Africa

Large states, artificial borders, and the African exception

Large states have been shown to be correlated with a large number of poor developmental outcomes, including poor institutions (Olsson and Hansson 2009), conflict (Buhaug and Rød 2006; Englebert et al. 2002; Raleigh and Hegre 2009), and ethnic diversity (Green 2010a). Similarly, states with artificial borders have been shown to be correlated with boundary disputes and low GDP per capita (Alesina et al. 2010; Englebert et al. 2002).

Sub-Saharan Africa has been affected by large states and artificial borders perhaps more than any other part of the world. Indeed, while Sub-Saharan Africa and Europe both contain between 48 and 50 sovereign states each, Sub-Saharan Africa is around 2.4 times larger than Europe. Moreover, with 44% of borders drawn as straight lines, “Africa is the region most notorious for arbitrary borders” (Alesina et al. 2010:7). Scholars have thus suggested that Africa’s poor economic development and numerous conflicts have been at least partially a result of its large states and artificial borders (Alesina et al. 2010; Englebert et al. 2002).

However, there is very little scholarship explaining African state size or shape, with previous literature only focusing on the persistence of state size and borders in the post-colonial period rather than on their origins (Englebert 2009; Herbst 2000). Thus my goal here is to probe the origins of state size and shape in Africa.

That’s from this paper (pdf) by Elliot Green, an American political scientist at LSE. Here is Edwin arguing that size doesn’t matter.

Colonialism and Identity in Wasolon (and everywhere else, too)

The notion of the person is constantly renegotiated and is at stake between groups situated within the same political entity as well as between neighboring political entities. With advent of [France’s colonial] district register and the resulting written registration of identity, the notion of a person acquired a greater fixity. It became much more difficult to change identity or even to modify the spelling of one’s first or last name. Since it could no longer affect the components of the person, the negotiation of identity shifted, as in the case of the West, onto other sectors of social and individual life. (135)

This is from the French anthropologist (and high school friend of our own Jacques Delacroix) Jean-Loup Amselle, in his book Mestizo Logics: Anthropology of Identity in Africa and Elsewhere. The book is hard to read. The English translation (the one I’m reading) was published by Stanford University Press in 1998, but the original French language version came out in 1990. Between the translation and the fact that the book was written for specialists in the field of political anthropology and the region of French Sudan, strenuous effort was required on my part to stay focused and motivated to finish the book. The preface alone is worth the price of admission, though, especially if you’ve been following my blogging with any great interest over the years.

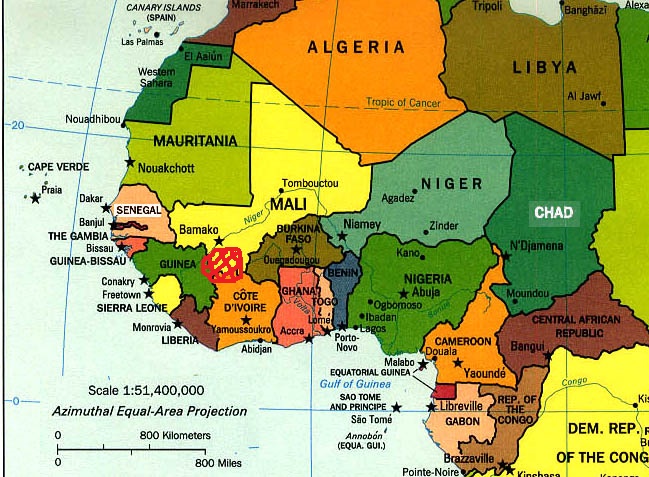

My intent is not to write a review, but rather to build off Amselle’s work and present some of my efforts in blog form here at NOL. But first, a map of the region, Wasolon, that Amselle specializes in:

Wasolon is that big red marking that I’ve drawn on the map. You can see that it’s about as big as Sierra Leone. Just for clarity’s sake, here is a second map with a closer view of Wasolon:

Amselle’s argument for why his approach to identity is superior to others’ is convincing. He performed all of his fieldwork (15 years’ worth as of 1990) in Wasolon, or briefly in neighboring areas, reasoning that “research within numerous regions of a well-circumscribed area […] has allowed me to observe systems of transformation [in] societies that have been in contact for centuries. This has protected me from being forced into large analytical leaps and from engaging in [the current anthropological trends of] abstract comparativism and the identification of structures (xii-xiii).” This defense of his methodology, coupled with his insights on French colonial administration in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, gives me reason to believe that Amselle’s work is an excellent blueprint for better understanding the complete and utter failure of post-colonial states and the violence these collective failures have produced.

