This is a draft of a book chapter that has been published as Andrei Znamenski, “From Class to Culture: Ideological Landscapes of the Left Thought Collective in the West, 1950s–1980s.” In Bolgov R. et al. (eds) Proceedings of Topical Issues in International Political Geography. Cham, Switzerland: Springer, 2021, pp. 337-354.

Ideologies never die, they metamorphose and are reborn in a new form just when they are thought buried forever.

– Pascal Bruckner, French philosopher and writer (2006)

In 2010, sociology professor Rick Fantasia, a member of the Democratic Socialists of America, struggled to explain the results of US Congress elections that were disastrous to democrats and that, at that time, brought a majority to the republicans. Fantasia was part of a Social Forum, a 15,000-strong army of left activists who gathered in Detroit, Michigan. Observing this convention, he noted that most people who arrived at this convention mostly represented various minority organizations that were either involved into identity politics or represented immigrant workers. Fantasia also noted a heavy presence of countercultural and environmentalist elements, including New Age seekers. At the same time, the activist scholar pointed out that one important element was missing: working-class people, especially white workers. With frustration, Fantasia noted that there were only a few white working-class people: “The whites were mostly educated members of the middle class, organizers, activists, representatives of philanthropic organizations and academics.” The described gathering and the expressed concern were a microcosm that reflected the shift in the entire ideology and the social base of the current Western left for the past fifty years.

What worried Fantasia was not some aberration or a temporary flaw in the left strategy and tactics. In fact, this was the result of a natural evolution of the left mainstream. Since the 1960s, it drifted away from concerns about an economic growth and class-based politics, which were associated with the old left. Instead, the left began shifting toward culture, race, and identity issues as well as environmentalism. This metamorphosis is sometimes labeled by a loose umbrella expression the “cultural turn.” On the level of ideas, this turn is usually associated with the emergence of the often-mentioned post-modernism and includes several intellectual trends and political practices that developed in the wake of traditional socialism that was heavily informed by Marxism. The most important among these trends are post-colonial studies, critical theory, feminism, multiculturalism, and political correctness. Some authors on the right refer to all this by an umbrella term “Cultural Marxism” – a pejorative expression that serves to point to genetic links between the current cultural left and the old Marxism-driven left.

This essay explores the sources of the cultural turn among the left and the development of their passion for identity matters, which resulted in the phenomenon pinpointed by Fantasia. Although there have been tons of writings about the cultural left and the origin of their woke culture, our intellectual mainstream is still dominated by the following popular notions. On the right, it is a widespread conviction that evil “Cultural Marxism,” primarily through the malicious activities of the Frankfurt School, set out to erode the Western civilization. In the meantime, the easily triggered left have been ascribing any critique of PC thought collective and its “sacred cows” of race and gender to the evil forces of fascism and racism. If we “deconstruct” the history of the left’s gradual evolution toward culture and identity, we might problematize both approaches and tone down the heated debates around that issue. Moreover, the understanding of the gradual evolution of the contemporary left from economic determinism and fixation on the proletariat to the privileging of culture, identity, and lifestyles will help us understand better how and why literally every aspect of human life became politicized in the eyes of the current left. In other words, the history of the cultural turn will shed more light on the origin of the popular left meme that personal is political.

