- Examining the state of German identity Sebastian Hammelehle, Der Spiegel

- Tadao’s war memory manga Ryan Holmberg, NY Review of Books

- The Buddhist monk who became an apostle for sexual freedom Donald Lopez, Aeon

- Denmark’s most innovative city Simon Willis, 1843

RCH: the Peace of Paris (1783)

My latest at RealClearHistory is up. An excerpt:

The Americans did not like this proposal one bit, and they went around the French and their Spanish allies and negotiated a separate treaty with the British, who were all too happy to give up some land in exchange for sticking a thumb in France’s eye. The French foreign minister at the time of the treaty negotiations, Charles Gravier, Count of Vergennes, bitterly complained that “the English buy peace rather than make it.” London also anticipated a rapprochement between itself and its now-former colonies, and a favorable treaty with the rebels would buy the British some much-needed diplomatic capital down the road. The American diplomats who negotiated such a generous truce were led by Benjamin Franklin, John Jay, and John Adams.

Please, read the rest.

LARB can’t figure out why South Korea’s government is so bad at marketing campaigns

Colin Marshall is a blogger for the Los Angeles Review of Books (LARB), a great publication that has featured NOL‘s own Barry Stocker before. Marshall is puzzled by the fact that Seoul’s best marketing comes from independent filmmakers rather than the South Korean government. I guess I shouldn’t say “puzzled” because Marshall has a theory as to what is to blame, but I thought the piece was interesting because it highlights so well why libertarianism is so important.

Here is a link to Marshall’s piece. It is filled with lamentations about the Korean government’s inability to produce good marketing for the country. Instead of going for the jugular, though, and pointing out that incentives matter, here is where Marshall pins the blame:

I often wonder whether the problem has to do with the difficulty Koreans have in seeing Korea clearly, at least when looking for its good points; when dwelling on the negative, they suffer from no such lack of perceptual acumen. Many an acquaintance here has asked me, indeed insisted I reveal to them, what displeases me about Korea. For years I didn’t have a straight answer, but then I realized that nothing bothers me quite so much as Korea’s culture of complaint itself.

Got that? Marshall is wondering aloud (blaming) Korean culture for the bland marketing campaigns of the Korean government, even though he recognizes the brilliant marketing campaign of the independent filmmaker in the beginning of his piece. Not only does he blame Koreans for a problem that affects all governments, he attacks the “culture of complaint” that Koreans are well-known for.

Complaining, critiquing, one’s culture is a necessary component for a free and open society (Chhay Lin wrote about this at NOL awhile back, regarding Cambodia).

Am I engaging in bad faith here? Is Marshall really that ignorant of markets and alternative orders that he fails to understand why the Korean government cannot produce anything creative? Is Marshall so stupefied by the predictable failure of the Korean government to produce anything creative that he would stoop to insulting his hosts? Help me out here, folks.

Nightcap

- ISIS never went away in Iraq Krishnadev Calamur, the Atlantic

- In search of “real” socialism Kristian Niemietz, CapX

- Localism and its trade-offs Jason Sorens, Law & Liberty

- Latin America’s greatest storyteller Thomas Meany, Claremont Review of Books

RCH: 10 rivalries that shaped world history

My weekend column for RealClearHistory, in case you missed it, was fun to write. An excerpt:

4. The Mughals versus the Persians (1600s -1739). The Mughal Empire, an Indian polity that ruled over much of the subcontinent, fought three wars against two Persian dynasties (Safavids and Afsharids) and lost all of them. Much of the fighting was done around the city of Kandahar, in what is now Afghanistan. Kandahar was for a long time an important fortress for empires and dynasties that lorded over both Persia and India. While the Mughals had their pride stung by the losses, they could at least find solace in the fact their realm was the most economically successful on the planet at the time. India and Iran have long been weary regional rivals and sometime allies, but geographic distance and terrain have made outright wars between the two civilizations rare and limited. The rivalry between Iran and India has been a cultural one rather than a military one.

Read the rest (if you haven’t already!).

Are Swedish University Tuitions Fees Really Free?

University tuition fees are always popular talking points in politics, media, and over family dinner tables: higher education is some kind of right; it’s life-changing for the individual and super-beneficial for society, thus governments ought to pay for them on economic as well as equity grounds (please read with sarcasm). In general, the arguments for entirely government-funded universities is popular way beyond the Bernie Sanders wing of American politics. It’s a heated debate in the UK and Australia, whose universities typically charge students tuition fees, and a no-brainer in most Scandinavian countries, whose universities have long had up-front tuition fees of zero.

