Around early August 2018, a research paper from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University by Charles Blahous made both the Wall Street Journal and Fox News within two days. It also attracted attention widely in other media. Later, I thought I heard sighs of satisfaction from conservative callers on talk show radio whenever the paper came up.

One figure from the study came and stayed at the surface and was quoted correctly many times (rare occurrence) in the electronic media. The cost of what Senator Sanders proposed with respect to national health care was:

30 trillion US dollars over ten years (actually, 32.6 over thirteen years).

This enormous number elicited pleasure among conservatives because it seemed to underscore the folly of Senator Bernie Sanders’ call for universal healthcare. It meant implicitly, federal, single-payer, government-organized health care. It might be achieved simply by enrolling everyone in Medicare. I thought I could hear snickers of relief among my conservative friends because of the seeming absurdity of the gigantic figure. I believe that’s premature. Large numbers aren’t always all they appear to be.

Let’s divide equally the total estimate over ten years. That’s three trillion dollars per year. It’s also a little more than $10,000 per American man, woman, child, and others, etc.

For the first year of the plan, Sanders’ universal health care amounts to 17.5% of GDP per capita. GDP per capita is a poor but not so bad, really, measure of production. It’s also used to express average gross income. (I think that those who criticize this use of GDP per capita don’t have a substitute to propose that normal human beings understand, or wish to understand.) So it’s 17.5% of GDP/capita. The person who is exactly in the middle of the distribution of American income would have to spend 17.5% of her income on health care, income before taxes and such. That’s a lot of money.

Or, is it?

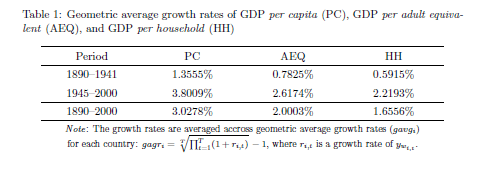

Let’s imagine economic growth (GDP growth) of 3% per years. It’s optimistic but it’s what conservatives like me think is a realistic target for sustained performance. From 1950 to 1990, GDP per capita growth reached or exceeded 3% for almost all years. It greatly exceeded 3% for several years. I am too lazy to do the arithmetic but I would be bet that the mean annual GDP growth for that forty-year period was well above 3%. So, it’s realistic and probably even modest.

At this 3% growth rate, in the tenth year, the US GDP per capita will be $76.600. At that point, federal universal health care will cost – unless it improves and thus becomes more costly – 13% of GDP per capita. This sounds downright reasonable, especially in view of the rapid aging of the American population.

Now, American conservative enemies of nationalized health care are quick to find instances of dysfunctions of such healthcare delivery systems in other countries. The UK system was the original example and as such, it accumulated mistakes. More recently, we have delighted in Canadian citizens crossing the border for an urgent heart operation their nationalized system could not produce for months: Arrive on Friday evening in a pleasant American resort. Have a good but reasonable dinner. Check in Sat morning. Get the new valve on Monday; back to Canada on Wednesday. At work on the next Monday morning!

The subtext is that many Canadians die because of a shortage of that great free health care: It nice if you can get it, we think. Of course, ragging on the Canadians is both fair and endlessly pleasant. Their unfailing smugness in such matters is like a hunting permit for mental cruelty!

In fact, though, my fellow conservatives don’t seem to make much of an effort to find national health systems that actually work. Sweden has one, Denmark has one; I think Finland has one; I suspect Germany has one. Closer to home, for me, at least, France has one. Now, those who read my blogging know that I am not especially pro-French or pro-France. But I can testify to a fair extent that the French National Healthcare works well. I have used it several times across the past fifty years. I have observed it closely on the occasion of my mother’s slow death.

