- The politics of “now” and the fall of the world’s governing soccer body David Runciman, London Review of Books

- Nineteenth-century rappers, Corn Laws, and the rise of free trade Greg Rosalsky, JSTOR Daily

- Avocados and tamales: language lessons Joyce Bartholomae, Coldnoon

- North Korea’s ice-cream-colored totalitarianism Lena Schipper, 1843

Ottomanism, Republicanism, Nationalism I

The Republican experiment in Turkey goes back formally to 1923, when Mustafa Kemal (later Kemal Atatürk) proclaimed the Republic of Turkey after the deposition of the last Ottoman Sultan, becoming the first President of the Republic after holding the office of Speaker of the National Assembly. The office of Caliph (commander of the faithful), which had a symbolic universalism for Muslim believers world wide and was held by the Ottoman dynasty, was abolished in the following year. The Republic, as you would expect in the early 20s, was founded on intensely nationalistic grounds, creating a nation for Turks distinct from the Ottoman system which was created in an era of religiously defined and personalised rule rather than ethnic-national belonging.

The move in a republican-national direction can be taken back to the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, which itself put down a counterrevolution in 1909, and might be taken as a model for current political divisions (in a qualified clarification through simplification manner). The name rather exaggerates the nationalist element of the revolution. The governments which came after 1908, ruling under an Ottoman dynasty reduced to a ceremonial role, were torn between Turkish nationalist, Ottomanist, and Islamist replacements for the personalised nature of Ottoman rule.

In this context Ottomanist refers to creating the idea of an Ottoman citizenship and shared institutions rather than restoring the political power of the dynasty. Variations on these ideas include Pan-Turkism/Turanism (the unity of Turkish peoples from the Great Wall of China to the Adriatic Sea) and a Dual Monarchy of Turks and Arabs modeled on the Habsburg Dual Monarchy of Austrians and Hungarians (that is the Habsburgs were Emperors of Austria in the Austrian lands and Kings of Hungary in the Magyar lands).

The move away from a patrimonial state based on the hereditary legitimacy of dynasties, who were not formally restricted by any laws or institutions, goes back to the Tanzimat edict of 1839, issued by Sultan Abdulmejid I in 1839, establishing administrative reforms and rights for Ottoman subjects of all religions. This might be taken as providing a model of moderate or even conservative constitutional reformism associated with the Young Ottoman thinkers and state servants. It has its roots in the reign of Mahmud II. Mahmud cleared the way for the reform process by the destruction of the Janissary Order, that is the military corps which had expanded into various areas of Ottoman life and was an important political force. The Tanzimat period led to the constitution and national assembly of 1876, which was suspended by Sultan Abdul II in 1878.

Abdul Hamit carried on with administrative reforms, of a centralised kind which were seen as compatible with his personal power, accompanied by war against rebellious Ottoman subjects of such a brutal kind that he became known as the Red Sultan. His status has been greatly elevated by President Erdoğan who evidently wishes to see himself as a follower of Abdul Hamit II, rather giving away his tendency to regard democracy and constitutionalism as adornments to be displayed when they can be bent and twisted to his end, rather than as intrinsic values. The brutality of Abdul Hamit II, the violent reactionary, was foreshadowed in the reformism of Mahmud II. His destruction of the arch-conservative corps of the Janissaries was a highly violent affair in which an Istanbul mutiny provoked by Mahmud was put down through the execution of prisoners who survived the general fighting.

In this sketch, I try to bring out the ways in which the Ottoman state used systematic violence to reform and to push back reform, when giving rights and when taking them away. There is no Ottoman constitutional tradition respecting the rights of all and the pre-republican changes were just as violent as the most extreme moments of the republican period.

The ‘millet system’ of self-governing religious communities under the Sultan was a retrospective idealisation of ways in which the Ottomans accommodated religious diversity, at the time the capacity of the state to have legitimacy over non-Muslim subjects was declining. Serbia started revolting in 1804, leading to self-government within the Empire in 1817, on the basis of national post-French Revolution, not the ‘millet’ tradition rooted in classical Muslim ideas of ‘protected’ minorities. The strength of modern nationalism in the Ottoman lands is confirmed by Greek Independence, internationally recognised in 1832, following a war in which western educated Greeks familiar with ideas of nationalism and sovereignty provided the ideology.

