The most important historical question to help understand our rise from the muck to modern civilization is: how did we go from linear to exponential productivity growth? Let’s call that question “who started modernity?” People often look to the industrial revolution, which is certainly an acceleration of growth…but it is hard to say it caused the growth because it came centuries after the initial uptick. Historians also bring up the Renaissance, but this is also a mislead due to the ‘written bias’ of focusing on books, not actions; the Renaissance was more like the window dressing of the Venetian commercial revolution of the 11th and 12th centuries, which is in my opinion the answer to “who started modernity.” However, despite being the progenitors of modern capitalism (which is worth a blog in and of itself), Venice’s growth was localized and did not spread immediately across Europe; instead, Venice was the regional powerhouse who served as the example to copy. The Venetian model was also still proto-banking and proto-capitalism, with no centralized balance sheets, no widespread retail deposits, and a focus on Silk Road trade. Perhaps the next question is, “who spread modernity across Europe?” The answer to this question is far easier, and in fact can be centered to a huge degree around a single man, who was possibly the richest man of all time: Jakob Fugger.

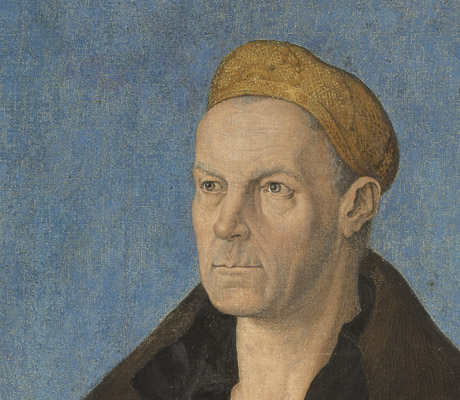

Jakob Fugger was born to a family of textile traders in Augsburg in the 15th century, and after training in Venice, revolutionized banking and trading–the foundations on which investment, comparative advantage, and growth were built–as well as relationships between commoners and aristocrats, the church’s view of usury, and even funded the exploration of the New World. He was the only banker alive who could call in a debt on the powerful Holy Roman Emperor, Charles V, mostly because Charles owed his power entirely to Fugger. Strangely, he is perhaps best known for his philanthropic innovations (founding the Fuggerei, which were some of the earliest recorded philanthropic housing projects and which are still in operation today); this should be easily outcompeted by:

- His introduction of double entry bookkeeping to the continent

- His invention of the consolidated balance sheet (bringing together the accounts of all branches of a family business)

- His invention of the newspaper as an investment-information tool

- His key role in the pope allowing usury (mostly because he was the pope’s banker)

- His transformation of Maximilian from a paper emperor with no funding, little land, and no power to a competitor for European domination

- His funding of early expeditions to bring spices back from Indonesia around the Cape of Good Hope

- His trusted position as the only banker who the Electors of the Holy Roman Empire would trust to fund the election of Charles V

- His complicated, mostly adversarial relationship with Martin Luther that shaped the Reformation and culminated in the German Peasant’s War, when Luther dropped his anti-capitalist rhetoric and Fugger-hating to join Fugger’s side in crushing a modern-era messianic figure

- His involvement in one of the earliest recorded anti-trust lawsuits (where the central argument was around the etymology of the word “monopoly”)

- His dissemination, for the first time, of trustworthy bank deposit services to the upper middle class

- His funding of the military revolution that rendered knights unnecessary and bankers and engineers essential

- His invention of the international joint venture in his Hungarian copper-mining dual-family investment, where marriages served in the place of stockholder agreements

- His 12% annualized return on investment over his entire life (beating index funds for almost 5 decades without the benefit of a public stock market), dying the richest man in history.

The story of Fugger’s family–the story, perhaps, of the rise of modernity–begins with a tax record of his family moving to Augsburg, with an interesting spelling of his name: “Fucker advenit” (Fugger has arrived). His family established a local textile-trading family business, and even managed to get a coat of arms (despite their peasant origins) by making clothes for a nobleman and forgiving his debt.

As the 7th of 7 sons, Jakob Fugger was given the least important trading post in the area by his older brothers; Salzburg, a tiny mountain town that was about to have a change in fortune when miners hit the most productive vein of silver ever found by Europeans until the Spanish found Potosi (the Silver Mountain) in Peru. He then began his commercial empire by taking a risk that no one else would.

Sigismund, the lord of Salzburg, was sitting on top of a silver mine, but still could not run a profit because he was trying to compete with the decadence of his neighbors. He took out loans to fund huge parties, and then to expand his power, made the strategic error of attacking Venice–the most powerful trading power of the era. This was in the era when sovereigns could void debts, or any contracts, within their realm without major consequences, so lending to nobles was a risky endeavor, especially without backing of a powerful noble to force repayment or address contract breach.

Because of this concern, no other merchant or banker would lend to Sigismund for this venture because sovereigns could so easily default on debts, but where others saw only risk, Fugger saw opportunity. He saw that Sigismund was short-sighted and would constantly need funds; he also saw that Sigismund would sign any contract to get the funds to attack Venice. Fugger fronted the money, collateralized by near-total control of Sigismund’s mines–if only he could enforce the contract.

