- Making Canada great for the first time Scott Sumner, EconLog

- Detoxifying Brexit Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- What’s driving protests around the world? Tyler Cowen, Bloomberg

- “There’s no telling what’s next” Conor Friedersdorf, the Atlantic

immigration

Davies’ “Extreme Economies” – Part 2: Failure

In the previous part of this three-part review, I looked at Davies’ first subsection (“Survival”) where he ventured to some of the most secluded and extreme places of the world – a maximum security prison, a refugee camp, a tsunami disaster – and found thriving markets. Not in that pejorative and predatory way markets are usually denounced by their opponents, but in a cooperative, resilient and fascinating way.

In this second part, subtitled “The Economics of Lost Potential”, Davies brings us on a journey of extreme places where markets did not deliver this desirable escape from exceptionally restrictive circumstances.

There might be many reasons for why Extreme Economies has become a widely read and praised book. Beyond the vivid characters and fascinating environments described by Davies, this swinging between opposing perspectives is certainly one. Whether your priors are to oppose markets or to favour them, there is something here for you. Davies isn’t “judgy” or “preachy” and the story comes off as more balanced because of it.

If the previous section showed how markets flourish and solve problems even under the most strained conditions, this section shows how they don’t.

Darien, Panama

We first venture to the Darien Gap, the 160-kilometre dense rainforest that separates the northern and southern sections of the Pan-American Highway – an otherwise unbroken road from Alaska to the southern tip of Argentina.

To a student of financial history, “Darien” brings up William Paterson’s miserable Company of Scotland scheme in the 1690s; trying to make Scotland great (again?), the scheme raised a large share of scarce Scottish capital and spectacularly squandered it on trying to build a colony halfway around the world. In the first chapter of subsection ‘Failure’, Davies skilfully recounts the Darien Disaster, “Scotland’s greatest economic catastrophe” (p. 114).

Judging from Davies’ ventures into the jungle bordering Panama and Colombia, it wouldn’t be a far cry to call the present state of affairs a similar economic catastrophe. Rather than failed colonies, the failed potential of Darien lies elsewhere: its environmental challenges coupled with the trade and markets that failed to emerge despite readily available mutual gains for trade.

A stunning landscape of mile after mile filled with rainforests and rivers and the occasional lush farmland, the people of the Gap make a living through extracting what the land provides. If you’re deep into environmentalism, you might even say unsustainably so. Davies’ point is to illustrate a more well-known economic problem: when unowned or communally owned resources suffer from the tragedy of the commons – the tendency is for such resources to be overexploited and ultimately destroyed.

Whether through logging companies exceeding their quotas or locals chopping trees out of desperation to survive, the story in Darien is altogether conventional. At the edge of the Gap, “the people of Yaviza do what they can. [T]he environment is an asset, and for many people living in Yaviza getting by is only possible by chipping a bit off a selling it” (p. 120).

What’s striking here is that in times of need (as Davies himself showed in the chapter on Aceh) that’s exactly what we want assets to do! We can show this in down-to-earth, real-world examples like Acehnese women drawing on their jewellery as emergency savings, or in formal economic models such as the C-CAPM, the Consumption Capital Asset Pricing Model, familiar to every business and finance student.

On a much cruder level: if the mere survival of some of the poorest people on earth depend on chopping down precious trees – well, precious to far-away Westerners, anyway – accusing those people of destroying our shared environment is mind-blowingly daft. To rationalise that equation, you have to put a very large value on turtles and trees, and a very small value on human life.

Elinor Ostrom, whose Nobel Prize in economics was awarded to her work on common pool resources, emphasised three ways to solve tragedies of the commons: clear boundaries (i.e. individual property rights); regular communal meetings such that members can voice opinions and amicably resolve conflicts; a stable population so that reputation matters and we can socially police deviant behaviour (p. 125).