The republican national tradition in Turkey is sometimes seen as a fall away from Ottoman pluralism and therefore as regressive. The ‘regression’, as in the influence of nationalism and reconstruction of the Ottoman state through centralisation and centrally controlled violence, actually goes back much further. The Ottoman state was not able to find ways of accommodating the aspirations first of non-Muslim subjects then even of Muslim subjects outside Anatolia and Thrace. In this process the Ottoman state was step by step becoming what is now Turkey, based on the loyalty of mostly ethnic Turkish subjects, including Muslim refugees from break-away states who fled into Anatolia, and to some degree on the loyalty of Kurds in Anatolia to the Ottoman system. Antagonism towards Ottoman Armenians was one part of this.

To be continued

Nightcap

- What caused the Black Death and could it strike again? Wendy Orent, Aeon

- Which cities have people-watching street cafes? Tyler Cowen, Marginal Revolution

- Keenan’s view of the Far East Francis Sempa, Asian Review of Books

- Is neoliberalism dead? Scott Sumner, EconLog

Nightcap

- The illiberal conception of freedom Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

- The echoes of Chinese exclusion (immigration) Irene Hsu, New Republic

- The Middle Kingdom: all under heaven? George Walden, American Interest

- Have we forgotten how to die? Julie-Marie Strange, Times Literary Supplement

Law, Judgement, Republicanism

Draft material for a joint conference paper/Work in Progress on a long term project

This paper comes out of a long term project to work on ideas of liberty in relation to republicanism in political thought, along with issues of law and sovereignty. The paper in question here comes out of collaborative work on questions of law, judgement, and republicanism in relation to Turkey’s history and its current politics. Though this comes from collaborative work, I take sole responsibility for this iteration of draft material towards a joint conference paper, drafted with the needs of a blog with a broad audience in mind.

The starting point is in Immanuel Kant with regard to his view of law and judgement. His jurisprudence, mostly to be found in the first part of the Metaphysics of Morals on ‘The Doctrine of Right’, is that of law based on morality, so is an alternative to legal positivism. The argument here is not to take his explicit jurisprudence as the foundation of legal philosophy. There is another way of looking at Kant’s jurisprudence which will be discussed soon.

What is particularly valuable at this point is that Kant suggests an alternative to legal positivism and the Utilitarian ethics with which is has affinities, particularly in Jeremy Bentham. Legal positivism refers to a position in which laws are commands understood only as commands, with regard to some broader principles of justice. It is historically rooted in the idea of the political sovereign as the author of laws. Historically such a way of thinking about law was embedded in what is known to us as natural law, that is, ideas of universal rules of justice. This began with a very sacralised view of law as coming from the cosmos and divine, in which the sovereign is part of the divinely ordained laws. Over time this conception develops more into the idea of law as an autonomous institution resting on sovereign will. Positivism develops from such an idea of legal sovereignty, leaving no impediment to the sovereign will.

Kant’s understanding of morality leaves law rooted in ideas of rationality, universality, human community, autonomy, and individual ends which are central to Kant’s moral philosophy. The critique of legal positivism is necessary to understanding law in relation to politics and citizenship in ways which don’t leave a sovereign will with unlimited power over law. Kant’s view of judgement suggests a way of taking Kant’s morality and jurisprudence out of the idealist abstraction he tends towards. His philosophy of judgement can be found in the Critique of Judgement Power, divided into parts on aesthetic judgments of beauty and teleological judgments of nature.

The important aspect here is the aesthetic judgement, given political significance through the interpretation of Hannah Arendt. From Arendt we can take an understanding of Kant’s attempts at a moral basis for law, something that takes political judgement as an autonomous, though related, area. On this basis it can be said that the judgement necessary for there to be legal process, bringing particular cases under a universal rule, according to a non-deterministic subjective activity, on the model of Kant’s aesthetic judgement is at the root of politics.

