- The Statue of Liberty is a deeply sinister icon Stephen Bayley, Spectator

- From socialist to left-liberal to neoconservative hawk David Mikics, Literary Review

- Populism in Europe: democracy is to blame, so what is to be done? Philip Manow, Eurozine

- When Medicaid expands, more people vote Margot Sanger-Katz, the Upshot

voting

Legal Immigration Into the United States (Part 16): Toward a One-Party System?

There exists a prospect that continued immigration of the same form as today’s immigration could provide the Democratic Party with an eternal national majority. The US could thus become a de facto one-party state from the simple interplay of demographic forces, including immigration. There are three potential solutions to this problem, the first of which is seldom publicly discussed, for some reason. As the European Union has been showing for thirty years or so, residence in a particular country should not necessarily imply citizenship, the exercise of political rights, in the same country. Ten of thousands of Germans live permanently in France and in Spain. They vote in Germany. (In July 2018, a German woman, thus a citizen of the European Union, who had lived and worked in France for 25 years, and with a French citizen son, was denied French citizenship!) This arrangement, separating residency from citizenship, seems to pose no obvious problem in Europe. (Nikiforov and I discussed this solution in our article in the Independent Review.)

Curiously, in the current narrative, there are no loud GOP voices proposing a compromise with respect to some categories of illegal aliens, I mean, legalization without a path to citizenship. This is puzzling because this is precisely what many illegal aliens says they aspire to. Latin Americans and especially Mexicans frequently say they want to work in the US but would prefer to raise their children back home. (See, for example the good descriptive narrative by Grant Wishard, “A Border Ballad” in the Weekly Standard, 3/9/18.) The simple proposition that easy admission could go with no path to citizenship has the potential to transform immigration to the US, to dry up its illegal branch, and to facilitate border control to a great extent. Yet, there is no apparent attempt to wean immigrants away in this fashion from their Democrat sponsors. The GOP does not seem to have enough initiative to try to reach agreement with immigrant organizations on this basis thus by-passing the Democratic Party. Again, the silence concerning this strategy is puzzling.

In early 2018, President Trump seems to be seeking an answer to the problem of a permanent Democratic takeover by combining the two next solutions. First, would come a reduction in the absolute number allowed to immigrate. Fewer immigrants, fewer Demo voters, obviously. Small government conservatives like me, and rational libertarians also, might simply want to favor reduced immigration as the only sure way to avoid a one-party system even as we believe in the economic and other virtues of immigration.

The second conceptual solution consists in the broad adoption of so-called “merit-based” immigration. There is an unspoken assumption that a merit-based system would produce more middle-class immigrants and, therefore more conservatively oriented immigrants. This assumption is shaky at best. The example of much of the current high-tech Indian immigrants is not encouraging in this respect. More generally, immigrants with college degrees, for example, might turn out more solidly on the left than the current rural, semi-literates from underdeveloped countries who are also avid for upward mobility. The latter also frequently are religious, a condition the Democratic Party is increasingly apt to persecute, at least implicitly. At any rate, reducing the absolute size of immigration carries costs described throughout this essay and merit-based immigration is no panacea, as explained below. I fear that some significant trade-offs between political and other concerns are going to be implemented without real discussion.

[Editor’s note: in case you missed it, here is Part 15]

Should you vote today? Only if you want to.

Today is election day in the United States and everywhere I turn I see “get out the vote” ads. Even on Facebook my feed is filled with people urging others to vote. I am fine with these nudges insofar that they are just that – nudges.

I am concerned when I see claims that voting is one’s duty. I am especially concerned when I see claims that, if you don’t vote, you are allowing the evil [socialists/white men/etc] to govern. These claims concern me because they respectively promote worship of the state and tribalism.

There is more to life than being a politico. If Americans at large sacrificed their other activities in order to become fully informed voter-activists, we would be a boring lot. If you enjoy politics, go vote, but you needn’t feel superior over someone who thinks their time would be better spent playing music or grabbing a beer with friends after work. Life is short and should be spent doing what one enjoys.

Likewise, it is perfectly okay to have an opinion on how government should be run. I, and I imagine most NoL readers, have strong policy preferences. It is however beyond arrogance to believe that an educated person can only believe X and only a mustached villain would believe Y. To be clear, I am not saying that truth is relative.

NIMBYist policies lead to housing shortages, that is a fact. I am in favor of revising zoning regulations and ending parking subsidies to mitigate the problem. I don’t think that the family that owns a detached unit in Santa Monica and opposes denser development is evil though. I understand their hesitance to see their neighborhood changed.

If you wish to vote today, please do so but please don’t act like a snob towards those who do not. Express your policy preferences, but leave your holier than thou attitude at home.

Tldr; play nice.

From the Comments: Bolsonaro is no libertarian (but is he a fascist?)

Barry Stocker outlines the sentiments of many libertarians when he put forth the following argument under Bruno’s “Brazil turns to the Right” post:

Bruno (responding to this and your previous linked post), I’m delighted to be assured that Bolsonaro is not a homophobe, misogynist, a racist or a fascist (an absurdly over used term anyway). However, you offer no evidence to counter the impression that Bolsanaro has leanings in these directions in the Anglophone media, and not just the left-wing media.

Can you deal more precisely with some well known claims about Bolsanoro: he has praised at least one military officer who was a notorious torturer under the last dictatorship, he has praised the dictatorship. I’ve just checked your previous contributions on Brazilian politics and you seem to be in favour of the dictatorship as a agent of struggle against Marxism. I agree that marxism is a bad thing, but it’s not clear to me that means supporting rightist dictatorship.

You say that Bolsanaro understands the need for ‘order’ in Brazilian society. I’m sure we can all agree that Brazil would benefit from more rule of law, but calling for ‘order’ has a rather unpleasant ring to it. The ‘party of order’ has rarely been good for liberty. Can you identify some restrictions on liberty in Brazil that Bolsanaro would remove? Don’t you think there is the slightest risk his attitude to ‘order’ might lead the police to act with more violence? Do you deny that the police sometimes act with excessive violence in Brazil? Do you have any expectation that Bolsanaro will do anything to resolve this or the evident failings of the judicial system?

