- Why Orthodox Christian countries remain stuck Leonid Bershidsky, Bloomberg View

- How communist Bulgaria became a leader in tech and sci-fi Victor Petrov, Aeon

- Slobodian’s The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism Henry Farrell, Crooked Timber

- Rethinking the unitary executive in American politics Ilya Somin, Volokh Conspiracy

neoliberalism

Nightcap

- The end of empire and the birth of neoliberalism Deirdre N. McCloskey, Literary Review

- Gimme shelter: safe spaces and f-bombs in higher ed Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Can Fresno State fire a professor for being an ass on Twitter? Ken White, Popehat

- The worst effects of climate change may not be felt for centuries Charles C. Mann, TED Ideas

Dear Mr. Pirie, refrain from using the “neoliberal” label

A few days ago, Madsen Pirie of the Adam Smith Institute announced the publication of the Neoliberal Mind. Basically, Pirie accepts the grab-everything-we-don’t-like tag that many would-be thinkers have tried for decades to stick upon what we can refer to as the “liberal right” (I prefer the French expression of droite libérale). All he does is take the same message that classical liberals have been using for centuries and puts a new label on it.

It is a PR stunt. To be fair, I have often made the joke that there should be a New Liberal Party of Canada so that its members may be called the “neoliberals” so as to ridicule those who use the word. As such, I am poorly placed to frown upon Pirie’s book. Nonetheless, I wish that Pirie (and the folks at the Adam Smith Institute) would refrain from using the label.

Why? Because for years, the word “neoliberal” has been the most efficient sorting tool to separate the wheat from the chaff.

There is no generally agreed upon definition of “neoliberalism”. Everyone has its own spin on it. Sometimes, academics who use that word sometimes to mean what classical liberalism entails. In other instances, they speak about subsidies to certain companies as “neoliberalism”. Once, and I am not joking, I debated a policy analyst from a left-wing think tank who told me that rising levels of public spending to GDP could be qualified as part of a “neoliberal” agenda.

A concept without a concise definition which is meant to collect into a bag everything that is not liked is not a relevant one.

Generally, those who use the word have this épouvantail (the word strawman has a scarier sound in French) of the beast they claim to slay. But it is generally a caricature that does not hold basic scrutiny. They argue that “neoliberals” value profit and are “cold utility maximizers” who draw everything they believe from the cold hands of the economic sciences. They are generally unaware that economists (which are often lumped in the same bag as the main promoters of “neoliberalism”) adhere to no such simplicity. One merely needs to read James Buchanan, Vernon Smith, Elinor Ostrom, Deirdre McCloskey, Max Hartwell, William Easterly to be cleansed of this simplistic (and simpleton) view of the human mind. Using a concept that is ill-defined and does not even survive the most basic of ideological Turing tests has no value.

In the end, the sole value of those who spew the word “neoliberalism” is that they signal to readers and scholars that their work might be worth avoiding. To be fair, some of those who use the word produce interesting research and comments. Generally, they tend to use the word parsimoniously and they make it a point of honor to define it in clear and unambiguous terms. They are an exception and, generally, good research tends to be absorbed in the mainline if the point is valid. As such, the word “neoliberalism” is useful because it sorts out the wheat from the chaff.

I understand the PR value of accepting the cloak – which is what Pirie is doing. However, are we not forsaking the best weapon to identify bad social science in so doing?

From the Comments: Foucault’s purported nationalism, and neoliberalism

Dr Stocker‘s response to my recent musings on Foucault’s Biopolitics is worth highlighting:

Good to see you’re studying Foucault Brandon.

I agree that nationalism is an issue in Foucault and that his work is very Gallocentric. However, it is Gallocentric in ways that tend to be critical of various forms of nationalist and pre-nationalist thought, for example he takes a very critical line of the origins of the French left in ethnic-racial-national thought. Foucault does suggest in his work on Neoliberalism that Neoliberalism is German and American in origin (which rather undermines claims that Thatcherism should be seen as the major wave). He also refers to the way that Giscard d’Estaing (a centre-right President) incorporated something like the version of neoliberalism pursued by the German Federal Chancellor, Helmut Schmidt, from the right of the social democratic party.