Thus, the Fugger empire’s first major investment was in securing (1) a long-term, iterated credit arrangement with a sovereign who (2) had access to a rapidly-growing industry and was willing to trade its profits for access to credit (to fund cannons and parties, in his case).

What is notable about Fugger’s supposedly crazy risk is that, while it depended on enforcing a contract against a sovereign who could nullify it with a word, he still set himself up for a consistent, long-term benefit that could be squeezed from Sigismund so long as he continued to offer credit. This way, Sigismund could not nullify earlier contracts but instead recognized them in return for ongoing loan services; thus, Fugger solved this urge toward betrayal by iterating the prisoner’s dilemma of defaulting. He did not demand immediate repayment, but rather set up a consistent revenue stream and establishing Fugger as Sigismund’s crucial creditor. Sigismund kept wanting finer things–and kept borrowing from Fugger to get them, meaning he could not default on the original loan that gave Fugger control of the mines’ income. Fugger countered asymmetrical social relationships with asymmetric terms of the contract, and countered the desire for default with becoming essential.

Eventually, Fugger met Maximilian, a disheveled, religion-and-crown-obsessed nobleman who had been elected Holy Roman Emperor specifically because of his lack of power. The Electors wanted a paper emperor to keep freedom for their principalities; Maximilian was so weak that a small town once arrested and beat him for trying to impose a modest tax. Fugger, unlike others, saw opportunity because he recognized when aligning paper trails (contracts or election outcomes) with power relationships could align interests and set him up as the banker to emperors. When Maximilian came into conflict with Sigismund, Fugger refused any further loans to Sigismund, and Maximilian forced Sigismund to step down. Part of Sigismund’s surrender and Maximilian’s new treaty included recognizing Fugger’s ongoing rights over the Salzburg mines, a sure sign that Fugger had found a better patron and solidified his rights over the mine through his political maneuvering–by denying a loan to Sigismund and offering money instead to Maximilian. Once he had secured this cash cow, Fugger was certainly put in risky scenarios, but didn’t seek out risk, and saw consistent yearly returns of 8% for several decades followed by 16% in the last 15 years of his life.

From this point forward, Fugger was effectively the creditor to the Emperor throughout Maximilian’s life, and built a similar relationship: Maximilian paid for parties, military campaigns, and bought off Electors with Fugger funds. As more of Maximilian’s assets were collateralized, Fugger’s commercial empire grew; he gained not only access to silver but also property ownership. He was granted a range of fiefs, including Arnoldstein, a critical trade juncture where Austria, Italy, and Slovenia border each other; his manufacturing and trade led the town to be renamed, for generations, Fuggerau, or Place of Fugger.

These activities that depended on lending to sovereigns brings up a major question: How did Fugger get the money he lent to the Emperor? Early in his career, he noted that bank deposit services where branches were present in different cities was a huge boon to the rising middle-upper class; property owners and merchants did not have access to reliable deposit services, so Fugger created a network of small branches all offering deposits with low interest rates, but where he could grow his services based on the dependability of moving money and holding money for those near, but not among, society’s elites. This gave him a deep well of dispersed depositors, providing him stable and dependable capital for his lending to sovereigns and funding his expanding mining empire.

Unlike modern financial engineers, who seem to focus on creative ways to go deeper in debt, Fugger’s creativity was mostly in ways that he could offer credit; he was most powerful when he was the only reliable source of credit to a political actor. So long as the relationship was ongoing, default risk was mitigated, and through this Fugger could control the purse strings on a wide range of endeavors. For instance, early in their relationship (after Maximilian deposed Sigismund and as part of the arrangement made Fugger’s interest in the Salzburg mines more permanent), Maximilian wanted to march on Rome as Charlemagne reborn and demand that the pope personally crown him; he was rebuffed dozens of times not by his advisors, but by Fugger’s denial of credit to hire the requisite soldiers.

Fugger also innovated in information exchange. Because he had a broad trading and banking business, he stood to lose a great deal if a region had a sudden shock (like a run on his banks) or gain if new opportunities arose (like a shift in silver prices). He took advantage of the printing press–less than 40 years after Gutenberg, and in a period when most writing was religious–to create the first proto-newspaper, which he used to gather and disseminate investment-relevant news. Thus, while he operated a network of small branches, he vastly improved information flow among these nodes and also standardized and centralized their accounting (including making the first centralized/combined balance sheet).

