[Continuing from my last post, noting that feminists have not behaved monolithically toward pornography, and statistics have not provided any justifiable inference from violent pornography to violent crime.]

Most feminists would align, however, in a condemnation of violent pornography, even if they do not attempt to use legal coercion to restrict it. It has been particularly controversial when material becomes first-person, or even playable. And thus pornography, and violent pornography, often makes an intersection with the videogame industry. To name one infamous example, RapeLay, a role-playing game from a company in Yokohama, Japan, allows the player to assault a defenseless mother and her two children. Some critics argued that the videogame breached the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, agreed to by the United Nations.

New York City Council speaker Christine Quinn called RapeLay a “rape simulator.” Commenting on the game and other controversies, an IGN journalist added: “For many, videogames are nothing but simulators. They are literal replications, and, as such, should be cause for the same kind of alarm the real life equivalents would inspire.” Is this the same motive for consumers though – that of, essentially, practice? On the piratebay download link for RapeLay, a top commenter “slask777” writes: “I highly approve of this for two reasons, [sic] the first is that it’s a slap in the face of every prude and alarmist idiot out there and second, it’s a healthy outlet for the rape fantasy, which is more common than most people believe.”

I suspect that much of the appreciation for videogames is due to their simplicity, to be eventually supplemented by mild and mostly innocent addiction. Then – not to put too much faith in slask777’s psychological credentials – I suspect as well that violent videogames serve a “channeling” function, allowing some instinctual energies to exert themselves in a harmless environment and release some psychological tension. Perhaps the “rape fantasy” is not shared by the majority of the populace, but judging by the comments on the torrent site, the audience for this game cannot be confined to stereotypical images of basement N.E.E.Ts. (Studies of the occupations of internet trolls confirm as well the difficulty of pinning down an image for anonymous internet users). There was even an informative, civil discussion of reproductive anatomy on page one of the torrent site. Following this theory of channeling, we might find similar uses for virtual realities: nonreal locations to perform socially unacceptable acts. Locations for people with genuine sexual or sadistic pathologies, to release their desires and blow off steam without harming other people. The entire premise is empathetic.

Of course, throughout history, any activity which has the possibly of harmlessly releasing what could be described as primordial man, the “reptilian” side, the repressed id, or whatnot, has faced violent opposition from culture, religion, criminal law and various romantic-familial-social apparatuses. Here, we can already expect that, fitting into the category of “recreational and individuational,” virtual reality technologies will face a cultural blowback. RapeLay is an extreme example of both violence and sexuality in videogames: the high-profile protest it received could be expected. (Pornography has even been to the Supreme Court a few times (1957, ’64, ’89). In a separate case, Justice Alito, commenting on RapeLay, wrote that it “appears that there is no antisocial theme too base for some in the videogame industry to exploit.”) This moral outrage, however, is not simply content-based, but medium-based, and flows directly from the extant condescension and distrust toward videogames and pornography.

The simple fact that disparate ideological camps agree on, and compatible groups disagree on, the effects and what to do about pornography and videogames could be seen as demonstrative of the issue’s complexity; in fact, this implies that the nature of opinion on this is fundamental and dogmatic. The opinion provides the starting point for selectively filtering research. There are two logical theories concerning these violent media: the desensitization argument, and the cathartic/channeling argument. Puritans and rebels enter the debate with their argumentative powers already assigned, and the evidence becomes less important.