Many people in the English-speaking world idolize Scandinavia, always selectively and always for the wrong reasons. One example is the university-aged cohort enviously drooling over Sweden’s generous support for students in higher education and, naturally, its tradition of not charging tuition fees even for top universities. These people are seldom as well informed about what it actually means – or that costs of attending university is probably lower in both England and Australia. Let me show you some vital differences between these three countries, and thereby shedding some much-needed light on the shallow debate over tution fees:

The entire idea with university education is that it pays off – not just socially, but economically – from the individual’s point of view: better jobs, higher lifetime earnings or lower risks of unemployment (there’s some dispute here, and insofar as it ever existed, the wage premium from a university degree has definitely shrunk over the last decades). The bottom line remains: if a university education increases your lifetime earnings and thus acts as an investment that yield individual benefits down the line, then individuals can appropriately and equitably finance that investment with debt. As an individual you have the financial means to pay back your loan with interest; as a lender, you have a market to earn money – neither of which is much different from, say, a small business borrowing money to invest and build-up his business. This is not controversial, and indeed naturally follows from the very common sense principle that those who enjoy the benefits ought to at least contribute towards its costs.

Another general reason for why we wouldn’t want to artificially price a service such as university education at zero is strictly economical; it bumps up demand above what is economically-warranted. University educations are scarce economic goods with all the properties we’re normally concerned about (has an opportunity cost in its use of rivalrous resources, with benefits accruing primarily to the individuals involved in the transaction), the use and distribution of which needs to be subject to the same market-test as every other good. Prices serve a socially-beneficial purpose, and that mechanism applies even in sectors people mistakenly believe to be public or social, access to which forms some kind of special “human right.”

From a political or social-justice point of view, such arguments tend to carry very little weight, which is why the funding-side matters so much. Because of debt-aversion or cultural reasons, lower socioeconomic stratas of societies tend not to go to university as much as progressives want them to – scrapping tuition fees thus seems like a benefit to those sectors of society. When the financing of those fees come out of general taxation however, they can easily turn regressive in their correct economic meaning, disproportionately benefiting those well off rather than the poor and under-privileged they intended to help:

The idea that graduates should make no contribution towards the tertiary education they will significantly benefit from it, while expecting the minimum wage hairdresser in Hull, or waiter in Wokingham to pick up the bill by paying higher taxes (or that their unborn children and grandchildren should have to pay them due to higher borrowing) is highly regressive.

Although not nearly enough people say it, university is not for everyone. The price tag confronts students, who perhaps would go to university to fulfill an expectation rather than for any wider economic or societal benefit, with a cost as well as a benefit of attending university.

Having said that, I suggest that attending university is probably more expensive in your utopian Sweden than in England or Australia. The two models these three countries have set up look very different at first: in Sweden the government pays the tuition and subsidies your studies; in England and Australia you have to take out debt in order to cover tuition fees. A cost is always bigger than no cost – how can I claim the reverse?

With the following provision: Australian and English students don’t have to pay back their debts until they earn above a certain income level (UK: £18,330; Australia: $55,874). That is, those students whose yearly earnings never reach these levels will have their university degree paid for by the government regardless. That means that the Scandinavian and Anglophone models are almost identical: no or low costs accrue for students today, in exchange for higher costs in the future provided you earn enough income. Clearly, paying additional income taxes when earning high incomes but not on low incomes (Sweden) or paying back my student debt to the government only if I earn high incomes rather than low (England, Australia) amounts to the same thing. Changing the label of a financial transfer from the individual to the government from “debt-repayment” to “tax” has very little meaning in reality.

In one way, the Aussie-English system is somewhat more efficient since it internalises costs to only those who benefited from the service rather than blanket taxing everyone above a certain income threshold: it allows high-income earners who did not reach such financial success from going to university to avoid paying the general penalty-tax on high-incomes that Swedish high-earners do.

