What is the long-term legacy of political persecutions? Here I want to present the main findings of my recent research with Melanie Meng Xue (UCLA Anderson). Our research is an attempt to undercover how a legacy of political persecution can shape social capital and civil society by studying imperial China. The full version of the paper is available here.

We know from other research that particular institutions, policies, and events can have a detrimental and long-lasting impact on economic and political outcomes (e.g. Nunn 2011, Voigtländer and Voth, 2012). But it is hard to find a setting where we can study the long-run impact of autocratic institutions. A key feature of autocracy is the use of persecutions to intimidate potential opponents. In our paper, Melanie and I argue that the intensification of imperial autocracy that took place in the High Qing period (1680-1794) provides an ideal setting to study the impact of such persecutions.

Qing China

The High Qing period was one of great political stability, imperial expansion, and internal peace. Economic historians like Bin Wong and Ken Pomeranz have shown that China possessed a flourishing market economy during this period; it experienced Smithian economic growth and a massive demographic expansion. Rulers such as the Kangxi (1661-1722) and Qianlong Emperors (1735-1794) are seen as among the most successful in Chinese history. Nevertheless, as ethnic Manchus, these rulers were extremely sensitive to possible opposition from the Han Chinese. And during this period Qing tightened control over the gentry and implemented a policy of the systematic persecution of dissent. (Figure 1 depicts the Manchu conquest of China.)

The Literary Inquisitions

The focus of our paper is on the impact of persecutions conducted by Qing China against individuals suspected of expressing disloyalty. We study the impact of these state-orchestrated persecutions on the social fabric of society. This allows us to speak to the kinds of concerns that authors like Hannah Arendt and George Orwell expressed about the long-run impact of totalitarianism in the 20th century.

These persecutions are referred to by historians as ‘literary inquisitions’. Existing scholarship suggests that the resulting fear of persecution elevated the risks facing writers and scholars, and created an atmosphere of oppression and a culture of distrust which deterred intellectuals from playing an active role in society. But these claims have never been systematically investigated. Putting together several unique datasets for historical and modern China, we explore the impact of literary inquisitions on social capital in Qing China and trace its long-run impact on modern China through its effect on cultural values.

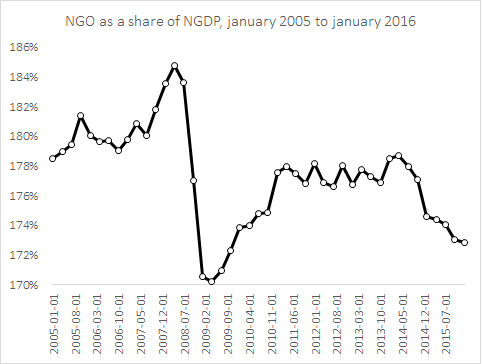

To conduct our analysis, we use data on 88 inquisition cases. We match the victims of each case (there are often multiple victims per case) to their home prefecture. This data is depicted in Figure 1. Since prefectures varied greatly in their economic, social, and political characteristics we conduct our analysis on a matched sample. This ensures that the prefectures “treated” by a literary inquisition are similar in terms of their observables to those we code as “untreated”. As our data is a panel, we are able to exploit variation across time as well as variation in space.

While individuals could be persecuted for a host of reasons, these were all but impossible to anticipate ex ante. Cases were referred to the emperor himself. Frederic Wakeman called this “the institutionalization of Imperial subjectivity.” The standard punishment in such cases was death by Lingchi or (slow slicing) and the enslavement of all one’s immediate relatives. In some cases, however, the guilty party would be executed by beheading. These persecutions aimed to deter opposition to Qing rule by signaling the ability of the Emperor to hunt down all potential critics or opponents of the regime.

