- The original meaning of the 14th Amendment Damon Root, Reason

- Understanding politics today Stephen Davies, Cato Unbound

- It sometimes begins with Emerson Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- RealClearHistory‘s 10 best history films of 2018

Year: 2018

Damares Alves and the left’s hypocrisy

The last polemic in Brazilian politics was due to a testimony of Damares Alves, chosen by Jair Bolsonaro to be his minister of human rights. In a video that is available on YouTube, during a religious service, Damares tells how in her childhood, between 6 and 8 years of age, she was systematically sexually abused by someone close to her family (some sources I found say that the abuser was her uncle). To add to the sexual abuse, the criminal also exploited her psychologically: he told Damares that if she denounced him, he would kill her father. He also said, taking advantage of the religious beliefs of Damares, that she would not go to heaven because she was “impure.”

Damares tells that she unsuccessfully tried to ask for help from people in her family and her church. She would frequently climb a guava tree in her backyard to cry. When she was 10 years old, she climbed that same tree, having rat poison with her, in order to commit suicide. She tells that this is when she saw Jesus, coming to her. Jesus climbed the tree and hugged her. She felt accepted by Jesus, and she gave up the suicidal ideas.

Damares went on to become a lawyer. For many years she has been defending women who like her are victims of sexual abuse. Because of the violence she suffered as a child, she can’t bear children. However, she adopted an Indian child who would otherwise be murdered by her parents – some tribes in the Amazon believe that some children must be murdered at birth due to a series of reasons. Damares saved one of these children.

Someone cut from the video only the part where Damares says that she saw Jesus from the guava tree. The video went viral, and “crazy” is one of the milder insults directed at Damares on social networks.

In sum: the Brazilian left makes fun of a woman who was sexually abused as a child. Damares’ religious faith helped her cope with the pain. To be honest, I am usually skeptic about stories like the one she told. But what does it care? Somehow her faith in Jesus helped her to cope with one of the most horrendous things that can happen to a person. But it seems that Bolsonaro’s political adversaries have no sensitivity not only to a person’s religious beliefs but to the violence women and children suffer. When the violence does not fit their cultural and political agenda, they don’t care.

As I wrote here, Liana Friedenbach, 16 years old, was kidnaped, raped, and killed by a gang led by the criminal Champinha. Defending Liana, Bolsonaro wanted laws to be tougher on rapists. Maria do Rosário did not agree with Bolsonaro, and even called him a rapist. Bolsonaro offended her saying that “even if I was a rapist, I would not rape you.” The left in Brazil stood with Maria do Rosário and condemned Bolsonaro. The same left today mocks a woman who was sexually abused in her childhood, but who grew to help women in similar situations. Instead, they prefer to make jokes about Jesus climbing guava trees.

Nightcap

- Haiti > Cuba David Henderson, EconLog

- When bad government matters Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

- The future of American foreign policy Ashford & Thrall, War on the Rocks

- Sheep without shepherds Ross Douthat, NY Times

Jair Bolsonaro, Maria do Rosário, and the Champinha case

Over a decade ago, in November 2003, Liana Friedenbach, 16 years old (a minor in Brazil law), and Felipe Silva Caffé, 19 years old, were camping in an abandoned farm close to São Paulo.

While they were camping, the couple was found by a group led by Roberto Aparecido Alves Cardoso, aka “Champinha”. Initially, Champinha and his group wanted to steal from the couple. Realizing that they had little to no money, they changed their minds and decided to kidnap Liana and Felipe.

In the first day of captivity, one member of the gang raped Liana. Felipe was killed on the next day with a shot in the back of his head. Liana heard the shot, but the group lied to her saying that her boyfriend was set free. Liana was then raped by other members of the group led by Champinha.

The group never contacted the families asking for a ransom. On the third day, Liana’s family, worried about the lack of contact, called the police, which found the place where the couple was camping, with some of their belongings. Noticing that the police was closing in, Champinha killed Liana with knife strokes.

Champinha, the leader of the group who kidnapped, raped, and murdered Liana, was underage when the crimes happened, and because of that could not be sent to prison. Instead, he was interned in a correction institution.

