globalization

Lunchtime Links

- Globalization and Political Structure [pdf] | what’s a monopolis?

- Protestantism and the Rise of Industrial Capitalism in Nineteenth Century Europe [pdf] | who was James Cooley Fletcher?

- Primed against primacy: the restraint constituency and US foreign policy | polystate, book 2

- Nation-building, nationalism, and wars [pdf] | against libertarian populism

BC’s weekend reads

- Cairo’s Chinatown

- Informational post on Turkish grand strategy

- Free speech for me, but not for thee (SPLC edition)

- Experts and the gold standard and, really, a big key to continued economic development

- A bunch of new earth-like planets have been found. The Long Space Age (peep the dates)

A beautiful bit of small world mojo

The first time I went to Boston was to look for an apartment. On my last day I was hanging around Downtown crossing. Gmail confirms it was June 12th, 2010. I was having a polish sausage, and this guy approached me. I don’t remember what we talked about, but we chatted for a few minutes. Good town. That sort of thing is exactly what I’d expect in SLO (Central Coast California) or Santa Cruz… but this was in a place with a skyline! Anyways, he wasn’t in a cult and I didn’t get robbed.

Flash forward to some time that fall. I was in Inman Square and saw a chair left on the curb for anyone who needed a chair. I needed a chair. I lived in Union Square, but that was just the next neighborhood north (if I lived on Prospect Hill, there’s no way that chair would have made it, but I might have realized that before picking it up). So I pick up this chair and walk. Google Maps puts my route at 0.5 miles. I got a couple blocks short of that before I crap out. Fortunately I’ve got a place to sit down. So I’m sitting in an easy chair on the sidewalk, hauling it forward a few yards, and plopping down again.

Across the street, someone’s trying to get my attention. He comes over, and he’s the guy I’d randomly met months earlier. He lives across the street from me! And he helps me carry home my chair. We have a beer and chat.

Flash forward to Thanksgiving of that fall. I’m hanging out by myself. This is my first Thanksgiving alone. Neighbor guy knocks on my door and invites me over. Inside are a bunch of his musician friends, and this fantastic music is coming from one of the bedrooms. An impromptu jam session is playing the sort of dusty sounding blues I’m enamored with at the time. After they finish I mention that it sounds like this African blues guitarist, Ali Farka Toure. It turns out I pronounced his name right, because I’m immediately informed that his son was playing guitar just now!

Just now I was listening to Spotify, and a song reminds me of another song which led me to the song above from that album I’d bought when I lived in SLO and was trying to be worldly. Absolutely fantastic music, a mish-mash of cultural influences bouncing back and forth around the world, and I got to experience something of it first hand because of the grace and generosity of a fellow human.

But more than that, a mix of technology, globalization, and absolutely random chance created that beautiful memory and triggered it again just now. We live in a beautiful world.

Coase’s “Nature of the Firm”: An Anthropological Critique

But is it a good one? Is it even made in good faith? I need help.

From American anthropologist John D Kelly’s The American Game…:

Ronald Coase’s theory of the nature of the firm rescued, for neo-classical economics, the existence of firms or corporations as rational entities […] Markets always come first, and the problem of the existence of firms is depicted as the problem of why a rational manager would rely on employees rather than markets. State planning and private firms are taking over what already exists, integrated by the price mechanism of markets, and are successful to the extent that they lower costs, since there are a variety of costs involved in market transactions. Thus marginalist analysis implies that an equilibrium will always be found between planning structures and integration by price mechanism, especially since, as Coase says in “The Nature of the Firm,” “businessmen will be constantly experimenting, controlling more or less” and “firms arise voluntarily because they represent a more efficient method of organizing production.” The rise of the firm, as Coase imagines it, is always a movement from many pre-existing contracts to a controlling structure, “For this series of contracts is substituted one.” (94)

The emphasis is mine. Kelly continues:

This imaginary fits poorly the situations that were precisely the actual origins of firms, as when banks gave mortgages to planters, or stock markets funded companies of young agents, prepared to cut plantations into captured wilderness for tropical commodities […] usually employing labor moved long distances and disciplined by direct violence. There is more in the universe than Coase’s imagination, more motives for controlling powers of firms than their cost efficiencies. (94-95)

Kelly goes on to give a brief account of 1) how corporations created commodity production out of thin air, 2) how these corporations were tied to European imperialism, and 3) how they used slaves and indentured servants even when it would have been cheaper to hire the locals.