Do you deny that Bolsanaro said he would prefer his son to be gay rather than die? Don’t you think this gives gays good reason to fear Bolsanaro? I have had a message from a gay American friend who says he is afraid of what will happen and may have to flee the country? Do you understand and care why he is afraid? Do you have any words I can pass onto my friend to reassure him? Preferably not angry words about Gramsci, ‘cultural Marxism’ and ‘gender theory’. Could you actually explain what this ‘gender theory’ in schools is that it i so terrible and apparently justifies Bolsanaro’s crude language? Do you deny that he said a congress woman was too ugly to rape? Can you explain how someone can be fit to hold the highest office in Brazil who makes such a comment?

It’s nice of course that Bolsanaro says now he is favour of free market economics, but isn’t he now back pedalling on this and promising to preserve PT ‘reforms’? Exactly what free market policies do you expect him to introduce and what do you think about the rowing back even before he is in office? Could you say more about which parties and personalities represent classical liberalism now in Congress? If Lula and other leftist politicians (who of course I don’t support at all) have used worse language than Bolsonaro, could you please give examples?

On more theoretical matters

‘Cultural marxism’ to my mind is not an excuse for Bolsanaro’s words and behaviour, or what I know about them. Your account of cultural Marxism anyway strikes me as fuzzy. I very much doubt that Gramsci would recognise himself amongst current ‘cultural Marxists’ and the topics that concern them. I can assure you that a lot of people labelled ‘cultural Marxists’ would not recognise themselves as Marxist or as followers of Marcuse or Gramsci.

The politics of Michel Foucault are a rather complicated and controversial matter but lumping him with some Marxist bloc is hopeless. This isn’t the place to say much about Foucault, but try reading say: *Fearless Speech*, *Society Must Be Defended*, or *Birth of Biopolitics* then see if you think that Foucault belongs with some Marxist or cultural Marxist bloc. The claim that relativism about truth is something to do with Marxism and the anti-liberal left is absurd, all kinds of people with all kinds of politics have had all kinds of views about the status of truth over history. Jürgen Habermas who is an Enlightenment universalist is an influence on the intellectual left, as is Noam Chomsky, a belief in innate knowledge in the form of the universal grammar of languages and associated logical capacity.

Conservatism has often resorted to relativism about the unique values of different countries. Do you think the ancient Sceptics and Sophists have something to do with cultural Marxism? You are referring to these phenomena in a series of familiar talking points from conservative pundits which do not make sense when applied to rather disparate people with different kinds of leftism, of course I have criticisms of them but different kinds of criticisms respecting differences between groups, in which I try to understand their arguments and recognise that sometimes they have arguments worth taking seriously, not a series of angry talking points.

I look forward to being educated by your reply. Please do give us detail and write at length. I write at length, so does Jacques, so there is no reason why you should not.

Again, Barry’s arguments are a good indication of how many in the libertarian movement, worldwide, view Bolsonaro (and others like him, such as Trump), but, while I eagerly await Bruno’s thoughts on Barry’s questions, I have my own to add:

Bolosonaro got 55% of the vote in Brazil. How long can leftists continue to keep calling him a “fascist” or on the “far-right” of the Brazilian political spectrum, especially given Brazil’s cultural and intellectual diversity? Leftists are, by and large, liars. They lie to themselves and to others, and maybe Bruno’s excitement over Bolsonaro’s popularity has more to do with the cultural rebuke of leftist politics in Brazil than to Bolsonaro himself; he’s well-aware, after all, that Brazil’s problems run deeper than socialism.

Bolsonaro’s vulgar, dangerous language might be entertaining, and Brazil’s rebuke of socialist politics is surely encouraging, but it can be easy to “take your eye off the ball,” as we say in the States. Brazil has a long way to go, especially if, like me, you think Brazilians have elected yet another father figure rather than a president tasked with running the executive branch of the federal government.

Brazil’s Turn to the Right

Last elections in Brazil are not yet over. Brazilians will go back to the polls before the end of this month to decide who will be the country’s next president. But few doubt that Brazil’s next president will be Jair Messias Bolsonaro.

No matter what you read in mainstream media, Bolsonaro is not homophobic. He is not racist. He is not misogynist. And certainly, he is not a fascist. If he is any of these things, he hides pretty well. His language can certainly be very crude, and he can be very direct in his speech. Maybe that is exactly why he is being elected. Brazilians are tired of politicians who don’t speak their minds. With Bolsonaro, what you see is what you get.

And what do you get? Bolsonaro is not strong on any ideology. He is a self-professed Christian (somewhere between a Roman Catholic and an Evangelical), a Patriot and a family man. Because of his patriotism, for many years he believed in protectionism and developmentalism, but it seems more and more that he left these things in the past. Bolsonaro is inclined to defend free-market policies.

Alongside Bolsonaro, a very right-wing congress has been elected. For the first time in many decades, Brazil has many representatives who are ideologically classical liberals or conservatives. This is even better than having Bolsonaro as president. Meanwhile, the leftist parties (especially the Workers Party of Lula da Silva) lost quite some terrain.

If Bolsonaro and this Congress make a mildly good govern, the left will be in serious trouble in Brazil. Brazil is still a very poor country where people, for the most part, don’t vote ideologically. They vote in those who can bring development to their lives. That’s how Lula da Silva got reelected and was able to elect a successor, even with major corruption scandals surrounding him and his party.

The wind of change in Brazil is better than anything I could expect.

Nightcap

- Isolated in Africa, Chinese workers get religion en masse Yuan & Huang, Global Times

- Explaining Hazony’s nationalism Arnold Kling, askblog

- A prison journalist doing work — from the inside Daniel Gross, Literary Hub

- Character-based voting and the policy of truth Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

Liberalism, Democracy, and Polarization

Is polarization a threat to democracy and what is the liberal position on this?