The Darien Gap has none of those. Property rights are routinely ignored; the forest includes many different populations (indigenous tribes, farmers, ex-FARC fugitives, illegal immigrants); and those populations fluctuate a lot, meaning that most interactions are one-shot games where reputation becomes useless. End result: extensive, illegal, unsustainable logging mixed with armed strangers.

What I can’t quite wrap my head around is that almost all (market and non-market) interactions that all of us have daily are with strangers: the barista, the people we walk past on the street, the new client you just met or the customer support agent you just talked to. All of them are strangers. A large share of interactions with other humans in the last few centuries of human societies have been one-offs, yet very few of them have spiral into the lawlessness that Davies describes in Darien. Be it the Leviathan, secure property rights, the doux commerce thesis or some wider institutional or cultural reason, but the failure of Darien to establish well-functioning formal and informal markets of the kind we saw in the book’s first part are intriguing.

While a fascinating chapter, it might also be Davies’ worst chapter, factually speaking. He claims, mistakenly, that “globally, deforestation continues apace with 2016 the worst year on record for tree loss”. On the contrary, we’re approaching global zero net deforestation. More specifically, Davies claims that Colombia and Panama are particularly at risk here, with rates deforestation “increased sharply”. A quick look through UN’s Global Forest Resource Assessment report (latest figures from 2015), these two countries are indeed chopping down their forests – but by less than any other time period on record. Moreover, the Colombian net deforestation rate of 0.05% per year is easily exceeded by a number of countries; not even Panama’s dismal 0.3%/year (worse than the Brazilian Amazon) is particularly high in a global or historical perspective.