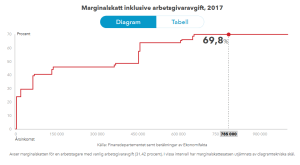

Let me show the more technical aspect: In England, earning above £18,330 places you at a position in the 54th percentile, higher than the majority of income-earners. Similarly, in Australia, $55,874 places you above 52% of Aussie income-earners. For Sweden, with the highest marginal income taxes in the world, a similar statistics is trickier to estimate since there is no official cut-off point above which you need to repay it. Instead, I have to estimate the line at which you “start paying” the relevant tax. What line is then the correct one? Sweden has something like 14 different steps in its effective marginal tax schedule, ranging from 0% for monthly incomes below 18,900 SEK (~$2,070) to 69.8% for incomes above 660,000 SEK (~$72,350) or even 75% in estimations that include sales taxes of top-marginal taxes:

If we would place the income levels at which Australian and English students start paying back the cost of their university education, they’d both find themselves in the middle range facing a 45.8% effective marginal tax – suggesting that they would have greatly exceeded the income level at which Swedish students pay back their tuition fees. Moreover, the Australian threshold would exchange into 367,092 SEK as of today, for a position in the 81st percentile – that is higher than 81% of Swedish income-earners. The U.K., having a somewhat lower threshold, converts to 217,577 SEK and would place them in the 48th percentile, earning more than 48% of Swedish income-earners – we’re clearly not talking about very poor people here.

The fact that income-earners in Sweden face a much-elevated marginal tax schedule as well as the simplified calculations above do indicate that despite its level of tuition fees at zero, it is more expensive to attend university in Sweden than it is in England or Australia. Since Australia’s pay-back threshold is so high relative to the income distribution of Sweden (81%), it’s conceivably much cheaper for Australian students to attend university than for it is for Swedish students, even though the tuition list prices may differ (the American debate is much exaggerated precisely because so few people pay the universities’ official list prices).

Letting governments via general taxation completely fund universities is a regressive measure that probably hurts the poor more than it helps the rich. The solution to this is not some quota-scholarships-encourage-certain-groups-version but rather to a) increase and reinstate tuition fees where applicable or b) cut government funding to universities, or ideally get government out of the sector entirely.

That’s a progressive policy in respect to universities. Accepting that, however, would be anathema for most people in politics, left and right.

We have seen the algorithm and it is us.

The core assumption of economics is that people tend to do the thing that makes sense from their own perspective. Whatever utility function people are maximizing, it’s reasonable to assume (absent compelling arguments to the contrary) that a) they’re trying to get what they want, and b) they’re trying their best given what they know.

Which is to say: what people do is a function of their preferences and priors.

Politicians (and other marketers) know this; the political battle for hearts and minds is older than history. Where it gets timely is the role algorithms play in the Facebookification of politics.

The engineering decisions made by Facebook, Google, et al. shape the digital bubbles we form for ourselves. We’ve got access to infinite content online and it has to be sorted somehow. What we’ve been learning is that these decisions aren’t neutral because they implicitly decide how our priors will be updated.

This is a problem, but it’s not the root problem. Even worse, there’s no solution.

Consider one option: put you and me in charge of regulating social media algorithms. What will be the result? First we’ll have to find a way to avoid being corrupted by this power. Then we’ll have to figure out just what it is we’re doing. Then we’ll have to stay on top of all the people trying to game the system.

If we could perfectly regulate these algorithms we might do some genuine good. But we still won’t have eliminated the fundamental issue: free will.

Let’s think of this through an evolutionary lens. The algorithms that survive are those that are most consistent with users’ preferences (out of acceptable alternatives). Clickbait will (by definition) always have an edge. Confirmation bias isn’t going away any time soon. Thinking is hard and people don’t like it.

People will continue to chose news options they find compelling and trustworthy. Their preferences and priors are not the same as ours and they never will be. Highly educated people have been trying to make everyone else highly educated for generations and they haven’t succeeded yet.

A better approach is to quit this “Rock the Vote” nonsense and encourage more people to opt for benign neglect. Our problem isn’t that the algorithms make people into political hooligans, it’s that we keep trying to get them involved under the faulty assumption that people are unnaturally Vulcan-like. Yes, regular people ought to be sensible and civically engaged, but ought does not imply can.

Nightcap

- Thinking about the Holodomor Flagg Taylor, Law & Liberty

- Neoliberalism is not dead Scott Sumner, EconLog

- Social generativity and complexity Daniel Little, Understanding Society

- We don’t need the UN to regulate baby formula Ryan McMaken, Mises Wire

Eye Candy: garbage versus trash (American dialects)

I’ve always said “garbage,” but down here in Texas they use the word “trash.” I have no idea where I found this, and I can’t verify the source, but it looks right to me.