I want to address Kelly’s summary of Coase’s paper (here is a pdf, by the way, in case you want to follow along), mostly because I’ve never read it although I know it’s important, but first I want to make a couple of digressions. Libertarians would more or less answer Kelly’s three charges listed above as follows: 1) yes, and this is a good thing, 2) state-sponsored corporations and private firms are two distinct entities with two very different incentive structures, and 3) see #2. There is also an issue of accuracy in regards to Kelly’s brief summary of world history since 1600. I don’t want to get into the details here, but I do want you to recognize that I am reading Kelly critically. My last digression is simply to point out that libertarians and Weberian Leftists like Kelly have more in common than we think.

To get back to Coase’s paper, and Kelly’s critique of it, I want to highlight one sentence from Kelly’s book in particular and then turn it over to the peanut gallery in the hopes of gaining some insight:

Markets always come first, and the problem of the existence of firms is depicted as the problem of why a rational manager would rely on employees rather than markets.

Is this the puzzle Coase was trying to grapple with in his paper? I ctrl+f’d Coase’s paper (“employe” – not a typo) and couldn’t find anything that actually confirms Kelly’s summary, but it would be an interesting project (if I am right in stating that Kelly’s summary of Coase’s paper is not accurate) to follow this line of thought and delve into Kelly’s insight about the reliance that entrepreneurs/firms have on employees (rather than markets)…

Forget income, the greatest outcome of capitalism is healthier lives!

Yesterday, James Pethokoukis of the American Enterprise Institute posted, in response to Bernie Sanders’ skepticism towards free market, that capitalism has made human “fantastically better”.

I do not disagree – quite the contrary. However, Pethokoukis makes his case by citing the fact that material quality of life has increased for everyone on earth since the early 19th century. I believe that this is not the strongest case for capitalism. The strongest case relies on health. This is because it addresses an element that skeptics are more concerned about.

Indeed, skeptics of capitalism tend to underline that “there is more to life than material consumption”. And they are right! They merely misunderstand that the “material standard of living” is strongly related to the “stuff of life”. For them, income is of little value as an indicator. Thus, we need to look at the “quality of human life”. And what could be better than our “health”?

The substantial improvement in the material living standard of mankind has been accompanied by substantial improvements in health-related outcomes! Life expectancy, infant mortality, pregnancy-related deaths, malnutrition, risks of dying from contagious diseases, occupational fatalities, heights, the types of diseases we die from, quality of life during old age, the physical requirements of work and the risks related to famines have all gone in directions indicating substantial improvements!

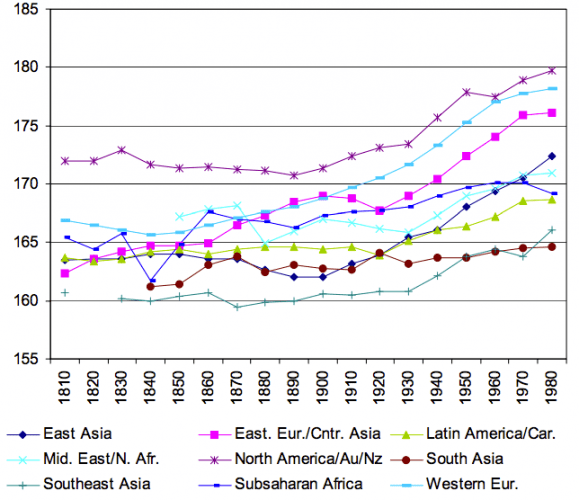

My favorite is the case of height. Human stature is strongly correlated with income and other health outcomes (net nutrition, risks of disease, life expectancy, pregnancy-related variables). Thus it is an incredible indicator of the improvement in the “stuff of life”. And throughout the globe since the industrial revolution, heights have increased (not equally though). Over at OurWorldInData.org, Max Roser shows this increase since the 1800s (in centimeters)