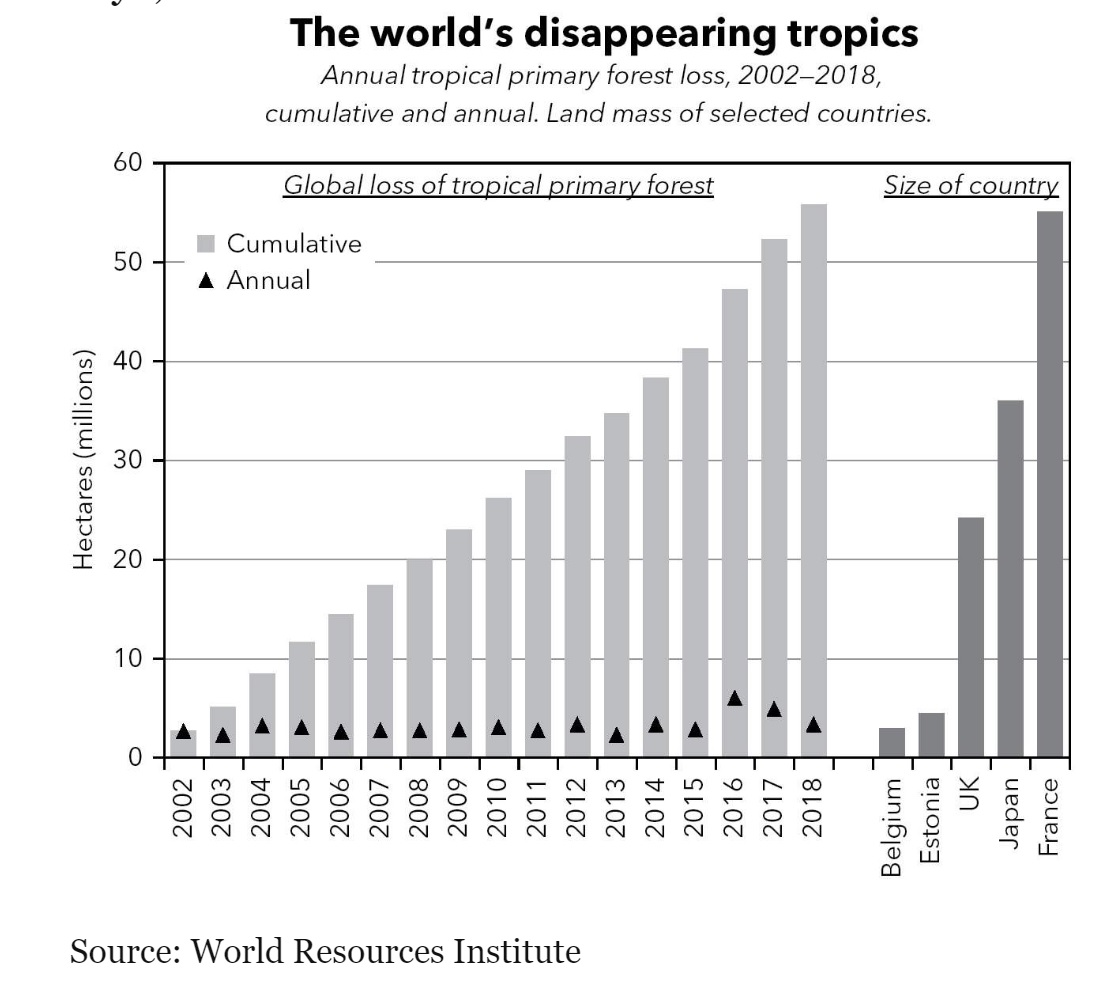

To make matters worse, the figure on p. 158 titled “The World’s Disappearing Tropics” might win an award for the most misleading graph of the year: by making the bars cumulative and downplaying the annual deforestation, it suggests that the forests are rapidly disappearing. The only comparison to relevant numbers (remember, Rosling teaches us to Always Be Comparing Our Numbers) is the tired “football pitches”. That’s hugely misleading. A vast amount of football pitches cleared in the Amazon this year still only amounted to 0.2% of the Brazilian Amazon; in other words, Brazilians could keep chopping down trees for a few good decades without making much of a dent to that vast rainforest.

Moreover, the only reference point we’re given is that over a period of almost twenty years, an area the size of France has been deforested – but that’s equivalent to no more than one-tenth of only the Amazon forest, and the tropics have many more forested areas than that. The graph aims to intimidate us with ever-rising bars signalling the loss of forests; with some proper numbers and further examination it doesn’t seem very bad at all. On the contrary, locals (and yes, international logging companies) use the assets that nature has endowed them with – what’s so wrong with that?

Finally, the “missing market” that Davies observes in the Gap involves countless of illegal immigrants from around the world that trek through the jungles in search of a better life in the U.S. We have cash-rich Indians, willing to pay people to guide them through unknown and dangerous terrain, and local tribes and farmers and ex-FARC members with such knowledge looking for income; setting up a trade between them ought to be elementary.

Instead, it’s not: “in this place of flux,” writes Davies, “reputation does not matter, interactions are one-offs” (p. 137). Overturning the market quip that “trading is cheaper than raiding”, in the Darien Gap raiding is cheaper than trading. One might of course object that the failures of rich countries to offer more liberal immigration rules for people willing to go this far to get there illegally is hardly a market failure – but a failure of government regulation and incompetent bureaucracies.

Kinshasa, Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC)

A 12-million people city sprawled on the banks of the Congo river, so unknown to Westerners that most of us couldn’t place it on a map. Democratic Republic of the Congo, the country with more people in extreme poverty than any other, is frequently described as “rich”. Or, with Davies’ euphemism “unrivalled potential” (p. 143).

Congo, the argument goes, has “diamonds, tin and other rare metals, the world’s second-largest rainforest and a river whose flow is second only to the Amazon. [it] shares a time zone with Paris [and the] population is young and growing”. It is one of the poorest countries but “should be one of the richest” (p. 143).

No, no and no. Before any other consideration of the remarkable day-to-day trading and corruption that Davies’ interview subjects describe, this mistaken idea about wealth must be straightened out. Wealth isn’t what could be if this or that major obstacle wasn’t in the way (Am I secretly a great singer, if I could only overcome the pesky fact that I have a voice unsuited for singing and lack practice?). This is almost tautological; what we mean by a country being poor is that it cannot overcome obstacles to wealth.