Politics is a process of public judgement about particular cases in relation to the moral principles at the basis of politics. The making of laws is at the centre of the political process and the application of law in court should also have a public aspect. We can see a model of a kind in antiquity with regard to the minor citizen assembly, selected by lottery, serving as a jury in the law courts of ancient Athens. It is Roman law that tends to impose a state oriented view of law, in which the will of the sovereign is applied in a very absolutist way, so that in the end the Emperor is highest law maker and highest judge of the laws.

As Michel Foucault argues, and Montesquieu before him, the German tribes which took over Roman lands had more communal and less rigidly defined forms of court judgement, and were more concerned with negotiating social peace than applying laws rigidly to cases. Foucault showed how law always has some political significance with regard to the ways in which sovereignty works and power is felt. That is the law and the work of the courts is a demonstration of sovereignty, while punishment is concerned with the ways that sovereignty is embedded in power, and how that power is exercised on the body to form a kind of model subjugation to sovereignty. The Foucauldian perspective should not be one in which everything to do with the laws, the courts, and methods of punishment is an expression of politics narrowly understood.

The point is to understand sovereignty as whole, including the inseparability of institutions of justice from the political state. The accountability of the state and the accountability of justice must be taken together. Both should work in the context of public accessibility and public discussion. The ways in which laws, courts, and judges can be accountable to ideas of autonomy must be declared and debate. Courts should be understood as ways of addressing social harms and finding reconciliation rather than as the imposition of state-centric declarations of law.

Should The Academic “We” Be Ditched?

“Only kings, presidents, editors, and people with tapeworms have the right to use the editorial ‘we’.” – Mark Twain

When writing academically I use the “we” pronoun. I do so for a variety of reasons, but I am starting to rethink this practice. This may seem like a silly topic, but a quick google shows that I’m not the only one who thinks about this: link 1, link 2.

My K-12 teachers, and even my undergraduate English professor, constantly told me that I was prone to writing in a stream of consciousness. My writing, they argued, contained too much of my personality. They pointed out my constant use of “I”s of example of this. I I was, in general, an awful English student. In 12+ years of schooling, I rarely used the five page paragraph structure that American school children are indoctrinated with. I first adopted the use of the academic “we” in an attempt to force myself to distinguish between personal forms of writing, such as when I write on blogs, where these eccentricities could be tolerated and technical writing.

While that was my initial motivation for using the “we”, I also found the pronoun a way to emphasize the collaborative nature of science. I have several single authored papers, but I would be lying if I said that any of them were developed in a vacuum divorced from other’s feedback. Getting feedback at a conference or brown bag workshop may not merit including someone as a co-author, but I feel it strange to use “I” academically in this context. For anyone who disagrees with me – I ask that you compare a paper before and after submitting it to the review process. One may hate reviewer #2 for insisting on using an obscure estimation technique, but it cannot be denied that they shaped the final version of the paper. Again, I’m not saying we should add reviewers as co-authors, but isn’t using ‘we’ a simple way of acknowledging their role in the scientific process?

I admit, I also enjoy using the academic “we” in part because of its regal connections. King Michelangelo has a nice ring to it, no?

There are downsides to the use of the academic “we”. On several occasions I’ve had to clarify that I was the sole author of a given paper. What do NOL readers think? Do you use the academic “we”?

#microblog

Some quick thoughts from Athens

I spent the last week and a half in Greece (mainly Athens and other historical sites in the Peloponnese) thanks to the Reason, Individualism and Freedom Institute, and explored ancient political philosophy in a modernly turbulent state. I’m writing this in Naples. Here are a few thoughts I had from the first couple days in Athens.

There is a strong antifa presence (at least judging from graffiti, small talk with some locals and the bios of Grecian Tinder girls). I can’t help but imagine the American antifa pales in comparison. Our black bloc — thrust into the spotlight in mostly superficial college campus debates — tends to be enthusiastic, whereas the antifa in Hellas, culturally sensitive to millennia of dictatorships, entrenched aristocracies, Ottoman annexation, great power puppeteering and a century of neighbouring fascist regimes, must be somber and steadfast. Our antifa crowd has so little targets to find Ben Shapiro a worthy protest, whereas Golden Dawn, the ultranationalist, Third Reich-aesthetics Metaxist party gets 7% in the Hellenic Parliament. Nothing here is spectacle. (Moreover, the extreme-right in Greece, according to our tour guide, has been known to worship and deify mainstream Christian figures as well as the ancient gods spawned of Uranus and Gaia. Umberto Eco’s immortal essay Ur-Fascism explained phenomena like this as the ‘syncretic’ element of fascist traditionalism.)