As I pointed out in Degrees of Freedom, most liberals have a preference for democracy. Modern-day democracy – with universal suffrage, a representative parliament, and elected officials – has been developed over the course of the twentieth century. The idea has its roots in antiquity, the Italian city states of the Renaissance, and several forms for shared political decision-making in Scandinavia, Switzerland, the Netherlands, and England. Democracy is not a liberal “invention,” but the term ‘liberal democracy’ has taken firm root. This is true because modern democracy is based on liberal ideas, such as the principle of “one man, one vote,” protection of the classical rights of man, peaceful change of political leadership, and other rules that characterize the constitutional state.

Remarkably, the majority of liberals embraced the idea of democracy only late in the nineteenth century. They also saw dangers of majority decision making to individual liberty, as Alexis de Tocqueville famously pointed out in Democracy in America. Still, to liberals democracy is better than alternatives, such as autocracy or absolute monarchy. This is not unlike Sir Winston Churchill’s quip “it has been said that democracy is the worst form of government, except all the others that have been tried.” Yet there is a bit more to it for liberals. It is has proven to be a method that provides a decent, if imperfect, guarantee for the protection of individual freedom and the peaceful change of government.

Of course there is ample room for discussion inside and beyond academia about numerous different issues, such as the proper rules of democracy, different forms of democracy, the role of constitutions in democracy, whether referenda are a threat or a useful addition to representative democratic government, the roles of parties, party systems, and political leaders, et cetera. These are not the topic here.

In the context of the election of President Trump, but also before that, both inside and outside the US, there is a wide debate on the alleged polarization in society. By this is meant the hardening of standpoints of (often) two large opposing groups in society, who do not want to cooperate to solve the issues of the day, but instead do everything they can to oppose the other side. Consensus seeking is a swear word for those polarized groups, and a sign of weakness.

There appears less consensus on a number of issues now than in the past. Yet this is a questionable assumption. In the US it has been going on for a long time now, certainly in the ethical and immaterial area, think about abortion, the role of the church in society, or freedom of speech of radical groups. Yet most (Western) societies have been polarized in the past along other lines, like the socialist-liberal divide, the liberalization of societies in the 1960s and 1970s, or more recent debates about Islam and integration. Current commentators claim something radically different is going on today. But I doubt it, it seems just a lack of historical awareness on their side. I can’t wait for some decent academic research into this, including historical comparisons.

As a side note: a different but far more problematic example of polarization is gerrymandering (changing the borders of legislative districts to favour a certain party). This has been going on for decades and can be seen as using legal procedures to rob people not of their actual voting rights, but of their meaningful voting rights. Curiously, this does not figure prominently in the current debates…

The (classical) liberal position on polarization is simple. Fighting for, or opposing a certain viewpoint, is just a matter of individual right to free speech. This also includes using law and legislation, existing procedures, et cetera. The most important thing is that in the act of polarizing there cannot be a threat to another person’s individual liberty, including the classical rights to life, free speech, and free association, among others. Of course, not all is black and white, but on the whole, if these rules are respected I fail to see how polarization is threat to democracy, or why polarization cannot be aligned with liberalism.

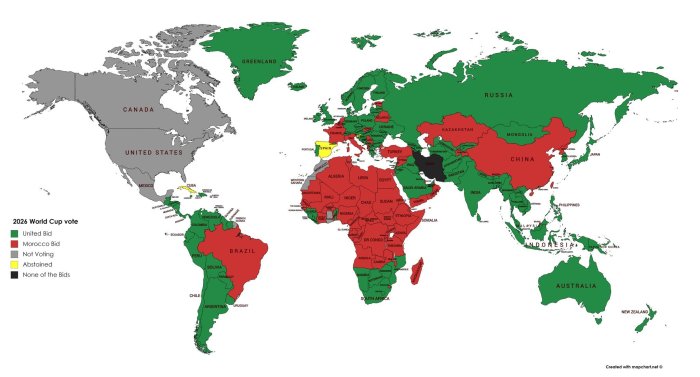

Eye Candy: 2026 World Cup votes, by country

My only question is why did 3 countries that could easily (and have, in the past) host the World Cup on their own gang together? Mexico, Canada, and the United States are wealthy countries. Why gang up?

My guess is that wealthier countries are going to have to do a lot more cooperating if they want to host world-level events from now on, due to the fact that the selection process for these types of events has become democratized. Economist Branko Milanovic has a thoughtful piece on FIFA (the governing body for world-level soccer events) and corruption that ties in to all of this.

Nightcap

- An election day parable Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Unrevolutionary bastardy Hannah Farber, The Junto

- Voting for a lesser evil Ilya Somin, Volokh Conspiracy

- Max Weber’s ‘spirit’ of capitalism Peter Ghosh, Aeon

Nightcap

- Does the recognition lag give the Fed an alibi for 2008? Scott Sumner, EconLog

- Dudley’s Defense of the Fed’s Floor System George Selgin, Alt-M

- Progress in economics Chris Dillow, Stumbling and Mumbling

- Moral grandstanding and character-based voting Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

Are voting ages still democratic?

Rather par for the course, our current gun debate, initiated after the school shooting in Parkland, has been dominated by children — only this time, literally.

I’m using “children” only in the sense that they are not legally adults, hovering just under the age of eighteen. They are not children in a sense of being necessarily mentally underdeveloped, or necessarily inexperienced, or even very young. They are, from a semantics standpoint, still teenagers, but they are not necessarily short-sighted or reckless or uneducated.

Our category “children” is somewhat fuzzy. And so are our judgments about their political participation. For instance, we consider ourselves, roughly, a democracy, but we do not let children vote. Is restricting children from voting still democratic?

With this new group of Marjory Stoneman Douglas high school students organizing for political change (rapidly accelerated to the upper echelons of media coverage and interviews), there has been widespread discussion about letting children vote. A lot of this is so much motivated reasoning: extending suffrage to the younger demographic would counter the current proliferation of older folks, who often vote on the opposite side of the aisle for different values. Young people tend to be more progressive; change the demographics, change the regime. Yet the conversation clearly need not be partisan, since there exist Republican- and Democrat-minded children, and suffrage doesn’t discriminate. (Moreover, conservative religious groups that favor large families, like Mormons, could simply start pumping out more kids to compete.)