The Impact of Literary Inquisitions on Social Capital

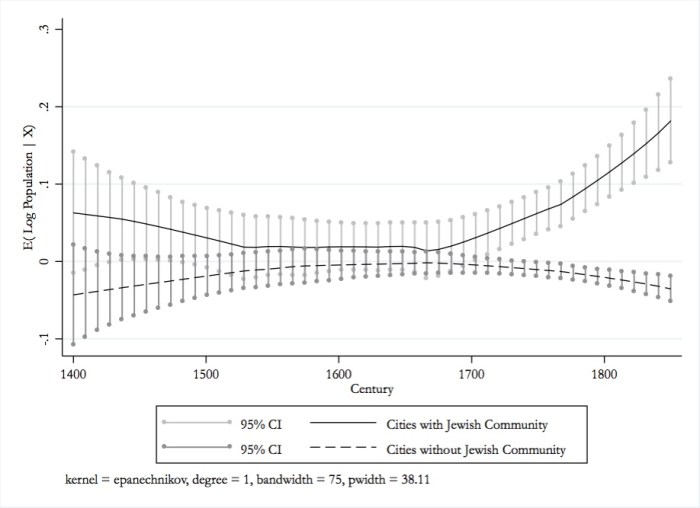

We initially focus on the impact of persecution on the short and medium-run using our historical panel. We first examine the effects on the number of notable scholars. In our preferred specification we find that a literary inquisition reduced the number of notable scholars in a prefecture by 33 percent relative to the sample mean.

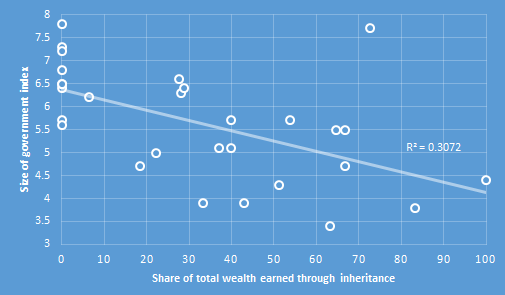

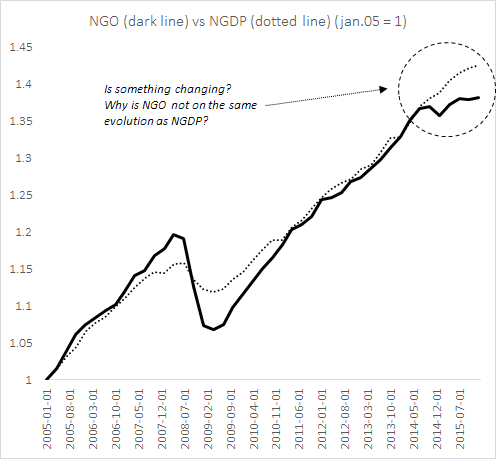

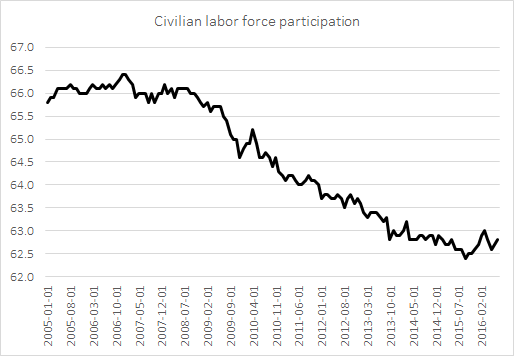

We go on to show the effect of persecutions on collective participation among the gentry in China. Our measure of collective participation in civil society is the number of charitable organizations. Charitable organizations played an important role in premodern China providing disaster relief and local public goods such as repairing local roads. They were non-governmental organizations and played an important role alongside the government provision of disaster relief. In our preferred empirical specification, we find that a persecution number of charitable organizations by 38 percent relative to the sample mean.

These results are in keeping with the argument that literary inquisition had a major psychological impact on Chinese society. They are consistent with the rise of “inoffensive” literary subjects during the Qing period that have documented by historians. To reduce the risk of persecution, intellectuals scrupulously avoided activities that could be interpreted as constituting an undermining of Qing rule. Instead they “immersed themselves in the non-subversive “sound learning” and engaged in textual criticism, bibliography, epigraphy, and other innocuous, purely scholarly pursuits” (Wiens, 1969, 16).