The crime shocked Brazil. It was answering this crime that Jair Bolsonaro, at the time a congressman, was clamoring for a change in Brazilian law, allowing criminals like Champinha to be prosecuted. Maria do Rosário, a congresswoman from PT, the party of former president and today prisoner Lula da Silva, was opposing Bolsonaro. During their debate, Maria do Rosário called Bolsonaro a raper. Bolsonaro answered “I am a raper? Look, I would not rape you because you don’t deserve it”. Later Bolsonaro explained that he intended to insult Maria do Rosário by saying “even if I was a raper, as you say, I would not rape you because you are too abominable, even for that”.

So that’s it. I hope this helps non-Portuguese speakers who can read English to understand a polemic phrase attributed to Bolsonaro. And I also hope that Brazilian law is changed someday so that justice can be made and criminals like Champinha and his gang get the death penalty for their crimes.

Nightcap

- Against HIPPster regulation Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Is the “culture of poverty” functional? Bryan Caplan, EconLog

- A sex fiend Jacques Delacroix, NOL

- Do we have the historians we deserve? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

Why Cultural Marxism is a big deal for Brazil, and also for you

I already heard the criticism that cultural Marxism is not a real thing. It’s just a scary word, like neoliberalism, that doesn’t mean anything really. Well, for those who think that way, please pay a visit to Brazil.

When I talk about cultural Marxism, here is what I have in mind: I’m not a specialist in Marx or Marxism by any means, but what I understand is that Marx gravitated towards economic theory in his life. He began his intellectual journey more like a general philosopher but ended more like an economist. A very bad economist. Marx’s economic theory in The Capital is based on the premise of the labor theory of value: things cost what they cost depending on how much work it takes to produce them. Of course, this theory does not represent reality. You take the labor theory of value, Marx’s economic theory crumbles down. That is what Mises explained on paper at the beginning of the 20th century and reality proved throughout it everywhere and every time people tried to put Marxism into practice.

Although Marx’s economic theory didn’t work, Marx’s admirers didn’t give up. In Russia Lenin tried to explain that capitalism survived because of imperialism. Many Marxists working in International Relations make a similar claim. In Italy Gramsci tried to explain that capitalism survived because capitalist elites exercise cultural hegemony. The Frankfurt Schools said the same. It is mostly Gramsci and the Frankfurt School, sometimes collectively called critical theory, that I call cultural Marxism.

Marxism arrived in Brazil mainly in the beginning of the 20th century. Very early then, a communist party was founded there. This communist country was initially very orthodox, following whatever Moscow told them to. However, after WWII and especially after the Military Coup of 1964, Brazilian Marxists started to gravitate towards Gramsci. During the Military Dictatorship, many leftists tried to fight guerrillas, but others simply chose to get into universities, newspapers, churches and other places, and try to overthrow capitalism from there.

In general, I am not a great fan of John Maynard Keynes, but there is a quote from him that I absolutely adore: ““Practical men, who believe themselves to be quite exempt from any intellectual influences, are usually the slaves of some defunct economist”. That’s how I see most Brazilian intellectuals. They are of a superficial brand of Marxism. It would certainly be incorrect to call them Marxist in an orthodox sense, but I understand that they are what Marxism has become: something vaguely anti-establishment, anti-capitalism, in favor of big government and very entitled.

Why is this important for you? Because Brazil is the second largest country in America in population, territory, and economy. That’s why. The economy is a win-win game. An economically free, prosperous Brazil would be good for everyone, not just for Brazilians. But that can only happen if we first defeat the mentality that capitalism is bad and that the state should be an instrument for some vague sort of social justice.