Any contrary arguments about this map?

Nightcap

- Radical republicans and early modern democrats, Dutch style Dirk Alkemade, Age of Revolutions

- Did socialism keep capitalism equal? Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- John McCain in 1974 Arnold Isaacs, War on the Rocks

- U.S.-Soviet hotline a symbol of Cold War cooperation Rick Brownell, Historiat

Nightcap

- Things I hate about the US constitution Ilya Somin, Volokh Conspiracy

- At the Khmer Rogue tribunal MG Zimeta, London Review of Books

- Reductionism and anti-reductionism about painting Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- A foreign policy for the Left Samuel Moyn, Modern Age

Nightcap

- The dark side of war propaganda Bradley Anderson, American Conservative

- Is internationalism liberal or imperialist? Arnold Kling, askblog

- Internationalism is federalist, Arnold! Brandon Christensen, NOL

- ISIS and Sykes-Picot Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

A short note on Brazil’s elections

In October Brazilians will elect the president, state governors, and senators and congressmen, both at the state and the national level. It’s a lot.

There is clearly a leaning to the right. The free market is in the public discourse. A few years ago most Brazilians felt embarrassed to be called right wing. Today especially people under 35 feel not only comfortable but even proud to be called so.

The forerunner for president is Jair Bolsonaro. The press, infected by some form of cultural Marxism, hates Bolsonaro. Bolsonaro’s interviews in Brazilian media are always dull and boring. Always the same questions. The journalists decided that Bolsonaro is misogynist, racist, fascist, guitarist, and apparently, nothing will make them change their minds. Of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Bolsonaro is a very simple person, with very simple language, language that can sound very crude. But I defy anyone to prove he is any of these things. Also, Bolsonaro is one of the very few candidates who admits he doesn’t know a lot about economics. That’s great news! Dilma Rousseff lied that she had a Ph.D. in economics (when she actually didn’t have even an MA), and we all know what happened. Bolsonaro is happy to delegate economics to Paulo Guedes, a Brazilian economist enthusiastic about the Chicago School of Milton Friedman. One of Bolsonaro’s sons is studying economics in Institute Von Mises Brazil.

It is very likely that Brazil will elect a record number of senators and congressmen who will also favor free market.

Even if Bolsonaro is not elected, other candidates like Marina Silva and Geraldo Alckmin favor at least an economic model similar to the one Fernando Henrique Cardoso implemented in the 1990s. Not a free market paradise, but much better than what we have today.

Unless your brain has been rotten by cultural Marxism, the moment is of optimism.

RCH: death and taxes

I’ve been so busy I forgot about my Tuesday column over at RealClearHistory (I have a Friday column, too). Last week’s column was about the trial and execution of two Italian-born anarchists in Massachusetts:

The anarchism of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti was left-wing and violent. Very violent. The two young men were admirers of Luigi Galleani, an Italian anarchist who advocated violence as the best way to achieve a more anarchist world. Sacco and Vanzetti, the executed, were part of an American syndicate dedicated to Galleani’s ideals. This syndicate was responsible for bombings, assassination attempts, printing and distributing bomb-making books, and even mass poisonings in the United States. The Galleanists were so violent that they sat atop a list of the federal government’s most dangerous enemies. On April 15, 1920, an armed robbery at the Slater and Morrill Shoe Company in Braintree, Mass., went awry and two men, a guard and an accountant (“paymaster”) were killed by the robbers. Sacco and Vanzetti were accused, convicted, and sentenced to death.

This week’s column focused on Shays’ Rebellion:

The Shaysites, as supporters of Daniel Shays came to be known, eventually grew to thousands of men, and the movement grew confident enough that it planned to seize a federal armory. However, the governor of Massachusetts, James Bowdoin, directed a local militia leader (William Shepard) to protect the armory. The armory, though, was federal property, and the militia was operating under state direction, so the seizure of the armory in the name of protecting it from rebels had the potential to ignite a powder keg of legal ramifications throughout the war-torn eastern seaboard.

Y’all stay sane out there!

Nightcap

- In Japan, ghost stories are not to be scoffed at Christopher Harding, Aeon

- Montesquieu was the ultimate revisionist Henry Clark, Law & Liberty

- Did British merchants cause the Opium War? Jeffrey Chen, Quillette

- The eclipse of Catholic fusionism Kevin Gallagher, American Affairs