- The costs of hospital protectionism Chris Pope, National Affairs

- Parasitic SETI and parasitic space science Nick Nielsen, Grand Strategy Annex

- Between two empires (Armenia) Peter Brown, New York Review of Books

- The transition from socialism to capitalism Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

Selective Moral Argumentation

There are two competing approaches to moral theory. Consequentialism posits that actions and policies should be judged by their consequences: an action (or policy) is good if its predictable consequences are good. Deontologist perspectives, on the other hand, claim that actions should be judged according to their own worth, irrespective of consequences.

Note that the differences between these approaches lies not in the specific policies advocated but in their modes of arguing. Consider the death penalty. Consequentialists are generally against killing people because it’s not a good idea, but will support the death penalty if it can be shown that it is a cost-effective way of reducing crime. The deontologist opposition against the death penalty is absolute, but a deontologist may also support the death penalty because criminals deserve it, even if that’s not an efficient way to reduce crime.

I used to believe that specific individuals are either consequentialists or deontologists, i.e. some people are very sensitive to consequentialist reasoning while others were immune to it, and vice versa. At the very least, I expected individuals to combine both approaches in a consistent way (for example, by being consequentialists only two-thirds of the time). But now I think this is putting the cart before the horses: what happens in practice is that an individual first decides which policy she wants to defend, and then employs the mode of argument that is more favorable to the policy in question.

Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, right-wing military dictatorships were pretty common in Latin America. These governments often committed heinous crimes. When, years or even decades after the fact, the issue of punishing those responsible came to the fore, right-wingers opposed the move from a consequentialist perspective –social peace is worth preserving, isn’t it?–, while left-wingers took the deontologist stance –surely those who committed crimes against humanity should be harshly punished. But when the discussion turned about pardoning left-wing guerrillas, as in the 2016 peace referendum in Colombia, the tables turned: now the right found intolerable that criminals would be pardoned for the sake of social peace. (It is worth noting that in Argentina, where several former military commanders, including some with atrocious human rights records, contested and won elections after the return to democracy, the right never raised deontologist objections against them.)

I see the same pattern in Mexico today. During the electoral campaign last year, then candidate Andrés Manuel López Obrador was harshly criticized for raising the possibility of an amnesty for members of drug cartels in order to pacify the country. To be sure, there are many ways in which such a strategy could go wrong; but the criticism focused on the moral horror of pardoning drug dealers. Predictably, now that the government of López Obrador cut fuel supplies in order to prevent gasoline theft –something against which his predecessors had done nothing–, his opponents have found the virtues of consequentialism: the policy is creating (serious) fuel shortages. As you may guess, the government highlights the importance of combating criminals, without paying much attention to the consequences.

All of this reinforces the point repeatedly made by Cowen and Hanson: politics is not about policy, but about the relative status of different social groups. That said, the fact that we (unconsciously?) pick our preferred policies/stances first and decide how to defend them afterwards only begs the question: what determines whether we end up positioning ourselves in one side of the political spectrum or another? And given that we sometimes (but rarely) switch sides, what are the motivations behind these changes?

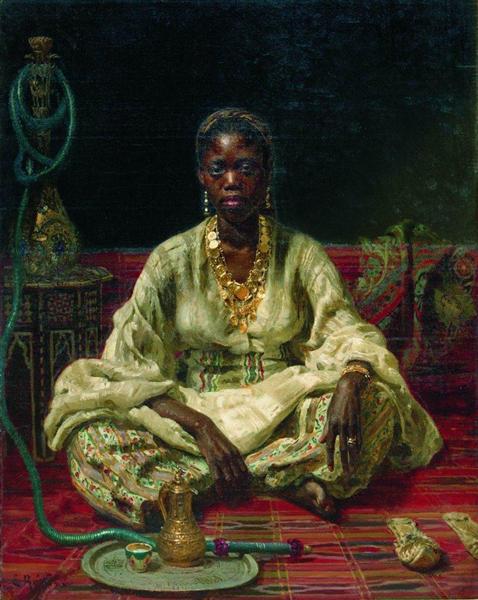

Afternoon Tea: Negress (1876)

This is from Russian painter Ilya Repin:

Southeast Asia, China, and Trumpian foreign policy in 2019

A survey titled, ‘State of Southeast Asia: 2019’ conducted by the ASEAN Studies Centre (between November 18 and December 5, 2018 and released on January 7, 2019) at the think-tank Iseas-Yusof Ishak Institute came up with some interesting findings. The sample size of the survey was over 1,000 and consisted of policy makers, academics, business persons, and members of civil society from the region.