Nightcap

- Cultural Marxism and the New Right Neuffer & Paul, Eurozine

- Black soldiers in European wars, 18th century edition Elena Schneider, Age of Revolutions

- A forgotten Indian hero TR Vivek, Pragati

- The treason prosecution of Jefferson Davis Will Baude, Volokh Conspiracy

Nightcap

- Parmesan cheese and Sunbucks Coffee Scott Sumner, EconLog

- In search of the true Dao Ian Johnson, ChinaFile

- The ‘flower men’ of Saudi Arabia Molly Oringer, BBC

- French anti-tax revolts are nothing new Murray Rothbard, Free Market

The Yellow Vests Movement in France

President Macron spoke to the French nation today (12/10/18). He apologized a little for his figurative distance from the rank-and-file. Then he tried to buy some off the yellow vests off with other people’s money. The national minimum monthly wage will rise by about US$113; overtime will not be taxed anymore. You are not going to believe the next appeasement measure he announced. I have a hard time believing it myself but I read it and heard it from several sources. President Macron decreed a significant Christmas bonus for public servants and ordered (I think) private employers to follow suite. The bonus will also be tax-free. I have no idea what effects these measures will have. I suspect the weather has more influence on the yellow vests’ behavior.

The movement began, as most Americans know by now, as a protest against a new extra tax on diesel fuel. It was presented a little breathlessly as a way to save the planet. This is significant in several ways. First, it suggests that a large fraction of the French people do not believe in climate change (like me) or do not care about it. Second, it demonstrates that Mr Macron, probably along with the political class in general, have lost touch with much of their electorate for not realizing the these perceptions. Third, it shows sheer incompetence if not cynicism. Any average thinking person in France could have warned Mr Macron that a tax on diesel is one of the most regressive taxes possible. The transport of ordinary goods in France relies largely on diesel-powered trucks. A tax on diesel proportionately (proportionately) hits the poor more than the prosperous. Perhaps the government thought that those affected were too stupid or too passive to protest.

The government has reversed its decision on the diesel tax but it’s too late. It seems to me the diesel tax was simply a case of the straw that broke the camel back. Fifty years ago, the French gave themselves a wonderful cradle-to-grave summer camp. It’s a real good one, I must say, including a sort of winter camp of free ski vacations for children. (Would I make this up?) This was based on the original idea that “the rich” could be taxed into paying for summer camp. (Sounds familiar?) After two generations, the bills are finally coming due. The definition of “the rich” has been going down fast. Indirect (and therefore regressive) taxes are everywhere. The increase in the tax on diesel was just one of the latest.

The providential and fun state has other consequences. The main one is that it is implicitly anti-business. It protects employees almost completely against being laid off. It’s solicitous of their leisure with a 34 hour week and many many vacations and holidays. French governing circles have become used to celebrating GDP growth rates so low they are considered shameful in America. I think it’s rigorously true that in the past twenty years, unemployment has never gone below 8%. It’s normally been closer to 9% and even 10%. It’s 20% if you are young. I am guessing (guessing) that it’s 40% and up if you are young and your name is Mohammed.

There is worse. In a pattern that will seem familiar to many Americans, there is a big well-being divide between the capital, Paris proper, and the rest of France. Parisians live in a low-density city with good public transport and many employment opportunities. Housing prices and rents are high in Paris, as you might expect. In nearly all of the rest of France, there are few jobs, spotty services. (I am told it’s not uncommon to have to drive 2 hours each way to consult a specialist); hospitals are good but far and few. Many of those charming villages you see from the freeway have not had schools for many years. Housing in the hinterland is cheap. Of course, this is enough to cause people of low means to be stuck where they are.

It’s difficult for foreign reporters to understand the yellow vests movement, for a small reason and for a big one. First, it does seem to be originally a genuine grassroot movement. Accordingly, it has no leaders and not authorized spokespersons. Second, and much more importantly, in my lifetime the very conceptual vocabulary of market economies has vanished from the public discourse. The yellow vests interviewed on television do not know how to express what hurts them. When ordinary French men and women, and what passes for their intellectual elites, discuss, or even think, about economic problems the only tools they have at their disposal is the pseudo-Marxist vocabulary of those who got their Marxism from Cliff Notes (if that). I think there is only one small French group (on Facebook) that is able to evade this conceptual tyranny. In France, thinking in terms of vaguely socialist terms has ceased to be a choice. It’s now a monolithic social and intellectual reality.

I don’t see how even a more determined and more talented political leader than Mr Macron can tell the great mass of the French people: Summer camp is over; everybody go home and learn to make do with less free stuff. Then, re-learn work.