With this broad base of depositors and a network of informants, Fugger proceeded to change how war was fought and redraw the maps of Europe. Military historians have discussed when the “military revolution” that shifted the weapons, organization, and scale of war for decades, often centering in on Swedish armies in the 1550s as the beginning of the revolution. I would counter-argue that the Swedes simply continued a trend that the continent had begun in the late 1400’s, where:

- Knights’ training became irrelevant, gunpowder took over

- Logistics and resource planning were professionalized

- Early mechanization of ship building and arms manufacturing, as well as mining, shifted war from labor-centric to a mix of labor and capital

- Multi-year campaigns were possible due to better information flow, funding, professional organization

- Armies, especially mercenary groups, ballooned in size

- Continental diplomacy became more centralized and legalistic

- Wars were fought by access to creditors more than access to trained men, because credit could multiply the recruitment/production for war far beyond tax receipts

Money mattered in war long before Fugger: Roman usurpers always took over the mints first and army Alexander showed how logistics and supply were more important than pure numbers. However, the 15th century saw a change where armies were about guns, mercenaries, technological development, and investment, and above all credit, and Fugger was the single most influential creditor of European wars. After a trade dispute with the aging Hanseatic League over their monopoly of key trading ports, Fugger manipulated the cities into betraying each other–culminating in a war where those funded by Fugger broke the monopolistic power of the League. Later, because he had a joint venture with a Hungarian copper miner, he pushed Charles V into an invasion of Hungary that resulted in the creation of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. These are but two of the examples of Fugger destroying political entities; every Habsburg war fought from the rise of Maximilian through Fugger’s death in 1527 was funded in part by Fugger, giving him the power of the purse over such seminal conflicts as the Italian Wars, where Charles V fought on the side of the Pope and Henry VIII against Francis I of France and Venice, culminating in a Habsburg victory.

Like the Rothschilds after him, Fugger gained hugely through a reputation for being ‘good for the money’; while other bankers did their best to take advantage of clients, he provided consistency and dependability. Like the Iron Bank of Braavos in Game of Thrones, Fugger was the dependable source for ambitious rulers–but with the constant threat of denying credit or even war against any defaulter. His central role in manipulating political affairs via his banking is well testified during the election of Charles V in 1519. The powerful kings of Europe– Francis I of France, Henry VIII of England, and Frederick III of Saxony all offered huge bribes to the Electors. Because these sums crossed half a million florins, the competition rapidly became one not for the interest of the Electors–but for the access to capital. The Electors actually stipulated that they would not take payment based on a loan from anyone except Fugger; since Fugger chose Charles, so did they.

Fugger also inspired great hatred by populists and religious activists; Martin Luther was a contemporary who called Fugger out by name as part of the problem with the papacy. The reason? Fugger was the personal banker to the Pope, who was pressured into rescinding the church’s previously negative view of usury. He also helped arrange the scheme to fund the construction of the new St. Peter’s basilica; in fact, half of the indulgence money that was putatively for the basilica was in fact to pay off the Pope’s huge existing debts to Fugger. Thus, to Luther, Fugger was greed incarnate, and Fugger’s name became best known to the common man not for his innovations but his connection to papal extravagance and greed. This culminated in the 1525 German Peasant’s War, which saw an even more radical Reformer and modern-day messianic figure lead hordes of hundreds of thousands to Fuggerau and many other fortified towns. Luther himself inveighed against these mobs for their radical demands, and Fugger’s funding brought swift military action that put an end to the war–but not the Reformation or the hatred of bankers, which would explode violently throughout the next 100 years in Germany.

This brings me to my comparison: Fugger against all of the great wealth creators in history. What makes him stand head and shoulders above the rest, to me, is that his contributions cross so many major facets of society: Like Rockefeller, he used accounting and technological innovations to expand the distribution of a commodity (silver or oil), and he was also one of the OG philanthropists. Like the Rothschilds’ development of the government bond market and reputation-driven trust, Fugger’s balance-sheet inventions and trusted name provided infrastructural improvement to the flow of capital, trust in banks, and the literal tracking of transactions. However, no other capitalist had as central of a role in religious change–both as the driving force behind allowing usury and as an anti-Reformation leader. Similarly, few other people had as great a role in the Age of Discovery: Fugger funded Portuguese spice traders in Indonesia, possibly bankrolled Magellan, and funded the expedition that founded Venezuela (named in honor of Venice, where he trained). Lastly, no other banker had as influential of a role in political affairs; from dismantling the Hanseatic League to deciding the election of 1519 to building the Habsburgs from paper emperors to the most powerful monarchs in Europe in two generations, Fugger was the puppeteer of Europe–and such an effective one that you have barely heard of him. Hence, Fugger was not only the greatest wealth creator in history but among the most influential people in the rise of modernity.

Fugger’s legacy can be seen in his balance sheet of 1527; he basically developed the method of using it for central management, its only liabilities were widespread deposits from the upper-middle class (and his asset-to-debt ratio was in the range of 7-to-1, leaving an astonishingly large amount of equity for his family), and every important leader on the continent was literally in his debt. It also showed him to have over 1 million florins in personal wealth, making him one of the world’s first recorded millionaires. The title of this post was adapted from a self-description written by Jakob himself as his epitaph. As my title shows, I think it is fairer to credit his wealth creation than his wealth accumulation, since he revolutionized multiple industries and changed the history of capitalism, trade, European politics, and Christianity, mostly in his contribution to the credit revolution. However, the man himself worked until the day he died and took great pride in being the richest man in history.

All information from The Richest Man Who Ever Lived. I strongly recommend reading it yourself–this is just a taster!