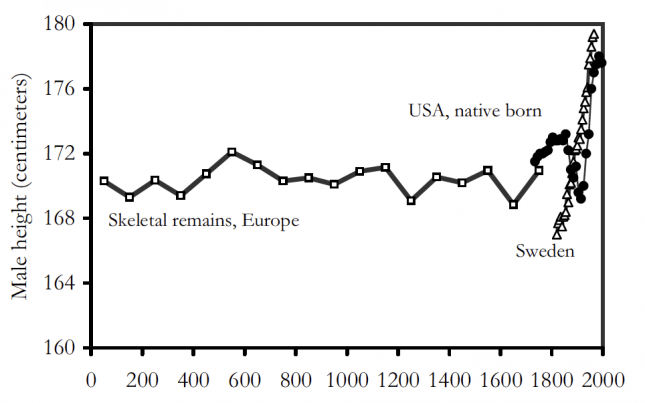

However, the true magnitude of the increase in human heights is best seen in the data from Gregory Clark who used skeletal remains found in archaeological sites for ancient societies. The magnitude of the improvement is even clearer through this graph.

The ability of “capitalism” to generate improvement in material living standards did leak into broader measures of human well-being. By far, this is the greatest outcome from capitalism.

South Asia and the Glass Ceiling

That is the broad topic of my latest article (pdf), which was just published by Pakistan Journal of Women’s Studies: Alam-e-Niswan. Here is the abstract:

South Asia is one of the most violent societies in the world, and also the most patriarchal. Both characteristics have led to continuity of violence, in which women are the silent and non-recognised victims. The situation is such despite the fact that women have occupied the highest office in their respective countries. The post-1991 wave of globalisation has led to the emergence of two parallel societies, based on different values, in almost all South Asian countries. In both societies women are being exploited and violence has been unleashed on them. Revolution in information and communication technology has helped in the dissemination of patriarchal values through ‘objectification’ of women in the name of ‘liberation’ from the grip of tradition. These patriarchal trends are clearly reflected in the making of domestic policies as well as formulating foreign policies of South Asian states. In such a situation, an academic argument for feminist foreign policy is relevant, though not encouraged by social actors.

You can also find the article on my ‘About…‘ page here at NOL.

What I’m reading (but not yet writing about)

I have been reading a lot lately. I apologize for the lack of blogging on my part. I am reading through Mestizo Logics by the French anthropologist Jean-Loup Amselle, Degrees of Freedom by our own Edwin van de Haar (a Dutch political theorist), and A Cat, A Man, and Two Women by the Japanese novelist Junichiro Tanazaki. I’ll be blogging about Amselle’s book in the near future, so stick around!

I am also reading through some excellent papers on colonialism.

Michelangelo: I gave apples to the ladies and cigars to the gentlemen (and to a couple of ladies in the English Dept). That was as an undergraduate though…

BC’s weekend reads

- Worldwide weeds

- The Mushroom That Explains the World

- …True Tales of Dharma, Demons, and Darwin

- From Spain to the New World via Florence and Vermont (be sure to scroll through the ‘comments’ thread)

- Time for Bolivians to Forget about the Sea (weak, but a good starting point for a discussion)