Thoughts about the relations between France and Germany going back to the early Middle Ages are often present in Foucault, if never put forward explicitly as a major theme. I don’t see this as a version of French nationalism, but as interest in the interplay and overlaps between the state system in two key European countries.

His work on the evolution of centralised state judicial-penal power in the Middle Ages and the early modern period, concentrates on France, but takes some elements back to Charlemagne, the Frankish king of the 8th century (that is chief of the German Franks who conquered Roman Gaul), whose state policies and institutional changes are at the origin of the French, German and broader European developments in this are, stemming from Charlemagne’s power in both France and Germany, as well as other areas, leading to the title of Emperor of the Romans.

Getting back to his attitude to neoliberalism, this is of course immensely contentious, but as far as I can see he takes the claims of German ordoliberals to be constructing an alternative to National Socialism very seriously and sympathetically and also regards the criticisms of state power and moralised forms of power with American neoliberalism in that spirit. I think he would prefer an approach more thoroughly committed to eroding state power and associated hierarchies, but I don’t think there is a total rejection at all and I don’t think the discussion of ordoliberalism is negative about the phenomenon of Germany’s role in putting that approach into practice in the formative years of the Federal Republic.

Here is more Foucault at NOL, including many new insights from Barry.

Foucault’s biopolitics seems like it’s just a subtle form of nationalism

I’ve been slowly making my way through Michel Foucault’s The Birth of Biopolitics, largely on the strength of Barry’s recommendation (see also this fiery debate between Barry and Jacques), and a couple of things have already stood out to me. 1) Foucault, lecturing in 1978-79, is about 20 years behind Hayek’s 1960 book The Constitution of Liberty in terms of formulating interesting, relevant political theory and roughly 35 years behind his The Road to Serfdom (1944) in terms of expressing doubts over the expanding role of the state into the lives of citizens.

2) The whole series of lectures seems like a clever plea for French nationalism. Foucault is very ardent about identifying “neo-liberalism” in two different models, a German one and an American one, and continually makes references about the importation or lack thereof of these models into other societies.

Maybe I’m just reading too deeply into his words.

Or maybe Foucault isn’t trying to make a clever case for French nationalism, and is instead trying to undercut the case for a more liberal world order but – because nothing else has worked as well as liberalism, or even come close – he cannot help but rely upon nationalist sentiments to make his anti-liberal case and he just doesn’t realize what he’s doing.

These two thoughts are just my raw reactions to what is an excellent book if you’re into political theory and Cold War scholarship. I’ll be blogging my thoughts on the book in the coming weeks, so stay tuned!

