This is about: “Rethinking the State: Genesis and Structure of Bureaucracy.” [link] Pierre Bourdieu has not known what he was talking about as long as I have been an adult. He is equal to himself; he still does not. His talent – that he shares with many French intellectuals – is to persuade others to pretend that they do understand. Don’t take my word for it. Read the opening sentence of the current piece and ask yourself honestly what it means. And no, don’t blame the translation. I have not read this piece in the original French but I have read many opening statements in French by Bourdieu and, they are worse. (I am competent to read French including “sociologie.” ) In fact, I wouldn’t be surprised if the translators had actually improved the first sentence in this particular piece. Another thing about contemporary French social scientists (but not historians) is that it’s seldom quite clear what the relationship is – if any – between their narrative and facts on the ground. Don’t get me started!

I Don’t Want to Fight to the Last Ukrainian

I hope the brave Ukrainians will soon decide to stop dying. I seems to me they have to. The Russians have demonstrated that their armed forces are too incompetent to conquer Ukraine and to reduce it to a satellite. Their capacity to bomb and pound whole cites into a fields of rubble, however, is not in doubt. Even if the Ukrainians managed to expel all Russian troops from all of their country, the Russians could still destroy most Ukrainian cities from their own territory. It does not take much talent if you don’t mind the expense of throwing the same missiles over and over against the same large targets. And the expense may not matter so much while several NATO countries are still paying their fossil fuel bills to the Kremlin. And, if the Ukrainians succeeded in bringing the war to Russia itself to make the attacks cease, they would immediately face a measure of abandonment by world public opinion, including by NATO countries. In addition, even a slight invasion of Russia would probably trigger a wave of self-righteous Russian patriotism. The reluctant Russian soldiers and sailors we have seen in largely pathetic action thus far might soon be replaced by enthusiasts eager to sacrifice themselves for the motherland.

It seems to me the Ukrainians have established they are able to preserve their independence and their recently earned democracy. Yet, it appears that Pres. Zelenskyy has announced his government’s determination to boot every armed Russian from every square inch of Ukrainian soil. Such a project involves going on the offensive against an entrenched enemy because the Russians have been present in the Dombas eastern region, in some guise or other, since 2014. Attacking an entrenched enemy is always very costly in lives as the Russian military’s own failed attempt to take the Ukrainian capital showed anew. I hear in the mass media military experts of diverse nationalities assert that it takes many tanks, among other equipment, and mastery of the skies. The Ukrainians have few of the first and little hold over the other. So, the Ukrainian president’s inflexibility is a signal that many more Ukrainians will die. I can’t help but wonder why it should be so, or what for, except that Zelenskyy may be making the bet that the Russian invaders will soon fold and retreat from every area that was Ukrainian in 2013. Zelenskyy may know things I don’t know, of course but from where I sit, in the calm, his attitude seems unnecessarily dangerous. Let me explain.

After eight years of war – even if most was low intensity war – a good half of the Donbas region, most of its cities, including the puppet “people’s republics” of Donetsk and Luhansk, is probably inhabited almost entirely by Russian speakers who are pro-Russians. The others must have left long ago or been driven out. Making the existing pro-Russia population of Donbas submit would place the current elected Ukrainian government in the same situation as the Russians now are in some other parts of Ukraine: occupiers, hated, unable to reduce the local population’s resistance, liable to commit atrocities out of sheer frustration. The currently virtuous Ukraine Republic could quickly be transformed into the kind of vicious monster it is now facing on the rest of its territory.

The prized Crimean peninsula was annexed outright by Russia in 2014, soon after it was seized, and following a questionable referendum. However, since its annexation there have been few protests there against Russia. I don’t think there is a pro-Ukrainian popular movement in the Crimea. (I believe that if there were, I would have heard of it. Correct me if I have been inattentive.) It’s also good to remember that the ties between Crimea and Ukraine may well be historically shallow. Khrushchev gave it to the Ukraine Soviet Republic in 1954 (yes, 1954) pretty much as a gift. In the 2001 count, the last conducted under Ukrainian rule, only 24% of Crimeans were identified as Ukrainians. It’s notable that in the several years between the Russian annexation and the current invasion of Ukraine, it seems there have been few serious statements by any country, including Ukraine, to the effect that the latter had to be reversed. (Correct me if I am wrong.)

As I write (4/26/22) Ukraine’s military position appears strong but it’s facing an offensive where Russia’s military inferiority may not compensate for Ukraine’s smaller numbers and lack of heavy materiel and airplanes. This is the right time to make peace proposals. It appears that Putin is not the kind of person who will admit defeat or even that his project was ill-thought out and ill-planned. Even if he is not actually insane – which have has been suggested by several credible sources – an oblique approach seems well advised here This might be done, perhaps by asking various Russian oligarchs – who stand to lose even more by continued hostilities – to contact Russian general officers who are probably not eager to be dragged further in a reputational mud hole, or who might want to save what’s left of their army.