Moving past the fascists and antifa, in general Greece is left. The Communist Party of Greece, KKE, gets about 5% of the votes and displays a sickle and hammer. More telling still, plenty of the leftist graffiti is actually representing the KKE. Political parties tend to de-radicalize, or are supposed to in theory, and the fringe ideologues disavow the party for centrism or weakness (it’s funny to think of American socialists spray-painting the initials of the CPUSA). The graffiti stretches all the way to Lesvos, of Aristotle’s biology and Sappho’s poetry, and to Corinth of the cult of Aphrodite, but is most prominent in downtown Athens.

Athens has an anarcho-friendly district with a rich history called Εξάρχεια, Exarcheia. Antifascist tagging is complimented by antipolice, antistate, antiborders and LGBT designs, the Macedonian question is totally absent, and posters about political prisoners stack on each other like hotels on ruins. Our friends at KEFiM warned us about Exarcheia — it has a history of political/national xenophobia, and one member had been violently assaulted — but I had already visited on the first day. Aside from a recently blown-up car, it wasn’t too different from Berkeley — nice apartments and restaurants juxtaposed with street art and a punk crowd, drug dealing, metal bars on windows. Granted, this was in daylight and I saw only what was discoverable with Google maps. Still, I had the fading remains of a black eye and my usual clothing is streetwear, so maybe I wasn’t too out of place — even as an American and thus most hated representative of that target of so much antifascist graffiti, NATO.

Much of the larger politics of Greece were not easy to discover from our various tour guides. Just like the ancient myths of the country, they constantly contradict each other.

The Athens underground metro was incredibly clean and modern — infinitely more than in Atlanta, San Francisco, Los Angeles, etc. — while their roads are constipated and chaotic. Duh, the city itself is one of our most ancient settled, and so roads have proceeded in a particularly unorganized fashion. But it did cause me to consider the beauty that on a planet where our civilizations literally build on each other generation after generation — and, in an uncommon historical epoch where conquering is out of fashion — sometimes the only place to go is down. Humans have expanded our surface area in dimensions completely unfathomable to the diasporic colonizers from ancient Crete.

The syncretic chaos of the streets, though nauseating to the newcomer, lends itself to almost divine levels of flânerie, such that one can walk hours without reaching any particular destination and feel accomplished. Nothing much looks the same when Times Square melts into an ancient agora melts into a Byzantine church melts into the beach. Attica is wildly heterogeneous and beautiful; modernist adherents to classical Greek conceptions of precision-as-beauty should be humbled.

I should add also that my first impressions of Athens (and Catania) was how much it looked like something out of a videogame. The condition of 21st century man is that, upon visiting foreign cities for the first time, he will invariably compare them to Call of Duty maps.

On a few occasions, enough for me to notice but not enough for me to declare it a custom, my server (who sits me, takes my order and waits on me) gave me extra food on the side. This only happened at small restaurants that aren’t overly European and might be an orange juice, fruit bowl or something small and similar. Every time, of course, I left a larger tip. These actions put us in a sort of gamble. For the waiter to bring me something periphery, he might expect a grander gratuity. Then, when I notice the extra item, I have to assume that it’s not just a mistake — that he didn’t think I ordered something extra which will appear on my tab. He and I are both sort of gambling our luck. Of course, it’s not a real gamble — in every instance we were at least partially sociable prior and lose nothing substantial if it doesn’t work out. What is interesting is that we’ve removed ourselves just a little from the law — I am only legally obligated to pay for what I ordered; he is only legally obliged to bring me what I paid for. Still, without the legal backdrop, everyone leaves happy. Left-libertarians would like it.

(As everyone knows, the Greeks are very hospitable and friendly, and this is a testament to that. A counter-example: I went to a gay club for the first time in the rainbow district of Athens. I can’t speak enough of the tongue to talk to women anyway, and there is at least a chance that some guy will buy us drinks. Nobody buys us drinks. The only conclusions are that we’re not handsome enough or the Greeks are not as friendly. It has to be the latter.)