A plethora of arguments exist that do propose pushing the voting age lower — 13, and quite a bit for 16 (ex. Jason Brennan) — and avoid partisanship. My gripe about these arguments is that, in acknowledging the logic or utility of a lowered voting age, they fail to validate a voting age at all. Which is not to say that there should not be a voting age in place (I am unconvinced in either direction); it’s just to say that we might want to start thinking of ourselves as rather undemocratic so long as we have one.

An interesting thing to observe when looking at suffrage for children is that Americans do not consider a voting age incompatible with democracy. If Americans do not think of America as a democracy, it is because our office of the President is not directly elected by majority vote (or they think of it as an oligarchy or something); it is not undemocratic just because children cannot vote. The fact that we deny under-eighteen year olds the vote does not even cross their minds when criticizing what many see as an unequal political playing field. For instance, in eminent political scientist Robert Dahl’s work How Democratic is the American Constitution? the loci of criticism are primarily on the electoral college and bicameral legislature. In popular parlance these are considered undemocratic, conflicting with the equal representation of voters.

Dahl notes that systems with unequal representation contrast to the principle of “one person, one vote.” Those with suffrage have one or more votes (as in nineteenth-century Prussia where voters were classified by their property taxes) while those without have less than one. Beginning his attack on the Senate, he states “As the American democratic credo continued episodically to exert its effects on political life, the most blatant forms of unequal representation were in due time rejected. Yet, one monumental though largely unnoticed form of unequal representation continues today and may well continue indefinitely. This results from the famous Connecticut Compromise that guarantees two senators from each state” (p. 48).

I quote Dahl because his book is zealously committed to majoritarian rule, rejecting Toqueville’s qualms about the tyranny of the majority. Indeed, Dahl says he believes “that the legitimacy of the Constitution ought to derive solely from its utility as an instrument of democratic government” (39). And yet, in the middle of criticizing undemocratic American federal law, the voting age and status of children are not once brought up. These factors appear to be invisible. In our ordinary life, when the voting age is brought up, it is nearly always in juxtaposition to other laws, e.g., “We let eighteen year olds vote and smoke, but they have to be 21 to buy a beer,” or, on the topic of gun control, “If you can serve in the military at 18, and you can vote at 18, then what is the problem, exactly, with buying a gun?”

What is the explanation for this? We include the march for democracy as one progressive aspect of modernity. We see ourselves as more democratic than our origin story, having extended suffrage to non-whites, women and people without property. We see America under the Constitution as a more developed rule-of-the-people than Athens under Cleisthenes. So, we admit to degrees of political democracy — have we really reached the end of the road? Isn’t it more accurate that we are but one law away from its full realization? And of course, even if we are more of a representative republic, this is still under the banner of democracy — we still think of ourselves as abiding by “one person, one vote” (Dahl, 179-183).

In response, it is said that children are not properly citizens. This allows us to consider ourselves democratic, even while restricting direct political power from a huge subset of the population while inflicting our laws on them.

This line of thought doesn’t cut it. The arguments for children as non- or only partial-citizens are riddled with imprecisely-targeted elitism. “Children can be brainwashed. Children do not understand their own best interests. Children are uninterested in politics. Children are not informed enough. Children are not rational. Children are not smart enough to make decisions that affect the entire planet.”

Although these all might apply, on the average, to some age group — one which is much younger than seventeen, I would think — they also apply to all sorts of individuals distributed throughout every age. A man gets into a car wreck and severely damages his frontal lobe. In most states there is no law prohibiting him from dropping a name in the ballot, even though his judgment is dramatically impaired, perhaps analogous to an infant. A nomad, who eschews modern industrial living for the happy life of travel and pleasure, is allowed to vote in his country of citizenship — even though his knowledge of political life may be no greater than someone from the 16th century. Similarly, adults can be brainwashed, adults can be stupid, adults can be totally clueless about which means will lead to the satisfaction of their preferred ends.

I venture that all Americans do not want uninformed, short-sighted, dumb, or brainwashable people voting, but they will not admit to it on their own. Children are a proxy group to try to limit the amount of these people that are allowed in on our political process. And is banning people based on any of these criteria compatible with democracy and equality?

Preventing “stupid” people from voting is subjective and elitist; preventing “brainwashable” people from voting is arbitrary; preventing “short-sighted” people from voting is subjective and elitist, and the same for “uninformed” people. We come to the category of persons with severe mental handicaps, be their brain underdeveloped from the normal process of youth, or injury, or various congenital neurodiversities. Regrettably, at first glance it seems reasonable to prevent people with severe mental defects from voting. Because, it is thought, they really can’t know their interests, and if they are to have a voting right, it should be placed in a benefactor who is familiar with their genuine interests. But now, this still feels like elitism, and it doesn’t even touch on the problem of how to gauge this mental defect — it seems all too easy for tests to impose a sort of subjective bias.

Indeed, there is evidence that this is what happens. Laws which assign voting rights to guardians are too crude to discriminate between mental disabilities which prevent voting and other miscellaneous mental problems, and make it overly burdensome to exercise voting rights even if one is competent. It is hard to see how disenfranchising populations can be done on objective grounds. If we extended suffrage from its initial minority group to all other human beings above the age of eighteen, the fact that we prolong extending it to children is only a function of elitism, and consequently it is undemocratic.

To clarify, I don’t think it is “ageist” to oppose extending the vote to children, in the way that it is sexist to restrict the vote for women. Just because the categories are blurry doesn’t mean there aren’t substantial differences, on average, between children and adults. But our reasoning is crude. We are not anti-children’s suffrage because of the category “children,” but because of the collective disjunction of characteristics we associate underneath this umbrella. It seems like Americans would just as easily disenfranchise even larger portions of the population, were we able to pass it off as democratic in the way that it has been normalized for children.

Further, it is not impossible to extend absolute suffrage. Children so young that they literally cannot vote — infants — could have their new voting rights bestowed upon their caretakers, since insofar as infants have interests, they almost certainly align with their daily providers. This results in parents having an additional vote per child which transfers to their children whenever they request them in court. (Again, I’m not endorsing this policy, just pointing out that it is possible.) The undemocratic and elitist nature of a voting age cannot be dismissed on the grounds that universal suffrage is “impossible.”