I think a peace agreement would grant Russia control of all of the Donbas which again – it had already mostly under its control – and an extension south through devastated Mariupol to form a land bridge between Russia proper and Crimea. Some of the arguments against such a resolution smack of the 19th century. First, President Zelenskyy speaks of the territorial integrity of his country as if it were a sacred concept. Yet, we know of a number of countries that lost territory and subsequently did well in every way. At the end of WWII, for example, Germany was amputated of about ¼ of its territory. Yet, it emerged in insolent health ten years later.

A main objection to Ukraine relinquishing the Donbas is that it’s its most industrialized section. This sounds like more 19th century thinking. The Donbas has a considerable steel industry and a heavy metallurgical industry because it also possesses coal mines (with coal difficult and expensive to mine). This raise the question of whether the country should exchange the lives of many of its young men again an energy source that seems to be on its way out anyway and the kind of associated heavy manufacturing favored by Stalin. The examples of Singapore and of geographically nearer Switzerland come to mind. Both countries maintain a superior standard of living without the benefit of either rich energy sources or of conventional metal-based manufacturing. These examples make it easy to argue that the real riches of a country may be its people rather than so many million tons of coals. One more reason to be stingy with Ukrainians’ lives.

If the Ukrainian government made what it probably now thinks of as the sacrifice to sue for peace immediately or soon, it would gain a big prize. I mean that it would be able to keep the big port city of Odesa which is now almost intact. With Odesa, the Ukraine would retain a single access to the sea which is probably more important economically than any coal mines. Odesa was about 2/3 Ukrainian in the last count with Russians making up less than one third. It does not pose the same kind of retention problems as Donbas.

One last but major consideration. The Ukrainian government is fond of affirming that its country is fighting for all of us, not just for itself, against Russian totalitarianism and aggression. This is an almost necessary argument to prime the military and economic pump from the West. It may even be partially true. Yet, right now, – and paradoxically not a little thanks to Putin’s wake-up call- it’s pretty clear NATO can take care of its own. I mean this, even given the lightly brandished nuclear threat. I am pretty sure the Russian General Staff has in its possession a list of its military installations that would be wiped out in the first round of riposte to a nuclear event, a second list of fossil fuel extraction and transformation sites that would be gone on the second round, and a list of Russian cities that would suffer the fate of Mariupol on the third.

I think NATO has the means to return Russia to the Third World status it ever only barely escaped. I also think the Russian military knows this. So, I am very much against the possibility of the West fighting for its freedom and for its prosperity to the last Ukrainian. That’s so, even if the Ukrainians insist they would like too. I am filled with horror at the thought of being even a smidgen responsible for making even more Ukrainian orphans and widows.

And yes, the peace I envision would be another form of rewarding aggression. However, in this case, there is a good trade-off. Russia would acquire some industrial territory in the old mold at the cost of having demonstrated to the world a surprising degree of military incompetence. We, in the US, should keep supporting the Ukrainian war effort just to say “Thanks” for this demonstration.

Nightcap

- “The Rise of the Bureaucratic State” (pdf) James Q Wilson, Public Interest

- “Rethinking the State: Genesis and Structure of Bureaucracy” (pdf) Pierre Bourdieu, ST

- “State Capacity, Bureaucratic Politicization, and Corruption” (pdf) Katherine Bersch, et al, Governance

- Why are skyscrapers so short? Brian Potter, Works in Progress

Some Monday Links

Science fiction, cont.

Jobs and Class of Main Characters in Science Fiction (Vector)

Steampunk: How this subgenre of science fiction challenges the beliefs of civilisational progress (Scroll)

Have yet to actually read a steampunk book, Mistborn notwithstanding. Was about to buy “The Difference Machine”, but last minute I opted for the history/ fiction hybrid of “Red Plenty” (one of the books I keep returning to, btw, very rewarding read).

Presidents as Economic Managers (National Affairs)

Nightcap

- “The ‘Four Gods’ in Maximum Security Prison” (pdf) Sung Joon Jang, et al, RRR

- “Leisure, satisfaction, happiness, and religion” (pdf) Huimei Liu, et al, Leisure Studies

- Cairo’s “City of the Dead” is being razed Vivian Yee, New York Times

- Government and religion in the United States (pdf) James Q Wilson, BR

Nightcap

- London Calling: H.L.A. Hart on place names Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Use and abuse of the Temple Mount Michael Koplow, Ottomans & Zionists

- People can collaborate in free markets too Johnathan Pearce, Samizdata

- Brainwashing is sorcery Robin Hanson, Overcoming Bias

Nightcap

- “A Political Theory of Empire and Imperialism” (pdf) Jennifer Pitts, ARPS

- Tyler Cowen interviews Thomas Piketty

- “The Foundations of American Internationalism” (pdf) David Hendrickson, Orbis

Some derivations from the uses of the terms “knowledge” and “information” in F. A. Hayek’s works.