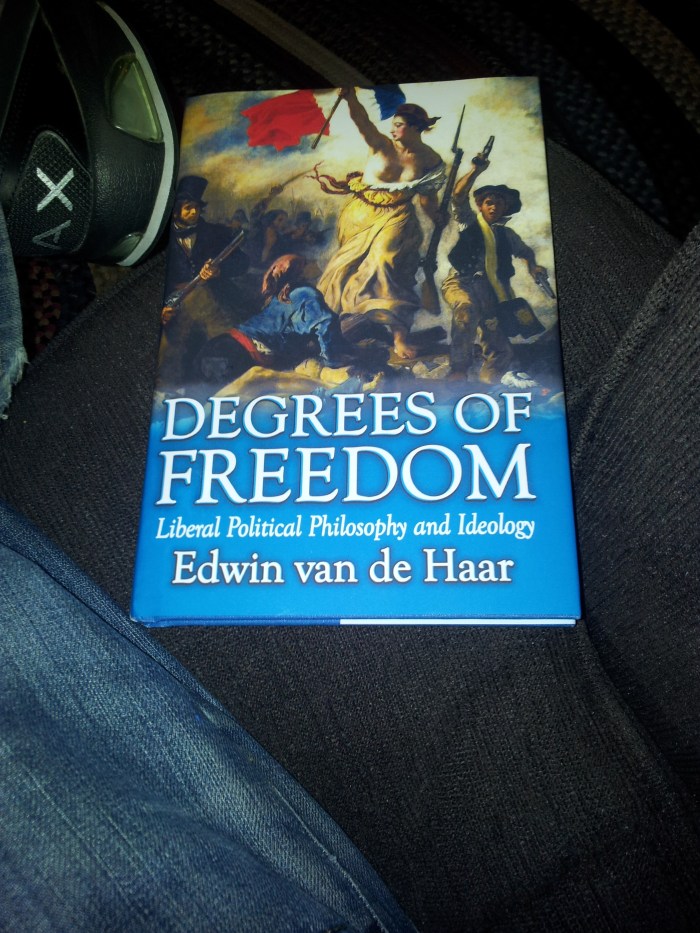

Look at what just arrived in my hands

It’s Dr van de Haar’s newest book, straight from the Netherlands. You can pick up your own copy here (mine was a gift from Dr V, one of the many perks of being an annoying blog editor!). He’s got more books that you can find either on his ‘About…’ page here at NOL or on the sidebar. Thanks Dr van de Haar!

I know Dr Khawaja (of Policy of Truth infamy) was thinking of getting this book reviewed for Reason Papers, too. I don’t have the training in political philosophy to do the job, but I can say, just by reading through the first couple of pages in his introduction, that I could have benefited immensely from this book if I had been introduced to it in Political Science 101.

Aside from the introduction, I also briefly read through Edwin’s section near the back of the book (pgs. 120-126) titled ‘The Neoliberal Phantom’, and believe that it would be very useful for liberals of all stripes when confronted with poorly constructed anti-liberal arguments (the geographer – NOT anthropologist – David Harvey, for example, gets the full Dutch treatment from Dr van de Haar). It should be noted that this section is probably (again, I don’t have any training in this area) a little less useful for academics confronting more sophisticated attacks against liberalism, but it’s a very good primer for intense undergraduates and graduate students who have to deal with the relentless, poorly reasoned attacks on liberalism in their studies and at seminars.

When I read the whole thing I’ll be sure to post a review here at the blog. If I get word of somebody who wants to review Dr van de Haar’s book for Reason Papers (check out what’s on tap right now, by the way), I’ll try to post the good news here, too.

How the Left Failed France’s Muslims: A Libertarian Response

Walden Bello, a sociologist in the Philippines, has a piece up over at the far-Left Nation titled “How the Left Failed France’s Muslims.” As with everything Leftist, it was packed with mostly nonsense coupled with a couple of really good nuggets of insight. The nonsense can be explained by the Leftist urge to attribute grand theories that don’t involve an understanding of supply-and-demand to problems dealing with oppression. Below is a good example of another weakness of the present-day Left:

Failure of the French Model of Assimilation

In the “French model,” according to analyst Francois Dubet, “the process of migration was supposed to follow three distinct phases leading to the making of ‘excellent French people.’ First, a phase of economic integration into sectors of activities reserved for migrants and characterized by brutal exploitation. Second, a phase of political participation through trade unions and political parties. Third, a phase of cultural assimilation and fusion into the national French entity, with the culture of origin being, over time, maintained solely in the private sphere.”

What the technocrats didn’t face up to was that by the 1990s the mechanism sustaining the model had broken down. In the grip of neoliberal policies, the capitalist economic system had lost the ability to generate the semi-skilled and unskilled jobs for youth that had served as the means of integration into the working class for earlier generations of migrants. Youth unemployment in many of the banlieues reached 40 percent, nearly twice the national average. And with the absence of stable employment, migrant youth lacked the base from which they could be incorporated into trade unions, political parties and cultural institutions.

Impeded by ideological blindness to inequality, political mishandling of the Muslim dress issue and technocratic failure to realize that neoliberalism had disrupted the economic ladder to integration, authorities increasingly used repressive measures to deal with the “migrant problem.” They policed the banlieues even more tightly, with an emphasis on controlling young males—and, most notably, they escalated deportations.

Notice how Bello doesn’t challenge the fact that the French government has a model for integrating human beings into a system it assumes is already in place? That’s the problem in Europe (and Japan/South Korea), but instead of acknowledging this – or even recognizing it as an issue – Leftists throw in terms like “capitalist economic system” and “neoliberalism” to explain away the failures of the French state’s central planning efforts. Naturally the real threat according to Bello is a Right-wing populism rather than the widespread, unchallenged belief (including by Bello) that government can assimilate one group of people with another in stages.

