- Pontius Pilate: the first Christian? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Politics and forgiveness – a leftist proposal John Holbo, Crooked Timber

- Bumps on the road to pot legalization Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- America’s bewildering imperialism Damon Linker, the Week

Bad guys and bad thinking

AOC made waves with her recent “lightning round” during a hearing on a new campaign finance behemoth lumbering through the House, HR 1. Her basic point was that under our current campaign finance regime, it’s “super legal” to be a “pretty bad guy.”

I wrote recently that much campaign finance rhetoric resembles a religious canon. If so, then AOC is vying for the position of high priestess. I can’t review all the many flaws in her five-minute fable, but I’ll briefly canvas her commitment to orthodoxy.

First, she asks the hearing panel whether there is anything stopping a “bad guy” from being entirely funded by corporate PACs. The panel answered that no law prevents that. But surely common sense does. Running on a campaign solely funded by corporate PACs would be a titanically stupid campaign strategy. First off, thanks to disclosure laws and the realities of a media-rich society, all constituents would know that the candidate was running solely off corporate PACs. Why any candidate would intentionally sell themselves as a corporate lackey is beyond me.

Not only would this look bad, but it would also come at a huge financial cost. Congressional campaigns are mostly funded by individual contributions, not corporate PAC money, so basically a candidate would be refusing a huge amount of loot in order to broadcast themselves as the Peter Pettigrew of electoral candidates. I’m not convinced this is a looming threat to our democracy. Why should we regulate a non-existent problem?

Of course, she also trotted out important theological terms such as “dark money.” She seems to think campaigns are directly funded by dark money. Not so–any contribution over $200 faces extensive disclosure requirements. Dark money usually refers to independent political expenditures, which still face a variety of disclosure requirements and make up a surprisingly small amount of total political expenditures. Again, she is swiping at phantasms.

A larger issue is that even if her claims are true, HR 1 and most other campaign finance laws are hugely overbroad. The overwhelming majority of political spending occurs with no eye toward extracting favors from a candidate. Yet HR 1 would impose huge burdens on all groups speaking in the political arena. The better route to catch “bad guys” is to enforce criminal laws that prohibit bribery. Will you catch every instance of quid pro quo corruption? Almost certainly not. But since when was this a controversial price to pay for a free society? We’ve long ago decided that it’s best to have less than perfect enforcement in order to preserve individual liberty.

The collateral damage that HR 1 would impose on legitimate, non-corrupt speech is tremendous. I’m not confident AOC is fretting over the real “bad guy.”

Nightcap

- The battle for truth in Soviet science Michael Gordin, Aeon

- Governing least: a New England libertarianism Dan Moller, Bleeding Heart Libertarians

- A tale of two paths Michael Koplow, Ottomans and Zionists

- 10 walls that have actually been built – My latest at RealClearHistory

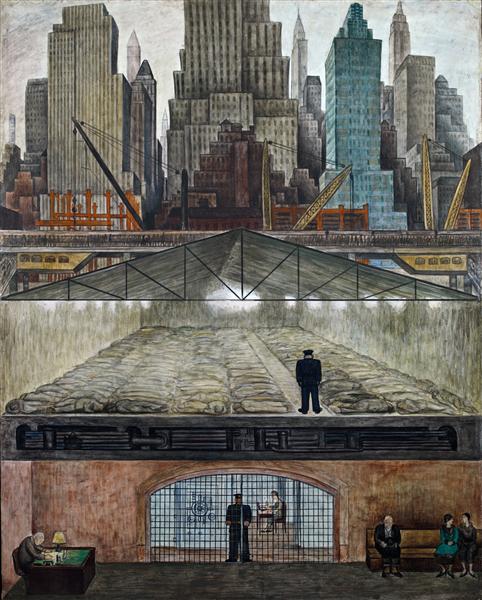

Afternoon Tea: Frozen Assets (1931)

This is from the communist Mexican artist Diego Rivera:

Created during the Great Depression, this one is almost too predictable. It’s beauty alone, though, makes it worthy of an afternoon with tea.

Nightcap

- In defence of prejudice Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- Escaping our Ship of Fools Mark Pulliam, Law & Liberty

- Against libertarian populism Zak Woodman, NOL

- How the Left continues to destroy itself Conor Friedersdorf, the Atlantic

Liberty and pro-choice arguments

Abortion never struck me as a liberty issue. Fundamental ideas that inform libertarian thinking don’t pick a “side” for or against abortion, late-term or otherwise. Abortion is a random issue. But my pro-choice credentials face greater and greater scrutiny as I pal around right-libertarians and conservatives, and I’ve had to re-investigate my own decision-making process here.

I find each political side — abortion jurisprudence — wholly unconvincing. When a sperm and egg becomes “life” is so outside thousands of colloquial years of the word, there’s nothing analytic in the definition to illuminate policy choices; I don’t think medical science is going to answer the philosophical question of the concept of “life” either (“clinical death” violates what should be commonsense notions of death); etcetera. And then, of course, the pro-choice camp (which emphasizes parental choice) rarely cares about parental choice afterward, like in education, and the pro-life camp is an absurdly broad name for their legitimate concerns. The philosophy of abortion is probably interesting — the politics is a waste of time.

Here is what, I think, enforces my libertarian advocacy of choice. I am probably more radically pro-choice than most people I know, but this provides a basic defense.