In 1945, Friedrich A. Hayek published under the title “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” in The American Economic Review, one of his most celebrated essays -both at the time of its appearance and today- and probably, together with other studies also later compiled in the volume Individualism and Economic Order (1948), one of those that have earned him the award of the Nobel Prize in Economics, in 1974.

His interpretation generates certain perplexities about the meaning of the term “knowledge”, which the author himself would clear up years later, in the prologue to the third volume of Law, Legislation and Liberty (1979). Being his native language German, Hayek explains there that it would have been more appropriate to have used the term “information”, since such was the prevailing meaning of “knowledge” in the years in which such essays had been written. Incidentally, a similar clarification is also made regarding the confusions raised around the “spontaneous order” turn, which he later replaced by that of “abstract order”, with further subsequent replacements:

“Though I still like and occasionally use the term ‘spontaneous order’, I agree that ‘self-generating order’ or ‘self-organizing structures’ are sometimes more precise and unambiguous and therefore frequently use them instead of the former term. Similarly, instead of ‘order’, in conformity with today’s predominant usage, I occasionally now use ‘system’. Also ‘information’ is clearly often preferable to where I usually spoke of ‘knowledge’, since the former clearly refers to the knowledge of particular facts rather than theoretical knowledge to which plain ‘knowledge’ might be thought to prefer” . (Hayek, F.A., “Law, Legislation and Liberty”, Volume 3, Preface to “The Political Order of a Free People”.)

Although it is already impossible to substitute in current use the term “knowledge” for “information” and “spontaneous” for “abstract”; it is worth always keeping in mind what ultimate meaning should be given to such concepts, at least in order to respect the original intention of the author and perform a consistent interpretation of his texts.

By “the use of knowledge in society”, we will have to refer, then, to the result of the use of information available to each individual who is inserted in a particular situation of time and place and who interacts directly or indirectly with countless of other individuals, whose special circumstances of time and place differ from each other and, therefore, also have fragments of information that are in some respects compatible and in others divergent.

In the economic field, this is manifested by the variations in the relative scarcity of the different goods that are exchanged in the market, expressed in the variations of their relative prices. An increase in the market price of a good expresses an increase in its relative scarcity, although we do not know if this is due to a drop in supply, an increase in demand, or a combined effect of both phenomena, which vary joint or disparate. The same is true of a fall in the price of a given good. In turn, such variations in relative prices lead to a change in individual expectations and plans, since this may mean a change in the relationship between the prices of substitute or complementary goods, inputs or final products, factors of production, etc. In a feedback process, such changes in plans will in turn generate new variations in relative prices. Such bits of information available to each individual can be synthesized by the price system, which generates incentives at the individual level, but could never be concentrated by a central committee of planners. In the same essay, Hayek emphasizes that such a process of spontaneous coordination is also manifested in other aspects of social interactions, in addition to the exchange of economic goods. They are the spontaneous –or abstract- phenomena, such as language or behavioral norms, which structure the coordination of human interaction without the need for a central direction.

“The Use of Knowledge in Society” appears halfway through the life of Friedrich Hayek and in the middle of the dispute over economic calculation in socialism. His implicit assumptions will be revealed later in his book The Sensory Order (1952) and in the already mentioned Law, Legislation and Liberty (1973, 1976 and 1979). In the first of them, we can find the distinction between relative limits and absolute limits of information / knowledge. The relative ones are those concerning the instruments of measurement and exploration: better microscopes, better techniques or better statistics push forward the frontiers of knowledge, making it more specific. However, if we go up in classification levels, among which are the coordination phenomena between various individual plans, which are explained by increasingly abstract behavior patterns, we will have to find an insurmountable barrier when configuring a coherent and totalizer of the social order resulting from these interactions. This is what Hayek will later call the theory of complex phenomena.

The latter was collected in Law, Legislation and Liberty, in which he will have to apply the same principles enunciated incipiently in “The Use of Knowledge in Society” regarding the phenomena of spontaneous coordination of individual life plans in the plane of the norms of conduct and of the political organization. Whether in the economic, legal and political spheres, the issue of the impossibility of centralized planning and the need to trust the results of free interaction between individuals is found again.

In this regard, the Marxist philosopher and economist Adolph Löwe argued that Hayek, John Maynard Keynes, and himself, considered that such interaction between individuals generated a feedback process by itself: the data obtained from the environment by the agents generated a readjustment of individual plans, which in turn meant new data that would readjust those plans again. Löwe stressed that both he and Keynes understood that they were facing a positive feedback phenomenon (one deviation led to another amplified deviation, which required state intervention), while Hayek argued that the dynamics of society, structured around values such like respect for property rights, it involved a negative feedback process, in which continuous endogenous readjustments maintained a stable order of events. Hayek’s own express references to such negative feedback processes and to the value of cybernetics confirm Lowe’s assessment.