Just keep government off the backs of people, and they’ll associate in peace (peace is not the absence of conflict, of course, but only the ability to handle conflict through peaceful means, such as through elections or boycotts or marches or consumption). Does this make sense? Am I being naive here?

Ceding power to a central government in order to integrate immigrants into a society in a manner that is deemed acceptable to the planners is going to cause conflict rather than temper it. Planners are beholden to special interests (this is not a bug of democracy but a feature; ask me!), and they cannot possibly know how their plans are affecting the individuals being planned for. Immigrants, left largely to their own devices (which include things like communities, religion, and creativity), are beholden to their own interests (again, which include things like communities, religion, and creativity). Which way sounds less likely to cause resentment all around? Again, am I being naive here? Am I knocking down a straw man? Is this really how European governments approach immigration and assimilation? Is this really how the US approaches immigration and assimilation? These are genuine questions.

An even bigger question remains, of course: how can Europe better assimilate immigrants? Open borders, discussed here at NOL in some detail (perhaps better than most places on the web), is one option, but in order for open borders to work you need political cooperation, and political cooperation means more than just cooperation on matters that interest libertarian economists. Thus, I argue for federation instead of plain ol’ open borders. Another option would be to have governments in Europe cease planning the lives of immigrants for them. This option is a very viable short-term policy that probably does not get the attention it deserves because Leftists are currently unable to see the forest for the trees. Exposing neoliberalism and capitalism is, arguably, more important than petty day-to-day politics after all.

Another Liberty Canon: Foucault

Michel Foucault (1926-1984) was a French writer on various but related topics of power, knowledge, discourse, history of thought, ethics, politics, and so on. His name to some summons negative associations of French intellectual fashion, incomprehensibility, and refinements of Marxist anti-liberty positions.

However, his influence in various fields has become too lasting, and too much taken up by people who do not fit into the categories just mentioned, for such reactions to be considered adequate. Foucault himself resisted and mocked labels, which was a serious issue for him because in his work he tried to question the absolute authority of any one system of knowledge and the authority of isolated great thinkers.

He said that once he had written something it was no longer what he thought, which is in part a playful attempt to resist labelling, but also a rather serious point deeply embedded in his thought, about the nature of subjectivity, how it is always more than what we say or more than the identity that power relations impose on us.

It seems to me that any ethics of subjectivity has pro-liberty implications, and despite the image some might have of Foucault as morally irresponsible or indifferent, he increasing developed the idea of self-invented subjectivity, based on care of the self, the art of existence, and related terms.

The self-invention does not mean that Foucault thought we can arbitrarily will our self to be anything, it does mean that he thought we have possibilities to cultivate ourselves to live in a way that relates to, and challenges our existing strengths and goals.

Despite the image for some of intellectual fashion round Foucault, these ideas were partly developed through study of Ancient Greek and Roman ideas about ethics and style of living, which included interaction with scholars in the field.

Another theme he developed through his interests in antique knowledge and culture was that of ‘parrhesia’, Greek word that refers to free speaking, which in the context of ancient city states, particularly the Athenian democracy, had strong overtones of courage in truth telling before the city assembly, a prince of any other source of power.

The ethic of truth telling relates to Foucault’s own work on the language of knowledge and the history of science, as well his political ideas. He did not believe in absolute final systems of knowledge, autonomous of context, but he did believe that trying to find truths within whatever perspectives was an ethical enterprise connected with the kind of self cultivation he advocated.

Foucault’s own father had been a doctor and on at least one occasion Foucault suggested his own work was a continuation of the doctors work that evidently combines ethical and scientific aspects. It must also be said that Foucault was a great critic of the authority of experts, including doctors, so he might also be seen as struggling with the memory of his father.

The ambiguity and the personal involvement in ideas suggested there is very much at work throughout Foucault’s writing, in its tension and energy. It is part of his ‘difficulty’, which also comes from the philosophical and literary interests he had, which relate to the creative possibilities of linguistic disruption. We can see that in the most obvious way when he quotes literary texts of Borges, Beckett and so on.

The existential commitments in Foucault’s work is clear if we think about the book that made him famous, History of Madness (also known as Madness and Civilisation), and his personal experience of mental ill health and psychiatric treatment, particularly in his student years.