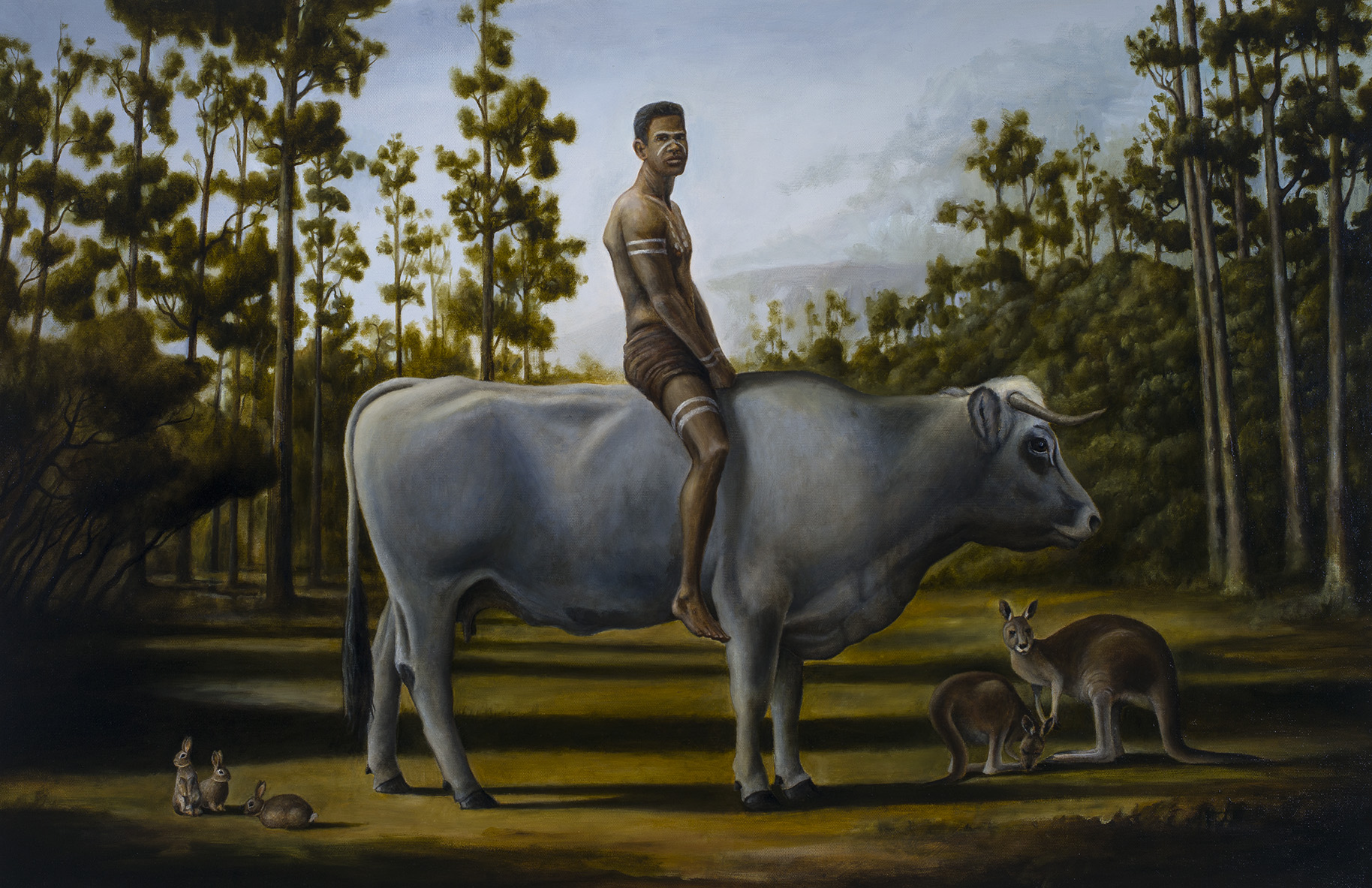

The goal of this essay is to paint a bigger picture by showing that, besides the often-mentioned Frankfurt School, there were other essential sources that fomented the cultural or identitarian turn on the left. Thus, to understand the formation of this turn, on needs to address the significance of the year 1956 and celebrity sociology W. Right Mills’ crusade against “Victorian Marxism.” We also need to bring up the writings of C.L.R. James, William Dubois, France Fanon who were the first to refurbish popular Marxism’s memes (the proletariat, class domination and oppression, the new man, false consciousness, and center-periphery) and its Eurocentric nature along racial and non-Western lines. Most important, one needs to examine the activities of British group of communist historians, Birmingham Institute of Cultural Studies, and New Left Review. Without them, it will be hard to understand the historical role of the 1960s-1970s’ New Left, which acted as an intellectual bridge between old economic- and class-based Marxism and current cultural left that is heavily steeped in identity politics.

How Do We Call It? Critical Cultural Theory, Cultural Marxism, and the Identitarian Left