If the question of whether or not life is “worth it” is a sensible question in the first place, then it is not one that can be answered a priori. Life is an inherently qualitative experience. This is clear enough by the fact that some people would rather choose to have died at age 60 after having lived to age 80, if we take their judgment as the best authority on their own life’s worth (and I do, and I think we should). Therefore, in advance, its not knowable if a person’s life will be worth it. People generally do enjoy living (more than they would otherwise?); this might not be the case if, for instance, the Nazis won and we all were born in camps. This is an accidental property of the current world. We live in a generally worthwhile time period, suggesting life is generally going to be determined to be worth it by each individual.

Since the worth of life is not a priori, the best guess in advance is that from local knowledge. Parents have the most local knowledge about the future of their child’s immediate life, before it gets unpredictable and the knowledge gets divided by millions of individuals who will impact their life and also understand ongoing trends. Therefore, parents are the best option to make a judgment call about whether or not their child’s life will be worth it — if they can care for it, if they will have a genetic problem, etc. Not politicians. Not voters. Not interest groups concerned with in utero life in the abstract.

Thus, parental choice.

It’s been said this is an “anti-human” argument. Lots of us came from lower income or impoverished households, myself included. Our lives are still found worthwhile. Why strawman, as if we’re in countries with terrible childhood obesity, malnutrition, drug addiction, gang violence?

It’s true that in general life is found to be worthwhile. But there’s no Leibniz-like principle that it must be. Nor does the aggregate data that people do, often, qualify life as worth living, mean that random individuals overcome parental ownership of the best localized knowledge.

This, I think, is a libertarian argument for choice. It depends on the point that abortion is a unique sort of event — we’re not talking about an old man’s caretaker, who must have the best local knowledge about whether or not we should pull the plug. The question need not arise about who makes important choices once someone is cognizant and autonomous. The argument rides on the point that there’s a vacuum in decision-making autonomy for fetuses by their very intrinsic nature, and we have to make proxy choices in advance.

We give parents plenty of other choices by law. When we are debating potential- or possible-beings still in the womb, before our language game definitively identifies them as “alive,” choice should default to the parents, and I should have no right to the woman’s body to make choices for her about a possible-being I will never see, feed, care for or otherwise worry about except to force the woman to take care of it for nearly two decades.

What’s the biggest takeaway from my Blockchain classes?

We are nearing the end of my first semester as a Blockchain lecturer at a local university. We have discussed many topics, such as cryptography, consensus protocols, tokenization, smart contracts, how to build your own crypto-token…

During the final examination, I have asked what their biggest takeaways are from my classes. Do you know what the biggest takeaway is among most students?

It’s that they will never look at government and money the same way again. None of them had heard of the word Libertarian before, but now they leave the classes a little more sceptical of government and hopefully a little more libertarian.

Nightcap

- The world nationalism made Liah Greenfeld, American Affairs

- Remember the Kurds Shikha Dalmia, the Week

- The Kautilyan Prime Minister Kajari Sahai, Pragati

- Being Nigerian in Ghana Titilope Ajayi, Africa is a Country

Nightcap

- How Mao took over the CCP Francis Sempa, Asian Review of Books

- Pentagon walks back Trump idea of using Iraq base to counter Iran Jack Detsch, Al-Monitor

- Hayek against the planners Anne Rathbone Bradley, Modern Age

- The internal contradictions of liberalism and illiberalism Scott Sumner, EconLog

Nightcap

- A visit with Dr Quack (feeling just fine) Liam Taylor, 1843

- Rushdie’s deal with the Devil Kevin Blankinship, Los Angeles Review of Books

- The importance of recognition (Venezuela) Elsy Gonzalez, Duck of Minerva

- Should judges pay attention to Trump’s tweets? Amelia Thomson-DeVeaux, FiveThirtyEight

Afternoon Tea: Tramps. Homeless. (1894)

From the estimable Russian artist Ilya Repin:

If anybody knows where this is displayed today, please let me know either by email or simply in the ‘comments’ section.

Nightcap

- How Eric Hobsbawm remained a lifelong communist Richard Davenport-Hines, Spectator

- Chris Dillow’s favourite economics papers Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- The dark individualism of Watchmen Titus Techera, Law & Liberty

- The miracle we all take for granted Marian Tupy, CapX

RCH: MacArthur’s battles

That’s the subject of my weekend column over at RealClearHistory. There’s not a whole lot of information out there about Douglas MacArthur’s battle history, so it’s gotten a lot of attention. I think most people avoid writing about MacArthur because he’s such a polarizing figure. At any rate, here’s an excerpt:

8. Battle of Chosin Reservoir (Nov.-Dec. 1950). Fought on the Korean Peninsula, take a quick moment to reflect on the rapid, violent change that catapulted the United States from regional hegemon in 1914 to world power less than half a century later. And MacArthur served in the military throughout the whole change. The Battle of Chosin Reservoir decisively ended MacArthur’s plans for reuniting Korea under one banner and established the two-country situation of the Korean Peninsula found today. One hundred and twenty thousand Chinese troops pushed 30,000 American, Korean, and British troops out of what is now North Korea and changed the trajectory of the Korean War once and for all. It also led to MacArthur’s political downfall, as his increasingly public calls to attack China’s coastline (with atomic bombs) angered Washington and eventually led Truman to dismiss MacArthur.

Please, read the rest…

Nightcap

- Olive Oatman Ann Turner, 3 Quarks Daily

- Don’t let the rise of Europe steal world history Peter Frankopan, Aeon

- Africa’s forgotten empires David Olusoga, New Statesman

- Colonialism: Myths and Realities Brandon Christensen, NOL