I should quickly add something about coffee. Where it not for the drought of drip coffee, I could easily stay in the Mediterranean forever. Alas, to literally order an “iced coffee” — kafe frappe — you are ordering a foamy concoction with Nescafé. To order a Greek coffee (known as a “Turkish coffee” before tensions in the 1960’s) means an espresso-type shot with grounds/mud at the bottom. But, the coffee culture is fantastic — the shops are all populated with middle-aged dudes playing cards, smoking rollies, and shooting the shit. I don’t think I need to describe the abominable state of American coffee culture. Entrenched in their mud, the Greeks resisted American caffeine imperialism. Starbucks tried and failed to conquer the coffee market: there were already too many formulas, and the Greeks insisted on smoking inside.

Nightcap

- Abu Raihan al-Biruni, an Islamic scholar from Central Asia, may have discovered the New World centuries before Columbus S. Frederick Starr, History Today

- Gendun Chopel: Tibet’s Modern Buddhist Visionary John Butler, Asian Review of Books

- Toru Dutt’s strangeness from India and the French Revolution Blake Smith, Coldnoon

- Singapore in translation Theophilus Kwek, Times Literary Supplement

Nightcap

- The road to nowhere: Manbij, Turkey, and America’s dilemma in Syria Aaron Stein, War on the Rocks

- The U.S. and Turkey Scott Sumner, EconLog

- The Kurdish issue in Turkey Barry Stocker, NOL

- Is nationalism obsolete? Rachel Lu, the Week

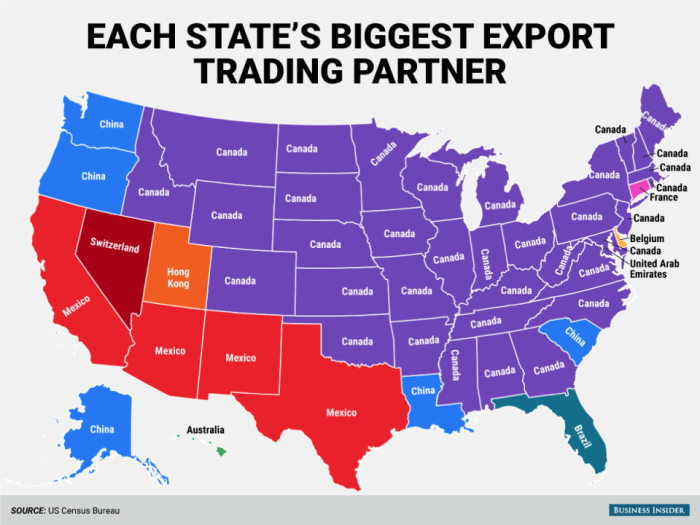

Eye Candy: Each (American) state’s biggest export trading partner

Those tariffs will work wonders for the economy, I’m sure…

Nightcap

- Roosevelt, Taft, and the Nasty 1912 GOP Convention Rick Brownell, Historiat

- In praise of (occasional) bad manners Freya Johnston, Prospect

- What Should America Expect from a More Originalist Supreme Court? David French, National Review

- Why ultra-nationalists exceeded expectations in Turkey’s elections Pinar Tremblay, Al-Monitor

Pakistan’s dynastic politics and the PML-N’s Sharif family

As in other parts of South Asia, dynastic politics is an integral feature of Pakistan’s politics. Both the PPP (Pakistan People’s Party) and the PML-N (Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz) are essentially family-run political parties. While the PPP has been dominated by the Bhutto family, the PML-N has been dominated by the Sharif family.

Resentment against family domination in PML-N

In the recent past, there has been resentment against the rise of both Maryam Nawaz Sharif (daughter of former Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif) and Hamza Shehbaz, son of Shehbaz Sharif (PML-N party chief and younger brother of Nawaz Sharif).

The latest resignation from PML-N was that of Zaeem Qadri, once a confidante of Shehbaz Sharif, who was denied a seat for the NA-133 (an electoral constituency in Pakistan). Qadri used some harsh words for Hamza Shahbaz, saying ‘Hear Hamza Shahbaz! Lahore is neither your, nor your father’s property.’ Qadri also stated, that one of the reasons he did not get the ticket was that he did not possess adequate resources.

