- Charles de Gaulle’s alternative model for Europe Samuel Gregg, Law & Liberty

- Distance from Khe Sanh to Kandahar: 0 Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Fear of the Ivory Tower Jonathon Catlin, JHIBlog

- Anarchy and public goods Pierre Lemieux, EconLog

Confessions of a Fragilista: Talebian Redundancies and Insurance

I’ve been on a Taleb streak this year (here, here and here). Nassim Nicholas Taleb, that is, the options trader-turned-mathematician-turned public intellectual (and I even managed to get myself on his infamous blocklist after arguing back at him). Many years ago, I read Fooled by Randomness but for some reason it didn’t resonate with me and I wasn’t seeing the brilliance.

Last spring, upon reading former poker champion Annie Duke’s Thinking in Bets and physicist Leonard Mlodinow’s The Drunkard’s Walk, I plunged into Taleb land again, voraciously consuming Fooled, The Black Swan and Skin in the Game, followed by Antifragile just a few months ago.

Taleb is a strange creature; vastly productive and incredibly successful, everything he touches does not quite become gold, but surely stirs up controversy. What he’s managed to do in his popular writing (collected in the Incerto series) is to tie almost every aspect of human life into his One Big Idea (think Isaiah Berlin’s hedgehog): the role of randomness, risk and uncertainty in everyday life.

One theme that comes up again and again is the idea of redundancies: having several different and overlapping systems – back-ups to back-ups – that minimize the chance of fatally bad outcomes. The failures of one of those systems will not result in the extremely bad event you’re trying to avoid.

Focusing primarily on survivability – “absorbing barriers” – through the handed-down wisdom of the Ancients and the Classic, the take-away lesson for Taleb in almost all areas of life is overlapping redundancies. Reality is complicated, and the distribution from which events are drawn is not a well-behaved Gaussian normal distribution, but one of thick tails. How thick nobody knows, but wisdom in the presence of absorbing barriers suggest that taking extreme caution is a prudent long-term strategy.

Of course, in the short run, redundancy amounts to “wasted” resources. In chapter 4 of Fooled, Taleb relates a story from his option trading days where a client angrily calling him up about tail-risk insurance he had sold them. The catastrophic event from which the insurance protected had not taken place, and so the client felt cheated. This behavior, Taleb maintains quite correctly, is idiotic. After all, if an insurance company’s clients consist of only soon-to-be claimants, the company won’t exist for long (or it prices insurance at prohibitively high rates, undermining the business model).

Same thing applies for one of his verbose rants about airline “efficiency,” a rather absurd episode of illustrating “asymmetry” – the idea that downside risks are larger than upside gains. Consider a plane departing JFK for London, a trip scheduled to take 7h trip. Some things can happen to make the trip quicker (speedy departure, weather conditions, landing slot available etc), but only marginally; it would, for instance, not be possible to arrive in London after only an hour. In contrast, the asymmetry arises as there are many things that can delay the trip from mere minutes to infinity – again, weather events, mechanical failures, tech or communication problems.

So, when airlines striving to make their services more efficient by minimizing turnaround time – Southwest’s legendary claim to fame – they hit Taleb’s antifragile asymmetry; getting rid of redundant time on the ground, makes the process of on-loading and off-loading passengers fragile. Any little mistake can cause serious delays, delays that accumulate and domino their way through crowded airport networks.

Embracing redundancies would mean having more time in-between flights, with extra planes and extra mechanics and spare parts available at many airports. Clearly, airlines’ already brittle business model would crumble in a heartbeat.

The flipside efficiency is Taleb’s redundancy. Without optimization, we constantly use more than we need, effectively operating as a tax on all activity. Taleb would of course quibble with that, pointing out that the probability distribution of what “we need” must include Black Swan events that standard optimization arguments overlook.

That’s fine if one places as high a value on risks that Taleb does, and indeed they’re voluntarily paid for. If customers wanted to pay triple the money for airfares in order to avoid this or that delay, there is a market for that – it just seems few people value that price over the damage from (low-probability) delays.

Another example is earthquake-proving buildings that Nate Silver discussed in his The Signal and the Noise regarding the Gutenberg-Ritcher law (the reliably inverse relationship between frequency and magnitude of earthquakes). Constructing buildings that can withstand a high-magnitude earthquake, say a one-in-three-hundred-year event is something rich Californians or Japanese can afford – much-less so a poor country like the Philippines. Yes, Taleb correctly argues, the poor country pays its earthquake expenses in heightened risk of devastating damage.

