Year: 2017

SMP: The War on Cash: What Do You Have to Hide?

The war on cash we see starting to take place in recent times has a dangerous component. Besides the technical arguments in favor (and against) the efficiency gains of a cash-less economy, politicians are putting forward the argument that only those who have something to hide would oppose to a cash-less economy.

The problem is that this rhetoric implies that any individual is guilty of something until proven innocent. The presumption of innocence, one of the most basic principles of a free society, is being dangerously inverted.

Some economists, including Harvard’s Ken Rogoff, want to minimize the circulation of cash. Such proposals are usually justified on the grounds that they would (1) reduce criminal activity and tax evasion while also (2) helping central banks execute monetary policy when interest rates are at the zero lower bound. Both arguments have been challenged on this blog (here, here, and here).

A Sex Fiend

Like many others, I find the current collective hysteria about sexual harassment a bit overwhelming. Around November 22nd or 23rd, a woman came on FB proclaiming that she was willing to hurt the completely innocent to combat the scourge of harassment of women. She mentioned it was part of the struggle against the “patriarchy.” She said she was willing to “pay the price,” (meaning hurting any number of innocent men). The exchange that followed demonstrated that she was not acting sarcastic. If I were the dramatic kind of guy, I would say this it the beginning of the end of civilization, also a good argument in favor of a now non-existent patriarchy. (Non-existent in the US. Explanations on request.)

Since the repulsive Harvey Weinstein began disgracing the pages of newspapers daily, I have been trying to inject little shots of rationality into the brouhaha. I know it’s not much but if half of all rational people – especially women – do the same I believe we will have a significantly calming effect. Given the overpowering nature of the media excitement, I don’t have the courage to develop an overall strategy of rationality injections. Instead, I do a little bit of this and a little bit of that according to my mood and according to my availability on a particular day. Sometimes the relevance of my intervention to the current situation may seem only tangential. I assure you it’s worth thinking about it though (if you have time).

My main reaction to all of the horror stories in the media is this: Even if they are all 100% true, these stories tell only part of the larger story; they exist in a vacuum. The relationships (plural) between men and women are complex and often conducted at an infra-conscious level. A new fact for our species as a whole is that they are often enacted between perfect strangers. Not long ago, it practically never happened. People had plenty of occasions to find out about one another before anybody made a move. No more. Here is a true story about all this.

A long time ago, I am at an academic meeting in Chicago. I am still a fairly new academic but not a total novice. American university professors are supposed to be actively engaged in scholarship (“research”). Many actually are. Periodically, college professors in their several disciplines get together at academic meetings to present their research papers to one another – sometimes to a nearly empty room. They listen to one another and sometimes, they argue. It’s well understood though that the main function of this custom is to network rather than to spread knowledge. Normally, your employing university pays your way entirely. Such meetings are one of the fringe benefits of academia.

After delivering my own paper, I head for the coffee shop of the hotel where the meeting is being held. It’s about 3PM and I need a pick-me-up. The place is not crowded but most tables are occupied. I find one next to a table where a youngish woman is sitting alone before what appears to be a formal tea-set. As I sit down, I say “Hello” politely. She answers the same way. That’s the established custom at academic meetings: We are not strangers even if we are. My saluting her does not mean I am trying to pick her up, I know and she knows. She is in her early thirties, a very short, slight and pretty women with dark hair and black eyes.

After I order, I introduce myself as one does in such meetings and I ask what’s her specialty and where she comes from. She is a historian employed by a university about which I know little. I am a sociologist at a big Midwestern university. She has a light foreign accent I can’t place. I have a foreign accent not so hard to place, I guess. She asks me if I am French. She is a Lebanese Christian herself. It turns out her people and the French go way back. Her native language is Arabic but her English is perfect. She starts talking about her research and I about mine. We discover that we have earned our doctoral degrees from the same university, within two years of each other. We guess we never crossed paths because we were both studious and we used different ends of the main library there, in accordance with our respective disciplines.

What follows is a conversation of about one hour that should have been recorded for posterity. It was a model of gracious intellectual interchange between two cultured people who have enough in common to be able to communicate untrammeled, but with enough differences that they may yet be interesting to each other. We had much to discuss beside our scholarship, including the little-explored experience of middle-class immigrants to the US. The whole conversation stayed on the highest plane you can think of, no levity, no small talk, no useless words. This interchange might even have been enough by itself to justify the mind-boggling expense of academic meetings. It may have been the best conversation I had had, and have had in my life.

All the while, my new acquaintance has been drinking tea. With a lull in the conversation, she excuses herself to go to the restroom. When she returns, as she is slipping back into her seat, she looks straight a me and she says,

“I want you to know there is zero chance I will have sex with you.”

If I had not been sitting down, I would fallen backward from being embarrassed for her. I was so amazed, it took me several seconds to reply, “I was just thinking the same.” Immediately, I regret my retort because, with its devious ambiguity, it’s impossibly rude. I do what I can by way of friendly noises, to make up for it. Then, we say goodbye. The academic meeting is coming to an end the next day; we don’t bump into each other again. Two years later, we did meet again. But, that is another story, obviously.

What’s your point, you may ask? I don’t know, you tell me, especially if you are a woman.

Party politics and foreign policy in Brazil’s early history

Early Brazilian foreign policy was criticized for being too Europe-centered. Brazil declared its independence from Portugal in 1822 in a process unique in the Americas: Dom Pedro I, the country’s first head of state and government, was the son of Dom João VI, king of Portugal. This gave Brazil a sense of continuity with the former metropolis – unique in the Americas. Although Dom Pedro I renounced his rights in the Portuguese succession line to become Brazil’s first Emperor, early Brazilian foreign policy was very much a continuation of late Portuguese policy.

Early in the 19th century Portugal became involved in the Napoleonic Wars on the English side. Portugal and England enjoyed then an already long friendship. When Napoleon invaded the Iberian Peninsula, Dom João, then Prince Regent, decided to move the Portuguese imperial capital to Rio de Janeiro, instead of fighting a war he believed he could not win. This move consolidated the Anglo-Portuguese alliance of that time, as Dom João’s policy was backed up by England.