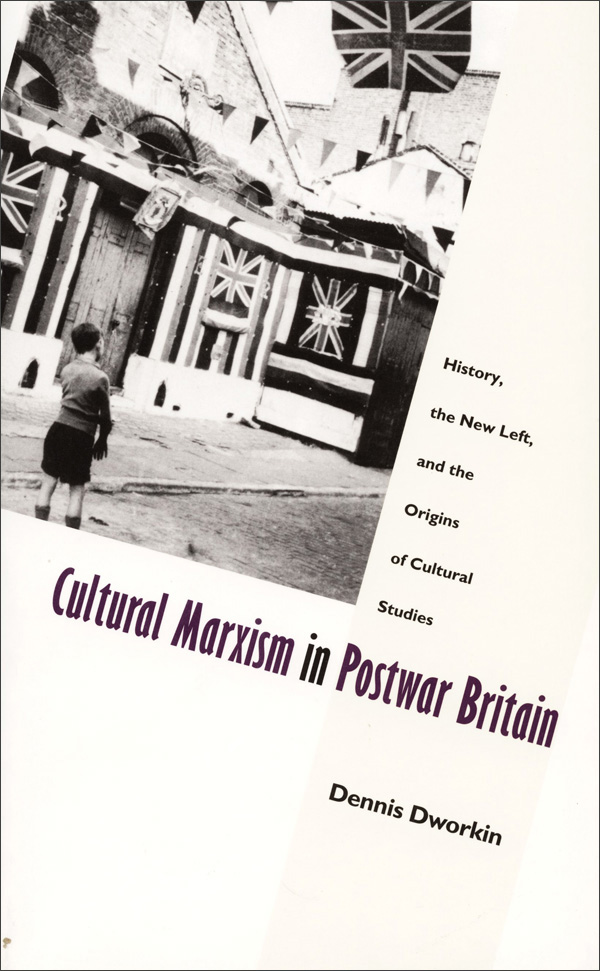

In existing debates about the cultural turn, the term “Cultural Marxism” has aroused most controversy. Current identity-oriented progressive writers and scholars do not like this expression. Their favorite term of choice is Critical Theory and the host of expressions derived from it: Critical Cultural Theory, Critical Racial Theory, Critical Legal Studies and so forth. However, earlier left authors did not see any problems with “Cultural Marxism.” In fact, between the 1970s and the 1990s, they pointed that this very expression captured well the essence of the socialist ideology that was undergoing an adjustment to the new times. For example, in his “British Cultural Marxism”(1991) Ioan Davis and Dennis Dworkin in his Cultural Marxism in Postwar Britain: History, the New Left, and the Origins of Cultural Studies (1997) did not see any problems in using that expression. Moreover, from about 2004 to as late as 2021, progressive social scholar Douglas Kellner did not find it problematic to generalize about “Cultural Marxism and Cultural Studies.”

The most aggressive among current cultural left, especially journalists who did not take time to explore the history of Marxism and neo-Marxism, have been quick to label Cultural Marxism as a hate taboo term that promotes fascist, Nazi, and anti-Semitic ideas. Using such smear metaphors, they want to intellectually link all critics of the identitarian left on the right to Hitler’s propaganda workers who had talked about “Cultural Bolshevism.” Moreover, downplaying the historical links between pre-1960s “scientific socialism” and the current cultural left, some identity-oriented left authors have claimed that they in fact moved beyond Marxism and that they are not Marxists anymore.

In their turn, many among traditional Marxist leftists, who still try to stick to the class-based approach, agree that the cultural left have nothing to do with Marxism. These “traditionalists” label their wayward cultural comrades as traitors to the cause and dismiss them as “bad Marxists”. Several scholars (historian Paul Gottfried and philosopher Helen Pluckrose), who are critical of both traditional Marxism and the current identitarian left, too have argued against using the expression Cultural Marxism. Correctly stressing that the post-Marxist left stopped prioritizing economic determinism and class and assimilated ideas from outside of Marxism, Gottfried and Pluckrose have stressed that the current cultural left hardly have any links to Marxism.

Several conservative authors (e. g. Kerry Bolton and Jeffrey D. Breshears), who generalized about Cultural Marxism, have come to view it as a grand conspiracy on the part of the left. They have portrayed it to as a sinister plan masterminded by the so-called Frankfurt School that allegedly sought to uproot Western civilization and Christianity. The most grotesque versions of the Cultural Marxism conspiracy theory link it exclusively to the activities of German-Jewish scholars (who had indeed dominated the Frankfurt School (see Benjamin Ivry, “Deconstructing the Jewishness of the Frankfurt School” (2015). That theory goes as follows. A group of mostly Jewish intellectuals, who were part of radical socialist and communist forces in the 1920s’ Germany, were upset about the failure of the 1917 Communist revolution in Europe and decided to modify the Marxist-Leninist project of world revolution by mixing Marx and Freud.