We can also think about his constant critique of power and his individual willingness to physically confront power, as in the beatings he received from the police at demonstrations for rights in both France and in Tunisia (where he taught for a few years just after becoming a celebrity public intellectual in France).

Returning to the topic of experts and power, one of Foucault’s most pervasive ideas now is of ‘biopolitics’, that is the way that power expresses itself through prolongation of life. As the state has moved from a basis in the power of death over criminals and other supposed enemies, to a promotion of population, public health, and prolongation of life, it has demanded corresponding powers of intervention and control.

At the extreme this means the ‘racial hygiene’ ideas that German National Socialists used to justify the Holocaust, and in a more routine way means expanding state activity justified by public health goals. We can readily see the contemporary significance of Foucault’s ideas here in relation to ever expanding state and ‘expert’ attempts to limit smoking, drinking alcohol and supersized fizzy drinks, eating sugary and fatty foods, and so on.

The ideas about biopolitics builds on the discussion of modern power in maybe his most widely read book, Discipline and Punish, which deals with the way that the prison becomes the central means of punishment after the eighteenth century Enlightenment, and suggests the dangers of Enlightenment becoming a controlling form of rationalism.

The way the prison works, around observation, or surveillance, of prisoners to ensure adherence to prison routine was the model of modern power for Foucault including factories, schools, and armies, in a model of ‘disciplinarily’. Again Foucault’s intellectual interests correspond with life commitments, as he was a prominent campaigner for prisoner rights, under the inspiration of the man with whom he shared his life, the academic sociologist Daniel Defert.

Foucault’s analyses in Discipline and Punish, and related material, draw on the ‘classical sociology’ of Emile Durkheim and Max Weber with regard to norms and authority, as his views on the emergence of the modern state draw heavily on the ‘pre-sociology’ to be found in the historical and social work of the classical liberal thinkers Charles-Louis de Secondat, Baron of La Brède and Montesquieu and Alexis de Tocqueville.

There is some drawing on Marx, but one should be wary of those left socialist inclined advocates of Foucault who emphasise this strongly, since they don’t mention the other points of orientation so much. The same applies to remarks Foucault made about the importance of the twentieth century Marxist theory of the Frankfurt School, as those who emphasise such remarks ignore accompanying remarks about the importance of Max Weber and ‘Neoliberalism’ (i.e. classical liberal and libertarian thought since the Austrian Liberal school of Menger, Hayek, Mises etc).

Strange as it might seem, Foucault suggests we take Marx, Weber, the Frankfurt School, and Neoliberalism together as attempts to explore liberty and power. Maybe it shouldn’t seem so strange, however awful the consequences of Marxist ideas coming in power have been, that does not mean we should ignore Marx and Marxism, which starts by drawing heavily on classical liberalism and does have some noteworthy things to say about constraints on liberty in a capitalist society, even if offering bad solutions.

Certainly Foucault is not your man if you think a pro-liberty position means uncritical embrace of the links between private enterprise and state power, but since the liberty tradition has in a very significant way been concerned with criticism of rent seeking and crony capitalism, of the drives within capitalism to betray itself, then I don’t think we need to reject Foucault in this area. Indeed it is even a part of the liberty tradition to reject ‘capitalism’ as tied to the state and concentrations of power and argue for markets, property, and association rights liberated from state alliances with economic power.

This is the core of left-libertarianism, and even Foucault’s most Marxist leaning fans would find it hard to deny that left-libertarian is an appropriate label for Foucault. Clearly he was a natural maverick and critic of all power, including state socialist power. I suggest his life, his activism, and his writing, can be taken as an inspiration for all liberty-inclined people. Even on the more conservative side, Foucault’s thoughts about self-cultivation are a version of virtue theory, of an emphasis on cultivating virtue, so Foucault has a lot to offer to all streams of liberty thought.

Those Foucault texts most relevant to political thought about liberty

Monographs

History of Madness (also published as Madness and Civilisation)

Discipline and Punish

History of Sexuality (3 volumes: Will to Knowledge, The Uses of Pleasure, The Care of the Self)

Collected lectures

(Foucault’s rather early death means that much of his work was in lectures that would have been later revised into published material. The task of bringing those lectures into print is still underway).