With all this, France is a functioning democracy. The French elected Macron after six years of disastrous “Socialist” Party rule. Perhaps, as has been the case before, the French people -with their historical inability to reform- will be the canary in the mine for everyone else: The big generous state based on taxation is bad for you or for your children. Just ask the French.

No Country for Creative Destruction

Imagine a country whose inhabitants reject every unpleasant byproduct of innovation and competition.

This country would be Frédéric Bastiat’s worst nightmare: in order to avoid the slightest maladies expected to emerge from creative destruction, all their advantages would remain unseen forever.

Nevertheless, that impossibility to acknowledge the unintended favourable consequences of competition is not conditioned by any type of censure, but by a sort of self-imposed moral blindness: the metaphysical belief that “being” is good and “becoming” is bad. A whole people inspired by W. B. Yeats, they want to be gathered into the artifice of eternity.

In this imaginary country, which would deserve a place in “The Universal History of Infamy” by J.L. Borges, people cultivate a curious strain of meritocracy, an Orwellian one: they praise stagnation for its stability and derogate growth because of the stubborn and incorruptible conviction that life in society is a zero-sum game.

Since growth is an unintended consequence of creative destruction, they reason additionally, then there must be no moral merit to be recognised in such dumb luck. On the other hand, stagnation is the unequivocal signal of the good deeds to the unlucky, who otherwise could suffer the obvious lost coming from every innovation.

In this fantastic country, Friedrich Nietzsche and his successors are well read: everybody knows that, in the Eternal Return, the whole chance is played at each throw of the dice. So, they conclude, “if John Rawls asked us to choose between growth or stagnation, we would shout at him: Stagnation!!!”

But the majority of the inhabitants of “Stagnantland” are not the only to blame for their devotion to quietness. The few and exceptional proponents of creative destruction who live in Stagnantland are mostly keen on the second term of the concept. That is why some love to say, from time to time, “we all are stagnationist” – the few contrarians are just Kalki’s devotees.

These imaginary people love to spend their vacations abroad, particularly in a legendary island named “Revolution”. Paradoxically, in Revolution Island the Revolutionary government found a way to avoid any kind of counter-revolutionary innovation. It is not necessary to mention that Revolution Island is, by far, Stagnantlanders’ favourite holiday destination.

They show their photos from their last vacation in Revolution Island and proudly stress: “Look: they left the buildings as they were back in 1950!!! Awesome!!!” If you dare to point out that the picture resembles a city in war, that the 1950 buildings lack of any maintenance or refurbishment, they will not get irritated. They will simply smile at you and reply smugly: “but they are happy!”

Actually, for Stagnantlanders, as for many others, ignorance is bliss, but their governments do not need to resort to such rudimentary devices as censure and spying to prevent people from being informed about the innovations and discoveries occurring in other countries, as Revolutionary Island rulers sadly do. Stagnantlanders simply reject any innovation as an article of faith!

Notwithstanding, they allow to themselves some guilty pleasures: they love to use smartphones brought by ant-smuggling and to watch contemporary foreign films which, despite being realistic, show a dystopian future to them.

As everything is deteriorated, progress is always a going back to an ancient and glorious time. In Stagnantland, things are not created, but restored. As with Parmenides, they do not believe in movement, but if there has to be an arrow of time, you had better point it to the past.

Moreover, Stagnantland is an imaginary country because it does not only lack of duration, but of territory as well. As the matter of fact, no man inhabits Stagnantland, but it is indeed stagnation that inhabits the hearts of Stagnantlanders. That is how, from dusk to dawn, any territory could be fully conquered by the said sympathy for the stagnation.

Nevertheless, if we scrutinise the question with due diligence, we will discover that the stagnation is not an ineluctable future, but our common past. Human beings appeared very much earlier than civilisation. So, all those generations must have been doing something before agriculture, commerce, and institutions.

Before the concept of creative destruction had been formulated by Joseph Schumpeter, it was needed a former conception about how people are conditioned by institutions: Bernard Mandeville pointed out how private vices might turn into public benefits, if politicians arranged the correct set of incentives. The main issue, thus, should be the process of discovery of such institutions.

That is why the said aversion to competition and innovation is hardly a problem of a misguided sense of justice, but mostly a matter of what we could coin as “bounded imagination”: the difficultly of reason to deal with complex phenomena. Don’t you think so, Horatio?