All wealth has to be created; humanity’s default position is extreme poverty.

And natural resources do not equate to wealth – there is even more support suggesting the opposite – in which case Japan and Singapore ought to be poor and Venezuela and DRC rich. My own sassy musings are still largely correct:

As Mises taught us half a century ago – and Julian Simon more recently – wealth (or even ‘goods’ or ‘commodities’ or ‘services’) are not the physical existence of those objects somewhere in the ground, but the satisfaction and valuation derived by the human mind. The object itself is only a means to whatever end the actor has in mind. Therefore, a “resource” is not the physical oil in the ground or the tons of iron ore in the Australian outback, but the ability of Human Imagination and Ingenuity to use those for his or her goals. After all, before humans learned to harnish the beautiful power of oil into heat, combustion engines and industrial production, it was nothing but a slimy, goe-y liquid in the ground, annoying our farmers. Nothing about its physical appearance changed over the centuries, but the mental abilities and industrial knowledge of human beings to use it for our purposes did.

Still, “modern Kinshasa is a disaster everyone should know about” (p. 172). No country has done worse in terms of GDP/capita since the 1960s. And we don’t have to go far to figure out at least part of the reason: the first rule of Kinshasa, says one of Davies’ interviewees, is corruption (p. 145). Everyone “steals a little for themselves as the funds pass through their hands, and if you pay in at the bottom of the pyramid there are hundreds of low-level tax officials competing to claim your cash.” (p. 185). Mobutu, the country’s long-time dictator, apparently said “if you want to steal, steal a little in a nice way” (p. 159).

Whether small stallholders at gigantic market or supermarket-owning tycoons, workers or university professors, pop-up sellers or police officers, everyone in Kinshasa uses every opportunity they can to extract a little rent for themselves – out of desperation more than malice. And everyone hates it: “The Kinoise”, writes Davies, “understand that these things should not happen, but recognize that their city’s economy demands a more flexible moral code.” (p. 168).

Interestingly enough, DMC is not a country whose state capacity is insufficient; it’s not a “failed state”, an “absent or passive” government whose cities are filled with “decaying official buildings and unfilled civil-service positions.” (p. 148). On the contrary:

The government thrives, with boulevards lined with the offices of countless ministries thronged by thousands of functionaries at knocking-off time. The Congolese state is active but parasitic, a corruption superstructure that often works directly against the interests of its people.

Poorly-paid police officers set up arbitrary roadblocks and extract bribes. Teachers demand a little something before allowing their pupils to pass. Restaurant owners serve their best food to their civil service regulators, free of charge, to even stay in business. Consequently, despite an incredibly resilient and innovative populace, “these innovative strategies are ultimately economic distortion reflecting time spent inventing ways to avoid tax collectors, rather than driving passengers or selling to customers” (p. 162).

But, like the ingenious monetary system of Louisiana prisons, the most fascinating aspect of Kinshasa’s economy is its use of money. Arbitrage traders head across the river to Brazaville in neighbouring Republic of the Congo equipped with dollars which they swap for CFA – the currency of six central African countries, successfully pegged to the euro. With ‘cefa’ they buy goods at Brazaville prices, goods they bring back over the river and undercut exorbitant Kinshasa prices. Selling in volatile and unstable Congolese francs carries risk, so Kinshasa’s streets are littered with currency traders offering dollars – at bid-ask spreads of less than 2%, comparing favourably with well-established Western currency markets. Before most transactions, Kinoise stop by an exchange trader sitting outside restaurants or malls, to acquire some Congolese francs with which to pay. Almost, almost dollarisation.

In Kinshasa, people rely on illegal trading as a safety net when personal disaster strikes or the state’s required bribes become too extortionary. Davies’ point is a convincing one, that “a town, city or country can get stuck in a rut and stay there” (p. 174).