I want to take a specific route using the introductory quote, even though I could take a number of different routes using that passage. I could, for example, focus on the invention of the individual and muse about its consequences in regards to the rise of the West. I could go on and on about how other societies had writing – but not the individual- and therefore did not have the institutions necessary for “capitalism” that the West did around the 16th century. Et cetera, et cetera. Instead, I’m going to take a geopolitical route (the West is still practicing colonialism) that has a decidedly philosophical direction to it (nationalism and ethno-nationalism are both bullhooey).

First, the geopolitical context. Wasolon was basically a war zone in the 18th and 19th centuries. It was an important producer of cotton, a minor producer of rubber and ivory, and a net exporter of slaves. Wasolon was unfortunate enough to be caught between Saharan empires backed by Arabic culture, money, and technology, and coastal empires recently enriched through cultural, economic, and technological exchange with rapidly-expanding European populations. Caught between these two geographic poles, polities in Wasolon oscillated between being decentralized chiefdoms, small independent states, empire builders themselves, and vassals of empires. In such an uncertain setting, the identity of people themselves necessarily oscillated as often as their political systems did.

When the French arrived militarily on the scene (there was already a long history of economic, political, and cultural exchange between the “French” and Wasolonians; I put French in quotation marks because, of course, many Europeans found it to be much easier to use “French” as an identity in French Sudan rather than their own), Wasolon was home to many decentralized chiefdoms, and they were all in the midst of a protracted and brutal war with the Samori Empire, a Saharan polity that rose quickly and ruthlessly to prominence in the late 19th century.

The Samori Empire – which the French military was in contact with due to its centralized political structure (it had a bureaucracy and an organized military, for example) – claimed Wasolon as a vassal state and the French, out of ignorance or expediency (to attribute it to malice gives French central planners too much credit), simply took Samori at its word (a policy that continues to play out to this day in international affairs, but more on this below).

The French military commanders and, later, colonial administrators eventually figured out that Wasolon was not a loyal vassal. From the French perspective, the resisting chiefdoms in Wasolon had formed an alliance against the Samori Empire, and this alliance was based on an ethnic solidarity shared by all Fulani. Amselle labors to make the point that this alliance was based on a “mythical charter” long prominent in Fula oral traditions (and has some basis in the historical accounts of Arab and European travelers). This “mythical charter” served as the basis for the French colonial understanding of the Fula and eventually for the notion of a Fulani ethnic identity. The problem here is that the “mythical charter” was just that: a myth.

I’ll start by extracting an insight from the footnotes:

As we saw in Chap. 5, colonial ethnology merely reproduces this local political theory by taking it literally, thereby assimilating these “mythical charters” to a real historical process. Such a reproduction is what makes this ethnology truly colonial. (179)

In the Chapter 5 that Amselle alludes to in his footnotes, Mestizo Logics explains how the Fula people of Wasolon adopted fluid political identities over the centuries, depending on who was in power and who was about to be in power. This fluidity played, and continues to play, a much more important role in how people identified themselves politically (“local political theory”) than either culture or language.

Amselle illustrates this point best by pointing out that a number of chiefdoms in Wasolon claimed to be Fula at the time of the French conquests in the late 19th century, but that the populations spoke a different language than the Fula and were culturally distinct from the Fula (these Wasolon chiefdoms claiming Fulaniship were Banmana and Maninka in language and culture rather than Fula). Amselle then points out that Fula chiefdoms existed outside of Wasolon that don’t claim to be Fula – even though they are culturally and linguistically Fula – and instead identified as something more politically expedient (he doesn’t elaborate on what those non-Fula Fulani identify as, only that they did, and still do).