Today, the dispute over the possibility or impossibility of centralized planning returns to the public debate with the recent developments in the field of Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things and genetic engineering, in which the previous committee of experts would be replaced by programmers, biologists and other scientists. Surely the notions of spontaneous coordination, abstract orders, complex phenomena and relative and absolute limits for information / knowledge will allow fruitful contributions to be made in such aspects.

It is appropriate to ask then how Hayek would have considered the phenomenon of Artificial Intelligence (A.I.), or rather: how he would have valued the estimates that we make today about its possible consequences. But to adequately answer such a question, we must not only agree on what we understand by Artificial Intelligence, but it is also interesting and essential to discuss, prior to that, how Hayek conceptualized the faculty of understanding.

Friedrich Hayek had been strongly influenced in his youth by the Empirical Criticism of his teacher Ernst Mach. Although in The Sensory Order he considers that his own philosophical version called “pure empiricism” overcomes the difficulties of the former as well as David Hume’s empiricism, it must be recognized that the critique of Cartesian Dualism inherited from his former teacher was maintained by Hayek -even in his older works- in a central role. Hayek characterizes Cartesian Dualism as the radical separation between the subject of knowledge and the object of knowledge, in such a way that the former has the full capabilities to formulate a total and coherent representation of reality external to said subject, but at the same time consists of the whole world. This is because the representational synthesis carried out by the subject acts as a kind of mirror of reality: the res intensa expresses the content of the res extensa, in a kind of transcendent duplication, in parallel.

On the contrary, Hayek considers that the subject is an inseparable part of the experience. The subject of knowledge is also experience, integrating what is given. Hayek, thus, also relates his conception of the impossibility for a given mind to account for the totality of experience, since it itself integrates it, with Gödel’s Theorem, which concludes that it is impossible for a system of knowledge to be complete and consistent in terms of its representation of reality, thus demolishing the Leibznian project of the mechanization of thought.

It is in the essays “Degrees of Explanation” and “The Theory of Complex Phenomena” –later collected in the volume of Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, 1967- in which Hayek expressly recognizes in that Gödel’s Theorem and also in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s paradoxes about the impossibility of forming a “set of all sets” his foundation about the impossibility for a human mind to know and control the totality of human events at the social, political and legal levels.

In short, what Hayek was doing with this was to re-edit the arguments of his past debate on the impossibility of socialism in order to apply them, in a more sophisticated and refined way, to the problem of the deliberate construction and direction of a social order by part of a political body devoid of rules and endowed with a pure political will.

However, such impossibility of mechanization of thought does not in itself imply chaos, but on the contrary the Kosmos. Hayek rescues the old Greek notion of an uncreated and stable order, which relentlessly punishes the hybris of those who seek to emulate and replace the cosmic order, such as the myth of Oedipus the King, who killed his father and married his mother, as a way of creating himself likewise and whose arrogance caused the plague in Thebes. Like every negative feedback system, the old Greek Kosmos was an order which restored its lost inner equilibrium by itself, whose complexities humiliated human reason and urged to replace calculus with virtue. Nevertheless, what we should understand for that “virtue” would be a subject to be discussed many centuries later from the old Greeks and Romans, in the Northern Italy of the Renaissance.

Nightcap

- “The orthodox treatment of [national] defense as a pure public good that must be provided by a centralized state suffers from three key issues.” (pdf) Coyne & Goodman, TIR

- Mosquito-Relish Diplomacy: Hill-Versus-Valley Dynamics in China and Thailand (pdf) Cushman & Jonsson, Journal of the Siam Society

- An International Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States (pdf) Max Edling, Past and Present

- The End of Empire and the Extension of the Westphalian System (pdf) Hendrick Spruyt, International Studies Review

Nightcap: Primitive communism

I should be jealous of Manvir Singh. He’s an anthropologist who publishes stuff in the academic and popular press. The stuff he publishes is the stuff I am interested in. It’s the stuff I would have published if I had gone into academia. I’m not jealous, though. I’m on the path that I’m meant to be on. And I would never have gotten away with popularizing this:

Hunters’ privileges are inconvenient for narratives about primitive communism. More damning, however, is a starker, simpler fact. All hunter-gatherers had private property, even the Aché.

“What’s in a name?”

The following piece was first published in my personal newsletter. I am sharing it with the NOL community as introduction to displays of social ignorance and the role I think it plays in social Marxism.

He may call himself Mr Pelham to his heart’s content. He is Lord Hexam in this house.

~ Downton Abbey

Carson the butler says this in response to learning that Lady Edith Crawley’s husband, Mr. Bertie Pelham, has just inherited the Marquessate of Hexam from a cousin. Bertie doesn’t want to assume the title until his cousin is buried, but Carson reminds the staff that system of aristocracy doesn’t work like that. The king is dead, long live the king. Mr Pelham is now Lord Hexam whether he wills or not. A little knowledge of the system and possibly a little less cognitive bias might have prevented an embarrassing episode.