It would be fair to say that some of the findings of the survey were along expected lines. Some of the key points highlighted are as follows:

According to the survey, China’s economic clout and influence in South East Asia is steadily rising, and it is miles ahead of other competitors. Even in the strategic domain, Washington’s influence pales in comparison to that of Beijing’s. As far as economic influence in South East Asia is concerned, a staggering 73 percent of respondents subscribed to the view that China does not have much competition. A strong reiteration of this point is the level of bilateral trade between China and ASEAN (Association of Southeast Asian Nations), which comfortable surpassed $500 billion in 2017. After China, it is not the US, but ASEAN which has maximum economic clout in the region. If one were to look at the strategic and political sphere, 45% of respondents opined that China is the most influential player in South East Asia, followed by the US at 30 percent.

Second, China’s increasing influence does not imply that it is popular in South East Asia. In fact, a large percentage of the respondents expressed the opinion that China’s lack of integration with global institutions is not a very positive omen. South East Asian nations also have clear reservations with regard to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). 50% of respondents believed that the project would increase ASEAN countries dependence upon China, and there were serious apprehensions, with one third of respondents raising question marks with regard to the transparency of the project. A small percentage of respondents (16%) also felt that the BRI was bound to fail. Many ASEAN countries have been alluding to some of the shortcomings of the BRI, of course none was as vocal as Malaysian Premier Mahathir Mohammad. In the survey, respondents from Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines expressed the view that their countries should be cautious with regard to the BRI. Interestingly, even respondents from Cambodia, a country where China has made significant inroads, Japan is the most trusted country and not China.

Third, US isolationism, especially under Trump, has led to an increasing disillusionment with Washington DC in the region. The current administration has been aggressive on China, and it has sought to take forward former US President Barack Obama’s vision of ‘Pivot to Asia’ in the form of the Indo-Pacific Narrative. Senior voices within the Trump Administration, including current Secretary of State Mike Pompeo, have been trying to give a push to the Indo-Pacific Narrative and reaching out to South East Asian Countries. In July for instance, while addressing the Indo-Pacific Economic Forum at the US Chamber of Commerce in Washington, Pompeo said that the US was going to invest $113 million in new U.S. initiatives in areas like the digital economy, energy, and infrastructure. Pompeo also stated that these funds were a ‘down payment on a new era in U.S. economic commitment to peace and prosperity in the Indo-Pacific region’. Pompeo’s address was followed by a visit to South East Asia (Singapore and Indonesia), where he met with leaders from a number of ASEAN countries.

On December 31, 2018, the US also signed the ARIA (Asia Reassurance Initiative Act), which sought to outline increased US economic and security involvement in the Indo-Pacific region. ARIA has flagged US concerns with regard to China’s expansionist tendencies in South East Asia. Other key strategic issues, such as nuclear disarmament on the Korean Peninsula, have also been highlighted.

The Trump Administration has also earmarked $1.5 billion for a variety of programs in East and South East Asia.

Trump’s decision to pull the US out of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) led to a lot of disappointment in the region, with allies like Singapore putting forward their views. Speaking at the ANZ Forum in November 2018, Former Prime Minister of Singapore, Goh Chok Thong stated:

…It is still a superpower but it has become less benign and generous. Its unilateral actions in many areas have hurt allies, friends and rivals alike […] America First is diminishing the global stature, moral leadership and influence of the US.

This view was also echoed by a number of experts who commented on the finding of the survey.

The Former Singapore PM also made the point that Asia needed to recalibrate its policies in order to adjust to the new world order.