In South America, Dom João first decision was to finish the colonial exclusivism Portugal enjoyed with its colony, opening Brazil’s ports to friendly nations. With most of Europe at war and occupied by French armies, England was basically the only friend Brazil and Portugal had at the time. But his policies meant that Brazil had a move towards liberalism unknown until that moment. The country’s trade with the outside world rose as English products entered the Brazilian market.

When Dom João returned to Europe, Brazilian elites were unwilling to give up the freedom conquered in the previous years; in that case, something not that different from what happened in Spanish America. With Dom Pedro I as Prince Regent in Brazil, the independence movement grew strong until complete secession in 1822.

With that in mind, it’s possible to understand how early Brazilian foreign policy was mostly a continuation of Dom João’s policy: Dom Pedro I’s first task was to get recognition of Brazil’s independence from Portugal. That happened with English support. The United States was the first country to recognize Brazil’s independence, but this was welcomed coldly in Rio de Janeiro.

In response to English help, Dom Pedro I kept and improved the trade benefits England already enjoyed with Brazil. He also occupied Uruguay, a region disputed between Spain and Portugal, leading to a war with Argentina and, despite renouncing his rights to the Portuguese throne, kept close relations with his family in Portugal.

Dom Pedro I’s foreign policy was a reason for growing opposition. He could not win a war against Argentina and his connection to Portugal was a constant reason for accusations of recolonization plans. Topping that was the perception of Brazilian elites that the trade agreements with England were bad for Brazil. For these and other reasons, Dom Pedro I resigned in 1831 and returned to Portugal, leaving the Brazilian throne to his son, Dom Pedro II.

Dom Pedro II was only five years old when he ascended to the throne, and so despite being the head of state, he could not govern the country. The 1830’s were a period of regencies when few important decisions were made in Brazil’s foreign policy. But in another topic, that was a crucial decade in Brazilian history: the political tendencies present in Dom Pedro I’s reign became more formal political parties in the late 1830’s: the Conservative Party, that defended progress inside of order, and the Liberal Party, that defended more radical changes.

Dom Pedro II’s adulthood was anticipated in 1840, and besides a short period of Liberal rule, the conservatives dominated Brazilian politics for most of the 1840’s to the 1870’s. In domestic politics, conservatives wanted to centralize politics and bureaucracy in Rio de Janeiro and leave little autonomy to the provinces. They claimed to be afraid of the extremes of mob rule, despotism, and oligarchy, and therefore defended progress inside of order. This meant conserving much of the Portuguese heritage. It was up to the state to build the nation and to lead a modernization process. Ironically, many important conservative leaders were former adversaries to Dom Pedro I and accused him of despotism. However, once in power, they said the country needed to be saved from excesses of liberty.

The conservatives talked about the 1830’s as a period of dangerous upheaval in Brazil. Indeed, the country faced several regional revolts that could have fragmented the Empire. Anyway, the conservative answer was to secure the integrity through a stronger government. In their understanding, Brazil was simply not ready for a certain level of liberty.

A Radical Take on Science and Religion

An obscure yet still controversial engineer–physicist named Bill Gaede put out a video last year, inspired by Martin Luther, spelling out 95 theses against the current scientific consensus in physics. I’m in no position to evaluate his views on physics, but I find his take on the difference between science and religion fascinating. In this post I’ll try to condense some of his views on that narrow topic. You can watch the whole video here. Fair warning: his presentation style is rather eccentric. I find it quirky and fun, you may feel differently.

***

A description is a list of characteristics and traits. It answers the questions what, where, when, and how many.

An explanation is a discussion of causes, reasons, and mechanisms. It answers the question why.

An opinion is a subjective belief. What counts as “evidence”, “proof”, or “truth” is an opinion.

Science is the systematic attempt at providing explanations. Why do planets orbit stars? Why are some people rich and others poor? Why is there something instead of nothing? All questions that can be answered (to varying degrees) with science.

Note well that the experiments and observations per se are not science. The scientist takes those results for granted: they form his hypothesis—literally, that which is without a thesis or explanation. Technicians and assistants may carry out the observations and experiments. But the actual science is the explanation.

Religion is the systematic attempt at shaping opinions. Religion is not mere faith—the belief in things without evidence. Religion works through persuasion—the use of science and faith to appeal to your subjective beliefs about evidence and proof and truth.

Science is not be about persuading the audience. Good science is about providing consistent, logically sound explanations. An individual may have many religious reasons for their incredulity. But religious skepticism is not the concern of the scientist. The scientist is only concerned about logically valid explanations.

How to fix the journal model?

Disclaimer: I am not (yet!) published in any peer reviewed journals.

A companion recently posed an interesting proposal to improve the academic journal model: have referees publish their reviews after X period of time. I am sympathetic to the idea as I have always found secrecy to be a strange thing in decision making. What’s the point of ‘blind’ reviews anyway? From conversing with those with more experience in the field, it is rarely a ‘double blind’ process but a de facto one way ‘blind’ process. This seems to be the case more so outside the major journals.

My counter is: why not just get rid of journals altogether? Why not just publish via SSRN and similar websites? Journals seem to have maintained their existence in the digital age as a means of quality insurance, but there’s still lots of junk in the top journals. Surely we can come up with better ways than relying on a few referees? Even relying on citation count would be a better measure of a paper’s value I think.

#microblogging

North Korea, the status quo, and a more liberal world

The tension on the Korean Peninsula can be felt throughout the entire Pacific Rim right now. North Korea, a dictatorship with a shaky grasp on its populace, has nuclear weapons and is launching non-nuclear missiles over Japan and threatening South Korea and the United States. To make matters worse, the only state in the region that Pyongyang deems worthy of dialogue, China, refuses to engage in much multilateral work to defuse the situation.

If I were South Korea and China I would have an advanced missile shield system right on the border of North Korea, and if I were Japan I would have an advanced missile shield system spread all along my massive coastline. However, China is engaging in trade sanctions against South Korea for trying to build a missile shield along it’s border with North Korea, ostensibly because such a missile shield would threaten Beijing’s territorial integrity. This is a huge strategic mistake on China’s part. North Korea is ruled by the son of a brutal dictator who is in the midst of remaking the People’s Republic in his image. Pyongyang is launching missiles over wealthy democracies and threatening perceived enemies with nuclear annihilation. China is ignoring all of this, and undertaking policies designed to underwhelm multilateral efforts at containing North Korea because Beijing wants North Korea to serve 3 purposes: 1) a useful buffer state (but read this), 2) a hostile reminder that it considers Taiwan as part of China, and 3) as a good bargaining chip when dealing with the United States in the region.