The Impact of Literary Inquisitions on 20th Century Outcomes

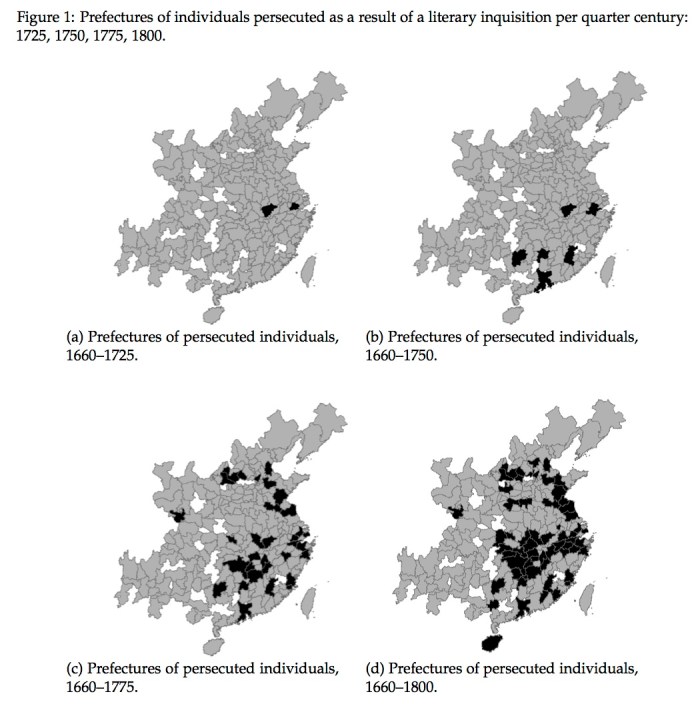

We go on to examine how the effects of these persecutions can be traced into the 20th century. In particular, we focus on the provision of basic education at the end of Qing dynasty. In late 19th and early 20th century China, there was no centralized governmental provision of primary schools. Basic education remained the responsibility of the local gentry who ran local schools.

Thus the provision of education at a local level was dependent on the ability of educated individuals to coordinate in the mobilization of resources; this required both cooperation and trust. We therefore hypothesize that if the persecution of intellectuals had a detrimental impact on social capital, it should also have negatively affected the provision of basic education.

We find that among individuals aged over 70 in the 1982 census – hence individuals who were born in the late Qing period – a legacy of a literary inquisition is associated with lower levels of literacy. This reflects the impact of literary inquisition on the voluntary schools provided by the gentry and is not associated with lower enrollment at middle school or high school. We show that result is robust to controlling for selective migration and for the number of death caused by the Cultural Revolution.

Finally, we show that literary inquisitions generated a cultural of political non-participation. Drawing on two datasets of political attitudes – the Chinese General Social Survey (CGSS) and the Chinese Political Compass (CPoC) – we show that individuals in areas in which individuals were targeted during literary inquisitions are both less trusting of government and less interested in political participation.

Finally, we find that individuals in prefectures with a legacy of literary inquisitions are less likely to agree that: “Western-style multi-party systems are not suitable for China” (Q 43.). This suggests that in areas affected by literary inquisitions individuals are also more skeptical of the claims of the Chinese government and more open to considering alternative political systems. Similarly, individuals in affected prefectures are more likely to disagree with the statement that: “Modern China needs to be guided by wisdom of Confucius/Confucian thinking.”

In summary, our analysis suggests that autocratic rule reduced social capital and helped to produce a culture of political quietism in pre-modern China. This has left a legacy that persisted into the 20th century. These findings have implications for China’s current political trajectory. Some scholars anticipate China undergoing a democratic transition as it’s economy develops (Acemoglu and Robinson, 2012). Others point to China as an example of “authoritarian resilience.” By showing that a long-history of autocratic rule and political persecutions can produce a culture of political apathy, our results shed light on a further and previously under-explored source of authoritarian resilience.