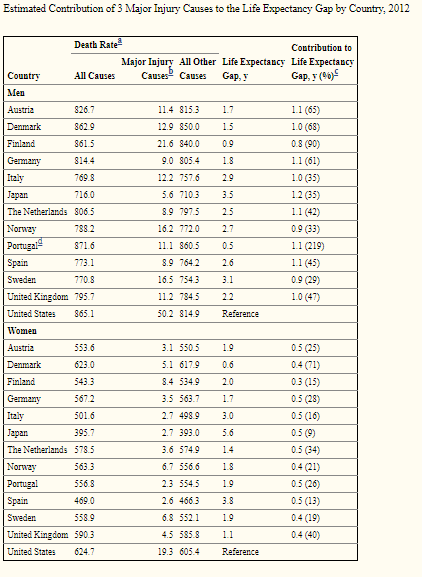

The French national health system is friendly, almost leisurely, and prompt in giving you appointments including to specialists. It tends to be very thorough to the point of excessive generosity, perhaps. Yes, but you get what you pay for, I can hear you thinking – just like a chronically pessimistic liberal would. Well, actually, Frenchmen live at least three years longer on the average than do American men. And French women live even longer. (About the same as Canadians, incidentally.)

Now, the underlying reasoning is a bit tricky here. I am not stating that French people live longer than Americans because the French national healthcare delivery system is so superior. I am telling you that whatever may be wrong with the French system that escaped my attention is not so bad that it prevents the French from enjoying superior longevity. I don’t want to get here into esoteric considerations of the French lifestyle. And, no, I don’t believe it’s the red wine. The link between drinking red wine daily and cardiac good health is in the same category as Sasquatch: I dearly hope it exists but I am pretty sure it does not. So, I just wish to let you know that I am not crediting French health care out of turn.

The weak side of the French system is that it remunerates doctors rather poorly, from what I hear. I doubt French pediatricians earn $222,000 on the average. (Figure for American pediatricians according to the Wall Street Journal 8/17/18.) But I believe in market processes. France the country has zero trouble finding qualified candidates for its medical schools. (I sure hope none of my current doctors, whom I like without exception, will read this. The wrong pill can so easily happen!)

By the way, I almost forgot to tell you. Total French health care expenditure per person is only about half as high as the American. Rule of thumb: Everything is cheaper in the US than in other developed countries, except health care.

And then, closer to home, there is a government health program that covers (incompletely) about 55 million Americans. It’s not really “universal” even for the age group it targets because one must have contributed to benefit. (Same in France, by the way, at least in principle.) It’s universal in the sense that everyone over 65 who has contributed qualifies. It’s not a charity endeavor. Medicare often slips the minds of critical American conservatives, I suspect, I am guessing, because there are few complaints about it.

That’s unlike the case for another federal health program, for example the Veterans’, which is scandal-ridden and badly run. It’s also unlike Medicaid, which has the reputation of being rife with financial abuse. It’s unlike the federally run Indian Health Service that is on the verge of being closed for systemic incompetence.

I suspect Medicare works well because of a large number of watchful beneficiaries who belong to the age group in which people vote a great deal. My wife and I are both on Medicare. We wish it would cover us 100%, although we are both conservatives, of course! Other than that, we have no complaints at all.

Sorry for the seeming betrayal, fellow conservatives! Is this a call for universal federal health care in America? It’s not, for two reasons. First, every country with a good national health system also has an excellent national civil service, France, in particular. I have no confidence, less than ever in 2018, that the US can achieve the level of civil service quality required. (Less in 2018 because of impressive evidence of corruption in the FBI and in the Justice Department, after the Internal Revenue Service).

Secondly, when small government conservatives (a redundancy, I know) attempt to promote their ideas for good government primarily on the basis of practical considerations, they almost always fail. Ours is a political and a moral posture. We must first present our preferences accordingly rather than appeal to practicality. We should not adopt a system of health delivery that will, in ten years, attribute the management of 13% of our national income to the federal government because it’s not infinitely trustworthy. We cannot encourage the creation of a huge category of new federal serfs (especially of well-paid serfs) who are likely forever to constitute a pro-government party. We cannot, however indirectly, give the government most removed from us, a right of life and death without due process.

That simple. Arguing this position looks like heavy lifting, I know, but look at the alternative.

PS I like George Mason University, a high ranking institution of higher learning that gives a rare home to conservative American scholars, and I like its Mercatus Center that keeps producing high-level research that is also practical.