Given that the United States is not geographically a part of East Asia, and given that Washington figures prominently in not one, not two, but all three major reasons why China refuses to engage robustly in more multilateral actions against such a destructive neighbor, we must ask ourselves: Why is the United States still in South Korea? The answer is that Koreans want them there.

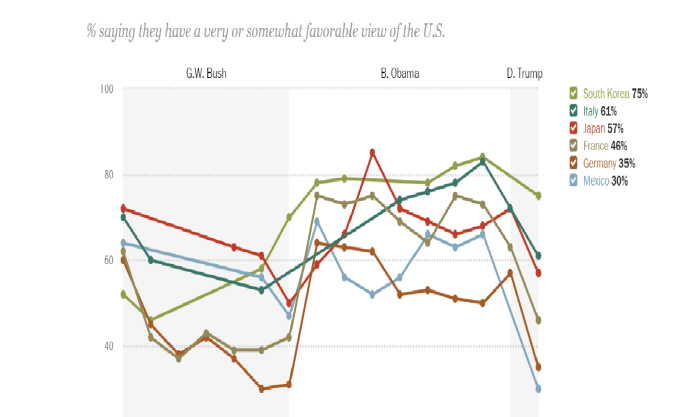

Check out the latest results of a Pew Survey asking people what they think about the United States:

75% of South Koreans have a favorable or somewhat favorable view of the US even after the election of Donald Trump. That’s higher than the other baseball-friendly countries like Italy (61%) and Japan (57%), and much higher than next-door neighbor Mexico (30%) and longtime NATO partner Germany (35%).

China is wrong to believe that an American withdrawal would suddenly make North Korea a breezy member of the international community of states. Kim Jong Un’s regime depends on foreign enemies to survive. James Madison put it best:

The means of defense against foreign danger have been always the instruments of tyranny at home. Among the Romans it was a standing maxim to excite a war whenever a revolt was apprehended. Throughout all Europe, the armies kept up under the pretext of defending have enslaved the people.

North Korea would bully Seoul and Tokyo and cajole Beijing even moreso because Washington would not be there to bear the burden of Liberal Hegemonic Boogieman.

But I’m not a Chinese citizen and this is a post about a more liberal world, so I’d like to switch gears and focus on something that all libertarians are secretly obsessed with: money.

What kind of deal is the US getting by having troops stationed along the 38th parallel? I know the US is a target of a dictator’s nuclear arsenal because of troops along the 38th, and I know the US has to expend considerable resources on the Korean Peninsula to protect Seoul, so costs are understood, but what about benefits? What about payment? What does US get in return for protecting South Korea?

Trade – a big aspect of libertarian foreign policy – is not that big of a deal for either country: the United States makes up about 14% of South Korea’s exports, and South Korea makes up nearly 3% of the United States’ exports. This means that China, for example, is a larger, more important trading partner to both countries than either is to each other.

One of the benefits I’ve found is South Korea’s participation in multilateral military actions undertaken under the umbrella of US military leadership. South Korea has provided troops for dozens of current UN missions in sub-Saharan Africa and post-British Asia, and also participated in the US-led invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq (Seoul’s troops left Iraq in 2008 and Afghanistan in 2014). I also learned that South Korea deployed 325,000 soldiers to South Vietnam from 1964-1973, losing roughly 5,100 soldiers and welcoming home another 11,000 wounded soldiers.

Seoul’s participation in Vietnam was a shocking discovery for me. It forced me to reassess America’s relationship with South Korea. The status quo is actually a decent trade-off. The status quo is cooperative, not coercive. The status quo isn’t so bad from a libertarian standpoint: There is a trade-off with mutually beneficial exchange involved, there is a cooperative rather than coercive relationship between both sides, and tens of millions of people are freer than they otherwise would be because of it.

We can still make the alliance marginally better, though. We can still take small steps to a much better world. Consider federation between the two countries.

On the face of it, such an event is ludicrously radical and completely anathema to liberty and cooperation. I would have had the same reaction just a couple of years ago, but two books have fundamentally changed my mind about this: Daniel Deudney’s Bounding Power: Republican Security Theory from the Polis to the Global Village and David Hendrickson’s Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding. Both scholars are American political scientists and, as far as I can tell, card-carrying Democrats.

Deudney’s book uses theory and history to show that, among other things, republican security theory is, and always has been, from antiquity to the present day, the most important question that scholars of international relations have had to grapple with. For centuries, republics started out with the best of intentions, the best of circumstances, and always managed to decay into despotism or succumb to conquest by neighboring despots. The United States, Deudney goes on, managed to get out of this trap through federal union and, because of its peculiar geographic situation, a full-fledged republican security bargain was able to come to full fruition.

Deudney bases this part of his argument on Hendrickson’s little-known but immensely persuasive book. Hendrickson argues that the newly independent 13 states and their eventual federal union should best be viewed in an international relations framework. In order to protect themselves not only from powerful empires but more importantly from each other, the 13 states entered into a federal union that held them responsible for a limited number of shared responsibilities (such as international security and ensuring republican government in their domestic realms) and left plenty of space for each of them to exercise policymaking as they saw fit. In order to avoid a race to the bottom – where the 13 states formed security blocs between themselves and used Spain, France, and the UK to undermine their rivals – the 13 states built, piece-by-piece, a cooperative international system and called it a federation.

With America’s domestic liberties under increasing assault, largely because the current situation places so much emphasis on certain checks and balances over others, adding additional “states” in the form of South Korea’s provinces would breathe new life into all of the institutions necessary for both security and republican domestic governance.

The inevitable Korean bloc

The biggest fear that such a federation would bring about is the fear of a Korean bloc, or the disintegration of the precarious balance of power between the two parties in the US. Although partisans on both sides no doubt loathe that their side is even with the other in terms of influence and numbers, most Americans are very happy with the two party status quo (if they weren’t happy there would no longer be a two party status quo).