Nightcap

- Reflections on totalitarianism’s greatest critic Daniel Mahoney, City Journal

- Ralph Nader’s weird novel predicted the future Jeff Greenfield, Politico

- Hack gaps and noble lies John Holbo, Crooked Timber

- Social noble lies Bill Rein, NOL

Peer pressure writ large

Part I

We fight for and against not men and things as they are, but for and against the caricatures we make of them.

~ Joseph A. Schumpeter

One hurdle to public discourse that is underrecognized and must be addressed is the simple fact that individuals in the broader population don’t really know what they want. There is often no clear center of self-awareness. Instead, the peer and peer-driven media substitute for personal and communal identity. On the one hand, this situation has existed throughout history without imperiling the human species. On the other hand, this is an era of mass media and peer influence. Therefore, examining role of the peer and its media, specifically social media, is important in a time of societal disruption and discontent.

In the Futurama–Simpsons crossover episode from November 2014, Homer Simpson tries to explain freemium games to the Futurama crew:

Okay, it starts free, right? Then you visit your friend’s game, and he’s got this awesome candy mansion. […] And you’re like, “99 cents?!” You bet I’d like one!” And that’s why I owe Clash of Candies $20,000.

The cartoon aptly summarizes the real-life effect the prevalence of the peer can have. Naturally, there is great comic potential in these situations, and the Simpsons creators capitalized appropriately. Though it is worth adding that the ongoing theme of Homer Simpson possessing a weak character not only made the above quote plausible, it might be a portent to the real problem.

Ruth Davidson of the Scottish Conservative Party wrote an article titled “Ctrl + Alt + Del. Conservatives must reboot capitalism,” in which she argued that the current capitalist arrangement has failed. Concerning the collapse of middle society towns and villages, in the face of growing prosperity in the metro areas she wrote:

How does a teenager living in a pit town with no pit, a steel town with no steel or a factory town where the factory closed its doors a decade ago or more, see capitalism working for them? Is the route for social advancement a degree, student debt, moving to London to spend more than half their take home pay on a room in a shared flat in Zone 6 and half of what’s left commuting to their stagnant-wage job every day; knowing there is precisely zero chance of saving enough to ever own their own front door?

Or is it staying put in a community that feels like it’s being hollowed out from the inside; schoolfriends moving away for work, library and post office closures and a high street marked by the repetitive studding of charity shop, pub, bookies and empty lot – all the while watching Rich Kids of Instagram on Channel 4 and footballers being bought and sold for more than the entire economy of a third world nation on Sky Sports News?

Not a single person familiar with this impossible choice should be surprised by the rise of the populist right and left, of Donald Trump and Jeremy Corbyn, with their simple, stick-it-to-the-broken-system narrative. This is what market failure piled upon social failure piled upon political failure looks like.

If the goal of government is to ensure that everyone has a job and paycheck, Davidson made some very good points. In fairness to her, the cultural attitude today, both in the US and the UK, does indeed tip toward the idea that it is the responsibility of government ministers, such as Davidson, to create magically a world of stable, predictable work and money. What Davidson caught but then also missed is that much of the desire of the people isn’t about money, jobs, or stability, it’s about “social advancement,” to use her own words.

Anyone who thinks that the workers of the old, idealized industrial world were spared non-material social concerns, or arriviste inclinations, is deluded about the course of social history. Nor, are such concerns a purely feminine pursuit, as the Victorians liked to think, supported in their belief by the works of authors such as Jane Austen, Elizabeth Gaskell, and George Eliot (nom de plume of Mary Ann Evans); William Faulkner, Sinclair Lewis, F. Scott Fitzgerald, and, to a lesser extent, Ernest Hemmingway all made careers out of chronicling male social climbing. There is probably something significant about the fact that the second set of authors were all between-the-Wars Americans, but that will have to be set aside for now.

As Polly Mackenzie of the UK think tank Demos wrote, weighing in on the concept of the “working class identity crisis,”

If you’re one of those people who gets a bit misty eyed about the jobs of the past, how fantastic they were, and how they’ll never be replaced, I can hear you scoffing at the notion that putting stuff in boxes [discussion centered on Amazon as the major employer for the low-skilled, under-educated] could ever be meaningful. Those who hark back to the pit villages and steel towns that gave working men a sense of pride and identity will tell me that putting stuff in boxes isn’t ‘man’s work.’