- Dissolution of the Templars

Migration from Bangladesh: Causes and Challenges

Migration and emigration from Bangladesh is a regular phenomenon. Historically, large scale migration from the region constituting present-day Bangladesh started after the tea plantation was introduced in Assam by the British rulers in the early nineteenth century. Large numbers of coolies (porters) were needed for the tea gardens. To fulfil that demand the Assam Company began to import labourers from Bengal (especially from its eastern part) in 1853. In contemporary times, the first batch of emigrants from Bangladesh were the ‘refugees’ seeking shelter in a foreign country, after atrocities started by the Pakistan Army in East Pakistan in 1971. This phenomenon did not stop even after the East Pakistan was liberated and Bangladesh was formed in 1971. Instead, since then many Bangladeshis have been migrating to Europe, West Asia, India, and East Asia. Migration has its impact on the demographic composition of the host countries. For example in some cities of Italy, like Lazio, Lombardy, and Veneto, the migrants from Bangladesh comprise a significant number of the population. In developed countries most of these migrants are engaged in service sector jobs like souvenir selling, or being a vendor, shop worker, restaurant waiter, or domestic maid.

Causes for large scale Migration from Bangladesh

Although its economy is stable, maintaining between 5-6 percent Gross Domestic Product (GDP) growth for the last two decades, it is not viable enough to occupy all skilled, semi-skilled, and non-skilled workers in the country. Statistically, only 26 percent of its population lives below the national poverty line of US$ 2 per day, but a substantive percentage remains unemployed or underemployed. To evade poverty, unemployment, and under employment, many Bangladeshi migrate to other countries. Often, they do so even at the cost of their lives. Many times, such a desperate act has lead them to be trapped in a situation like the one happened in May 2015, when about 8,000 people consisting of Rohingyas from Myanmar and Bangladeshis were stranded at sea close to Thailand. While moving illegally, many Bangladeshis have even lost their lives. The most recent high profile case of death of Bangladeshi migrants occurred on 28 August 2015 in North Africa, where at least twenty four Bangladeshis, including two minor children, died after two boats carrying up to 500 migrants sank off the coast of Libya. The first boat, which capsized early on 27 August 2015, had nearly 100 people on board. The second, which sank later, was carrying about 400 passengers.

As 80 percent of Bangladesh’s geographic area is situated in the flood plains of Ganges, Brahmaputra, Meghna, and many other small rivers, a contributing push factor to the migration is the character of these deltaic rivers. They often change their course, forcing many inhabitants to move to new settlements. The submergence of chors (silt areas) during the flood season forces many inhabitants, deliberately or out of sheer ignorance, to migrate into India. Out of these total number of environmental migrants, only a few return after the normalisation of the situation; others look out for ways to earn their livelihood in their ‘acquired ‘or ‘adopted’ land.

Changing Gender Pattern and Consequences of Migration

Gender-wise, like other countries from the developing world, the migration-related statistics of Bangladesh too is tilted in favour of males, of which there are around three million working in different parts of the world. But in last few years there has been a constant increase in the number of female migrants, who can migrate either alone or as a spouse. As reported in the Daily Star (a well-respected English language daily in Bangladesh), according to the June 2015 statistics of Bangladesh’s Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training (BMET), a total of 37,304 female workers had gone to different countries in 2012; it has increased to 76,007 in 2014. One country which stands out in terms of employment of female workers from Bangladesh is the United Arab Emirates (UAE). According to the BMET statistics, the UAE is home to 27 percent of the total female migrant workers of Bangladesh. Two basic reasons can explain this rising trend. Firstly, the demand for female workers in the UAE is higher than that of other countries. Secondly, attractive salary in the UAE draws more female migrant workers there than other countries. After the UAE, Lebanon hires a large number of female migrant workers. While the country has only 1.3 percent of total Bangladeshi migrants, it nevertheless has the second highest percentage of female migrants (24.3 percent) compared to all other countries. About 97,000 female workers reside in Lebanon.