It is still perfectly fine to say “Well, I don’t want the boobgeoisie voting about what I can do anyway, so a fortiori I oppose children’s suffrage,” because this argument asserts some autocracy anyway (so long as we assume voting as an institutional background). The point is that the reason Americans oppose enfranchising children is because of elitism, and that the disenfranchising of children is undemocratic.

In How Democratic is the American Constitution? the closest Robert Dahl gets to discussing children is adding the Twenty-Six Amendment to the march for democratic progress, stating that lowering the voting age to eighteen made our electorate more inclusive (p. 28). I fail to see why lowering it even further would not also qualify as making us more inclusive.

In conclusion, our system is not democratic at all,

Because a person’s a person no matter how small.

Public choice and market failure: Jeffrey Friedman on Nancy MacLean

Jeffrey Friedman has a well-argued piece on interpreting public choice in the wake of Nancy MacLean’s conspiratorial critique of one of its founding theorists, James Buchanan. While agreeing that MacLean is implausibly uncharitable in her interpretation of Buchanan, Friedman suggests that many of Buchanan’s defenders are themselves in an untenable position. This is because public choice allows theorists to make uncharitable assumptions about political actors that they have never met or observed. In this sense, MacLean is simply imputing her preferred own set of bad motives onto her political opponents. What is sauce for the goose is good for the gander.

I think Friedman’s arguments are a valid critique of the way that public choice is sometimes deployed in popular discourse. A lot of libertarian commentary assumes that those seeking political power are uniquely bad people, always having self-interest and self-aggrandisement as their true aim. Given that this anti-politics message is associated with getting worse political leaders who are becoming progressively less friendly to individual liberty, this approach to characterising politicians seems counterproductive. However, I don’t think Friedman’s position is such a good fit for Buchanan himself or most of those working in the scholarly public choice tradition.

“Fuck Your Vote!”

That’s what I have been hearing ever since the morning after the presidential election. That what I keep hearing on most cable television and on National Public Radio. That’s what I see in most of what I read, and that’s what I am told is being published in the liberal print media I stopped reading long ago. That’s also what I find when I go slumming in left-wing sectors of Facebook.

No one has actually told me directly, in those exact words, “Fuck your vote,” not yet, but that’s what the ceaseless hounding of Pres. Trump means: My vote for him ought to be ignored; it can’t possibly count. If you had not had any news for six months, you would think that there had been a coup in the United States; that a horrid, caricature capitalist had taken over the country by stealth and by force, both. You would guess that the intellectually and morally live segments of American society were resisting a brutal takeover as best as they could. You would not guess there had been a hotly disputed election, fielding 16 viable candidates on one side.

A grass-root movement with a strategy

The verbal lynching to which Pres. Trump is subjected on a 24-hr cycle is not a conspiracy. There is no secrecy to it. It’s all overboard. It’s a regrouping of the political establishment, of the 90% leftist media, of the 90% leftist academia, of the vast tribe of government bureaucrats, of the many others who live off tax revenue, of the labor unions leaders, of the teachers’ unions, especially. So, after a fashion, it’s a genuine grass root movement. It’s a grass root movement of the well-bred and of the semi-educated who spend all their time – always did – feeling “appalled.”

It’s not a conspiracy but it’s a deliberate plot. It has a strategy: Hound him until he loses his cool completely. Harass him to the point where he cannot govern at all. At worst, we can keep him so busy his intended policies kind of vanish. The Santa Cruz AM station where I had a political show for three years has its own well-known, semi-official leftist caller, “Billy.” Billy thinks he is well informed and a genuine, deep-thinking intellectual because he is leisurely. In fact, he does not work for a living; he lives off his rich wife instead. (I would not make this up.) He called the station about two weeks before this writing to sound off on one thing or another that the president had done or said. Then, he declared straightforwardly, “We are hounding him out of office,” and also, with commendable clarity, “It’s a slow coup.” I would not have dared used these words in my conservative (“libéral” en Français) polemical writing, too provocative, possibly exaggerated.

Or take this short, childishly coded message I picked out from from an ordinary left-liberal’s Facebook page:

“47 could end up being Pelosi if we drag it out til 18.”

Translation: the current minority leader in the House could become the next president (the 47th). If we drag what out? For overseas readers and for American readers who went to the beach when the US Constitution was taught in high school: What has to happen before the minority leader of the House of Representatives becomes president outside of a presidential election? The constitutional order of succession if the president dies, in any way of manner, or becomes incapacitated, or is remove from office for any reason is this: Vice-President, Speaker of the House. In the partial elections of 2018, Nancy Pelosi may become Speaker of the House again. She would automatically become president if and only if both President Trump and Vice-President Pence were eliminated. Hence the FB message: Keep up the harassment. Note: Some readers might think I am making this up. I will give the name and FB address of the person from whom this is taken to anyone asking me privately.

What does not revolt me: Donald Trump is a bad person

What is it that makes me angry? Let me begin by telling you what does not make me deeply angry.

First, everyone here and abroad has every right to dislike Mr Trump personally, Trump the man. There is a lot I don’t like about the man myself. He talks too much; he is ignorant of many things; his ignorance does not stand in the way of his having strong opinions about the very same things; he often talks before he thinks; he brags too much; he is too frequently crude. (Actually, I am of two minds about the latter. Official crudeness may be the form that starting to roll back political correctness must take.)

I did not vote for Donald Trump because I loved him but mostly because of the character of the only, single alternative to him at the time of the presidential election. (Keep in mind that Sen. Sanders was not on the ballot. Remember what happened to him?) I had no illusions from day one. I knew that Mr Trump is not at all like suave President Obama, for example, who was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize within barely ten months of taking office.* I voted for Trump also for policy reasons. I thought there was a good chance he would appoint a conservative Supreme Court Justice, as promised. He did, within days. I thought he would deregulate to some extent. He is doing just that. I thought we stood a better chance of having serious tax cuts with him than with the Democratic candidate. I still think so. Tax cuts are the most direct path to vigorous economic growth, I believe. (Shoot me!)