Back in March 2021, The Independent issued a small clarification without any fanfare: On 12 March 2021 we published an article headlined: ‘I’m a black British member of the aristocracy. I love the royal family — but I know what Meghan said was true,’ written by Alexander Maier-Dlamini in which he was described as the “Marquess of Annaville – the last of the Irish peerages”. This was incorrect, there is no Marquess of Annaville in the Irish peerage. The article in question ran in the midst of the fallout from the Duke of Sussex and his wife’s interview with Oprah in which they described his family as racists and British and American society as equally racist, just in different ways. In particular Meghan Sussex implied that her son was denied a title due to his mixed-race heritage (he has a title, Earl of Dumbarton: the parents won’t use it.). The Marquess of Annaville threw his weight behind the Sussexes, arguing that he knew they were right because of his personal experiences. However, there is no Marquess of Annaville.

The fake Marquess turned out to be a 22-year old American student from New Rochelle, New York, with very little knowledge of titles, peerages, aristocracy, or manner in which any of those structures worked. The only true things about the man’s claims are that his name is Alexander Maier-Dlamini, his spouse’s last name is Dlamini (which wouldn’t be part of Alexander’s title), and he is Black. Correctly, he is African-American, but that was not his claim: since he purported be a peer of the United Kingdom, by extension he was claiming to be Black British. After Debrett’s proved that there was no Marquessate of Annaville, he confessed to his fraud. In a statement he said, “There is no title in the peerage related to me whatsoever. I do apologize greatly to those institutions involved with a mechanism like this, many of which I’m obviously not familiar with.” “Not familiar with” is an understatement.

The fact that The Independent ran this man’s op-ed represents an appalling lack of due diligence. The Independent quietly deleted the article, but not before I and a horde of netizens read it. In almost no time, other publications and the general public established that there was no Marquessate of Annaville, a fact that the newspaper could have been checked by a quick search of Debrett’s online database, or Burke’s Peerage database. These two resources both require subscriptions to access the databases, but considering The Independent is a major publication, it is reasonable to expect them to pay for such things as part of basic due diligence. But there were other tells which make the fact that no search was done on the fake marquess inexcusable.

He signed his article “Lord Alexander Maier-Dlamini, Marquess of Annaville.” This is a mix of forms. The first, “Lord Alexander Maier-Dlamini,” is the form for a younger son, and it is incorrect to use this for the peer, i.e. the holder of the title. Alexander Maier-Dlamini claimed to be the Marquess, and therefore would be the peer. The correct form for the peer is either: 1) Alexander Maier-Dlamini, Marquess of Annaville, or 2) Lord Annaville. This is very basic information that is part of simply being socially aware and is freely available. Back when I was interning at AEC in Vienna, Debrett’s website provided free information on the etiquette of writing titles. The fact that The Independent didn’t catch Maier-Dlamini’s incorrect use of form is beyond me.

According to one of the netizens who helped catch him, even after apologizing for his fraud, Maier-Dlamini continued to publish as a fake aristocrat under the name “Lord Zigmund Annaville,” purportedly the brother of “Lord Alexander.” There are two things to notice that are wrong: 1) “Zigmund” is a phonetic spelling of the German “Sigmund,” and while it has been used historically, it has not been used in mainstream European society since at least the 1800s; an aristocratic family is unlikely to make that mistake; 2) Annaville is the peerage, not the family name, so a younger son would not use it. Peers and their wives (but not the husbands of female peers) may use their peerage as their last name. So it is correct to refer to Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge as Catherine Cambridge. It would not be correct to call her younger son, Prince Louis of Cambridge, “Louis Cambridge.” If Lord Zigmund really existed, his correct form would be “Lord Zigmund Maier.” He would use the family name.

As a commentator at the time pointed out in an article I haven’t been able to find, claiming to be the 11th Marquess should have been enough to trigger red flags with the people over at The Independent. Assuming an average of three generations per century (father, son, grandson), the peerage would have been created around the 1600s, possibly even earlier, and the family could potentially be much older. Marquesses tend to be senior peers of whatever realm they are in, so therefore it is impossible for no one to have heard of a Marquess of Annaville if the title really existed. Given the presence of the aristocracy in British history, the Marquesses of Annaville or other members of the Maier family would have been all over the history books. For a comparison, the 11th Duke of Marlborough died in 2014. The Dukedom was created in 1689 as an upgrade for the then-Earl of Marlborough. The Churchill family (they re-hyphenated their name to Spencer-Churchill in the mid-twentieth century) is one of the most storied in British history, having produced Sir Winston Churchill, who was never confused about whether he was Winston Churchill or Winston Marlborough. He easily could have been: when he was born, he was second in line behind his father Lord Randolph Churchill. Fortunately for history, the 8th Duke married late in life and had a son; if he had not, Winston could have been the duke in World War II and as a peer would have been barred from becoming Prime Minister. From what I know, Lord Randolph Churchill and Winston were a little squiffy when their brother and uncle’s new wife produced a son, who effectively destroyed their hopes of acceding to the title. Perhaps one can attempt to be charitable and assume that Alexander Maier-Dlamini thought peerages worked like the U.S. presidency: the incumbent vacated after at most eight years. Hypothetically, this could explain why the Annaville title was so far along in holders but no one could remember the incumbent’s predecessors.

