On standard tests of empathy, libertarians score very low. Yet, the world’s “well-known libertarian bias” coupled with many people’s unwarranted pessimism makes us seem like starry-eyed optimists (“how could you possibly believe things will just work themselves out?!”).

Under the Moral Foundations framework developed and popularized by Jonathan Haidt, he and his colleagues analyzed thousands of responses through their YourMorals.org tool. Mostly focused on what distinguishes liberals from conservatives, there are enough self-reported libertarians answering that the questionnaire to draw meaningful conclusions. The results, as presented in TED-talks, podcast interviews and Haidt’s book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics and Religion contains a whole lot of interesting stuff.

First, some Moral Foundations basics: self-reported liberals attach almost all their moral value to two major categories – “fairness” and “care/harm.” Some examples include striving for equal (“fair”) outcomes and concern for those in need. No surprises there.

Conservatives, on the other hand, draw fairly evenly on all five of Haidt’s different moralities, markedly placing weight on the other three foundations as well – Authority (respect tradition and your superiors), Loyalty (stand with your group, family or nation) and Sanctity (revulsion towards disgusting things); liberals largely shun these three, which explains why the major political ideologies in America usually talk past one another.

Interestingly enough, In The Righteous Mind, Haidt discusses experiments where liberals and conservatives were asked to answer the questionnaire as the other would have. Conservatives and moderate liberals could represent the case of the other fairly well, whereas those self-identifying as “very liberal” were the least accurate. Indeed, the

biggest errors in the whole study came when liberals answered the Care and Fairness questions while pretending to be conservatives.

Within the Moral Foundations framework, this makes perfect sense. Conservatives have, in a sense, a wider array of moral senses to draw from – pretending to be liberal merely means downplaying some senses and exaggerating others. For progressives who usually lack any conception of the other values, it’s hard to just invent them:

if your moral matrix encompasses nothing more than Care and Fairness, then to imagine a political opponent is to reverse one’s own position for those foundations – that Conservatives act primarily on other frequencies, on other foundations, wouldn’t even occur to them.

Libertarians, always the odd one out, look like conservatives on the traits most favoured by liberals (Fairness and Care/Harm); and are indistinguishable from liberals on the traits most characteristic of conservatives (Authority, Loyalty, and Sanctity). Not occupying some fuzzy middle-ground between them, but an entirely different beast.

Empathy, being captured by the ‘Care’ foundation, lines up well with political persuasion, argues Yale psychologist Paul Bloom in his Against Empathy: The Case for Rational Compassion. Liberals care the most; conservatives some; and libertarians almost none at all. Liberals are the most empathic; conservatives are somewhat empathic; and libertarians the least empathic of all. No wonder libertarians seem odd or positively callous from the point of view of mainstream American politics.

Compared to others, libertarians are more educated and less religious – even so than liberals. Libertarians have “a relatively cerebral as opposed to emotional cognitive style,” concluded Haidt and co-authors in another study; they are the “most cerebral, most rational, and least emotional,” allowing them more than any others to “have the capacity to reason their way to their ideology.”

Where libertarians really do place their moral worth is on “liberty” (a sixth foundation that Haidt and his colleagues added in later studies). Shocking, I know. Libertarians are, in terms of moral philosophy, the most unidimensional and uncomplicated creatures you can imagine – a well-taught parrot might pass a libertarian Turing test if you teach it enough phrases like “property rights” or “don’t hurt people and don’t take their stuff.”