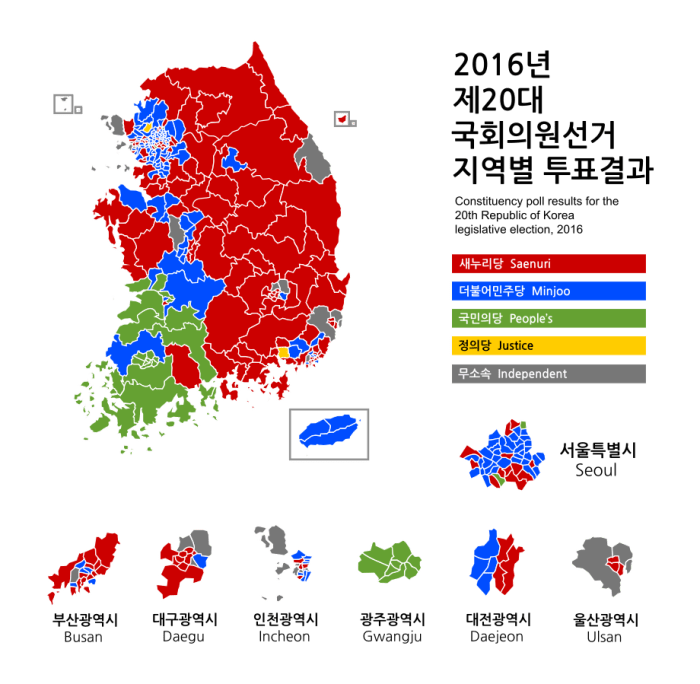

Admitting 5 to 7 new “states,” former Korean provinces, makes it seem like this delicate two party balance would be quickly destroyed with the advent of a Korean bloc which has no interest in traditional American politics. I assure you there would be no Korean bloc. Look at the most recent Korean elections:

There is a Left-Right divide focused on policy and to a lesser extent ideology rather than an ethnic one, just like here in the States.

The Korean Left would line up nicely with Democrats (it even has an anti-American streak that isn’t anti-American at all, only anti-GOP, just like the Democrats!). The conservative wing of South Korea might form a Korean bloc but it would be ineffective in the House and Senate because of its small number.

Libertarians are often dissatisfied with the status quo, even though they’re often the first to point out that life in Western states continues to get better and better. The status quo relationship between South Korea and the United States is great. But it could always be a little bit better.

Is it Thanksgiving without the turkey?

I was recently talking to a friend about Thanksgiving dinner. He was complaining about the difficulty of cooking turkey and asked how my household dealt with the issue. My response? We just serve chicken instead. It’s cheaper, easier to make, and frankly turkey isn’t significantly better.

That begs the question though: can you have Thanksgiving without the turkey? What makes Thanksgiving, Thanksgiving? Being around loved ones is necessary, but not sufficient. We’re, presumably, around loved ones for most holidays. What distinguishes today from other days?

I think it’s the pumpkin pie, but what about my fellow note writers?

#microblogging

More on the trap of college debt

I’m writing this short note to point to John Elliott’s article about how student debt is changing the American family. He has mentored young students at both the Institute for Humane Studies and the Intercollegiate Studies Institute.

The article at times seems to play the idea of going to college against starting a family as two incompatible choices.

Some time ago, though, I wrote a piece on how to avoid student debt, get a degree and even focus on more important things such as work and family.

The article was published here, but as a summary I’m pasting below the “cheap college tips” again:

1. Do well enough at school to get a substantive merit-based scholarship

2. Don’t count on athletics scholarships

3. Start at a community college and transfer

4. Try distance learning at a fraction of the cost

5. Go to a local college and stay with your parents

6. Do your college abroad through distance learning

7. Move abroad and pay much less tuition

8. If abroad, you can still study for a while in America through student exchange

9. Do credit-awarding exams to cut corners – and costs

10. Do French and German for reading (this will save you time and money at Graduate School)

Libertarianism, Classical Liberalism, Right Wing Populism, and Democracy

An interesting exchange has occurred between Will Wilkinson of the Niskanen Center and Ilya Somin writing for the Washington Post on the issue of the influence of libertarianism over the modern Republican Party’s erosion of liberal democratic norms. In his initial piece, Wilkinson seemed to argue that the Libertarian view of absolutism in regards to property rights which was a way to offer an emotionally gratifying alternative to socialist redistribution was responsible for the Right’s adoption of a populist outlook which eroded democratic norms, for example, policies like Voter ID and Gerrymandering. Ilya Somin responded by pointing out that the libertarian “absolutist” conception of property rights had next to nothing to do with why many libertarians Wilkinson cites are skeptical of democracy. Wilkinson responded by saying his initial argument was confusingly stated, not that absolutist property rights is driving democratic erosion on the part of the right, by trying to clarify his distinction between “libertarian” and “classical liberal.” Somin pointed out that this response undermines the force of Wilkinson’s initial argument and took issue with some of his other points.

I wish to contribute to this debate because, even though Somin is largely right that Wilkinson’s argument is weakened by his clarification, I think both have missed that Wilkinson has fundamentally misunderstood what right-wing populism is and why it is a threat to democracy. Modern right-wing populism does not try to erode majoritarian democracy, even if it erodes some of the institutional norms which make it possible for modern liberal democracy to function. Rather, populism, in its many forms, weaponizes democratic rhetoric which is premised on the very notions which libertarians and classical liberals critical of democracy seek to challenge. Attempts to tie such criticisms to the modern right is absurd and distracts us from confronting those aspects which are actually threatening about the right’s pathologies. Afterwards, I will comment on some of the other minor confusions into which I believe Wilkinson falls.

Populism and Folk Democratic Intuitions

In Wilkinson’s genealogy, the root of modern libertarianism is an attempt to weaponize classical liberalism’s defense of property against the desire for socialist redistribution. As he tells it, classical liberals like Hayek and Buchanan sought to put trigger locks on democracy in the form of constitutional constraints on majority rule whereas radical libertarians like Rand, Nozick, and Rothbard sought to disarm democracy altogether from violating property rights. This conception leaves no room for any analysis of or support for democratic decision-making. Since the end of the Cold War, the right has continued to believe this absolutist property rights argument was extremely important even after the Red Menace had been slain and so is willing to do anything, including throwing democracy under the bus, to defend property rights. As Wilkinson puts it:

And that’s why ideological free-market conservatives tend to be so accommodating to, if not exactly comfortable with, populist white identity politics. In their minds, mundane left-right differences about tax rates and the generosity of the welfare state are recast as a Manichean clash between the light of free enterprise and the darkness of socialist expropriation. This, in turn, has made it seem morally okay, maybe even urgently necessary, to do whatever it takes—bunking down with racists, aggressively redistricting, inventing paper-thin pretexts for voting rules that disproportionately hurt Democrats, whatever—to prevent majorities from voting themselves a bigger slice of the pie.