As part of his op-ed, Maier claimed that he was constantly having to explain his lineage and how he came to be a marquess as no one believed a Black man could be a titled aristocrat. In doing so, he revealed the time contradiction — if the Annaville title was an old one, everyone would have remembered his father’s marriage to his mother when it was announced twenty some-odd years ago. No, this is not an assumption; in order for a son to inherit his father’s titles, the father has to have been married to the mother at the time of the child’s birth, otherwise the child is illegitimate and cannot claim his father’s titles. A marriage for someone as important as a Marquess would have been announced in the major newspapers. Of course Maier-Dlamini also revealed his ignorance of the existence of the Black and other minority life peers sitting in the House of Lords in Parliament.

For the other part of his claim that people racially profiled him, it is believable that that detail missed vetting given how many people seem to be unaware that there are plenty of people of African or other minority descent married into the British aristocracy, in addition to the ones holding peerages in their own rights. The Marchioness of Bath, wife of the 8th Marquess, is the daughter of an Oxford-educated Nigerian chief. Her words in response to questions about being a Black marchioness were, “I see my role as a practical thing: as a wife, mother and someone with a responsibility to maintain this incredible estate. I aspire to a future where [my skin colour] is not a defining characteristic.” Lord Mountbatten’s great-granddaughter and first cousin twice removed (granddaughter of first cousin) of Prince Philip is married to a Black man, with whom she has three children. She and they are in the line of succession for both the Earldom of Burma and the British throne. She put up a picture of her children and grandmother, Lady Pamela Hicks, Lord Mountbatten’s second daughter on Instagram in April 2021, a month after The Independent ran its fake story.

There’s probably no connection, but one wonders. And lest anyone think that it’s African-Americans who seem to have trouble with the British aristocracy, indisputably Black American Candace Owens is married to the Honourable George Farmer, son of Michael Farmer, Baron Farmer. Owen’s and Farmer’s son is a mixed-race member of the aristocracy. Her retort in response to issues of titles and race was “If you have seen a picture of Archie and you believe he suffered anti-black racism, then call me a Nigerian prince and give me your credit card number.” In claiming racist profiling, Alexander Maier-Dlamini revealed that he was unable to transcend the boundaries of his own limitations and concocted stories which might fit the experiences of a young man from New Rochelle, but which reveal that he didn’t do the most basic research on the group of people whose membership he claimed.

Alexander Maier-Dlamini’s failure to research or to understand the intricacies of aristocracy is his own. The Independent giving him a platform is theirs. It would be nice to say that The Independent’s editors suffered from bias confirmation, that psychological condition where because the data appear to fit preformed conclusions, one doesn’t check. The reality, though, is that there were so many signs that Maier-Dlamini was a fraud that there is no explanation for the editors’ failure. Even the most bias-blinded person should be able to stop and say “wouldn’t a real aristocrat know whether he is Lord Annaville or Lord Alexander?” Since the answer is “yes, a real aristocrat would know.” That should have triggered a fact check.

Some Monday Links

Cowboy progressives (Aeon)

Gramsci’s Gift (Boston Review)

A Country of Their Own (Foreign Affairs)

America has captured France (UnHerd)

Why 1980s Oxford holds the key to Britain’s ruling class (Financial Times)

Debt Traps from China, Western Stringency, and the Future of South Asian Democracy

Introduction

If one were to look at two events in South Asia – the economic crisis in Sri Lanka and the downfall of the Imran Khan-led Pakistan Tehreek-E-Insaaf (PTI) government in Pakistan, one of the points which clearly emerges is that both the South Asian nations have moved closer to China, and there are pitfalls to being excessively dependent upon Beijing. Both countries have often been accused of becoming excessively reliant upon China and falling into what has been dubbed as a “debt trap,” which leads not only to rising economic dependency — as a result of piling debts — but also to Beijing dictating political choices.

External debts of Pakistan and Sri Lanka

The International Monetary Fund (IMF), according to estimates in February 2022, had said that Pakistan owe $18.4 billion (or 1/5th) of its external debt to China, while Sri Lanka’s total debt to China is estimated at $8 billion, its total external debt is $45 billion.