Fearless Speech

The Government of Self and Others

The Birth of Biopolitics

Security, Territory, Population

Hermeneutics of the Subject

Society Must be Defended

Neoliberalism: When French philosophy thinks about American economics

From an economic perspective, the vision of man becomes very, very poor. Man is a being who responds to stimuli from the environment, and we can modify his behavior with a choice of stimuli. And what government is, what power is, is the use of different kinds of stimuli. The economic theory gives a set of tools, a “good manner” to use stimuli to obtain the right comportment. In this respect, the result of the theory, perhaps, is to produce a vision of man that is very impoverished.

This is French philosopher François Ewald taking a moment away from his task of explaining Foucault’s thoughts on Gary Becker’s work to elaborate his own thoughts on the discipline of economics. Read the whole thing (pdf). It’s a short paper on Michel Foucault’s thoughts about American liberalism (or neoliberalism) and particularly Gary Becker’s work.

Keynesianism, the Global Economy, and Responsibility

Economist Joseph Stiglitz has an op-ed out in Project Syndicate lamenting bad policies for the current economic stagnation of the West. This response comes from economist Peter Boettke, and I think it is an important and woefully neglected one:

Since 2008, and before, [Stiglitz] has been constantly complaining about neo-liberal policy and how its lack of attention to the appropriate regulatory framework and disregard for fundamental policy priorities has produced the mess we are in. In fact, he made the argument very simply even while he was in positions of tremendous political power in the Clinton administration and at the World Bank — if only the world would listen to me, and engage in the appropriate interventions then the mess would be avoided. But who were the so-called neo-liberals that weren’t listening to him? What neo-liberal thinker had the same powerful positions that he held? Did F. A. Hayek or Milton Friedman actually come back from the grave to serve as head of the CEA or as Chief Economist at the World Bank? Or did all this disruptive inequality and global imbalance happen on the watch of other thinkers.

I think Boettke is right, but I also think both economists are wrong in a sense, too. First of all, global poverty over the past twenty years or so has been halved thanks to the very neoliberal policies that both economists are disagreeing about, and that both economists have more or less endorsed. With this important, praiseworthy accomplishment in mind, why would these guys want to spend so much time pointing fingers at each other?

I know why they are pointing fingers (because of the terrible shape that Western economies are in), but I am a little baffled at the audacity of Stiglitz and other Keynesians who have held the levers of power for sixty years to point the finger at something other than themselves.

Really quickly: Some of might ask why Boettke and Stiglitz agree on neoliberalism abroad and disagree on policy at home. My short answer would be because the West already has the institutions (property rights, other individual rights, etc.) that economists have identified as necessary for a market order, so their debates about policy occur within the same theoretical framework. Post-colonial states (“developing states”) have virtually none of the institutions that the West, and so it easy for economists with different theoretical paradigms to agree on generalities concerning these developing countries (“they need to open up to world trade and focus on property rights before they do much else”). Does this make sense?

What’s Up with New Zealand?

Economist Scott Sumner’s 2010 piece on the unacknowledged success of neoliberalism (which I linked to yesterday and you should definitely read or reread) poses an interesting question:

There are two obvious outliers [to aggressive neoliberal reforms]. Norway, the highest-income country, is much richer than other countries with similar levels of economic freedom, and New Zealand, at 80 on the economic freedom scale and only $27,260 in per capita income (US PPP dollars), is somewhat poorer than expected […] Perhaps New Zealand’s disappointing performance is due to its remote location and its comparative advantage in agriculture holding it back in an increasingly globalized economy in which many governments subsidize farming.

Rather than challenge Sumner’s thoughts as to why New Zealand is much poorer (I think his guess explains a lot), I think I can add to it: The Maori.

The Maori are the indigenous inhabitants of New Zealand, and can be compared – socially – to the Native Americans of the New World or the aborigines of Australia. Unfortunately I know next to nothing about the Maori (or other South Pacific cultures), but I do know how to draw rough inferences about things by using data!

The Maori comprise about 15% of New Zealand’s population, whereas in other states settled by Anglo colonies the population of the natives relative to the overall population of the country is minute (aborigines in Australia comprise 3% of the population, for example, and in Canada and the US the indigenous make up about 2%).