But those people are wrong about where meaning comes from in the workplace. True, some jobs are meaningful because of the direct impact they have in the world – some people save lives, educate children or create works of art. But there’s no such direct meaning in bashing coal off a rock face. Mining is grueling, physical labour, but if that were enough to create meaning then the warehouse jobs could match it, exhausted limb for exhausted limb.

To borrow the title of Gregg Easterbrook’s book, this is The Progress Paradox: everyone is better off but no one is happier. Mackenzie grasped that societal breakdown isn’t about actual jobs; as she also pointed out, none of the “disenfranchised” workers really want to go back to jobs that cost them health and limbs, and the social respect that they claim they’ve lost never truly existed – name one time in history when a coal miner held equal status to a professor or an artist.

Continuing on the confusing, conflicting perceptions of what people want, Henry Olsen of the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington, DC, went to Levittown, PA, and interviewed a wide range of locals in an effort to understand the skeleton of populism.

Greg [a local] put it this way: “Trump is telling them ‘it’s OK to be you.’ The rest of culture is telling them ‘it’s not OK to be you.’”

As Greg told me, whether the message is economic – “you have to go to college to succeed” – or cultural “I like to listen to AC/DC; what’s wrong with that?” – Levittowners and people like them have felt the brunt of elite disdain. In voting for Trump, these blue-collar workers were rebelling against the idea that America is no longer for people like them.

“Levittowners just want a good Christmas for their kids and to go to Jersey Shore for a couple of weeks. They want some acknowledgement that is OK,” Anthony [another local] said. Trump gives them that, and they are willing to overlook nearly everything in exchange.

In conclusion, Olsen wrote:

Rather than viewing global blue-collar discontent through an economic lens, we ought to be looking at populist-backing voters more as people like us, holding similarly cherished identities and hopes. And maybe if we did that, we might all be a bit better off.

It is important to note that according to Olsen, the majority of the local population held Bernie Sanders in equal esteem to Donald Trump. In a broad sense, Olsen’s comments and interviewees echo Davidson and Mackenzie: The good life, rather than simply money, is the fuel behind the average person. The dissonance is that “the good life” varies wildly by perception, not to mention goals.

Consider, for example, the statements uttered by Olsen’s source Greg regarding perceived attitudes on education, economics, and culture. Immediately, it is doubtful that anyone in wider society gives a hoot about any individual’s taste in rock music. In fact, it is more probable that Greg would find the noise issuing from average college dorms and frat houses to be quite recognizable. As a claim for difference and despite, popular culture is a non-starter.

On the success and career side, while the attitude Greg identified certainly exists, it is important to remember that it is the concoction of Americans by and for themselves. The “college-or-nothing” idea is a creation of the peer. The vocational and technical schools which benefited people like Greg didn’t spontaneously close in the decades after World War II; they closed because the market dried up (let’s ignore any correlation to the draft for now) as everyone, flush with post-War prosperity, raced into colleges and universities, regardless of quality or level of preparation. Even now, there are plenty of viable alternatives to obtain skills and commensurate financial independence for the less scholastically inclined. For someone to claim the college-success paradigm as a source of socio-cultural disenfranchisement suggests an ultimate conformity to the pressures of the peer through blind acceptance of a narrow definition of success. The number of fields where it is absolutely true that a person must attend college to succeed are quite few, require specific talents, and are highly specialized. It is not an organic thought for a person with average aspirations and expectations to compare himself to someone in one of these professional areas. Such a comparison only occurs through contact with and shaping of perception by a peer or group of peers.

But, one might argue, how is this possible if the Gregs of the world live their entire lives in circles of people with similar backgrounds and information levels? The answer is through images and the media of imagery. Particularly influential are television and social platforms, such as Instagram, largely because of their capacity to shape perception.