ASEAN

What is clearly evident is that ASEAN needs to build a new vision which is in sync with the changing geopolitical situation. While Malaysian PM Mahathir Mohammad, by scrapping Chinese projects and referring to a new sort of colonialism emerging out of China’s BRI project, has taken an important step in this direction, it remains to be seen whether other countries in the region can also play their role in helping ASEAN weave its own narrative. For a long time now, countries have been dependent upon both the US and China, and have thought in terms of choices, but there has never really been a concerted effort to create an independent narrative.

What ASEAN actually needs is a narrative where it does not shy away from taking an independent stance, and where it is also willing to take a stand on issues of global relevance. One such issue is the Rohingya Issue. Apart from Malaysia and Indonesia, none of the other members of ASEAN has taken a clear stand. In the past, many ASEAN countries thought that they could refrain from commenting on contentious issues. Respondents to the survey felt that ASEAN states should be more involved in the Rohingya Issue.

The United States and other countries which are wary of Chinese influence should come up with a feasible alternative. So far, while members of the Trump Administration have repeatedly raised the red flag with regard to China’s hegemonic tendencies, and predatory economics as has been discussed earlier, it has not made the required commitment. While the Trump Administration has not been able to pose a serious challenge to Beijing, it remains to be seen if the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act is effective.

It is also important for Washington, and other countries, not to look at Chinese involvement from a zero-sum approach. Perhaps it is time to adopt a more pragmatic and far sighted approach. If Japan and China can work together in the Belt and Road Initiative, as well as other important infrastructural initiatives in South East Asia, and India and China can work together in capacity-building projects in Afghanistan, the possibility of US and China finding common ground in South East Asia should not be totally ruled out. Amidst all the bilateral tensions, recent conversation between US President Donald Trump and Chinese President Xi Jinping, and statements emanating from both sides are encouraging.

Conclusion

An isolationist Washington DC and a hegemonic Beijing are certainly not good news, not just for ASEAN, but for other regions as well. The survey has outlined some of the key challenges for ASEAN, but it is time now to look for solutions. Hopefully, countries within the region will shape an effective narrative, and be less dependent upon the outside world. The survey is important in highlighting some broad trends but policy makers in Washington as well as South East Asia need to come up with some pragmatic solutions to ensure that Beijing does not have a free run.

RCH: Cassius Clay as the “greatest American” of the 20th century

My latest at RealClearHistory:

It was also the heyday of the Cold War, a nearly 50-year struggle for power between the liberal-capitalist United States and the socialist Soviet Union. The struggle was real (as the kids say today). The United States and its allies were losing, too, at least in the realm of ideas. The Soviet Union was funding groups that would today be considered progressive — anti-racist and anti-capitalist — around the world. One of the sticks that Moscow used to beat the West with was racism in the United States, especially in the officially segregated South.

It is doubtful that most of the African-American groups who took part in the struggle for liberty were funded, or even indirectly influenced by Soviet propaganda. The clear, powerful contrast between black and white in the United States was enough for most African-Americans to take part in the Civil Rights revolution. Yet Soviet propaganda still pestered Washington, and Moscow wasn’t wrong.

Please, read the rest.

Nightcap

- Bringing natural law to international relations Samuel Gregg, Law & Liberty

- How to face down the Secret Service Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Affirmative Action at Harvard and statistics Gelman, Goel, & Ho, Boston Review

- The right’s triumph; the Left’s complicity Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

The Yellow Vests: Update

In the ninth weekend of demonstrations, the politics of envy seem to dominate. (Soak the rich again!) The Government must give us more money. Lower some taxes but impose or re-impose others especially the former tax on wealth.

Far behind: Introduce a degree of popular initiative in the political process: allow groups of citizens to initiate legislation, to implement it, and to abrogate it.

I can’t tell if those who want more money are the same as those who demand popular initiative in legislation. It’s a problem with grass root movements. They make attribution difficult.

Pres. Macron’s response is all over the place. It sounds like the work of an old man although the pres. is only 41. I think I know why this is: Nearly all the past thirty presidents and prime ministers are graduates from the one same school. Maybe they just crib the class notes of their predecessors.

Notably, Mr Macron’s response – contained in an open letter – to the nation includes more “save the Planet” proposals as if he had forgotten that an environmentalist tax set the barrels of powder on fire to begin with. Little chance he will be heard by the Yellow Vests although his open letter may serve to rally the main part of the population around him as the lesser of several evils.