In his follow up, after Somin pointed out that irrational factors like partisanship are more likely to influence a voter’s decision than complicated moral theories such as property rights, Wilkinson attempted to make this argument more plausible by giving the hypothetical example of a white working-class republican voter who, while not fully libertarian, uses his thin knowledge of libertarian property rights absolutism as a form of motivated reasoning justifying his erosion of democratic norms:

Burt is a moderately politically engaged mechanical engineer with ordinary civics-class ideas about democracy, as well as a strong distaste for paying his taxes. (He wants to buy a boat.) One day Burt picks up Atlas Shrugged on the recommendation of a friend, likes it a lot, and spends a few weeks poking around libertarian precincts of the Internet, where he encounters a number of libertarian arguments, like Rand’s, that say that taxation violates a basic, morally inviolable right. Burt happens to find these arguments extremely convincing, especially if he’s been idly shopping for boats online. Moreover, these arguments strongly suggest to Burt that democracy is a dangerous institution by which parasitic slackers steal things from hyper-competent hard workers, like Burt.

Now, none of this leads Burt to think of himself as a “libertarian.” He thinks of himself as a Lutheran, a moderate Republican, and a very serious Whovian. He’s suspicious of “free trade.” He’s “tough on crime.” Burt would never disrespect “our troops” by opposing a war, and he thinks legalizing drugs is bananas. Make no mistake: Burt is not a libertarian. But selective, motivated exposure to a small handful of libertarian arguments has left Burt even more indignant about taxes, and a bit sour on democracy—an altogether new attitude that makes him feel naughtily iconoclastic and a wee bit brave. Over time, the details of these arguments have faded for Burt, but the sentiments around taxation, redistribution, and democracy have stuck.

Ayn Rand and the other libertarian thinkers Burt encountered in his brief flush of post-Atlas Shrugged enthusiasm wanted him to be indignant about redistribution and wanted him to be sour on democracy. He drew the inferences their arguments were designed to elicit. The fact that he’s positively hostile to other elements of the libertarian package can’t mean he hasn’t been influenced by libertarian ideas.

Let’s suppose that, a few years later, a voter-ID ballot initiative comes up in Burt’s state. The local news tells Burt that this will likely make it harder for Democrats to win by keeping poorer people without IDs away from the polls. Burt rightly surmises that these folks are likely to vote, if they can, to take even more of his money in taxes. A policy that would make it less likely for those people to cast a ballot sounds great to Burt. Then it occurs to him, with a mild pang of Christian guilt, that this is a pretty selfish attitude. But then Burt remembers those very convincing arguments about the wickedness of democratic redistribution, and it makes him feel better about supporting the voter-ID requirement. Besides, he gives at church. So he votes for the initiative come election day.

That’s influence. And it’s not trifling, if there are a lot of Burts. I think there are a lot of Burts. Even if the partisan desire to stick it to Democrats is doing most of the work in driving Burt’s policy preference, the bit of lightly-held libertarian property rights absolutism that got into Burt’s system can still be decisive. If it gives him moral permission to act on partisan or racial or pecuniary motives that he might otherwise suppress, the influence might not be so small.

The problem here is not just, as Somin says, that this dances around the issue that people like Burt have become less libertarian over time and so it seems silly to blame libertarianism for his actions. It sounds as if Wilkinson has never actually talked to a populist-leaning voter like Burt. If you do, you will not find that Burt is skeptical of democracy or sees himself as defending some important ideal of laissez-faire capitalism against irrational socialist voters who are using democracy to destroy it. It is more likely that you will find that Burt sees himself as defending the “silent majority” who democracy should rightly represent from evil liberal, socialist and “cultural Marxist” elites who are undermining democracy, and how Trump will stop all the elitist liberals in the courts and media from alienating the common man with common sense by “draining the swamp.”

Read, for example, Rothbard’s original call for libertarians to ally with nationalist right-wing populists. In it, you’ll find no mention of how small “d” democracy attacks property rights because voters are rationally ignorant, and you won’t find, to quote Wilkinson, skepticism towards “a perspective that bestows dignity upon democracy and the common citizen’s democratic role.” Instead, you’ll find that the “grassroots” of the right-wing common man like the secessionists and neo-confederates who are defending property rights against the “socialist tyranny” of the “beltway elites,” Clintons, and the Federal Reserve. Modern adherents to this Rothbardian populist strategy define populism as “a political strategy that aims to mobilize a largely alienated base of the populace against out-of-control elites.” It sounds more like a radically majoritarian, Jacksonian screed about how the voice of the people needs to be truly represented.

Importantly, what the libertarian populists are trying to do is take the folk democratic intuitions which populist right-wingers have, intuitions upon which most peoples’ beliefs in the legitimacy of democracy rely, and channel those intuitions in a more thinly “libertarian” direction. Unfortunately, this is why many modern right-libertarians in the style of Ron Paul are impotent against white supremacists and often try to cozy up to them: because an important part of their strategy is to regurgitate the vulgar democratic rhetoric in which populists believe.

By contrast, modern skeptics of democracy in libertarian circles (or “classical liberal” or “cultural libertarian,” whichever semantic game Wilkinson wants to play to make his argument coherent), such as Ilya Somin, Bryan Caplan, and Jason Brennan, fundamentally undermine those folk democratic intuitions. While right-wing populists believe that the “common man” with his “common sense” knows better how the world works than the evil conniving academic elite does, the libertarian skeptic of democracy points out that the majority of voters know next to nothing and fail to be competent voters due to their rational ignorance. While populist voters believe that the voice of the majority should rule our governing structure, public choice tells us that “majority will” is mostly an illusionary concept. While populist voters believe that the “trigger locks” like courts are evil impediments to the people’s will and regularly attack them, libertarian skeptics of democracy view such institutions as the last line of defense against the irrational and ignorant mob of hooligan voters.