Judging from his venture into Kinshasa, it’s difficult to blame markets for that. I don’t believe I’m invoking a No True Scotsman fallacies by saying that a market whose participants spent half their time avoiding public officials and the other half bribing them to avoid arbitrarily made-up rules, is pretty far from a free market.

Believing the opposite is also silly – that markets and mutual gains from trade can overcome any obstacles placed before them. Governments, culture or institutions have power to completely eradicate the beneficial outcomes of markets – Kinshasa’s extreme poverty attests to that.

Glasgow, the last part of ‘Failure’, is discussed in a separate post.

The role of religious minorities in combating Islamophobia: The Sikh case

A channel to counter Islamophobia

On the sidelines of the United Nations General Assembly, Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan, Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir Mohammad, and Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan are supposed to have discussed the idea of setting up of a television channel to counter ‘Islamophobia’. In a tweet, the Pakistan PM said that it was decided that the three countries would set up a BBC type channel which will raise Muslim issues and also counter Islamophobia.

The role of Sikh public figures, in the UK and Canada, in countering Islamophobia

It would be pertinent to point out that prominent Sikh public figures in Canada and the UK have played a pivotal role in countering hate towards Muslims. This includes the first turbaned Sikh Member of Parliament (MP) in British Parliament, Tanmanjeet Singh Dhesi (Labour MP from Slough), who criticised British Prime Minister Boris Johnson for highly offensive remarks Johnson had made, in an opinion piece written for The Telegraph in 2018, against Muslim women wearing burqas.

Johnson had stated that Muslim women wearing burqas look like ‘letter boxes and bank robbers’. Dhesi sought an unequivocal apology from the British PM for his remarks.

The Labour MP from Slough stated that if anyone decides to wear religious symbols, it gives no one the right to make ‘derogatory and derisive’ remarks. Dhesi also invoked the experiences of immigrants like himself, and those hailing from other countries, and the racist slurs which they had to contend with.

The leader of the New Democratic Party (NDP) in Canada, Jagmeet Singh, has also repeatedly spoken against ‘Islamophobia’. In 2017, when Singh was still a candidate for the NDP leadership, he was accosted by a heckler, who confused Singh’s religious identity and mistook him for a Muslim. The woman accused Jagmeet Singh of being in favor of imposing the Shariah (Islamic law defined by the Quran) and a supporter of the Muslim Brotherhood.

In a tweet, Singh had then clarified his stance, saying:

Many people have commented that I could have just said I’m not Muslim. In fact many have clarified that I’m actually Sikh. While I’m proud of who I am, I purposely didn’t go down that road because it suggests their hate would be ok if I was Muslim

On September 1, 2019, Jagmeet Singh’s brother, Gurratan Singh, a legislator from Brampton East, was accosted after speaking at a Muslim Fest in Mississauga and accused by Stephen Garvey, leader of the National Citizens Alliance (NCA), of adopting a ‘politically correct approach’ towards issues like ‘Shariah’ and ‘Political Islam’. Gurratan responded calmly, stating that Canada could do without racism. In a tweet later on, Gurratan, like his brother, said that he would never respond to Islamophobia by pointing out that he was not Muslim. Jagmeet Singh also praised his brother for his reaction.

Guru Nanak’s 550th anniversary

That these Sikh politicians in the diaspora are standing up against Islamophobia at a time when Sikhs are preparing to commemorate the 550th birth anniversary of Guru Nanak Sahib, the founder of the Sikh faith, is important. Guru Nanak Sahib was truly a multi-faceted personality – social crusader, traveler, poet, and even ambassador of peace and harmony in South Asia and outside. The first Guru of the Sikhs always stood up for the oppressed, be it against Mughal oppression or social ills prevalent during the time.