In the run up to the elections, internal dynamics of the PML-N, as well as the role of the Pakistan military, will be crucial (it has been lending tacit support to the opposition, to weaken the PML-N, especially in the party’s citadel of Punjab).

Dynastic politics and differences within the Sharif family

If one were to look at the resentment against Maryam Nawaz, only last year, Chaudhry Nisar, former Interior Minister, who does not share particularly cordial relations with the Sharifs, said that it is too premature to compare Maryam Nawaz with Benazir Bhutto. Said Nisar in an interview with Geo TV:

Comparing Maryam Nawaz to Benazir Bhutto is wrong […] Maryam Nawaz should understand and partake in practical politics. Only then can she be considered a leader.

Another minister, Saad Rafique, too had stated that Maryam Nawaz should be ‘cautious while addressing public meetings.’

Rivalry between Hamza Shehbaz and Maryam Nawaz

It has been argued that one of the main reasons for the strained relationship between Shahbaz Sharif and Nawaz Sharif was the rivalry between their children. After Nawaz was removed from Prime Ministership in July 2017, one of the reasons why Shahbaz (now the PM candidate) was not immediately appointed interim Prime Minister, as well as President of the PML-N, was that there was a clamor for Hamza Shahbaz as Chief Minister of Punjab and Nawaz’s family was not comfortable with an arrangement where both father and son would be powerful. Later on, Nawaz appointed Pervez Malik, instead of Hamza Shehbaz, as campaigner in charge for NA-120, which was fought by his wife Kulsoom Nawaz.

Military’s behind the scenes manuevres and defections

In recent months, the Pakistan army has been trying to engineer a number of defections from the PML-N to PTI, and even though the military shares a comfortable relationship with Shehbaz, as compared to Nawaz, it is believed that now they would be most comfortable with Imran Khan as PM. There have also been reports of the military not just arm twisting political leaders of the PML-N, but censoring the media as well. Whether the latest resignation was prompted by the military is in the realm of speculation of course.

The Army and Nawaz’ reaction to the resignation of Qadri

Interestingly, Qadri’s resignation may be welcomed not just by the military, since it would have come across as a setback to the PML-N, which is considered the dominant force in Punjab. In his heart of hearts, Shahbaz’ brother Nawaz too may not mind this, since it will not only clip Hamza’s wings but also weaken Shahbaz’ position to some extent. During his press conference, Qadri made a mention of Nawaz Sharif, saying that the Former PM had told Qadri that many within the PML-N were not happy with his presence in the party.

While the two brothers share a very strong rapport, in spite of temperamental differences in the past year, there has been a degree of friction. After Nawaz’ remarks on the Mumbai attacks, where he blamed Pakistan for delaying the trial of the accused, Shahbaz had to intervene, and apparently told Nawaz not to talk to the press without consulting Shehbaz. In an interview to the Dawn newspaper, Nawaz had said:

Militant organisations are active. Call them non-state actors, should we allow them to cross the border and kill 150 people in Mumbai? Explain it to me […] Why can’t we complete the trial?

In spite of the differences within the PML-N, and some tensions between both brothers, there is a strong realization that the main crowd puller for the PML-N still remains Nawaz Sharif, and with the elder Sharif being in London due to his wife’s ill health (she has been on ventilator since June 14 2018) it is unlikely that he will be able to spearhead the campaign.

On the whole, defections like Qadri’s are not likely to have much of an impact on the prospects of the PML-N, given Nawaz’ charisma and goodwill, along with the fact that he is looked at as an individual who has taken on the army, and Shahbaz Sharif’s performance as Chief Minister. What will really be crucial is the success of the Pakistan military’s back door machinations, and to what extent will it go all out to back PTI Chief Imran Khan, who himself has been in the eye of a storm after a book written by his former wife and senior journalist, Reham Khan, has made some serious accusations against him, and could dent his prospects amongst certain sections.