Notably, the president, on his own, mentioned the possibility of limiting immigration although that’s not high in any of the Yellow Vests demands. Curious.

The president’s proposed themes are supposed to be debated widely and on a national scale. They are expected to give rise to suggestions on how to govern France. The suggestions will be collected at the municipal level (a good idea; the French like their mayors) in complaint books called “cahiers de doléances.” The latter sounds to me like a very bad idea. The last time those words were used on a large scale, was around 1788-89. The ruling circles lost their heads soon afterwards. (I mean literally.)

Keep things in perspective: If you add all the demonstrators nationally in every town any Saturday, you arrive at a very small number although it’s made up of persistent people . They are persistent because they represent a large minority facing serious, possibly unsolvable problems. Many ordinary French people have grown weary of the disruptions the Yellow Vests have caused. There is also huge revulsion against the acts of violence that accompany Yellow Vests demonstrations (not necessarily their own acts).

Cool heads counsel the president to dissolve the National Assembly and to call for new elections. Supposedly, this would bring up elected representatives more in tune with the people’s mood. My own guess is that new elections would result in the isolation of the Yellow Vests and bring an end to their movements. Just guessing.

Did I forget anything?

Nightcap

- The left-wing case against open borders Angela Nagle, American Affairs

- A classic account of travel in Laos Peter Gordon, Asian Review of Books

- The remarkable rise of John Lilburne Jackie Eales, History Today

- The dilemma of India’s undersea nuclear weapons Yogesh Joshi, War on the Rocks

A humorous aside, out of context

<Scene: A wood-paneled study where a smartly-dressed person sits reading aloud from an oversized King James Bible.>

“Isaiah 9:7 – Of the increase of government … there shall be no end… .”

<Our hero pauses, turns to the camera and deadpans.>

“You got that right, brother!”

<Exeunt>

Immigration: Not Opinions, Facts

Immigration is in our newspapers and on our screens every day. Yet, between the factual confusion of most Republicans and the insult-laden cheery irresponsibility of Democrats, little of substance is being said. Here are two central facts that are routinely ignored:

1 In practice, there is no legal path to immigration for 95% + of illegal immigrants. Asylum is a possibility for a tiny number among them. Poverty is not currently grounds for asylum. (See reference below.)

2 A forty year-old single immigrant from India with an engineering degree is unlikely to take more out of the public trough than he puts in. He is also very unlikely to commit a serious crime, especially a serious crime of violence. Now, consider younger immigrants from Central America, who have have few or no skills, who don’t know English, who may be semi-literate, or even illiterate in their own language. If they are female, they will probably cause a draw on the public treasury, if nothing else by sending to school children with special (linguistic) requirements, while contributing little to the financial maintenance of the same schools. That’s the optimistic case, where the children are healthy and normal.

If they are male, they will add to American crime, especially to violent crime because that’s the way it works: Younger, poor men, of no or low literacy are responsible for almost all of the violent crime in America. Note that this pronouncement does not contradict the findings of the excellent article by Michael T. Light and Ty Miller “Does Undocumented Immigration Increase Violent Crime?” published in the Journal Criminology, March 18th 2018. The study on which they report finds that an influx of illegal immigrants does not correspond to a higher crime rate. (Note: It’s a good study by any criteria – I am credentialed to judge.)

The point – beyond the sterile debate about immigrants’ crime rates – is that immigrants of the “right” (wrong) characteristics do not replace the native born one-for-one, including in the commission of crimes. They contribute their own deeds. Take the young California police officer named Singh who was murdered by a crime recidivist illegal alien in early 2019. If Officer Singh had not encountered his particular illegal alien killer, does anyone think that a citizen, or a legal alien would have stepped in to murder him?

This is an abstracted summary from my longer, informational essay on immigration: “Legal Immigration Into the United States.”