Host countries remain hostile to the migrants. Sometimes, under pressure from political and economic constituencies, the host country (ies) restricts its visa policy for the citizens of a particular country or even denies issuing it to them altogether. The migrants are accused of ‘cultural invasion’ through demographic transition. They are also blamed for taking away job opportunities from the locals. Quite often, the migrants face violence from the locals, which is a sign of an extreme form of hatred towards them. Bangladeshi migrants have faced both situations. In 2014 Saudi Arabia stopped issuing visas for Bangladeshis even for the Umrah (a pilgrimage to Mecca performed by Muslims; it can be undertaken at any time of the year, in contrast to the Hajj). The Saudi officials claimed that in 2014 many Bangladeshis for whom Umrah visas were issued did not return to their country after performing the ritual. The Umrah visa was restored on August 5, 2015, after Bangladeshi foreign minister Md Shahriar Alam’s visit to Saudi Arabia, where a request was made to the Saudi State Minister for Foreign Affairs (Nizar bin Obaid Madani) for Umrah visas to be resumed.

Termed as ‘illegal’, the Bangladeshi migrants have faced violence in the Indian states bordering Bangladesh. The radical groups in the area have centuries-old grievances against them. They are considered to be an economic and cultural threat to the region. Many contrasting figures are being presented by these groups to justify their position; in reality, according to the United Nations data of 2013, the number of Bangladeshi in India is around 3.2 million. Migrants from Bangladesh have faced violence not only in India, but in other parts of the world too. In Thailand there have been rampant cases of exploitation of Bangladeshi women working in various sectors, including the flesh trade. In West Asian countries, the women workers are forced to work in many houses as a maid and beaten when they demand salary from their ‘masters’. In Malaysia, too, the cases of abuse of maids is on the rise. Most of these maids are from Bangladesh. In February 2015 Bangladeshi workers faced targeted violence in Rome, Italy.

Conclusions

Remittances play a crucial role in pushing the Bangladeshi economy. According to the World Bank, total remittance received by Bangladesh in 2013 was $14.5 billion, which has increased to $ 15.0 billion in 2014-15. In 2014, the remittances constituted 8.21 % of the GDP of Bangladesh. In January-March 2015 quarter Bangladesh earned $ 3771.16 million of remittance, which is 8.49 percent higher than the previous year. These remittances have helped Bangladesh’s economy maintain its 5.5- 6 percent GDP growth.

Though the migrants are important to Bangladesh’s economy, many serious ill effects of migration too have emerged. Under the guise of migration, human trafficking is taking place from Bangladesh to many parts of the world. Women and children from Bangladesh are trafficked into India, East Asia, and West Asia for commercial sexual exploitation and to serve as bondage labour. To check this activity, especially human trafficking of females, the government of Bangladesh issues licences to the recruiting agencies, which are renewed at regular intervals of time and maintained by the concerned agency. Also, in 2013 the Government of Bangladesh revised the Overseas Employment and Migration Act which includes Emigration Rules, Rules for Conduct and Licensing Recruiting Agencies, and Rules for Wage Earner’s Welfare Fund. Despite all such steps migrants are being exploited by the domestic agencies and they face umpteen challenges in the host country they end up in.

Strange Historical Facts

Not long thereafter, they erected the first sawmill in what was to become the state of Washington on a site by the lower falls of the Deschutes River. Much of the capital for erecting the mill apparently came from George W. Bush, Washington’s first black resident. The cut of this mill, it has been claimed, was marketed through the Hudson’s Bay Company at Fort Nisqually and found its way to Victoria and the Hawaiian Islands. The first shipment was supposedly made on the Hudson’s Bay Company steamer Beaver in 1848.

Um, wow. I don’t know where to begin. This excerpt comes from page 25 of a 1977 book by historian Thomas R Cox titled Mills and Markets: A History of the Pacific Coast Lumber Industry to 1900. Aside from the interesting anecdote quoted above, it’s not very good. I picked it up because of the possibilities associated with such a subject, but instead of a theoretical narrative on globalization, identity, state-building, and property rights, it is a book that reads a lot like the excerpt I quoted above (the local history aspect I have enjoyed, though; local history is one of my secret pleasures, the kind of stuff that never makes it into grand theoretical treatises but always lights up my brain because of the fact that places I know and places I have lived are the focus of the narrative).