Conclusion

It is in Pakistan’s interest that the 2019 election verdict results in the strengthening of the democratic set up. Apart from a dire need for change in the military’s mindset, political parties in Pakistan (like in other South Asian countries) too need to get their house in order and move beyond being family concerns. It is also important to have greater intraparty democracy.

Turkey after the Election

Grim Facts

Turkey held National Assembly and Presidential elections last Sunday (24th June). Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan won an overall majority of votes and retained the presidency without a second round of voting. The pro-Erdoğan electoral list of his AKP (Justice and Development Party/Adelet ve Kalkınma Partisi) and the older (the second oldest party in Turkey) but smaller MHP (Milliyetçi Hareket Partisi/Nationalist Action Party) took a majority of votes. The MHP took more votes than the breakaway Good Party (İYİ Parti/IP), though IP’s leader (Meral Akşener) is more popular than the MHP leader (Devlet Bahçeli) and the IP has more members.

The MHP broke through the 10% barrier to entry into the National Assembly in the votes cast for it, within the joint electoral list, though it was mostly expected to fall short by a distinct margin. Since the more moderate elements of the MHP joined IP, MHP forms part of a presidential majority in the National Assembly, with its authoritarian monolithic variety of nationalism unrestrained.

The main opposition party, the Republican People’s Party (Cumhuriyet Halk Partisi/CHP, a centre left and secularist-republican party), lost about one tenth of its National Assembly votes. The third party in the opposition electoral list, SP (Saadet Partisi/Felicity Party), a religious conservative party with the same roots as AKP, failed to get up to 1% in either the presidential or National Assembly elections, thus failing to increase its vote significantly and failing to take any notable fraction of the AKP vote.

CHP and then IP leaders failed to live up to promises to demonstrate outside the Supreme Election Council building in Turkey to protest against likely electoral rigging. Opposition data on voting gathered by election monitors ended up almost entirely coinciding with ‘official’ results (strictly speaking official results will not be available until 5th July) and earlier information is preliminary only.

Qualification of Grim Facts

The above gives the bare facts about the results with regard to the most disappointing aspects from the point of view of the opposition. This is a disappointing result for anyone opposed to the authoritarian regime of Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan, which began by appealing to supporters of reform in a country with rather limited liberalism in its democracy.

Erdoğan has since made it clear that he regards democracy as the unlimited power of one man who claims to represent the People against liberal, westernised, secularist, and leftist ‘elites’ and ‘marginals’, along with foreign and foreign manipulated conspiracies against the Nation.

One qualification to the bad news above is that the opposition during the election is fighting against bias, exclusion, threatening accusations, harassment, violence and legal persecution from the state apparatus, state media, private media effectively under state direction (which is most of the private media), and gangs of thugs, some armed. At the very least the opposition held its ground in terrible circumstances, which have been getting continuously worse for years.

Another ‘optimistic’ aspect is that while there was certainly some vote rigging of a kind it was difficult for opposition monitors to capture. This includes pre-marked voting ballots. As in last year’s referendum vote, videos of pre-marking of ballots have been circulating on social media.

In the referendum campaign the electoral authorities broke the law by accepting ballot papers which had not been stamped by a polling station official. This was legalised in time for the election and broadened to allow counting of ballot papers in unstamped envelopes.

Legal changes have also made it easier for state authorities to move polling stations and remove ballot boxes from polling stations to be counted elsewhere. On a less official level, reports indicate harassment of voters by armed gangs and some employers requiring evidence from a phone camera photograph of voting for the government.

There have been problems for decades with polling stations (especially in areas where the opposition does not send monitors because of a small local base) ignoring opposition votes and recording ‘100%’ for the party in control of the state at the time.

It is very difficult to know what the overall number of votes is changed by these malpractices. It is, however, clear that the southeast of the country (that is the Kurdish majority region) is much more vulnerable to such practices because of the atmosphere created by PKK (far left Kurdish autonomy terrorist/insurgent group) and the security-state counter operations.

The main Kurdish identity party, the leftist HDP (Halkların Demokratik Partisi/Peoples’ Democratic Party), competes with the AKP for first place in the southeast. It is regularly accused of supporting PKK terrorism and even of being an organic part of the PKK in government oriented media and legal cases opened by highly politicised state prosecutors.