Afternoon Tea: The waterfall of Amida behind the Kiso Road (1827)

From the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai:

Nightcap

- The art of bullshit detection, as a way of life Joshua Hochschild, First Things

- On the mind-body and consciousness-body problems Nick Nielsen, Grand Strategy Annex

- Lost innocence: the children whose parents joined an ashram Lily Dunn, Aeon

- Polish mayor, a centrist, was just stabbed at a charity event Jan Cienski, Politico

Nightcap

- Gilets Jaunes and the age of commuter democracy Andrew Smith, Age of Revolutions

- Victor Klemperer’s dispatches from interwar Germany Peter Gordon, the Nation

- Harold Demsetz (1930-2019) and UCLA price theory Peter Boettke, Coordination Problem

- The rise and fall of the British nation Richard Davenport-Hines, Times Literary Supplement

In Defense of Not Having a Clue

Timely, both in our post-truth world and for my current thinking, Bobby Duffy of the British polling company IPSOS Mori recently released The Perils of Perception, stealing the subtitle I have (humbly enough) planned for years: Why We’re Wrong About Nearly Everything. Duffy and IPSOS’s Perils of Perception surveys are hardly unknown for an informed audience, but the book’s collection and succint summary of the psychological literature behind our astonishingly uninformed opinions, nevertheless provide much food for thought.

Producing reactions of chuckles, indignation, anger, and unseeming self-indulgent pride, Duffy takes me on a journey of the sometimes unbelievably large divergence between the state of the world and our polled beliefs about the world. And we’re not primarily talking about unobservable things like “values” here; we’re almost always talking about objective, uncontroversial measures of things we keep pretty good track of: wealth inequality, share of immigrants in society, medically defined obesity, number of Facebook accounts, murder and unemployment rates. On subject after subject, people guess the most outlandish things: almost 80% of Britons believed that the number of deaths from terrorist attacks between 2002 and 2016 were more or about the same as 1985-2000, when the actual number was a reduction of 81% (p. 131); Argentinians and Brazilians seem to believe that roughly a third and a quarter of their population, respectivelly, are foreign-born, when the actual numbers are low single-digits (p. 97); American and British men believe that American and British women aged 18-29 have had sex as many as 23 times in the last month, when the real (admittedly self-reported) number is something like 5 times (p. 57).

We can keep adding astonishing misperceptions all day: Americans believe that more than every third person aged 25-34 live with their parents (reality: 12%), but Britons are even worse, guessing almost half (43%) of this age bracket, when reality is something like 14%; Australians on average believe that 32% of their population has diabetes (reality more like 5%) and Germans (31% vs 7%), Italians (35% vs 5%), Indians (47% vs 9%) and Britons (27% vs 5%) are similarly mistaken.

The most fascinating cognitive misconception is Britain’s infected relationship with inequality. Admittedly a confusing topic, where even top-economists get their statistical analyses wrong, inequality makes more than just the British public go bananas. When asked how large a share of British household wealth is owned by the top-1% (p. 90), Britons on average answered 59% when the reality is 23% (with French and Australian respondents similarly deluded: 56% against 23% for France and 54% against 21% for Australia). The follow-up question is even more remarkable: asked what the distribution should be, the average response is in the low-20s, which, for most European countries, is where it actually is. In France, ironically enough given its current tax riots, the respondents’ reported ideal household wealth proportion owned by the top-1% is higher than it already is (27% vs 23%). Rather than favoring upward redistribution, Duffy draws the correct conclusion:

“we need to know what people think the current situation is before we ask them what they think it should be […] not knowing how wrong we are about realities can lead us to very wrong conclusions about what we should do.” (p. 93)

Another one of my favorite results is the guesses for how prevalent teen pregnancies are in various countries. All of the 37 listed countries (p. 60) report numbers around less than 3% (except South Africa and noticeable Latin American and South-East Asian outliers at 4-6%), but respondents on average quote absolutely insane numbers: Brazil (48%), South Africa (44%) Japan (27%), US (24%), UK (19%).

Note that there are many ways to trick people in surveys and report statistics unfaithfully and if you don’t believe my or Duffy’s account of the IPSOS data, go figure it out for yourself. Regardless, is the take-away lesson from the imagine presented really that people are monumentally stupid? Ignorant in the literal sense of the world (“uninstructed, untututored, untaught”), or even worse than ignorant, having systematically and unidirectionally mistaken ideas about the world?