Part II

This photo is titled “Toffs and Toughs,” taken by photographer Jimmy Sime in London in 1937, and it shows two English public (private for Americans) schoolboys waiting for their parents to come pick them up. The photo has two stories, the actual story, and the one built around it by malcontents. The day after Sime took the photo, the leftist and class-warfare fomenting News Chronicle, which later merged into the modern tabloid Daily Mail, published it underneath the headline “Every Picture Tells A Story,” but then declined to clarify the photo at all, beyond misidentifying the two boys in morning dress as Etonians attending the Eton-Harrow cricket match. Almost simultaneously, American Life magazine picked up the photo and published it with further misidentifications and lack of clarification. The message was clear: the elites ignore or turn their back on the underprivileged and working-class.

The real story of the two “elite princelings” was very different. Both boys, students at Harrow, came from solidly middle-class backgrounds; the only trait that might be interpreted as “elite” about them was that their fathers were Harrovians. The younger boy Peter Wagner (on the far left) came from a family of immigrant tradesmen who had bootstrapped their way up the ladder. By 1937, the Wagners had settled into being a family of scientists and stockbrokers, comfortable, respectable, conventional. Peter served honorably during World War II and then took over his family’s business. The older boy Timmy Dyson (center) came from a professional military family, great of name but lacking means. Born into decidedly ordinary circumstances, he spent his childhood as an army brat. His parents only afforded Harrow because he was an only child. He died suddenly a few months after Sime took the infamous photograph.

Of the three “poor” boys, their realities were also much different from the one implied by the photo. None of them was a street urchin. Since they were playing hooky from school the day of the photo, one can extrapolate that they came from families with sufficient means to keep teenage boys enrolled in school despite living in Depression-era London. The two smaller boys, flanking the tall one, both became successful businessmen, while the taller boy became a civil servant. The three never forgave the media for casting them in the role of impoverished victims, arguing that they all had much richer lives than the photograph showed. Literally richer in the case of the two small boys, who post-War reportedly lived at a level of luxury unknown to “elite” Timmy Dyson.

“Toffs and Toughs” is an interesting study of imagery and the myths and perceptions that it can create and perpetuate. It is not an accident that Ruth Davidson, when discussing the modern young person’s alienation from capitalism, wrote, “all the while watching Rich Kids of Instagram on Channel 4 and footballers being bought and sold for more than the entire economy of a third world nation on Sky Sports News.” These are highly visual media which are also highly ersatz, shaped into the appearance of a cohesive whole through skillful editing.

Sports stars (and musicians, dancers, and artists) are terrible for comparison because becoming one requires herculean efforts and hours of practice. An extension of the 10,000-hour rule is: if someone isn’t willing to put in 10,000 hours to master a skill, he has no right to engage in envious nattering. Rich Kids of Instagram is a British reality TV show that spun off of an eponymous Tumblr thread wherein the purported Instagram photos of the superrich are collected. If one examines the pictures with a critical eye, it becomes apparent that the majority are staged – anyone standing on a pier can take a selfie with a docked yacht; it doesn’t mean that he owns the boat.

In the fourth episode, “From Cradle to Grave,” of Milton Friedman’s Free to Choose, 1980 original, at 32:27, Helen Bohen O’Brian, then Secretary of Welfare for Pennsylvania, astutely observed that people estimated their quality of life based on the people around them. What visual media has done is to bring people like the exhibitionists of Rich Kids of Instagram into people’s lives and present them as if they are in some manner the viewer’s peers. It is as divisive and dishonest as claiming that “Toffs and Toughs” told a “story.” If one considers that Guardian columnist Marina Hyde outed the TV show by revealing that a “rich kid” was not particularly rich, was a former tenant of Hyde’s family, and the place portrayed as the reality starlet’s house was their own property, into which the TV crew had unknowingly broken and entered, the deception is exactly on par with the 1937 one. It is all a pitiful lie, but one which, as Davidson spotted, the vast majority of people see and envy as truth.