In fact, if people listened to folks like Somin and Brennan, populism of the sort that we’ve seen on the right would be an impossible position to maintain. This is partially why Rothbard largely rejected the public-choice analysis on which scholarship like Somin’s depends.

To try to link modern public choice-inspired skepticism of democracy with populism of any form, even in its most pseudo-libertarian form of the late Rothbard, is to grossly misunderstand populism, classical liberalism, and libertarianism. It seems rather odd to blame Somin and company for the rise of a political ideology which their arguments render incoherent. A Nancy MacLean-like conspiracy to undermine majority rule doesn’t have much of anything to do with the modern right when they think they are the majority who’s being oppressed by elites.

Neither is this some trivial matter of simply assigning blame incorrectly. The problem with populism on the right which has eroded American democracy is not that it thinks democracy is wrong, most populists naively have a lot of folk intuitions which imply some sort of vague proceduralist justification of strongly majority rule. Rather, they’ve taken the majoritarian, quasi-Jacksonian rhetoric (rhetoric to which libertarians other than Rothbard and classical liberals alike have mostly been opposed) which democrats often use and weaponized it in a manner that undermines the non-majoritarian norms on which liberal democracy is dependent for functioning. For someone like Wilkinson, who defends liberal democracy vigorously, misunderstanding the very nature of the threat seems like a particularly grave error as it renders his arguments impotent against it.

Democratic Majoritarianism versus Democratic Norms

In part, I think Wilkinson falls for this trap because he makes a conceptual confusion between the non-majoritarian liberal ideals on which democracy depends—towards which most libertarians are sympathetic—and democracy’s institutional form as majority rule. I’ve described this as a distinction between “institutional democracy” and “philosophical democracy” in the past, and have argued that one can uphold philosophical democratic norms while being skeptical of the current institutions in which they are embedded. Wilkinson argues, citing an article by Samuel Freeman, that libertarian absolutist conception of property is inherently illiberal as it implies a sort of propertarian, feudalist order. Of course, Wilkinson neglects to mention a response to Freeman by Peter Boettke and Rosolino Candela claiming that Freeman misunderstands the role property rights play in libertarian theory.

I am not an absolutist natural property rights-oriented libertarian at all, however in their defense, it is wrong for Wilkinson to think that belief in absolutist property rights—even to the point that one becomes an anarchist like Rothbard—means one is necessarily willing to do anything to undermine democracy to defend property rights. As Somin mentions, not all libertarian absolutists in property completely disbelieved in government like Nozick, but more importantly one can be an anarchist who is strongly skeptical of democracy for largely propertarian reasons but still believes, given that we have democracy, certain norms need to be upheld.

Norms such as equality before the law, equal footing in public elections (which Gerrymandering violates), and equal access to political power (which Voter ID laws violate). Just because one believes neo-Lockean arguments about property rights are valid does not mean one cannot coherently also endorse broadly Hayekian accounts of non-majoritarian liberal norms which make it possible for democracies to function (what Wilkinson calls “trigger locks”), even if in particular instances it might result in some property rights violations.

In other words, one can be skeptical that institutional democracy is moral for libertarian reasons while still embracing a broadly philosophically democratic outlook, or simply believe it is preferable to keep some democratic norms intact given that we have a democracy as an nth best possible solution.

What Wilkinson takes issue with is how the modern right attacks the sort of norms which make democracy work, norms with which no libertarian ought to take issue with given that we have a democracy as they are precisely the “trigger locks” which Hayek called for (even if libertarians want much stronger trigger locks to the point of effectively disarming governments). To think these norms are identical with how many libertarians think the specific voting mechanisms which democracy features are flawed is a conceptual confusion.

An Alternative Account of the Relationship between Libertarianism and the Right’s Pathologies

To me, it seems that Wilkinson’s attempt to shoehorn the somewhat nuanced (by the standards of electoral politics, if not by the standards of academic philosophical argumentation) philosophical arguments of Nozick and Rothbard into an account of the rise of Trumpian politics seems fundamentally inconsistent with the way we know voters act. Even if voters sometimes use indirect intellectual influences as a way to reason about their voting preferences in a motivated manner likes Wilkinson imagines, it’s not really explaining why they need to use such motivated reasoning in the first place. Here’s an alternative account:

During the Cold War, as Wilkinson notes, libertarians and conservatives had a common enemy in communism and socialism. As a result, fusionism happened and libertarians and conservatives started cheering for the same political team. After the end of the cold war, fusionism continued and libertarians found it hard to stop cheering for the “red” team for the same tribalist reasons we know non-libertarian irrational voters remain fiercely loyal to their political parties. Today, even though the GOP is becoming extremely less libertarian, some libertarians find it hard to stop cheering for the GOP for the same reasons New England Patriots fans still cheer for Tom Brady after the deflation scandal: old tribalist affiliations are hard to break.

The only real link between libertarians and modern right-wing pathologies are that some voters who have vaguely libertarian ideas still cheer for populist right-wingers in the GOP because they’re irrational hooligans who hate the left for tribalist reasons. This accords better with the fact voters aren’t all that ideological, that they (unlike Burt who’s interested in just lowering his own taxes selfishly) vote based off of perceived national interest more than self-interest, and how we know generally voters behave in partisan tribalist patterns. But this doesn’t make libertarianism any more culpable for the rise of the modern right’s erosion of democratic norms any more than (and probably less than given its limited influence) any other ideological current which has swayed the right to any degree.

How does this make sense of Wilkinson’s only real, non-hypothetical evidence of libertarian influence on the modern GOP, that some right wing politicians like Paul Ryan and Rand Paul sometimes cite Ayn Rand and Rothbard? Politicians sometimes use intellectual influences haphazardly to engage in certain sorts of motivated-reasoning to cater to subsets of voters, even though they overwhelmingly disagree with those thinkers. This why Paul Ryan first praised Ayn Rand, to get some voters who like Rand, and then later emphasized how much he rejected Rand. This is why Rand Paul cites libertarians simply to virtue-signal to some subset of libertarianish voters while constantly supporting extremely un-libertarian policies. Ted Cruz has said that conservatives “should talk about policy with a Rawlsian lens,” but nobody thinks that Rawls has been particularly influential over Cruz’s policy decisions. All politicians do when they cite an intellectual influence is try to play to cater to the tribalist, pseudo-intellectual inklings of some nerdy voters (“I read the same guys as you do, therefore I’m on your team”), it usually doesn’t mean they really were deeply influenced by or even understand the thinker they cite.