A short digression: As I was writing this cri du coeur, the liberal media were exulting about President Trump’s loss of a few points of general approval. (Actually, it’s about the same as Bill Clinton’s at the same period in their presidencies.) They don’t mention that there is zero evidence that he has lost any ground among those who voted for him, that they feel any voter remorse. Myself, I like him better than I did when I voted for him. He has begun to make America stand up again. He has been a bulwark against several forms of hysteria – including Endofworldism – to a greater extent than I counted on.

What does not revolt me: Opponents trying to stop and sink his program

The second thing to which I do not object in the treatment of President Trump is legislative maneuvering. Democrats and dissident Republicans have every right to block and undermine Mr Trump’s legislative programs, be they tax cuts or “the wall.” (Personally, I want the first ones and think of the second as a silly idea.) The media have every right and sometimes an obligation to support this exercise in checks and balances between executive and legislative that is at the heart of the US constitution. No problem there either. I understand that when you win the presidency, in the American system, that’s all you have got, the presidency. After that, you have to convince Congress to pay for what you want, for what you (conditionally) promised.

What annoys me without revolting me: the courts’ usurpation

The Founding Fathers decided that courts had to be able to curtail or block just about any executive or legislative action. This, to make extra sure that neither branch of government could ever create unconstitutional law. This, to avoid the tyranny of the majority. It often rankles but that’s how our constitutional democracy works. Accordingly, the third going on that annoys me but that I accept is the several courts’ endeavors to stop the president from taking the measures he thinks necessary to keep the country safe. (I try to distinguish between dislike and a negative judgment of illegitimacy. This distinction is a the heart of the problem about which I am writing.) I accept, for example the decisions of the two or three courts who stopped the presidential executive order banning the admission of peoples from a handful of countries. I accept them, although:

Public opinion and – I think – one court, call it a ban “on Muslims,” even if only 9% of all Muslims worldwide would be affected; although half of those are citizens of a country – Iran – that is the declared enemy of the US and officially a sponsor of terrorism as far as we (Americans) are concerned.** and ***.

I accept it although there is nothing in the Constitution that prevents the executive branch from stopping people entering the US based on their religion.

I accept it although there is no part of the US Constitution that recognizes any rights to foreigners who are neither under American jurisdiction nor at war with the US.

I accept it although there is a statute, a law, that explicitly gives the president the right to ban the entry of anyone for any reason.

I accept these court orders but my acceptance is a testimony to my strong commitment to constitutional democracy.

Now, on to what I object to deeply and irreversibly in the attacks on the president.

Extirpating electoral legitimacy

What really, really disturbs me are the nearly daily attempts at removing, at extirpating the legitimacy of the 2016 presidential election results, the desperate and brutal, unscrupulous attempts to make people believe that Mr Trump is not really president. They make me livid because they are not attacks on Mr Trump but rather, they are attacks on me. They are assaults on my right to exercise my constitutional right to cast my vote and to have it counted. And also the rights of sixty-three million Americans**** who voted as I did. The slow coup against Mr Trump defies reason and it resembles nothing I have seen in fifty years in this country. It does remind me of several historical precedents though. (Look up “March on Rome,” you will be amazed.)

More than the mechanics of democracy is at stake. The principle of government by the consent of the governed itself is under assault, the attack is systematic and unrelenting. When I cast one of approximately sixty-three million votes for Donald Trump, I thought I was choosing the lesser of two evils. That’s nothing new; I don’t remember ever voting in a national election for someone who inspired enthusiasm in me. And perhaps, that’s the way it should be. Enthusiasm about a person may not be even compatible with democracy. Free men and women don’t need saviors and they are leery of leaders, even of leadership itself. Be it as it may, I cast my vote as I did and no one (that’s “no”) has the right to try and nullify it, to cancel it. As I write this self-evident truth, I fear that many of the people still having hysteria about the 2016 Democrats’ failure are not sophisticated enough to understand the difference between opposing the consequences of my vote through accepted, traditional parliamentary and judicial maneuvers on the one hand, and nullifying my vote, on the other hand.

Fascism is neither of the left or of the right. It thrives on moral confusion and on bad logic. Hysteria is its main sustenance.

“The Russians” made them lose everything

The daily assault on the Trump legitimacy changes form almost every day. Right now, it has been focusing for several weeks on alleged Russian intervention in the presidential election.

It matters not to the Trump haters that in 2016 Democrats lost everything they could lose besides the presidential election: governor races, state legislatures, Congress. This swath of defeats seems to me to indicate that the Democratic Party in general was not popular, forget Trump. If “the Russians” had actually handed out the presidency to Mr Trump, there would still be a need to explain the Democrat routs at all other levels. Did “the Russians” also organize the rout, including of county boards of supervisors, and at all other minute local levels?

It does not matter that Mrs Clinton was never made to explain how and why she caused to erase or ditch 30,000 emails belonging to the government, a cynical suppression of evidence if there was ever one.

A considerable work of imagination

Thus far, the mud has been thrown at Mr Trump and at his whole team, at any one who has ever met him perhaps in connection with “Russian” interference in the presidential election. Mud has no shape; it’s amorphous. I don’t know about him but when I suspect someone of something, the something has a shape, at least a rough description. You never say, “I suspect you,” but, “I suspect you of X or of Y.” The Trump accusers have never been able to reach even that primitive level of concreteness. None of them has (yet) been stupid enough to suggest that the Russian secret services hacked or tricked up the voting machines in the hundreds of jurisdictions that would be needed to make a difference. So, what have “the Russians” done, really?

The most tangible thing they have against the Trump campaign to-date is a supposition, a product of the collective imagination, and it need not even involve Trump or his agents at all. What we know is that someone hacked the Democratic National Committee emails. Some contents were leaked by Wikileaks which did not say where it got it from. Wikileaks has friendly links with Russia. It’s possible Russians hackers gave it the info. If this is what happened, here is what we still don’t know:

We don’t know that those imagined Russian hackers worked for Pres. Putin. Entrepreneurial Russian hackers have been dazzling us for twenty years. The DNC email seems to have been poorly protected, anyway. A Putin intervention is superfluous in this story.