The French state’s act of writing down and categorizing this “mythical charter” as a distinct feature of Wasolon’s Fulani thus created the Fula ethnic group and, through imperial governance, ensconced this new group into its empire’s hierarchy based on traits that ethnographers, colonial administrators, historians, and managers of state-run corporations had recorded (accounts written by merchants not connected to the state in some way could not be trusted, of course).

Basically, when the French showed up to build their empire in west Africa they bought the narrative espoused by a couple of the factions in the region and based their empire (which was only feasible with the advent of peace in Europe after the Napoleonic Wars) on that narrative. The results of this policy are eye-opening. Aside from the fact that the present-day states of Mali, Cote d’Ivoire, and Guinea are failures, the old rules of fluid identity used by Wasolonians for political and economic reasons were erased and new rules, based on bureaucratic logic (“ethnicity”), were wrested into place by the French imperial apparatus. These new ethnic identities soon took on characteristics, ascribed to them by others, that quickly became stereotypes. The ethnic groups with good stereotypes (like being hard-working) ended up – you guessed it – in positions of power, first in France’s imperial apparatus and then for a short time after independence.

Sound familiar?

If it doesn’t, think about international governing institutions (IGOs) like the United Nations or the World Bank for a moment. Why don’t these institutions recognize the likes of Kurdistan, Baluchistan, or South Ossetia? Is it because these IGOs are evil and oppressive, or simply because these bureaucracies cannot adapt quickly enough to a world where identity and the necessities of political economies are always in flux?

This phenomenon is not limited to post-colonial Africa, either. Think about African-Americans here in the United States and the stereotypes attributed to them. Those stereotypes – good and bad – are a direct result of bureaucracy.

Individualism, to me, is the best way to tackle the long-standing problem created by colonial logic abroad, and racism at home. Government programs that seek to help groups by taking from one and giving to another are just an extension of the bureaucratic logic revealed by Amselle’s work in French West Africa. But what is a good way to go about implementing a more individualized world? Open borders? Federation?

BC’s weekend reads

- Introducing… Jesus and Mo

- On private property and the commons

- Why Merkel’s Kindness to Asylum Seekers Could Reflect a German Soft Spot for Islam

- Why I find the Mthwakazi monarchy restoration unjustified

- September (a song about me)

- From the Far Right to the Far Left

- Beyond Neoliberalism (book review)

From the Comments: The four broad pillars of the market-based economy

NEO’s response to my musings on decentralization in Africa is worth highlighting:

It strikes me , Brandon, that one of the impediments here, there may be others, I’m no expert, is that the nascent US was composed mostly of literate folks with a (at least somewhat) common outlook that specified above all honesty and a “government of laws, not men”. I would also state that this is a good bit of our problem now.

This is a great observation. An anthropologist by the name of Maya Mikdashi recently wrote an article on the effects of market-based reforms in the Middle East. She essentially argued that the market-based reforms assume that only a certain type of individual can successfully participate in the market economy (stay with me here): the rational, autonomous, freedom-seeking, and legally-protected-as-an-individual type. Over the past two decades, as more states have moved towards a market-based economy, we have seen the institutional and cultural rewards being reaped from this process. Instead of people who have known only poverty and want, the market-based economy has pushed individuals to seek to become more rational, autonomous, freedom-seeking, and legally protected as an individual.

Now, stay with me. The market-based economy, capitalism, has four broad institutional pillars that it needs to thrive: private property, individualism, the rule of law, and an internationalist spirit. From these pillars come the fountains of progress that the West has come to enjoy over the past 300 years. While I doubt she realizes it, Mikdashi is simply echoing the writings of the great classical liberal theorists of the past three centuries: institutions matter, and they matter a lot. A big point both Dr. Ayittey and myself have been trying to make is that the institutions necessary for progress and capitalism are already in place in the post-colonial world; when I was in Ghana doing research one of the things I always asked farmers is where they got their property titles and they answered “the chief.” I asked them why they didn’t go through more official routes to obtain their property titles (i.e. through the state), and I’m sure you can finish the Ghanaian farmer’s answer for him.

The fact that most, if not all, citizens of the new republic desired the rule of law is one that cannot be stressed enough, and it is definitely one of the reasons why we have grown so prosperous, and answers why we are in trouble today. However: Africans don’t desire the rule of law?

