to Trump’s brand of interventionism. Trump assumes that he, in all his wisdom as president, can know what the “national interest” of the American people actually is, just like socialist central planners assume they know the underlying value scales or utility functions of consumers in society. We have little reason to assume this is the case.

Let’s take a more concrete example: Trump seems to think one example of intervention in the name of national interest is to take the resource of another country that our country needs, most commonly oil. However, how is he supposed to know which resources need to be pillaged for the national interest? There’s a fundamental calculation problem here. A government acting without a profit signal cannot know the answer to such a problem and lacks the incentive to properly answer it in the first place as the consequences failure falls upon the taxpayers, not the policy makers. Even if Trump and his advisors could figure out that the US needs a resource, like oil, and successfully loots it from another country, like Libya, there is always the possibility that this artificial influx of resources, this crony capitalist welfare for one resource at the expense of others, is crowding out potentially more efficient substitutes.

For an example, if the government through foreign policy expands the supply of oil, this may stifle entrepreneurial innovations for potentially more efficient resources in certain applications, such as natural gas, solar, wind, or nuclear in energy, for the same reasons artificially subsidizing these industries domestically stifle innovation. They artificially reduce the relative scarcity of the favored resource, reducing the incentive for entrepreneurs to find innovative means of using other resources or more efficient production methods. At the very least, Trump and his advisors would have little clue how to judge the opportunity cost of pillaging various resources and so would not know how much oil to steal from Libya. Even ignoring all those problems, it’s very probable that it would be cheaper and morally superior to simply peaceably trade with another country for oil (or any other resource) rather than waging a costly, violent, inhumane war in the first place.

Having said all that, there is plenty I got wrong in picturing Trump as an old-school imperialist. During Trump’s first term, I underestimated the extent to which institutional constraints would stop him from acting on his worst nationalist and imperialist impulses. But this term, those constraints are gone. The Mattises, Tillersons, Boltons, and Pences of the world have been replaced with the Vances, Noems, Rubios, and Hegseths. As a result, thinking of Trump as an old-school imperialist and nationalist is becoming more accurate since he is allowed to act on his irrational, deranged impulses.

Second, I failed to distinguish sufficiently between resource extraction through indirect means of violent regime change, tariffs, weapons supply, and 19th-century colonialist-style direct annexation versions of it. I do still think that if Trump really did what he most consistently wants he would do quite a bit of annexation and old school colonialism (see his comments on Greenland and Canada), but he seems a bit more content than I projected back then to use military force to install stooges and puppet regimes for resource extraction (as he has sought to do in both Gaza and now Venezuela). Which, to your point, is not as different from the Nixon/Bush/Clinton/Reagan type intervention as reactionary centrists would have you believe, but the nakedness of the extractive nationalist motivation does mark a difference that encourages even more brazenly cruel, more illegal, and more strategically incoherent and unpredictable interventionist warmongering.

Thirdly, and most obviously, I greatly overestimated his coherence on foreign policy. Whether it is him handicapping US influence in the Pacific by withdrawing from the TPP while implementing tariffs on Chinese goods to seem tough in the first term, which just gave China more leverage in the region. Or whether it’s his delusional flip-flopping on Russia and Ukraine based on who he talked to last, constantly this term. Or whether it’shis random provocation against Iran in 2019 by killing one of their generals. Or whether it’s his insane flip-flopping between Nuclear War talk and sychophancy with North Korea. Or the total randomness of his attacking Venezuela for more domestic than foreign policy reasons now. He is simply far more impulsive and deranged than I would have predicted in 2016. This part of that old article seems especially stale now:

After all, it doesn’t matter so much the character of public officials as the institutional incentives they face. But in matters of foreign policy problems of temperament and character do matter because the social situation between foreign leaders in diplomacy can often make a huge difference.

I did hedge that by allowing that Trump may be a uniquely unfit person so as to constitute a sui-generis case. But I should have been more emphatic about that: Trump really is a uniquely world-historically dangerous monster, and he has gotten more and more incoherent and impulsive over the years with his cognitive decline.

Finally, the biggest miss in my analysis of Trump’s foreign policy back then is that I put far too much emphasis on Trump’s focus on material goods, thinking he really just thought of geopolitics like a 12-year-old approaches a turn-based strategy game like Risk in just accruing more stuff. But in reality, his approach is far more disturbing and vile than even that. It is not simply about getting oil for US oil companies. In the case of Venezuela, oil execs do not seem so gun-ho. As one private equity investor told the Financial Times last week, “No one wants to go in there when a random fucking tweet can change the entire foreign policy of the country.” Indeed, the political risk is so big there Exonn’s CEO has called Venezuela “uninvestable” and Trump is trying to force oil companies to misallocate capital to Venezuela.

Narrow left-wing materialists’ critiques like mine misfire because they treat material resources as the main thing. It is not the oil per se that Trump wants, but what the oil represents. He is instead approaching international geo-politics like an 8-year-old driven by malignant narcissism: he wants symbols of nationalist masculine domination. Indeed, when asked why he wanted Greenland, Trump was quoted as saying:

Because that’s what I feel is psychologically needed for success. I think that ownership gives you a thing that you can’t do, whether you’re talking about a lease or a treaty. Ownership gives you things and elements that you can’t get from just signing a document.

Indeed, the fact that Greenland looks big on a Mercator projection of the earth has as much to do with why Trump wants it as the oil. As Trump continues his authoritarian assaults on individual liberty domestically and pursues semiotic nationalist domination internationally, one can only vainly pray that something keeps his dark, demonic, twisted sadist fantasies in check without devolving into a true civilization-level threat.