The relatively large percentage of indigenous citizens in New Zealand can better explain why New Zealand is an outlier among rich countries, but I also think it’s important to ask why the Maori (and other indigenous populations in Anglo-settled colonies) have failed to match the demographic trends of their European and Asian counterparts.

Institutions are, to me, the obvious answer, but I’m curious as to what the rest of you think. I’d also like to add that I don’t think enough of us think about the issue of land (as in ‘land, labor and capital’ when we discuss the huge demographic gaps found between – for lack of better terms – settlers and natives in Anglo-American countries).

Around the Web: Highly Recommended Reading Edition

- Fantastic post about Uganda’s role (and a Ugandan’s perspective) in the ongoing South Sudan conflict.

- Sexual mores: Love in a cold climate. I live in California, but my ancestors come from the frozen wastelands of Scandinavia and northern Germany. Rawr!

- The unacknowledged success of neoliberalism.

- One of my favorite bloggers (Scott Sumner) is joining one of my favorite group blogs (EconLog). I’m a huuuuge fan of group blogs (they’re pretty much the only type of blog I read), so I hope he decides to stay on as a permanent contributor.

- Inglorious Revolutions. Why the West is kinda, sorta hypocritical when it comes to the Arab Spring.

Research Readings

I’m trying to get through the rest of Eugene Rogan’s The Arabs: A History and Steven Gregory’s Devil Behind the Mirror for classes, but I’ve also stumbled across what looks to be a pretty fascinating research paper on neoliberalism by a political scientist at a university in Canada. The abstract:

This article examines and theorizes neoliberal ideas related to the scale as pects of multilevel governance. It argues that neoliberalism contains a self conscious normative project for multilevel governance which is consistent across the federal, regional and global levels. It further argues that the underlying logic of this project can be usefully theorized through various critical understandings of the separation of the economic and the political in neoliberalism and, in particular, through Stephen Gill’s concept of new constitutionalism. To demonstrate these points, the article draws on the normative work of neoliberal organic intellectuals – including Hayek, Friedman, Buchanan and various neoliberal think tanks – on ‘market-preserving federalism’ and the more recent extrapolation of these ideas to the regional and global levels.

The full article is here, but it is probably gated. *sigh* It’ll be interesting to see what the author comes up with. I’ll keep y’all posted.

Property Rights in the Post-Colonial World

Land grabs and crony capitalism at its finest. From Reason magazine:

Politicians in the affected countries are key partners in operations that resemble the late-19th-century scramble for control of Africa. The land grabs aim at enriching privileged companies and their political allies, usually at the expense of those already on the land. States, companies, and their frequent close friend, the World Bank, see no reason to respect sitting owners and resource users, whatever their rights under customary law and (sometimes) postcolonial statutes. Pastoral nomads get even less respect. In Tanzania, for example, governments and safari capitalists have reduced the traditional grazing lands of the Maasai herdsmen to a fraction of what they were. And in Ethiopia, the government’s “villagization” policy, Pearce writes, resettles peasant farmers “in the manner of Stalin, Mao, and Pol Pot,” clearing the way for deals with foreign capital.

You can read the rest here. I hope to have some more academic articles up as links soon.

Life Under Fatwa

I did once visit Iran when I was 21 years old, during the time of the shah. It was wonderful. I had just graduated from university, and such was the world at that time, 1968, that I was able to drive with a friend from London to South Asia across the world. I mean, try driving across Iran and Afghanistan now! I remember it being a very cosmopolitan, very cultured society. And it always seemed to me that the arrival of Islamic radicalism in that country, of all countries, was particularly tragic because it was so sophisticated a culture — which is not to defend the shah’s regime, which was appalling. But it was one of the tragedies of history that an appalling regime was replaced by a worse one.

At first I found his praise for the Obama administration to be typical of Left-wing establishment figures, but then I remembered that Rushdie is an Indian and had probably had to deal with racist legislation in one form or another while growing up. While the period of colonialism (roughly coinciding with the end of the Napoleonic Wars and the beginning of World War I) did indeed open up more places to markets, the Jim Crow-like legal barriers that European states erected no doubt helped to foster part of the suspicious climate that now pervades most globalization skeptics worldwide.

This is a shame for two reasons: Continue reading