Furthermore: Do you remember what Wikileaks disclosed (thanks to “the Russians.”)? It showed that the Democratic establishment engineered, by cheating, the defeat of candidate Sanders in the Democratic primary elections. In my book, the anonymous, perhaps Russian, hackers deserve a medal, an American medal for casting light on dysfunction and plain dishonesty within an American political party. The Congressional Medal of Honor is not out of the question, in my book.

Moreover: The leftist media keep referring to “collusion” between members of the Trump campaign and some unnamed Russians. Sounds sinister, alright. But as the Harvard Law Professor Alan Dershowitz, – a Democrat – pointed out recently, “collusion” is not illegal. It’s what you collude to do (rob a bank) that makes it criminal. Colluding to eat a pizza is not criminal. Mr Trump and his entourage are daily accused -without proof – of having committed acts that are not illegal.

The first Comey testimony

The 06/08/17 open, public Senate Judiciary hearing of dismissed FBI Director Comey was awaited by the left and media, and also by some genteel Republicans, like the Roman plebe awaited the lions’ feasting on the Christians. That hearing was a disappointment too. I am writing here as if I thought every word uttered by Mr Comey were exactly true (100% true) although there is no reason to do so. The hearing showed ex-FBI Director to be a leaky wimp, of shaky integrity caught in corrupt and difficult circumstances, first under Obama with the Clinton Follies, then with the unpredictable Trump presidency. It did showcase a great deal of inappropriate behavior by President Trump. But the hearing did not even begin to point to any illegal behavior on the part of the president, not to a single whiff of illegality. If you don’t trust my legal judgment (although I watch many crime shows on TV), refer again to Democrat and Harvard Law School professor Dershowitz who thinks as I do on this issue. The fact is that hardly anyone, possibly no one, voted for Mr Trump because of the appropriateness of his behavior or of his statements. If anyone was about to do so during the election, the airing by the Clinton campaign of a tape describing Mr Trump’s manual approach to seduction would have cured that illusion.

Next?

Personally, I think there is nothing to investigate. Nevertheless, I hope the Special Counsel (a friend of Comey’s, it turns out) will do his job of investigating the possibility that President Trump did whatever he is supposed to have done with I know not what Russians. There is a chance that merely having a single person in charge – what the left demanded – will reduce the daily din of anti-Trump insults. There is even a possibility that it will allow Pres. Trump to get to work on some more of the projects***** for which I gave him my vote. If the investigation reveals real illegal behavior by Mr Trump, felony-level crimes, I think he should be peaceably removed from office, with Vice-President Pence taking over as required by the US Constitution. Anything else, any other succession would be a form of fascism. Any other scenario of Trump removal turns my attention to the Second Amendment (me and hundreds of thousands of gun-crazy, church going “deplorables.”)

How it will end

I don’t see a reasonable finish to all this unless the president is found guilty of something. When the smoke finally clears, when the investigation of President Trump’s collusion to do whatever with whatever Russians ends, I think there is no chance that the matter will be finally put to rest. If the Special Counsel that liberals clamored for concludes that Mr Trump and his whole entourage never committed any illegal act in connection with the 2016 election, there will still be voices pointing out that an intern on Trump’s campaign once ate Russian caviar on a date, which raises serious questions! Or something.

The undisputed fact, that Mr Trump’s improprieties revolt many who voted for the only real alternative, is not an argument for overthrowing an elected government. They are the same people who tried to elect – directly or indirectly – an old woman apparently in failing health, a lackluster former Secretary of State, at best, a person who campaigned incompetently, a candidate for the highest office who never managed to articulate her vision of government, a person who cheated during the primary election, one who ended up losing against a rank political amateur who spent less than half the money she spent on campaigning. With a large majority of voters guilty of such a poor choice, this country has bigger fish to fry, I would think, than presidential rudeness and/or insensitivity.

Conclusion

Dear Trump–hating fellow citizens: One thing that did not cross my mind when I voted was that should my candidate win – a long shot at the time – there would be a massive, multi-pronged endeavor to make believe that I had not voted, or that I had voted other than the way I voted, or that my vote somehow did not count. I thought I was living in a democracy. I assumed the democracy was lodged not only in the rules we follow to form governments but in the hearts of my fellow-citizens. I assumed that the rules were internalized, that they were part of the moral baggage of everyone including those whose vote countered mine.

If you will not accede to the modest wish that my vote should be honored, why bother with elections at all? They are costly and disruptive, they often disappoint, sometimes more than half of the population, and they provide many opportunities for the expression of deplorable taste. Why not, for example, convene a governing directory selected by an assembly of university professors, of well-bred employees’ union leaders, of Democratic politicians, and of media personalities (excluding Fox, and also Rush Limbaugh, of course), all chaired by the Editor-in-Chief of the New York Times?

* Just because you ask, I will tell you that I am guessing that the silly old men of the Norwegian Nobel Committee actually thought they were giving the Prize to the American left electorate for electing a Negro (“neger,” in Norwegian). It’s also a fact that Mr Obama always looks good in a suit.

** To my overseas readers: It was not Pres. Trump who designated officially Iran as a sponsor of terrorism. It happened several presidential administrations back, many years ago.

*** I wonder if the said executive order would have been acceptable to the courts if President Trump had thrown in say, a Buddhist country or two, and a pair of Catholic countries from South America, for example, like this: ban on admission to the US for citizens of Somalia, Yemen, Laos, Syria, Paraguay, Iran, etc.

**** Note to my overseas readers: That’s 2.8 million fewer than won by candidate Clinton. In the US system the candidate who obtains the largest number of votes cast by citizens (the “popular vote”) does not necessarily win the presidency. We have indirect elections instead. This may seem strange but the fact is that neither big party has ever really tried to change the constitution in this respect. So, after the two Obama victories, no one in the Democratic party said, “We have to change this system to make sure the popular vote prevails.” And if we had a popular vote system, all candidates would have campaigned differently. Mr Trump might have won the popular vote handily, or Mrs Clinton may have won with a margin of ten million votes or more; or the Libertarian Party may have received enough votes to deny either candidate a majority. There are many other possibilities in the world of “what if….”