Let me confess to one very ironic reaction while reading the book, before arguing that it’s really not the correct conclusion.

Throughout reading Duffy’s entertaining work, learning about one extraordinarily silly response after another, the purring of my self-indulgent pride and anger at others’ stupidity gradually increased. Glad that, if nothing else, that I’m not as stupid as these people (and I’m not: I consistently do fairly well on most questions – at least for the countries I have some insight into: Sweden, UK, USA, Australia) all I wanna do is slap them in the face with the truth, in a reaction not unlike the fact-checking initiatives and fact-providing journalists, editorial pages, magazines, and pundits after the Trump and Brexit votes. As intuitively seems the case when people neither grasp nor have access to basic information – objective, undeniable facts, if you wish – a solution might be to bash them in the head or shower them with avalanches of data. Mixed metaphors aside, couldn’t we simply provide what seems to be rather statistically challenged and uninformed people with some extra data, force them to read, watch, and learn – hoping that in the process they will update their beliefs?

Frustratingly enough, the very same research that indicate’s peoples inability to understand reality also suggests that attempts of presenting them with contrary evidence run into what psychologists have aptly named ‘The Backfire Effect’. Like all force-feeding, forcing facts down the throats of factually resistent ignoramuses makes them double down on their convictions. My desire to cure them of their systematic ignorance is more likely to see them enshrine their erroneous beliefs further.

Then I realize my mistake: this is my field. Or at least a core interest of the field that is my professional career. It would be strange if I didn’t have a fairly informed idea about what I spend most waking hours studying. But the people polled by IPSOS are not economists, statisticians or data-savvy political scientists – a tenth of them can’t even do elementary percent (p. 74) – they’re regular blokes and gals whose interest, knowledge and brainpower is focused on quite different things. If IPSOS had polled me on Premier League results, NBA records, chords or tunes in well-known music, chemical components of a regular pen or even how to effectively iron my shirt, my responses would be equally dumbfunded.

Now, here’s the difference and why it matters: the respondents of the above data are routinely required to have an opinion on things they evidently know less-than-nothing about. I’m not. They’re asked to vote for a government, assess its policies, form a political opinion based on what they (mis)perceive the world to be, make decisions on their pension plans or daily purchases. And, quite a lot of them are poorly equipped to do that.

Conversely, I’m poorly equipped to repair literally anything, work a machine, run a home or apply my clumsy hands to any kind of creative or artful endeavour. Luckily for me, the world rarely requires me to. Division of Labor works.

What’s so hard with accepting absence of knowledge? I literally know nothing about God’s plans, how my screen is lit up, my car propels me forward or where to get food at 2 a.m. in Shanghai. What’s so wrong with extending the respectable position of “I don’t have a clue” to areas where you’re habitually expected to have a clue (politics, philosophy, virtues of immigration, economics)?

Note that this is not a value judgment that the knowledge and understanding of some fields are more important than others, but a charge against the societal institutions that (unnaturally) forces us to. Why do I need a position on immigration? Why am I required (or “entitled”, if you believe it’s a useful duty) to select a government, passing laws and dealing with questions I’m thoroughly unequipped to answer? Why ought I have a halfway reasonable idea about what team is likely to win next year’s Superbowl, Eurovision, or Miss USA?

Books like Duffy’s (Or Rosling’s, or Norberg‘s or Pinkers) are important, educational and entertaining to-a-t for someone like me. But we should remember that the implicit premium they place on certain kinds of knowledge (statistics and numerical memory, economics, history) are useful in very selected areas of life – and rightly so. I have no knowledge of art, literature, construction, sports, chemistry or aptness to repair or make a single thing. Why should I have?

Similarly, there ought to be no reason for the Average Joe to know the extent of diabetes, immigration or wealth inequality in his country.

Nightcap

- Thoughtcrime and punishment at a Canadian university Lindsay Shepherd, Quillette

- The prophet of envy Robert Pogue Harrison, New York Review of Books

- Ominous parallels? Stephen Cox, Liberty Unbound

- Georges Washington & Marshall: Two studies in virtue David Hein, Modern Age