There is certainly overlap between PKK sympathisers and HDP supporters, but ‘evidence’ that the HDP supports terrorism consists of statements calling for peace, criticising security operations against the PKK and it’s Syrian partner (PYD), and criticising state policy towards the PKK. Whatever one might think of the HDP’s policies and statements, these are not evidence that it is a terrorist organisation. The idea that it is legitimises official harassment (including imprisonment) and less officials forms of intimidation and vote rigging. It also legitimises less widespread but very real harassment of the CHP on the grounds that some supporters voted HDP to get is past the 10% thresh hold and, in a limited and very moderate way, the CHP has expressed some sympathy for persecuted HDP leaders and activists.

I can only make guesses but I think it is reasonable to estimate that 1% of votes have been historically manipulated and that this has increased along with the strengthening grip of the AKP on the state and parts of civil society, and also with its increasing demonisation of opposition.

I’ll estimate 3% for the votes manipulated.

Election evening results indicated just over 53% for Erdoğan as president and for the electoral list backing him. This has however been going down as later ‘preliminary’ results so it may now be about 52% for both votes. In this case, if 3% of votes are manipulated (a very sober estimate in my view) then we could be looking at 49% for Erdoğan and his supporters. This might still give a slight majority in the National Assembly, as distribution of seats is biased towards rural and small town conservative areas, and since 100% of votes are not represented by seats in the National Assembly in even the most pure form of proportional representation (because there are always some micro-parties which get some votes but do not enter the National Assembly).

A run-off for president after Erdoğan gets 49% seems very likely to still set up Erdoğan as the winner in the second round. It is of course wrong in principle to rig at this level but it doesn’t change anything important presuming rigging is at the level I’ve suggested. I will have a clearer idea about this when all results are officially released on 5th July.

On further relatively good news, the CHP vote in the presidential election was at 30%, about one fifth higher than before.

The presidential candidate Muharrem İnce turned out to be an inspiring campaigner and public speaker able to appeal to a variety of sections of Turkish society. He seems like a natural fit for the leadership of CHP, though so far the incumbent, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu has been slow to step down and clear the way.,

The final results seem likely to show at least a slight decline for Erdoğan since the 2014 presidential election. IP is new and has no local government base. As there are local elections at the end of March next year, they should be able to establish local strongholds and build on that nationally.

The AKP does not have a majority in the National Assembly for the first time since 2002. MHP makes up the majority at present and as stated above seems likely to behave in a very nationalist-authoritarian way. However, its vote seems to have been increased by disaffected AKP voters (particularly in the southeast) who are not ready, so far, to vote against Erdoğan and a pro-Erdoğan electoral list. This makes their support rather unstable and the MHP is likely to see advantage in turning away from Erdoğan at some point, or at least cause him trouble by asserting its independence. Erdoğan is not someone to welcome, or live with, this kind of division in his support bloc and a conflict of some kind seems likely at some point.

Nightcap

- Centrists against freedom Chris Dillow, Stumbling and Mumbling

- Civility and Property vs. Politics Jeff Deist, Power & Market

- Justice Kennedy Retires, and the Legal and Political Ramifications Are Immense David French, the Corner

- Religious Bric-à-Brac and Tolerance of Violent Jihad Jacques Delacroix, Liberty Unbound

Busy, busy, busy

Hey folks, I’ve been busy. I just moved from Austin to Waco, and found out child #2 is on the way. Holy crap!

Here is my Tuesday column at RealClearHistory, on Rod Blagojevich, and here is my weekend column for the same site, on the World Cup. Be sure to check them out! I’ve got two columns per week at RealClearHistory, one comes out Tuesdays and the other on Fridays.

I hope you’ve been enjoying yourselves here at NOL. Awhile back, Michelangelo suggested I shift more of my writing focus here to be on libertarian parenting, but I thought that might be a bit too personal. (There’s a lot of weirdos out there.)

I’ve invited Joakim, Shree, Ethan, and Mary to join us at the consortium, and I do hope you’ve been enjoying their stuff so far (I know I have). You can find out what everyone has been up to lately by starting here (or here, if you’re on Twitter).

Have a good weekend!