Large redundancies, back-ups to back-ups, are great if you a) can afford them, and b) are risk-averse enough. Judging by his writing, Taleb is – ironically – far out along the right-tail of risk aversion; for most other people, we have more urgent needs to look after. That means occasionally “blowing up” and suffer hours and hours of airline delays or collapsing buildings after an earthquake.

Taleb rarely considers the trade-offs, and the different subjective value scales (or discount rates!) that differ between people. While Taleb may cherish his redundancies, most of us would rather eliminate them for asymmetrically small gains.

Insurance is a relative assessment of price and risks. Keeping a reserve of redundancies are subjective choices, not an objective necessities.

Nightcap

- California’s fires (no mention of “property rights”) Claire McEachern, LARB

- Nationalism is not always the enemy of liberalism Asle Toje, American Interest

- Universal Love, said the Cactus Person Scott Alexander, Slate Star Codex

- Great list of recent low budget sci-fi flicks Nick Nielsen, Grand Strategy Annex

Changing the way doctors see data

Over the past four years, my brother and I have grown a business that helps doctors publish data-driven articles from the two of us to over 30 experienced researchers. However, along the way, we noticed that data management in medical publication was decades behind other fields–in fact, the vital clinical outcomes from major trials are generally published as singular PDFs with no structured data, and are analyzed in comparison to existing studies only in nonsystematic, nonupdatable publications. Effectively, medicine has no central method for sharing or comparing patient outcomes across therapies, and I think that it is our responsibility as researchers to present these data to the medical community.

Based on our internal estimates, there are >3 million published clinical outcomes studies (with over 200 million individual datapoints) that need to be abstracted, structured, and compared through a central database. We recognized that this is a monumental task, and we therefore have focused on automating and scaling research processes that have been, through today, entirely manual. Only after a year of intensive work have we found a path toward creating a central database for all published patient outcomes, and we are excited to debut our technology publicly!

Keith recently presented our venture at a Mayo Clinic-hosted event, Walleye Tank (a Shark Tank-style competition of medical ventures), and I think that it is an excellent fast-paced introduction to a complex issue. Thanks also to the Mayo Clinic researchers for their interesting questions! You can see his two-minute presentation and the Q&A here. We would love to get more questions from the economic/data science/medical communities, and will continue putting our ideas out there for feedback!

Nightcap

- We’re told Americans have no free time, yet we’re watching more than four (4) hours of TV per day Ryan McMaken, Power & Market

- “A Household God in a Socialist World” [pdf] Andrei Znamenski, Ethnologia Europaea

- Why the world is in uproar right now Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Sex recession? Maybe not… Frances Woolley, Worthwhile Canadian Initiative

Sunday Poetry: Junger’s War Observations

Without noticing it, I heavily built my reading schedule this year around of what one might call a “post-liberal reading list”. The idea, that the demise of social institutions might be the inevitable consequence of an ongoing individualization of society struck me as initially convincing. I am currently in search of good examinations on the ultimate effect Liberalism has on the development of social institutions. Hopefully, Steven Horwitz’ “Hayek’s Modern Family” will provide me with some compelling arguments to refute the post-liberal agenda.

Not directly being post-liberal, but pointing towards the importance of “homecoming and belonging”, Sebastian Junger’s book “Tribe” has had a lasting influence on me. I found the following observations of a war refugee voluntary reentering Sarajevo during its siege both fascinating and devastating.

“What catastrophes seem to do – sometimes in the span of a few minutes – is to turn back the clock on ten thousand years of social evolution. […]

“‘I missed being that close to people. I missed being loved in that way’, she told me. ‘In Bosnia – as it is now – we don’t trust each other anymore; we became really bad people. We didn’t learn the lesson of the war, which is how important it is to share everything you have with humans being close to you. The best way to explain it is that the war makes you an animal. We were animals. It’s insane – but that’s the basic human instinct, to help another human being who is sitting or standing or lying close to you.’

I asked Ahmetašević if people had ultimately been happier during the war.

‘We were the happiest,’ Ahmetašević said. Then she added: “And we laughed more.'”

I wish you all a pleasant Sunday.