In the case of Pakistan, a lot of attention has been focused on Imran Khan’s independent stance on the Ukraine issue, and a possible external hand in his ouster. Yet the Pakistan Democratic Movement (PDM) coalition, led by PML-N Supremo Shahbaz Sharif — which is now in power – has repeatedly pointed to Khan’s mismanagement of the economy and the growing disillusionment of the public as well as erstwhile allies (one of the final blows to Khan’s hopes of staying in power was when the Muttahida Qaumi Movement Pakistan (MQM) pulled out of the PTI alliance) as some of the key reasons for the ouster of the PTI government. While no political party can afford to say it, Pakistan’s dependence upon China has begun to cause concern, especially amongst sections of the business community who are keen to diversify the country’s economic relations.

The dire economic crisis which has hit Sri Lanka has been attributed to multiple factors; economic mismanagement by the government, dip in remittances as well as a fall in tourism as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic and over reliance on China.

Interestingly, while earlier Sri Lanka had refused to seek assistance from the IMF, it has been compelled to, as it is left with limited options. A Sri Lankan team headed by newly-appointed Finance Minister Ali Sabry is headed to Washington DC for negotiations with the Americans. In an interview to Bloomberg television, the Sri Lankan Finance Minister said “‘We need immediate emergency funding to get Sri Lanka back on track.”

If one were to look at the instance of Pakistan, while Islamabad has become increasingly dependent upon China in recent years — especially as a result of its deterioration of ties with the US, and the $64 billion China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project – it has realized that it can not allow its ties with the West to slide further even though close relations with China are imperative. It is not only Western analysts and US policy makers but even ministers in the previous Imran Khan-led PTI government who had actually raised question marks with regard to the economic sustainability of certain CPEC projects. China had expressed its displeasure to Pakistan over the same.

One of the reasons cited for Imran Khan’s differences with the Pakistan army have been his anti-West stance – the former PM accused the US of plotting his downfall and for following an independent foreign policy, pointing to a memo which said that “…if the no-confidence motion passes, Pakistan will be forgiven, if not, there will be consequences.” The US has repeatedly dismissed these charges levelled by Imran Khan.

Khan’s successor, Shahbaz Sharif, has given clear indicators that he will focus on relations with China and Saudi Arabia. He has also hinted at mending ties with the West. US Secretary of State Antony Blinken, in a congratulatory message to the Pakistan PM, said:

The United States congratulates newly elected Pakistani Prime Minister Shahbaz Sharif and we look forward to continuing our long-standing cooperation.

Pakistan is dependent upon the US and EU, since they are important export markets. During his address at the Islamabad Security Dialogue, Pakistan Army Chief Qamar Javed Bajwa, while commenting on Pakistan-US ties, had said: “we share a long and excellent strategic relationship with the US which remains our largest export market.”

Pakistan’s grey list status at Financial Action Task Force (FATF) will also be in review in June 2022. Islamabad would need to mend ties with Western countries if it wants its grey list status to be removed. Pakistan is also likely to resume negotiations with the IMF for the 7th review of the $6 billion loan agreement which was signed with the IMF in 2019. For smooth negotiations with the IMF, a working relationship with Washington DC is essential.

In conclusion, while it is true that Western institutions impose stringent conditions on developing countries and they are compelled to look for different options, excessive dependence upon China has its own pitfalls. It is time for South Asia to look inwards and focus on strengthening regional cooperation and realise that no external player can come up with sustainable solutions for dealing with the region’s economic challenges.

Nightcap

- Putin’s “Century of Betrayal” speech Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Religious discrimination in late imperial Russia Volha Charnysh, Broadstreet

- The future of NATO Jason Davidson, War on the Rocks

- Secession and international alliances go together Edwin van de Haar, NOL

The Federation of Free States: Helping Atlas Shrug

After federating with 51 polities, with one round of peaceful federation happening in 2025 and another in 2045, life in the compound republic got real good, for everyone.

In 2055, diplomats, politicians, and policymakers from the federation began targeting wealthy provinces and countries for membership, a new development that was sparked in part by an alarming rise in despotism (democratic and authoritarian) and in part by stagnant economic growth in the non-Philadelphian interstate order. German, Indian, Brazilian, Italian, and Chinese polities were recruited to join the federation. The Netherlands and the United Arab Emirates were also recruited to join.

The military of the republic is relatively small compared to polities like Russia and China, but far more lethal and technologically advanced, so recruitment was bold. Poaching the rich provinces of second-tier regional powers was not welcomed by the second tiers. They felt bullied. China threatened war, as it did in 2025 when Taiwan joined the federation, but there was nothing the CCP could do about it.

A bunch of separatist regions applied for membership, too. This is probably the most important difference between Westphalian sovereignty and Philadelphian sovereignty. When the Westphalian interstate order was hegemonic, separatists wanted independence; the Philadelphian interstate order gives separatist movements an incentive to join the compound republic instead of trying to go it alone. Westphalian states do not much like the compound republic’s courting of their separatist regions, either.

So between the active courting of wealthy provinces and the active courting of secessionist movements, the stage has been set for a less-than-peaceful round of federating with polities that wish to join the federation of free states.