I blame it on the year it was published, of course. 1977 was at the height of the Cold War, which means that scholarly inquiry was inevitably going to be policed by ideologues, and also that works appraising global or regional scales and scopes just weren’t doable. For instance, there was virtually no mention of Natives in the book. (See archaeologist Kent Lightfoot’s excellent, highly-recommended work – start here and here – for more on how this is changing.)

Guantanamo: A Conservative Moral Blind Spot

A current Guantanamo detainee, Mohamedou Slahi, just published a book about his ordeal. The book is redacted of course but it still tells an arresting story.

M. Slahi was captured in 2000. He has been held in detention, mostly at Guantanamo prison since 2002 but in other places too . The motive was that he supposedly helped recruit three of the 9/11 hijackers and that he was involved in other terror plots in the US and Canada (unidentified plots.).

Slahi admits to traveling to Afghanistan to fight in the early 1990s, when the US. was supporting the mujahedin in their fight against the Soviet Union. He pledged allegiance to al Qaeda in 1991 but claims he broke ties with the group shortly after.

He was in fact never convicted. He was not even formally charged with anything. Slahi has spent 13 years in custody, most of his young adulthood. If he is indeed a terrorist, I say, Bravo and let’s keep him there until the current conflict between violent jihadists and the US comes to an end. Terror jihadists can’t plant bombs in hotels while they are in Guantanamo. And, by the way, I am not squeamish about what those who protect us must do to people we suspect of having information important to our safety. I sometimes even deplore that we do to them is not imaginative enough. And, I think that the recent allegations to the effect that torture produces nothing of interest are absurd on their face.

But what if the guy is an innocent shepherd, or fisherman, or traveling salesman found in the wrong place? What if he is a victim of a vendetta by the corrupt police of his own country who delivered him over? What if he was simply sold to our intelligence services? What if, in short, he is has no more been involved in terrorism than I have? The question arises in Slahi’s case because the authorities had thirteen years to produce enough information, from him and from others, to charge him. They can’t even give good reasons why they think he is a terrorist in some way, shape or form. It shouldn’t be that hard. If he so much as lend his cellphone to a terrorist I am for giving him the longest sentence available. or simply to keep him until the end of hostilities (perhaps one century).

And if having fought in Afghanistan and having pledged allegiance to Al Qaeda at some point are his crimes, charge him, try him promptly even by a military commission, or declare formally, publicly that he is a prisoner not protected by the Geneva Conventions, because he was caught engaged in hostile action against the US while out of uniform and fighting for no constituted government. How difficult can this be?

I am concerned, because, as a libertarian conservative, I am quite certain that any government bureaucracy will usually cover its ass in preference to doing the morally right thing. (The American Revolution was largely fought against precisely this kind of abuse.) Is it possible that the Pentagon or some other government agency wants to keep this man imprisoned in order to hide their mistakes of thirteen years ago? I believe that to ask the question is to answer it.

This kind of issue is becoming more pressing instead of vanishing little by little because it looks like 9/11 what just the opening course. It looks like we are in this struggle against violent jihadism for the long run. Again, I am not proposing we go soft on terrorism. I worry that we are becoming used to government arbitrariness and mindless cruelty. I suspect that conservatives are often conflating their dislike of the president’s soft touch and indecision about terrorism with neglect of fairness and humanity. I fear we are becoming less American.

Let me ask again: What if this man, and some others in Guantanamo, have done absolutely nothing against us?

Of course, I hope the US will keep Guantanamo prison open as long as necessary. In fact, I expect fresh planeloads of real terrorist from Syria and Iraq to come in soon. I really hope that Congress will have the intestinal fortitude to call President Obama’s bluff on closing the prison. Congress has the means to stop it if it wants to.

Around the Web

- Political scientist Jason Sorens on the elections in Europe (best summary I’ve read; it’s short, sweet, and to the point)

- Examining Piketty’s data sources for US wealth inequality (Part 4 of 4)

- Greece the Establishment Clause: Clarence Thomas’s Church-State Originalism

- Strong Words and Large Letters

- The African Muslim Fist-Bump

- Why US Intervention in Nigeria is a Bad Idea