Nightcap

- Why the early German socialists opposed the world’s first modern welfare state Adam Sacks, Jacobin

- Russia’s twin Soviet nostalgias Anna Nemtsova, Atlantic

- Is our economists learning? Ryan Cooper, American Prospect

- An excellent history of China in Ghana Joseph Hammond, Diplomat

Psychedelics versus modern philosophy

Anyone who studies philosophy has run into the assumption that psychoactive drugs and philosophy go hand-in-hand. Really, after analytic and continental, and whatever other traditions people come up with, there could be another sect, that of “stoner philosophy,” which is something like Mister Rogers, Alan Watts and Bob Ross thrown into a peaceful blender. This is when you’re sitting around getting high, wondering if aliens exist, instead of sitting in a classroom, wondering if other people’s minds exist.

A historical study of this connection, from East to West, would probably scandalize a lot of “serious” philosophers, and show some regular inebriation, but in general, I think the two are opposed (tragically or not). Particularly, the institutionalization of philosophy, when “natural philosophy” and “moral philosophy” etc all became separated some time after Hobbes, is opposed to what it sees as a lay way of thinking about the world. As my philosophy of science professor told me – you become a philosopher when you have your doctorate.

Professional philosophers and “psychonauts” are in opposition to each other. The analytics and continentals have spent centuries building elaborate systems – developing monstrous levels of specificity, so as to make their work completely incomprehensible to the rest of the world – and earning credentials to close the gates of access. Meanwhile, the casual or professional tripper is able to buy a tab for less than $10 and experience, or imagine they experience, market-price existentialism without reading a page of Camus.

The professional philosopher sneers in bad faith at psychedelic profundity because it makes them seem irrelevant.

On the other hand, the inarticulate tripper is not in such a great place. The psychonaut rests on intuition, and is probably not equipt with the critical thinking and logical itinerary to make sense of the journey on the comedown. A trip promises insight but also promises that neither your epistemic priors nor a rational reconstruction will be enough to establish its validity – by its very nature. (Psychedelic knowledge is “revealed,” not “discovered,” right?) You might get an insight that looks good, but is bad, without you knowing it. (I wrote about this in college. Holy shit my writing was bad.)

What happens when you irrationally, psychonautically attach to an idea that’s immune to logical tinkering? If you believe something for irrational reasons you’ll hang on to it for even longer than something that you believed for rational reasons, because new rational reasons can talk you out of a logogenetic idea, but not an irrationally-formed one. Depending on the centrality of the belief, of course.

The psychonaut claims easy knowledge, but could have trouble organizing it in the other, orderly web of belief of his coldly-discovered priors. However, this kind of knowledge has taken a high prestige today, with help from accredited social figures like Steve Jobs dosing LSD. In a way, the win of casual inebriated profundity is a “people’s victory” over the esoteric, pretentious toils of the professional philosophers. If you can figure out Truth by serotonin-fucking yourself on any day of the week then there’s no need to study Heidegger… and there’s even less reason to get a PhD in phenomenology, making institutional philosophy obsolete.

So, philosophers will be opposed to the psychonauts because it trivializes their hard-earned degrees (bad faith), and trivializes all their carefully crafted logic (slightly less bad faith). Psychonauts will be opposed to the philosophers for their specialized field which must explicitly reject such spontaneous routes to knowledge. The people taking psychedelics find themselves fighting some sort of anti-scientific elitism war, doing Feyerabend’s work. The tension is worse with the professional, modern philosophical class, but still exists in general.

A survey of history would show a lot of intertwining, but ultimately, I think the newer age of philosophy has a lot more overlap with other drugs than psychedelics (specifically Epicurean as opposed to elucidatory drugs, e.g. Adderall, analgesics, cocaine) — which is its own interesting question.

Nightcap

- The pernicious legacy of Vladimir Lenin Gary Saul Morson, New Criterion

- Mendacious fictions: left-wing anti-Semitism Rahul Rao, Disorder of Things

- Virtue signalling and vice signalling John Quiggin, Crooked Timber

- The GOP’s civil war continues to rage on Fred Barnes, Modern Age

Politics according to the Bible

Yeah, let’s go for a topic that is generally polemic. What I’m going to present here will not be exhaustive, but at least I believe it’s a fair and honest (although very breathy) treatment on the topic.

First things first, I believe that the Bible is the Word of God. I believe it was written by people (very likely all men) who were inspired by God. This means that the Bible is not their book. It’s God’s book. Also, although it was written in contexts and cultures very different from ours today, it is still true because it speaks of things that are eternal. So, with that in mind, here are some things I believe the Bible teaches on politics.