In closing, there is one last example to consider. Marc Stuart Dreier, currently in prison for fraud, is an ex-lawyer whose scams were eclipsed only by those of Bernie Madoff. In an interview for the BBC documentary Unraveled, Dreier explained that he wasn’t motivated by greed or desire for the “rich life,” no, he wanted to be someone who socialized with golf and football stars. At the start, he was the embodiment of the American dream – son of an immigrant goes to Yale and Harvard Law – but then he discovered that law was not his métier. He neither enjoyed it, nor was he good at it. Unable to succeed through honest means, he turned to fraud. He wanted to be successful, not for its own sake but for the peer group he hoped to join. The documentary shows repeatedly snippets of Dreier in the guise of lawyer-philanthropist glad-handing footballers and playing with famous golfers, always with cameras there to catch every move. The goal was the visuals, not the reality.

In a battle of the mythic caricatures of Joseph A. Schumpeter, the victim is going to be liberty and responsibility. Today, Schumpeter’s words are truer than ever. Everyone has caricatured everyone else. And at the same time, everyone imagines himself on stage with his peers as the audience. There is no doubt that social media and technology have exacerbated the problem of imagery and the peer – fictional Homer Simpson and his candy mansion and Rich Kids of Instagram – but it is delusional to pretend that it didn’t exist before apps and smart phones. Blaming capitalism for the discontent caused by voyeurism and false expectations is both a logical non sequitur and a very serious peril for liberty. For the sake of preserving freedom, it is important to ask, to demand even, by what metric are the disaffected judging their lives. If it is by the peer, as Bohan O’Brian argued, then it is not a valid metric and should be treated as such.

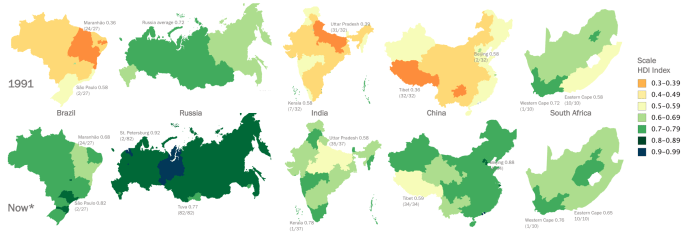

Eye Candy: The HDI of BRICS

Phew, that’s a lot of acronyms. But this is a great map:

Orange and yellow is bad, green and blue is good. HDI stands for “Human Development Index,” which is a measurement that’s not nearly as good, in my opinion, for understanding how wealthy and happy a population is. Nevertheless, HDI is still one of the better measurements (Top 5, again in my opinion) out there. Here’s the wiki on HDI.

The maps are colored according to “subunits,” or provinces (which are like American states, such as Nebraska).

Brazil, India, and South Africa are multi-party democracies, while the other two are not. So what do all five have in common?

Nightcap

- African soldiers (excellent film review) Jeremy Harding, London Review of Books

- Not born in the USA Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Iraq’s Kurds versus Turkey’s Kurds Mahmut Bozarslan, Al-Monitor

- Branko Milanovic’s confusion on inequality David Henderson, EconLog

A Brazilian view on the French Protests

Paris has been taken by a great number of protesters complaining about (yet another) tax, this time on fuel and with the justification of “combating climate change”.

Five years ago, in 2013, several cities in Brazil (Rio de Janeiro among them) were taken by protesters. They were initially complaining about a rise in the bus tariffs. A small rise, if examined by itself, but apparently the last drop among a number of reasons to be discontent.

The Brazilian protests of 2013 were very ironic. Lula da Silva, a socialist, was elected president in 2002. He was reelected four years later, despite major indications that he was involved in corruption scandals. Lula left office very popular, actually, so popular that he was able to make a successor, Dilma Rousseff, elected president in 2012. It was during Dilma’s presidency that the protests took place. They were initially led by far-left groups who demanded free public transportation. So here is the irony: a far-left group, with a far-left demand (free public transportation), was protesting against a (not so far) left government. The situation became even more ironic because millions of Brazilians, who didn’t identify as socialists, also went to the protests, not because they wanted free public transportation (most people are intelligent enough to understand, even if instinctively, that such a thing cannot exist), but because they were fed up with the socialists government at one point or another.

The lesson is: “The problem with socialism is that you eventually run out of other people’s money.” The 2013 protests culminated this year, with Bolsonaro’s election. Mises observed very acutely that socialism simply cannot work. What he observed on paper, reality has confirmed again and again. France is just the latest example.