Is It Time to Reject African States?

That is essentially what a political scientist is arguing in a short piece in the New York Times:

Yet because these countries were recognized by the international community before they even really existed, because the gift of sovereignty was granted from outside rather than earned from within, it came without the benefit of popular accountability, or even a social contract between rulers and citizens.

Imperialists like Dr Delacroix and Nancy Pelosi don’t seem to care about the legitimacy of post-colonial states (largely, I suspect, because they thought they did a great job of creating the borders that they did). You never hear them make arguments like this. Instead, the imperial line is all about helping all of those poor people suffering under despotic rule by bombing their countries, just as you would expect a condescending paternalist to do.

Since tactical strikes and peacekeeping missions have utterly failed since the end of WW2, why not try a new tactic? Our political scientist elaborates:

The first and most urgent task is that the donor countries that keep these nations afloat should cease sheltering African elites from accountability. To do so, the international community must move swiftly to derecognize the worst-performing African states, forcing their rulers — for the very first time in their checkered histories — to search for support and legitimacy at home […]

African states that begin to provide their citizens with basic rights and services, that curb violence and that once again commit resources to development projects, would be rewarded with re-recognition by the international community.

Englebert (the political scientist) goes on use examples of democratization in Taiwan as an example of how delegitimizing states can lead to democratization.

Another interesting angle that Englebert brings in is that of Somaliland, a breakaway region of Somalia that has not been recognized by the international community and, perhaps as result of this brittle reception by the international community, it is flourishing economically and politically. You won’t hear imperialists point to Somaliland either. Instead, you’ll get some predictable snark about ‘anarchism‘ or African savagery from these paternalists.

Yet, it is obvious that Somaliland is neither anarchist nor savage, as there is a government in place that is actively trying to work with both Mogadishu and international actors on the one hand, and rational calculations made by all sorts of actors on the other hand. What we have in the Horn of Africa, and – I would argue – by extension elsewhere in the post-colonial world, is a crisis of legitimacy wrought by the brutal, oppressive hand of government.

The Case for More States in Africa? Anarchy, State or Utopia?

Yes please! There is an old article in the Atlantic arguing that more states are just what Africa needs, and I’d like to highlight why I think more states are a good thing, and at the same time pick up Dr. Delacroix’s argument on states and libertarianism from a little while back and explain why I think that more states are a good thing and why Dr. Delacroix doesn’t really understand libertarian thought.

Now, I know more states seems at first glance to be a counterintuitive position for a libertarian to take, but upon second glance I hope to show you why this isn’t true.

First up, from the Atlantic‘s article:

The idea that Africa suffers from too few secessionist campaigns, too few attempts to carve a few large nations into many smaller ones, flies in the face of conventional wisdom. One of the truisms of African politics is that traditional borders, even when bequeathed by colonizers without the least sympathy for African political justice, ought to be respected. The cult of colonial borders has been a cornerstone not only of diplomacy between African nations but of the assistance programs of foreign governments and multinational non-governmental organizations.

I’ve pointed this out from a number of different angles previously here on the blog, so I don’t want to delve too deeply into this, but the article, written by a professor of journalism at Arizona State, has more: Continue reading

Property Rights in Africa: More Decentralization Please

From the economist Camilla Toulmin:

While land registration is often proposed as a means of resolving disputes, the introduction of central registration systems may actually exacerbate them. Elite groups may seek to assert claims over land which was not theirs under customary law, leaving local people to find that the land they thought was theirs has been registered to someone else. The high costs of registration, in money, time, and transport, make smallholders particularly vulnerable to this.

You can read the rest of her article here [ungated version can be found here]. It goes on to elaborate upon how more decentralization is needed, as well as the need for more incorporation of indigenous legal practices. Highly recommended, but grab a cup of coffee first.

Arguments to ponder:

- James Buchanan’s work on public choice (elite groups seeking to capture the rent)

- Friedrich Hayek’s work on tacit knowledge and the inability to plan societies from the top

- Elinor Ostrom’s work on governing the commons and how states muddle the intricate “rules of the game”

Any thoughts? Suggestions for further reading?