The whole Bible is a story of creation, fall, redemption and restoration. God created the World “very good”. However, man fell from this status when he sinned. Sin is to disobey God’s law or to fail to conform to it. When the first man, Adam, sinned, we all sinned, because Adam was our federal representative. It may sound unfair that we are all punished for something that someone else did, but students of politics shouldn’t be surprised. We suffer (or benefit) from things we didn’t do all the time. In this particular case, God chose Adam as humanity’s representative. God is just. It was a just choice. After Adam fell, Jesus became the federal representative of a part of humanity that God decided to save. This is the “redemption”. The restoration is God reversing the effects of the fall through the church.

The whole Bible story can be summarized as “kingdom through covenant”. A covenant is a solemn agreement between at least two (not necessarily equal) parties, involving promises and sanctions. God made a covenant with Adam. Adam broke that covenant. God made a covenant with Jesus. Jesus fulfilled the covenant. By fulfilling it, Jesus became the king of a people, the church.

Jesus’ covenant was anticipated by some covenants in what we call the Old Testament. Although the theories vary, the point is that God’s covenants with Noah, Abraham, Moses and David somehow anticipate Jesus. This means that in the Old Testament God’s people was mostly one nation, Israel, organized as a nation-state. This nation-state had civil laws. One great mistake is to try to apply these civil laws to any state today. Israel was an anticipation of the real people of God, the church. The church is not a nation-state. It doesn’t have civil laws. Actually, Jesus repeatedly said that his kingdom was not of this world, meaning that it would not be brought by political force.

The fact that Israel was an anticipation of the true church doesn’t mean that all the laws given to Israel are irrelevant today. The moral law given in the 10 commandments is still biding. even the civil laws, although no longer bidding, can be informative. The point is that these laws cannot be enforced by any state. They have to be preached. People must be left free to join. Or not.

What the church can expect from the state? It would certainly be great to live in a country that fully conforms to God’s moral law, but this is not a realistic expectation. The best we can expect is a state that keeps people free to decide whether they want to join the church or not. Other than that, there is a moral law that we all can benefit from: don’t hurt others and don’t pick their stuff without permission.

Trying to enforce God’s kingdom was one of the greatest mistakes Christians committed through the centuries, and I believe many Christians are still doing it today. We want people to be Christians not out of their free choice, but by coercion. Or we want people to externally behave as Christians when they are not. Again: the best we can do is to let people free to decide. And meanwhile, demand that we are also free to practice our religion, no matter what other people think about it.

Nightcap

- Fear and loathing at the NATO summit? Curt Mills, American Conservative

- The Russians are in Libya now, too Frederic Wherey, Foreign Policy

- Is the 21st century really about US-China? Will Staton, Areo

- The opioids have been nothing but good to us Steven Landsburg, Big Questions

Nightcap

- Can we still learn from Lincoln? Forrest Nabors, Law & Liberty

- On Brexit and beyond Lionel Barber, Financial Times

- On Morocco’s most revered leftist Khalid Lyamlahy, Los Angeles Review of Books

- 2015: France’s bad year Andrew Hussey, Literary Review

Nightcap

- Slowly, a civil war on the left brews Ryu Spaeth, New Republic

- African Catholics David Whitehouse, Imperial & Global Forum

- Geniuses don’t have to be nice Richard Evans, TLS

- The great American banking myth George Selgin, Alt-M

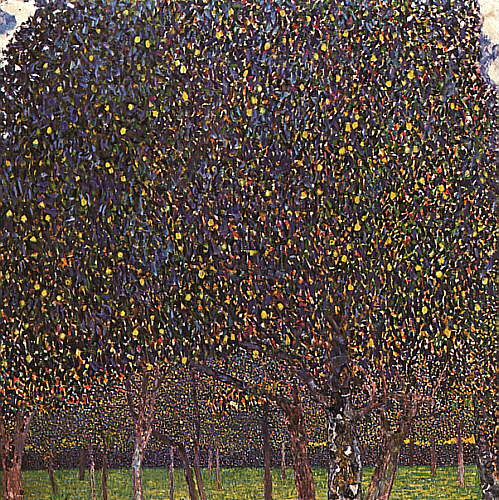

Afternoon Tea: Pear Tree (1903)

This is from Gustav Klimt, my favorite artist of all time. Click here to zoom. I just started getting in to his “nature” stuff. He and Egon Schiele made cool landscapes. Have a good rest of the day!

Nightcap

- Rocky Mountain states continue to produce excellent governors Epstein & Stevens, New York Times

- Blood and soil in Narendra Modi’s India Dexter Filkins, New Yorker

- David Graeber against economics David Glasner, Uneasy Money

- Libertarians and pragmatists on democracy Zak Woodman, NOL