***** Some of his campaign promises are being fulfilled at a fast clip in spite of the ceaseless persecution to which the president is subjected. The loosening of the regulatory hands of the Federal Government on the economy’s neck, for example, is going well.

We can’t engineer our way out of this

Folks on the left have been getting more interested in science lately (though history tells us that might be something to worry about). They’re right to celebrate the incredible results of scientific progress–but scientific victory isn’t uniform across disciplines.

In some areas (including just about all areas on the cutting edge), scientists disagree with one another.It’s a big, complex world we live in, and we don’t understand it fully. That disagreement doesn’t mean we should discount science entirely, but it does mean we should be careful with it.

Imagine a world where engineers disagreed about the capabilities of their techniques and the strength of the materials they use. Some might be beholden to special interests (which gives me an idea for a public choice version of the Three Little Pigs), others might be dogmatic/superstitious. But even without concerns of systemic issues, we should be hesitant to try to get to the moon. That disagreement should tell us that we aren’t certain enough in our knowledge to make anyone but volunteers put their lives in the hands of those engineers.

Social scientist in particular frequently disagree with each other. Most are trying earnestly to apply the scientific way of thinking to understanding the social world, and it’s worth considering their view points. But applying that knowledge should only be done in a decentralized way. Applying the incredible insights of behavioral economics from the top down is appealing, but it’s probably best to do it piecemeal.

Social engineering and social science are harder than physical engineering and the physical sciences. Part of the problem Western governments face is that they’re trying to engage in social engineering. And politicians are promising them greater degrees of social engineering to improve the well-being of their constituents.

The trouble is two-fold: 1) those social engineering techniques aren’t good enough, even if they’re sometimes appealing. 2) The cost to decision makers of buying snake oil is too low in voting booths.

To my friends who are looking to the government to make things better: whether your hope is for government to help people be better versions of themselves, or to stop bad guys, we should push as much of that policy to the local level as possible. It might be nice if the whole country were more like Berkeley or Salt Lake City, but trying to make it happen at the national level is a recipe for conflict, disorder, and doing more harm than good. Keep policy local.

Summing up: the year of irrationality

Brandon says I’ve got one last chance to write his favorite post of the year. But it’s the end of a long semester and I’m brain dead, so I’m just going to free ride on his idea: a year end review. If I were to sum up the theme of this year in a word, that word would be irrational.

After 21 months of god awful presidential campaigning, we were finally left with a classic Kodos vs Kang election. The Democrats were certain that they could put forward any turd sandwich and beat Trump, but they ultimately lost out to populist outrage. Similar themes played out with Brexit, but I don’t know enough to comment.

Irrationality explains the Democrats, the Republicans, and the country as a whole. The world is complex, but big decisions have been made by simple people.

We aren’t equipped to manage the world’s complexity.

We aren’t made to have direct access to The Truth; we’re built to survive, so we get a filtered version of the truth that has tended to keep our ancestors out of trouble long enough to get laid. In other words, what seems sensible to each of us, may or may not be the truth. What we see with our own eyes may not be worth believing. We need more than simple observation to actually ferret out The Truth.

Our imperfect perceptions build on imperfect reasoning faculties to make imperfect folk economics. But what sounds sensible often overlooks important moving parts.

For every complex problem there is an answer that is clear, simple, and wrong.

Only a small minority of the population will ever have a strong grasp on any particularly complex thing. As surely as my mechanic will never become an expert in economics, I will never be able to do any real work on my car. The trouble arises when we expect me or my mechanic to try to run the country. The same logic applies to politicians, whose job (contrary to what your civics teacher thinks) is to get re-elected, not to be a master applied social scientist. (And as awful as democracy is, the alternative is just some other form of political competition… there is no philosopher king.)

But, of course, our imperfect perception and reasoning have gotten us this far. They’ve pulled us out of caves and onto the 100th floor of a skyscraper*. Because in many cases we get good enough feedback to learn a lot about how to accomplish things in our mysterious universe.

We’re limited in what we can do, but sometimes it’s worth trying something. The trouble is, I can do things that benefit me at your expense. And this is especially true in politics (also pollution–what they have in common is hot air!). But it’s not just the politicians who create externalities, it’s the electorate. The costs of my voting to outlaw gravity (the simplest way for me to lose a few pounds) are nil. But when too many of us share the same hare-brained idea, we can do some real harm. And many people share bad ideas that have real consequences.

Voting isn’t the only way to be politically engaged, and we face a similar problem in political discourse in general. A lot of Democrats are being sore losers about this election rather than learning and adapting. Trump promised he would have done the same had he lost. We’re basically doomed to have low-quality political discourse. It’s easy and feels (relatively) good to bemoan that the whole world is going to hell.

We’re facing rational irrationality. Everyone is simply counting on someone else to get their shit together, because each of us individually is more comfortable with our heads firmly up our asses.

It’s a classic tragedy of the commons and it should prompt us to find some way to minimize the harm of our lousy politics. We’ve been getting better at this over the centuries. Democracy means the levers of power can change hands peacefully. Liberalization has entailed extending civil and economic rights to a wider range of people. We need to continue in this vein. More freedom has allowed more peace and prosperity.

So what do we do? I’d argue that we should focus on general rules rather than trying to have flawed voters pick flawed politicians and hope for the best. I don’t mean “make all X following specifications a, b, and c.” I mean, if you’re mad, try and sue someone. We don’t need dense and exploitable regulations. We don’t need new commissions. We just need a way for people to deal with problems as they arise. Mind you, our court system (like the rest of our government) isn’t quite ready for a more sensible world. But we can’t be afraid to be a little Utopian when we’re planning for the long run. But let’s get back to my main point…

We live in an irrational world. And it makes sense that it’s that way; rationality is hard. We can see irrationality all around us, but we see it most where it’s cheapest: politics and Facebook. The trouble is, sometimes little harmless irrational acts add up to cause real harm. Let’s admit we’ve got a problem with irrationality in politics so we can get better.

*Although that’s only literally true in 17 cases.