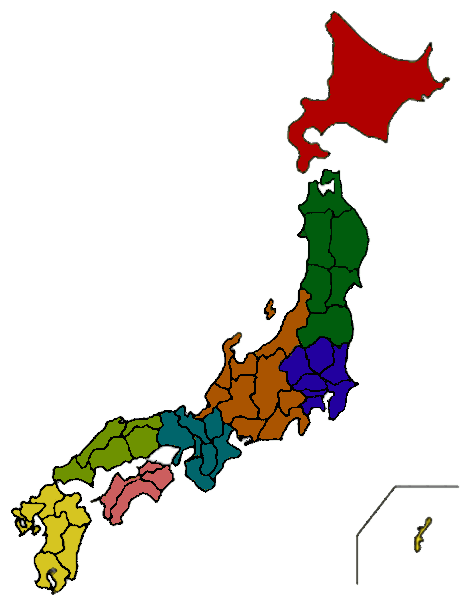

Before evidence that might contradict either primitive position on pornography interferes, many people have already formed their condescension and distrust. The desensitization theory is particularly attractive due on the most publicly-understood thesis of cognitive-behavioral psychology: mental conditioning. Thus when violence or abusive language is used as a male advance in adult videos and games, and women are depicted as acquiescing rather than fighting back, boys must internalize this as reality. Of course, media itself has no interest in depicting legitimate representations of reality; it is inherently irreal, and it would be naïve to expect pornography directors to operate differently. This irreality I think is poorly understood, and thus the “replicator” argument as adopted by the IGN reporter becomes the most common sentiment for people that find pornography affronting to their morals and are also disinterested in research or empirical data. Glenn Beck, commenting on the release of Grand Theft Auto IV, said “there is no distinction between reality and a game anymore.”* He went on to say that promiscuity is at an all-time high, especially with high school students, when the number of sexual partners for young people is at a generational low. The seemingly a priori nature of a negative pornographic effect allows woefully out-of-touch rhetoric to dominate the conversation, appealing also to the emotional repulsion we may experience when considering violent porn. It encourages a simplifying effect to the debate as well. Again, were it simply true that nations with heavy pornography traffic face more frequent sexual violence (as a result of psychological conditioning, etc.), we would expect countries like Japan to be facing an epidemic – especially given the infamous content of Japanese porn (spread across online pornography, role-playing games and manga). Yet, among industrialized nations, Japan has a relatively low rape frequency. The rape ratio of a nation cannot be guessed simply from the size or content of its pornography industry.

Across the board, the verdict is simply still out, as most criminologists, sociologists and psychologists agree. There are innumerable religious and secular institutions committed to proving the evils of pornography, but contrasting them are studies that demonstrate that, alongside the arrival of internet porn, (1) sexual irresponsibility has declined, (2) teen sex has declined (with millennials having less sex than any other group), (3) divorce has declined, and – contrary to all the hysteria, contrary to all the hubbub – (4) violent crime and particularly rape has declined. Even with these statistics, and of course compelling arguments might be made against any and all research projects (one such counterargument is here), violent efforts are made to enforce legal restrictions – that is something that will probably persist indefinitely.

I first became interested in debating pornography with the explosion of “Porn Kills Love” merchandise that became popular half a decade ago. The evidence has never aligned itself with either side; if anything, to this day it points very positively toward a full acquittal. Yet, young and old alike champion the causticity of pornography toward “society,” the family, women, children, and love itself (even as marriage therapists unanimously recommend pornography for marriage problems). Religion has an intrinsic interest in prohibiting pleasurable Earthly activities, but the ostensible puritanism of these opposing opinions is not present in any religiously-identifiable way for a great number of the hooplaers. So an atheistic condemnation of pornography goes unexplained. One might suppose that, lacking the ability to get pleasure (out of disbelief) from a figure-headed faith (which sparks some of the indignation behind New Atheism), people move to destroy others’ opportunities for pleasure out of egalitarianism, and this amounts to similar levels of spiritual zeal. Traces of sexist paternalism are to be found as well, e.g. “it’s immoral to watch a woman sell her body for money,” and through these slogans Willis’ accusation of moral authoritarianism becomes evident. Thus the attitudes which have always striven to tighten the lid on freedom and individual spirituality – puritanism, paternalism, misogyny, envy, etc. – align magnificently with opposing pornography, soft-core or otherwise.

*I try to avoid discussion of GamerGate or anti-GG, but it is almost impossible when discussing videogames and lunatics. Recently, commenting on Deus Ex‘ options for gameplay, which allow the player to make decisions for themselves, Jonathan McIntosh described all games as expressing political statements, and that the option should not even be given to the player to make moral decisions about murder, etc. It’s immoral that there is a choice to kill, was his conclusion. He’s right about all games expressing political statements. But he’s a fucking idiot for his latter statement.

[In my next post I’ll conclude with an investigation into the importance of virtual reality technology and the effect it will have on society.]