Libertarians and Classical Liberals

Let me conclude this article by addressing a side-issue of how to parse out the distinction between classical liberals and libertarians. One of Wilkinson’s ways of clarifying his disagreement with Somin was by claiming that there is something fundamentally different between “libertarianism” and “classical liberalism.” As Wilkinson puts it:

Absolutist rights-based libertarianism isn’t really part of this conversation at all. It’s effectively an argument against liberalism and the legitimacy of liberal political institutions, which is why it’s so confusing that the folk taxonomy lumps libertarianism and classical liberalism together, and sets them against standard left-liberalism. The dispute between liberalism and hardcore libertarianism concerns whether it’s possible to justify democratic political authority at all. The dispute within liberalism, about the status of economic rights and the legitimate scope of democratic decision-making, is much smaller than that.

Thus, Wilkinson seems to think that libertarians think political authority can’t be justified given that property rights are absolute and that classical liberals just think economic liberties should be included as liberal liberties. However, in my view this taxonomy of ideologies is still confused. Many who typically count as “libertarians” do not fit neatly into such a schema and need to be ignored.

You need to ignore significant portions of libertarians who still endorse property rights but think they are insufficient to a full conception of liberty and endorse other liberal freedoms, like the aforementioned Peter Boettke paper. You need to ignore intuitionist libertarians who do not endorse an absolutist conception of property rights but still dispute that political authority is justified at all, like Mike Huemer. You need to ignore consequentialists who do not embrace absolutist property rights as a philosophical position but think some sort of absolutist property-based anarchist society is desirable against liberal democracy, like David Friedman and Don Lavoie’s students. You need to ignore “thick” left libertarians like Charles Johnson and Gary Chartier who endorse libertarian views of rights yet think they imply far more egalitarian leftist positions. Further, you’d need to claim that most people the public readily identifies as some of the most influential libertarians of all time, like Hayek and Milton Friedman, are not actually libertarian which obscures rather than clarifies communication. Basically, the distinction is only useful if you’re trying to narrowly clarify disagreements between someone like JS Mill and someone like Rothbard.

I agree that there are distinctions between “libertarians” and “classical liberals” that can be drawn and the folk taxonomy that treats them creates a lot of confusion. However, it seems obvious if one talks to most libertarians, there is more going on in their ideology than just “property rights are absolute” and that there is a strong intermingled influence between even the most radical of anarchist libertarians and classical liberals. It is also true that there are a small minority of libertarians who are thoroughly illiberal (like Hoppe), but it seems better to just call such odd illiberal aberrations “propertarian” and still treat most libertarians as a particularly radical subset of classical liberals.

Ultimately, however, I think this taxonomical dispute, while interesting, isn’t particularly closely related to the problem at hand: the relationship between right-wing populism and libertarianism.

In Praise of Academia

This week I got the happy news that my article on Ayn Rand’s views on international relations was accepted for publication. Once it is posted ‘online first’, I shall write a bit about its content. For now I would like to make a two other points, though.

One of the reason for my happiness is that this article took an exceptional time to get accepted. I started working on it in 2010, doing the initial reading (in this case all published works of Ayn Rand). The actual drafting started in 2011, I solicited commentary, and came to an acceptable first version in 2013. To be sure: I did not work on the paper on a full time basis, and there were many other distractions, not least my day time job, other academic projects, and family affairs. Still, the article kept nagging in the back of my head, perhaps not daily, but certainly on a weekly basis. I got the first few rejections by journals in 2013, then again a few in 2015, and another one this summer. So reason enough to be happy to get accepted and all the more exciting to see it through the production phase in the coming months, with actual printed publication still in the somewhat distant future.

I am not writing this to congratulate myself in public. My reason for this blog is to show young (aspiring) scholars, that it is completely normal to work on a project for ages, and to get rejected a few times. Yet the reward is sweet. As long as you persevere, are ready to change and edit your text, overcome your anger when you get unjust blind reviews (and believe me: writing on Rand regularly solicits angry, malicious and/or erroneous responses, also from editors and reviewers of high ranked reputed journals), and keep the faith in the possible value of your modest contribution to the world’s knowledge base.

This is a lesson I learned from experience in the past decade or so. But early on, I also greatly benefitted from one of the best and useful guides to PhD research and academic life I have ever come across: LSE professor Patrick Dunleavy’s Authoring a PhD. It realistically describes what to expect of academic life, it’s ups and also it’s downs. So get it, if you are still unsure what to expect of academic life.

The other remark I would like to make is about the unique and open character of academic publishing. It is really great, as a part-time academic, to be able to get published in reputable journals. I am sure the editors of journals and presses are more keen to see academics from highly reputed universities submitting papers and book manuscripts. Yet they first and foremost value content. If you have something interesting to say, and live up to the academic standards, you will get the same chance and treatment as everybody else. That is pretty unique, compared to many other professions.

So: academia be praised!

The Knife is Coming

From yesterday’s (Nov. 11 2017) Wall Street Journal, P. 1:

Top brass at advertising giant Interpublic Group of Cos. told its 20,000 US employees last week they had until year’s end to complete sexual-harassment training. The session quizzes employees on what to do when a co-worker discusses weekend sexual exploits at work or when a colleague comes on to a colleague’s girlfriend after hours […]

“Women are crucial to our business,” says Mr Roth [CEO]. “We need our environment to be safe for all.”

(All boldings mine.)

Let me put the two statements together for you in a familiar television-like form.

John, Mary, and Peter work together in the same office. One day, they go out together for drinks after work. Jane, John’s girlfriend – who works elsewhere – joins them. Peter flirts with Jane (JANE); he even slip her his cell-phone number. Mary (MARY) feels unsafe.

It’s bat shit crazy. Is there no limit to the absurdities we will listen too peacefully?

If a man can create an unsafe work environment for a female colleague by hitting on another woman employed somewhere else and who welcomes the advances, is there any limit to what constitutes sexual harassment?