Today, Sikhs in the UK, Canada, and the US who have attained success in various spheres are trying to carry forward the message of tolerance, compassion, and standing up for the weak. While being clear about its distinct identity, the Sikh diaspora also realizes the importance of finding common cause with members of other immigrants and minority communities and standing up for their rights. This emphasis on co-existence and interfaith harmony has helped in creating awareness about the faith.

A good example of the growing respect of the Sikh community is not just the number of tributes (including from senior officials in Texas as well as the Federal Government) which have poured in after the brutal murder of a Sikh police officer, Sandeep Singh Dhaliwal, in Houston, Texas (Dhaliwal happened to be the first Sikh in the Harris County Sheriff’s office), but also a recognition of the true values of the Sikh faith, which include compassion, sacrifice, and commitment to duty. While Sikhs still have been victims of numerous hate crimes, in recent years there is an increasing awareness with regard to not just Sikh symbols, but also the philosophical and moral underpinning of this faith.

Conclusion

While countering Islamophobia is important, it can not be done in silos. It is important for minority communities to find common cause and be empathetic to each other’s needs. Setting up a TV channel may be an important symbolic gesture, but it’s overall efficacy is doubtful unless there is a genuine effort towards interfaith globally.

Nightcap

- One summer in America Eliot Weinberger, London Review of Books

- Death in prison, a short list Ken White, the Atlantic

- The tyranny of the economists Robin Kaiser-Schatzlein, New Republic

- Elites and the economy Donald Schneider, National Affairs

Nightcap

- Australia’s shame JM Coetzee, New York Review of Books

- Conservative critics of capitalism Christian Gonzalez, City Journal

- The age of American despair Ross Douthat, New York Times

- The cosmopolitans of Tsarist Russia Donald Rayfield, Literary Review

Nightcap

- What it’s like to be black in Europe Christopher Kissane, Financial Times

- America’s other rebellious border Maxime Dagenais, Age of Revolutions

- Capitalism in America: Up, up, and away Deirdre McCloskey, Claremont Review of Books

- How Italy made me think about America Addison Del Mastro, American Conservative

Nightcap

- Movers and stayers (immigration) John Quiggin, Crooked Timber

- Bryan Caplan steps out of his bubble (and away from libertarian philistinism) EconLog

- Edmund Burke and the idea of national conservatism Yuval Levin, Law & Liberty

- “Never give a cunt a chance to be a cunt.” (Labour’s antisemitism) Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

The 2020 Dems

The two Democratic presidential debates were performed against a broad background of consecrated untruths and the debates gave them new life. Mostly, I don’t use the word “lies” because pseudo-facts eventually become facts in the mind of those who hear them repeated many times. And, to lie, you have to know that what you are saying isn’t true. Also, it seems to me that most of the candidates are more like my B- undergraduates than like A students. They lack the criticality to separate the superficially plausible from the true. Or, they don’t care.

So, it’s hard to tell who really believes the untruths below and who just let’s them pass for a variety of reasons, none of which speaks well of their intellectual integrity. There are also some down-and-out lies that none of the candidates has denounced, even ever so softly. Here is a medley of untruths.

Untruths and lies

I begin with a theme that’s not obviously an untruth, just very questionable. Economic inequality is rising in America or, (alt.) it has reached a new high point. I could easily use official data to demonstrate either. I could also – I am confident – use official figures to show that it’s shrinking or at a new low. Why do we care anyway? There may be good reasons. The Dems should give them. Otherwise, it’s the same old politics of envy. Boring!

Women need equal pay for equal work finally. But it’s been the law of the land for about forty years. Any company that does not obey that particular law is asking for a vast class action suit. Where are the class action suits?