Many poor states continued to apply for membership, too.

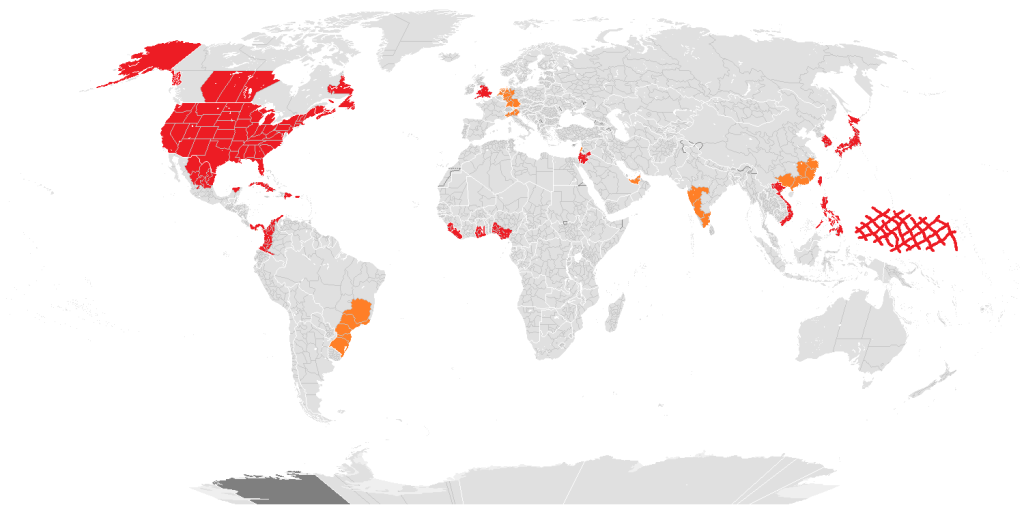

In 2055, here is what the Philadelphian interstate order looks like:

Lagos and Los Angeles joined New York, Tokyo, and London as major financial centers. The people in Canaan, England, and Wales, taking a page out of the Ashanti playbook, let their nationalist sentiments wane to a cultural level rather than a politico-legal level. The people in these “states” had finally come to terms with their place in the Philadelphian interstate order.

The German states of Bavaria, Lower Saxony, North Rhine-Westphalia (how ironic!), Baden-Württemberg, and Rhine-Hesse (a combination of the current states of Hesse and Rhineland-Palatinate) all joined the federation.

The Netherlands joined as is. The Dutch provinces have a long, proud history of republicanism, and it was not an easy choice to make. But by themselves, they were just too small to join the federation, so they banded together a la the Nigerian states of 2045, and joined as a single unit, where they enjoy two Senate seats and roughly the same amount of representatives in Congress as New York or Pennsylvania.

Five Italian provinces joined: Veneto, Lombardy, Trentino-South Tyrol, Piedmont, and Liguria. Piedmont’s membership in the Philadelphian union is all the more remarkable given its role in forming Italy as a nation-state.

The Baltic states and many parts of Poland applied for membership, but the Baltic states could not, in the end, give up their Westphalian sovereignty, and the Polish voivodeships, too small to be admitted on their own, could not come up with a suitable agreement for merging and forming new “states” to join the Philadelphian union.

The United Arab Emirates joined as is.

Three of the wealthiest Indian states joined the federation: Karnataka, Tamil Nadu, and Maharashtra. India was upset, but it’s long history of democratic and federal government, along with its close relationship with the West and relative military weakness compared to the union, prevented a war over the three states leaving for the compound republic.

War did not come to China, either, when the federation of free states poached five southern provinces and two special administrative units: Zhejiang, Jiangxi, Fujian, Guangxi, and Guangdong (which merged with Macau and Hong Kong). The provinces were in almost open rebellion against the CCP. They had grown tired of the Party’s paranoia and broken promises. Street protests were massive. There is a history of violent uprisings in the region. The CCP, which had turned inward when Taiwan joined the Philadelphian union in 2025, had impoverished the country. Beijing had a massive military but it was outdated, ill-disciplined, and corrupt. China had no means to fight a war over the wealthy provinces that joined the compound republic. Unlike the 19th century, when China was humiliated by the West, only the Communist Party of China was humiliated in this confrontation.

Six of Brazil’s wealthiest states also joined the Philadelphian interstate order: Rio de Janeiro, Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Paraná, Santa Catarina, and Rio Grande do Sul. Atlas shrugged, and the compound republic responded.

Lebanon gave up its sovereignty, too, but it joined Canaan so no new Senators were added. (I didn’t do the math, but Canaan might or might not get another seat in the House of Representatives.)

Secessionist movements have flowered since the experiment in self-government under the Madisonian constitutional order went global. It’s a counter-intuitive notion: the larger the Philadelphian union gets, the more secessionist movements flourish. In 2055, there were 26 more “states” that joined the compound republic, giving the union 127 members overall.