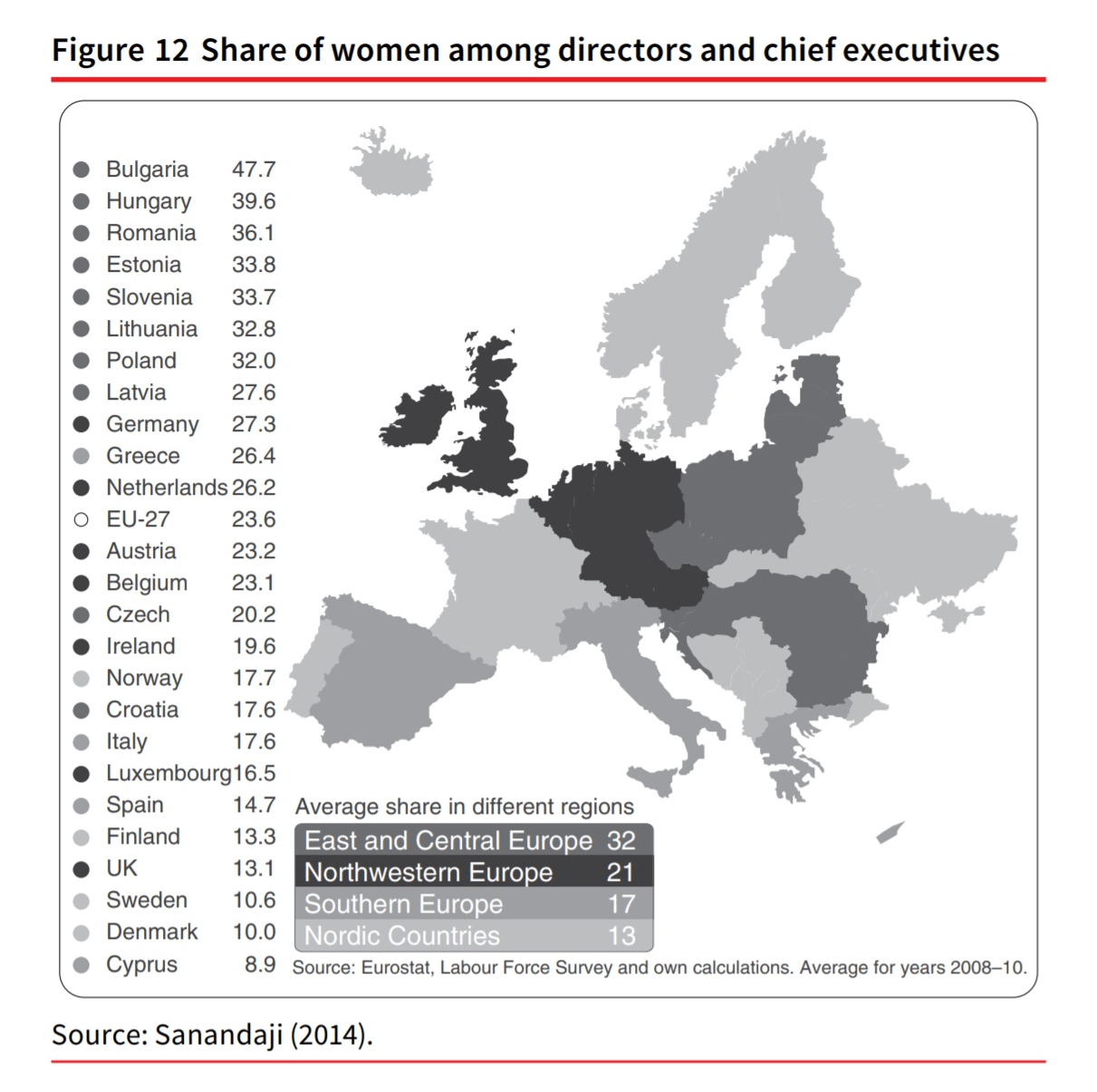

The low-empathy result accounts for another striking observation to anyone who’s ever attended an even vaguely libertarian event: there are very few women around. As libertarians also tend to be ruthlessly logical and untroubled by differential outcomes along lines of gender or ethnicity – specifically in small, self-selected samples like conferences – they are usually not very bothered by the composition of their group (other than to lament the potential mating opportunities). The head rules, not the heart – or in this case, not even the phallus.

One of the most well-established (and under-appreciated) facts in the scientific community is the male-female divide along Simon Baron-Cohen’s Empathizing-Systemizing scale. The observation here is that males more often have an innate desire to understand entire systems rather than individual components – or the actions or fates of those components: “the variables in a system and how those variables govern the behaviour of that system,” as Haidt put it in a lecture at Cato. Examples include subway maps, strategy games, spreadsheets, or chess (for instance, there has never been a female world champion). Women, stereotypically, are much more inclined to discover, understand, mirror and even validate others’ feelings. Men are more interested in things while women are more concerned with people, I argued in my 2018 Notes post ‘The Factual Basis of Political Opinion’, paraphrasing Jordan Peterson.

The same reason that make men disproportionately interested in engineering – much more so than women – also make men more inclined towards libertarianism. A systemizing brain is more predisposed to libertarian ideology than is the empathizing brain – not to mention the ungoverned structure of free markets, and the bottom-up decentralized solutions offered to widespread societal ills.

Thus, we really shouldn’t be surprised about the lack of women in the libertarian ranks: libertarians are the least empathic bunch, which means that women, being more inclined towards empathy, are probably more appalled by an ideology that so ruthlessly favours predominantly male traits.

As I’ve learned from reading Bloom’s book, empathy – while occasionally laudable and desirable among friends and loved ones – usually drives us towards very poor decisions. It blinds us and biases us to preferring those we already like over those far away or those we cannot see. The “spotlight effect” that empathy provides makes us hone in on the individual event, overlooking the bigger picture or long-term effects. Bloom’s general argument lays out the case for why empathy involves in-group bias and clouds our moral judgements. It makes our actions “innumerate and myopic” and “insensitive to statistical data.” Empathy, writes Bloom:

does poorly in a world where there are many people in need and where the effects of one’s actions are diffuse, often delayed, and difficult to compute, a world in which an act that helps one person in the here and now can lead to greater suffering in the future.

In experiments, truly empathizing with individuals make us, for instance, more likely to move a patient higher on a donation list – even when knowing that some other (objectively-speaking) more-deserving recipient is thereby being moved down. Empathy implores us to save a visible harm, but ignore an even larger (and later) but statistically-disbursed harm.

Perhaps libertarians are the “the least empathic people on earth.” But after reading Bloom’s Against Empathy, I’m not so sure that’s a bad thing. Perhaps – shocker! – what the world needs is a little bit more libertarian values.