What do you call a “half-truth” that’s only 10% true? Continue reading

Nightcap

- American debt (to immigrants) Gaiutra Bahadur, New Republic

- Why immigrants are superior Jacques Delacroix, NOL

- Misadventures of an anthropologist in Indonesia Tim Hannigan, Asian Review of Books

- Why books don’t work Andy Matuschak

Nightcap

- Making immigration great again John Fonte, Claremont Review of Books

- The post-Brexit paradox of ‘Global Britain’ Sophia Gaston, the Atlantic

- Tyler Cowen interview on mostly geopolitics Assaf Uni, Globes

- The many faces of Muhammad Tom Holland, Spectator

Tariffs and Immigration

Pres. Trump announced yesterday (6/7/19), on returning from Europe, that the threatened tariffs against Mexican imports were suspended “indefinitely.” It looks like Mexico agrees to do several things to stop or slow immigration from Central America aiming at the United States.

Well, I am the kind of guy who, on learning that he has earned the Publishers’ Clearing House Giant Jackpot immediately worries about accountants, and about where to stash the dough. So, here it goes.

Mr Trump never did specify how much Mexico would have to do to keep the threat away durably. Two problems. First, if I were the Mexican government, I would worry about his moving the goalposts at any time.

Second, – and those who hate him won’t miss it – absent specific goals, Mr Trump put himself in a position to claim a (considerable) political victory no matter what happens next. To take an absurd example, if the number of migrants from Central America decreases, by 1% in July and August, he will be able to say, “ I told you so, my tariff pressures work.” As the French say, “ Why cut yourself the switches that will be used to whip you with?”

Part of the agreement reportedly, incredibly, includes a provision that those migrants who are waiting for their American formal court appearance will be allowed to so in Mexico, and be allowed to work there while they wait. This sounds amazingly unfair to Mexico. (I sure hope some significant money changed hands in the background on the account of his provision.) Mexican public opinion is not going to respond well to this feature if it understands it.

Another feature of the agreement is that Mexico will allow itself to be designated as a third and “safe” country. This has to do with ordinary international asylum and refugee agreements language which generally specify that an asylee or refugee may not chose his country of destination but must seek legal status in the first safe country he reaches. So, for Syrians, that would be Greece, or Turkey, rather than say, Germany, or Sweden. You know how well this provision worked out in Europe! Even more seriously, Mexico is not safe by any measure: The Mexican homicide rate is more than five times higher than that of the US – which is itself not low. (Wall Street Journal, 8-9 2019, p. A6). Imagine what it will be against an alien, vulnerable population.

As I write, Mexico is already deploying its National Guard on its southern border to impeach passage. This is a brand new force; it has no experience; expect accidents or worse. When this happens, it won’t play well with the Mexican public. The southern border of Mexico is short, only about 150 miles but still, the Mexican National Guard has only 6,000 members, total.

American conservative opinion remains badly confused about the facts of immigration in general. This, in spite of my own valiant efforts. ( See my “Legal Immigration Into the US” – in 37 short parts, both in Notes on Liberty and on my blog. Ask me for the blog’s name via jdelacroixliberty@gmail.com.) On Friday evening (6/7/19), in less than 30 minutes, I heard two different Fox News commentators refer to the migrants arriving in caravans from Central America and that are overwhelming our national processing capacity as “illegal immigrants.” That’s wrong. People who run after the Border Patrol to turn themselves in as a prelude to their claiming asylum are not illegal immigrants. There is nothing illegal about such acts, however you deplore them. And, in our constitutional tradition, nothing can be deemed retroactively as against the law. If we don’t like what the law currently produces, we must change the law. Period.

I used to hope for a wholesale, inclusive change in our immigration laws. I now think this is not going to happen in a bi-partisan manner because there are still many Dems who deny the obvious: We are currently facing an immigration crisis. If the plight of would-be immigrants held in overcrowded facilities or let loose in strange cities without resources, does not move their hearts, nothing will. I now think the administration should opportunistically seek piecemeal reform as may be facilitated by temporary situations. Big change will not happen until the GOP gains control of both houses of Congress, in addition to the Presidency. I believe that equivalent Dem control would not make immigration reform possible because there are too many liberal ideologues and too many Dem politicians who want open borders, for different reasons.