Property Rights in the Post-Colonial World

Land grabs and crony capitalism at its finest. From Reason magazine:

Politicians in the affected countries are key partners in operations that resemble the late-19th-century scramble for control of Africa. The land grabs aim at enriching privileged companies and their political allies, usually at the expense of those already on the land. States, companies, and their frequent close friend, the World Bank, see no reason to respect sitting owners and resource users, whatever their rights under customary law and (sometimes) postcolonial statutes. Pastoral nomads get even less respect. In Tanzania, for example, governments and safari capitalists have reduced the traditional grazing lands of the Maasai herdsmen to a fraction of what they were. And in Ethiopia, the government’s “villagization” policy, Pearce writes, resettles peasant farmers “in the manner of Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot,” clearing the way for deals with foreign capital.

You can read the rest here. I hope to have some more academic articles up as links soon.

Around the Web

- Secessionist Movements in Europe. I have always thought that the EU would be great for more decentralization, but once the central bank became established and Brussels agitated for more political power I knew that the experiment in confederation would become the failure that it is today.

- Economist Bryan Caplan on Left-wing historical bias and Benito Mussolini. You’d be surprised what the history books keep out of Italy’s socialist movement…

- Has Africa Always Been the World’s Poorest Continent? Be sure to read through the ‘comments’ section too.

- Mini-DREAM and the Rule of Law: Executive Discretion. A number of libertarians have come out in support of Obama’s executive order prohibiting immigrants from being deported just for moving here as children, but I am not so sure that this is a good move. Politically, it’s great, especially when one considers the fact that the Obama administration has deported more immigrants in 4 years than GW Bush did in 8. I am more worried about the Rule of Law. It’s the legislative branch’s job to implement immigration policy, not the executive branch’s. As somebody who supports open borders, this is a tough call.

Secession, Small States, and Decentralization: A Rejoinder to Dr. Ayittey

Dr Ayittey has kindly responded to my rebuttal.

You can’t mix secession with decentralization of power; oranges and apples. Your statements that “Smaller states would be much better for Africa than the large ones in place” and “The more “Little Djiboutis” there are, the better” are ridiculous. At a time when small countries are coming together to form larger economic blocs – EU, AU, ASEAN, Mercosur, etc. – you recommend going in the other direction: The creation of more little states that are not economically viable. Would you recommend the break-up of the US into 50 little states? Check your own history.

The original US Constitution was inspired by the Iroquois Confederacy. Under that Constitution, the South elected to secede, which led to the Civil War (1861-1865). Why didn’t the US allow the South to secede? It would have led to GREATER decentralization of power.

Now, I want to let everybody know that this exchange is happening over Twitter, so be sure to take Dr. Ayittey’s response in stride and in context.

First up are his first and last statements: Continue reading

African Political Structures: A Debate

I just hooked a big fish on the end of my line when I tweeted about my support for secession of Azawad to Dr. George Ayittey, an economist at American University and one of Africa’s leading lights of classical liberalism. I have a talent for ribbing people in just the right place at just the right time, and the following response I got from Dr. Ayittey confirms my magnificent talent (some may disagree with the label ‘talent’, but I digress).

In response to my support for Azawad, Dr. Ayittey tweeted the following: Continue reading

Catching the Killer Kony: What Trends for Tools Can Tell Us About Political Structures

I am more than amused at the current trend of teenage boppers and serious college students catching up with the decades-long war happening in the Congo basin. It makes feel superior! If we really want to solve the problem of war in the Congo basin (and everywhere else in the post-colonial world) then we are going to have start looking at the political structures that have been left behind by the colonialists and enhanced by the indigenous (and socialist-educated) elite.

I have a quick blurb that may be of use. I say “may be” because I have decided to use Nigeria as an example rather than Uganda because it is a region I am much more familiar with, but the underlying concept is still the same. My more intelligent readers will no doubt grasp this nuance right away, but it may be harder to grasp for those readers not well-versed in social theory. I would, as always, be grateful for critiques and comments alike.

Religion has virtually nothing to do with the current conflict tearing Nigeria apart, and everything to do with the legacy of British imperialism (which went hand-in-hand with socialist legislation in the late decades of the 19th century). Continue reading