How about Mark looks at Jeanne – whom he does not know – at the bus stop, and Mark’s coworker, Jennifer catches his look and feels unsafe?

Will anyone shout: “Absurd”?

Myself, I don’t see just absurdity here. Since the Weinstein explosion less than two months ago (but still no lawsuit to tell us what really happened, if anything), I have begun to discern an attempted mass castration. If there is nothing men can do to stop from being sexual harassers who make women feel unsafe – even indirectly, as in the example above – it’s the fact of being a man itself that is offensive and that needs to be repressed. The knife is coming, ladies and gentlemen!

The most disturbing and the most worrisome aspect of all this mass movement is the lack of backbone demonstrated by many male decision-makers, such as Mr Roth, in this story, who hardly needs the operation, by the way.

Not far behind, is the passivity – so far – of rational women who stand to lose a great deal of peace of mind and other benefits, to the extent that the mass surgical intervention succeeds.

Note that I am not hinting at conspiracy. With the powerful domination of a few newspapers and of fewer TV channels, with the effectiveness of the social media, conventional conspiracies have become obsolete. Throw wet garbage and see if it sticks. If it does not, you and your actions will have been forgotten tomorrow anyway. Some harm done; no price to pay!

What needs to be done? Fight back. Denounce every crazy statement. Affirm rationality. Be ready for a little temporary social exclusion. You will soon find that most people are on your side. They just couldn’t believe what they saw and heard until you gave them a shout-out.

SMP: Separating the Technology of Bitcoin from the Medium of Exchange

At the Sound Money Project I have a comment on the importance of distinguishing between the bitcoin technological innovation and its use as a means of exchange. A solid technological innovation does meant that bitcoin is necessarily properly coded to be a successful monetary experiment.

Bitcoin is back in the spotlight as its price has soared in recent weeks. The most enthusiastic advocates see its potential to become a major private currency. But it is important to remember bitcoin is a dual phenomenon: a technological innovation and a potentially useful medium of exchange. One might recognize the technology as a genuine innovation without accepting its usefulness as a medium of exchange.

A feast of classical liberal thought: Mont Pelerin Society in Stockholm

Last week, Stockholm hosted a special meeting of the Mont Pelerin Society (MPS) on the populist threats to the free society. MPS meetings are held under Chatham House rules, which means I cannot report in any detail about the proceedings. Yet a few impressions can be shared.

I have been a MPS member since 2010, when my nomination was accepted at the end of the general meeting in Sydney. In those days the old rules still applied, which meant you had to attend three meetings before you could be nominated for membership. However, this strict rule led to the erosion of the membership base (the MPS was literally starving out), so the rules to join as a member have been made easier.

My first MPS meeting was in Guatemala City, in 2006. I had participated in the essay contest for young scholars which is always organized in the run-up to the bi-annual General Meetings. As a runner-up I won free entry to the meeting. I happened to be in the south of the USA in the weeks before, doing PhD research at the Mises Institute in Alabama, so could easily make the trip to Central America. Because I lived in Manila during those years, I could also easily attend the 2008 meeting in Tokyo.

I had are number of reasons for wanting to join the MPS. First of all, the quality of the meetings offer a great chance to listen to and speak with the leading scholars within current classical liberalism. Increasingly multidisciplinary (back in the old days the economists dominated), the programme committees of the MPS Meetings always succeed in attracting an impressive crowd of high quality speakers and commentators from across the globe. I always find this a great intellectual treat. Second, the meetings are characterized by extremely pleasant and open atmospheres. Everybody mingles with everybody, you can talk with everybody, no matter your age, or academic background. Thirdly, the meetings take place across the globe, so they offer a great opportunity to travel and see places. Although it must be added that even when you do not stay at the conference hotel, the meetings are never very cheap, so it remains an investment. Fourth, for a Hayekian like myself, it feels very good to be a member of the society founded by the master himself, which had and has such an illustrious membership, ever since its beginnings 70 years ago.

Besides the big one week General Meetings held every two years, there are shorter regional or special meetings in the other years. Last week’s MPS meeting in Stockholm was a special meeting, very well-organized by the Ratio Institute. The theme was discussed from numerous angles, through sessions on Russia’s foreign policy, the economic issue of secular stagnation, or the danger of political Islamism. Two sessions were focused on new classical liberal ideas to counter the threats. At the opening day there was a session for young scholars to present papers. This was of course also a way to attract new talent and interest in the MPS. And at the end of the second day there was something different: beer tasting while listening to Johan Norberg. A rather splendid combination!

The speakers and commentators were high level, including MPS chair Peter Boettke (George Mason), David Schmidtz (Arizona), Deirdre McCloskey (Illinois), John Tomasi (Brown), Leszek Balcerowic (former president of Poland’s Central Bank), Russia specialist Anders Aslund, German thinker Karen Horn, Jacob Levy (McGill), Mark Pennington (Kings College London), Paul Cliteur (Leiden), Amigai Magen (Hoover Institution), and the energetic Ralf Bader (Oxford). A lineup like this guarantees a number of new insights, solid arguments, and general intellectual stimulus. Many answers were provided, yet in true academic fashion, many questions remain.

While well represented in this program, International Relations are normally a minor topic at MPS meetings, and there are not many IR scholars around (nor are sociologists or legal scholars, by the way). Personally I am convinced that the future appeal of classical liberal thought also relies on taking into account world affairs. So there is a need to keep on writing and publishing about it, to expand the basis for thought, also in the MPS. To hear about the concerns and insights of other classical liberals in other disciplines helps my thought process, besides remaining up to speed with current classical liberal issues in general.

So it was a great meeting again, And for all you young scholars out there: if you are interested make sure to regularly check the MPS website (www.montpelerin.org) to see if there are opportunities to participate in one of the upcoming meetings.

Worth a gander

- the Reformation’s controversies are as relevant as ever

- who stole Burma’s royal rubies?

- the Madras Observatory: from Jesuit cooperation to British rule

- “There are few better illustrations of how a whole host of people can manage to understand absolutely nothing, act in an impulsive and idiotic way, and still drastically change the course of history.“

- MacLean’s new book is bad news for the political Left

- fascism explained via 90-year-old sci-fi film (are you using hyphens correctly?)

- bawdry in the bloodstream (Bohemian nonsense)