One more thing: Mainstream conservatives and some spoiled libertarians have been clamoring on the social media that tariffs are wrong, always wrong, wrong, no matter what. They point out rightly that tariffs are first and foremost taxes on the consumers of countries that impose them. I am myself completely persuaded of the merits of free trade as a means to maximize production. This does not prevent me from seeing that trade pressures, including the imposition of tariffs, can be used to extract advantages from other countries. In fact, I suspect such maneuvers may often be the best alternative to military pressure. In this case, and temporarily, I understand, Mr Trump’s tariff mano-a-mano with the tough leftist Mexican president, seems to have borne fruit. So, I would like the never-never–never tariffs people on my side to provide a rough estimate of how much this particular tariff action – against Mexico – may have cost American consumers, total.

Free Immigration is not a Classical Liberal Right

My eye caught this article, which stands in a long tradition among libertarians.

It is the kind of fairy tale theory that gives liberal thought a bad name in general, and classical liberal thought in particular, as it is often confused with libertarianism in the US.

My problem with arguments like these is that they make logical sense, but are practically non-sensical at the same time. I am more than willing to admit that in the ideal libertarian world free immigration indeed is a right. Yet I do not think arguments like these help us to get that libertarian ideal one inch closer. On the contrary, I am afraid it only fosters disdain and outright disbelief, even among potential supporters.

The main problem of course is that there is no ideal libertarian world. Yet libertarians all too often do not seem to care about that. They rather continue to argue about what fairy tales makes the most logical sense, rather than using their sometimes brilliant minds to come up with ideas and theories to actually foster a more liberal world. Let alone a classical liberal or a libertarian world.

To make a case for free immigration on the basis of rights is to deny the property rights of current populations. Roughly, that argument goes like this: in this world most immigrants will make some claim to these existing property rights once they arrive in their host country. Higher taxation to pay for the immigration system is one thing, but also think of housing, claims to health and medical systems, social welfare programs, schools, roads, et cetera. The majority of the current population has put money into (these) public goods, certainly in Europe, and thus property rights were created. These should be protected and can only consensually be changed.

Also, there are more intangible effects, think for example of the change in culture and social cohesion, certainly before the new arrivals are fully integrated. Hayek warned against precisely these destabilizing effects of large groups of immigrants entering a relatively homogenous territory, drawing on his own Viennese experience in the interwar years. He openly supported Margaret Thatcher to this end in a letter to The Times on February 11, 1978, which were followed by further explanations in the same newspaper in the weeks thereafter.

This is not to say we should all build (or rather attempt to build) walls, or close off borders completely. Some form of immigration is indeed called for, if only out of humanitarian perspective. That is something completely different than free immigration though.

Nightcap

- The Mick Mulvaney Presidency Ross Douthat, New York Times

- The Great Disappointment Nick Nielsen, Grand Strategy Annex

- An Addendum to Perpetual Peace Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- “The Other Americans” Michael Carroll, Los Angeles Review of Books

Nightcap

- Economics after neoliberalism (Hayek) Corey Robin, Boston Review

- Should some countries cease to exist? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Consider reparations Robin Hanson, Overcoming Bias

- (Legal) immigration into the United States Jacques Delacroix, NOL

RCH: Calvin Coolidge

I took on Calvin Coolidge this week. My Tuesday column dealt with Coolidge and his use of the radio, while this weekend’s column argues why you should love him:

2. Immigration. At odds with the rest of his anti-racist administration, Coolidge’s immigration policy was his weakest link. Although he was not opposed to immigration personally, and although he used the bully pulpit to speak out in favor of treating immigrants with respect and dignity, Coolidge was a party man, and the GOP was the party of immigration quotas in the 1920s. Reluctantly, and with public reservations, Coolidge signed the Immigration Act of 1924, which significantly limited immigration into the United States up until the mid-1960s, when new legislation overturned the law.

Please, read the rest.