Their goal was to smash capitalism not through the cultivation of the working-class indignation but through undermining Western culture and civilization (traditional family, gender hierarchies, and sexual norms). In the 1930s, being kicked out by national socialists from Germany, the Frankfurt School cabal moved to the United States, where it became the “Trojan horses” of the radical left, setting out to undermine the culture and values of the United States – the economic and political hub of the Western civilization. One of the major proponents of this view has been writer William Lind (“The Roots of Political Correctness,” 2009), who in fact was instrumental in popularizing the expression “Cultural Marxism.” It is mostly by drawing on his writings that the left journalists came up with the argument that this expression serves as an anti-Semitic dog whistle.

While authors like Lind singled out the Frankfurt School to be demonized as the major intellectual culprit, left authors, who have been peddling so-called neoliberalism, became similarly obsessed with searching for the shadow of the Mont Perelin society in any movement that advocated free market and individual liberty. The irony of the situation is that both pejorative memes “Cultural Marxism” and “neoliberalism” do describe social trends that have been unfolding in society. They are not the products of the grand conspiracies but reflect what has been going on in the intellectual culture and on the ground among various segments of society. Incidentally, several scholars (Keith Preston, Alexander Zubatov, Allen Mendenhall, and Dominic Green) have recently explored the content of Cultural Marxism, trying to separate the conspiracy elements from actual intellectual links between Marxism of old and the current cultural left. Although I believe that this term can be useful especially when we need to stress the continuity between the old Marxian socialism and the present day cultural left, who operate with many ideological pillars inherited from the old creed (e.g. oppression/domination narrative, false consciousness and so forth), it indeed might be too narrow. So, I personally prefer to use such broad definitions as the “cultural left” and “identitarian left.”

Behind the rise of the cultural left, there stood a large thought collective that did reflect genuine concerns of various segments of the left and social movements. The writings of the Frankfurt scholars, who both analyzed Western society and did issue utopian suggestions about how to transform it, were marginal until the 1960s. Their scholarship, which helped to shift the left’s priorities from class to identity and culture, would have remained marginal had it not been for wide and vocal audiences that for various reasons picked up and consumed them. To summarize, the “Frankfurters” were not a sinister alien cabal that was preying on Judeo-Christian civilization with the sole purpose to destroy it. One can describe their effect on society by an old saying: when a student is ready, a teacher comes. In the 1960s and the 1970s, their ideas, which had earlier been marginal, suddenly began to resonate with thousands of progressives in the West and beyond. Such “Frankfurters” as Herbert Marcuse (1898-1979), Theodore Adorno (1903-1969), and Erich Fromm (1900-1980) described the development of mass consumer society, patriarchic family, the effects of propaganda on masses, criticized industrial society, and Western mass culture, frequently issuing sweeping condemnation of the entire “soulless” Western civilization.

The reason these ideas came in vogue was simply because, by the 1960s, the West and the rest of the world experienced profound socio-economic changes: the decline of traditional working class and the rise of intellectual professions, the massive involvement of women into all spheres of life and the end of the male-oriented societal ethic, which until the 1960s had been considered normal, the emergence of new technologies, an industrial pollution, and concerns about how to better handle an economic growth. Furthermore, the world saw the rise of Third World national liberation movements, the collapse of old colonial empires, and the emergence of minority movements in Western countries. Finally, the Soviet Union, which for a large portion of the left earlier had been the great new hope, lost its image as the ultimate socialist utopia. Facing those changes, the old left began to crumble. There was a need to refurbish the left ideology and identity. In the 1960s and the 1970s, during student antiwar movements, the rise of Third World national liberation movements, civil rights protests among the people of “color,” the expansion of women and gays rights movements, the ideas disseminated by the above-mentioned intellectual “power centers” of the left resonated well with thousands of protesters. One cannot simply dismiss these collectives and their ideas as something imposed from above on the “innocent populace.”

Toward “Socialist Humanism” and Away from Traditional Marxism (1956 and beyond)

1956 was a pivotal year for the socialist thought collective. This was the year when the Soviet nomenklatura elite partially exposed Stalinism, trying to polish the tainted image of socialism. The communist bureaucracy was tired of living in a constant fear, and, after the death of Stalin, it sought to secure its privileges and to somehow reform communism to make it more appealing. During the same year, taking advantage of the limited destalinization, people of Hungary openly rose in an anti-communist revolt against the Soviets. The suppression of the Budapest rebels by the Soviet tanks was a devastating blow at the moral of the millions of left idealists around the world who still believed that the Soviet Union was acting on the side of the forces of light. There was a growing frustration with the Soviet model of socialism that was tied to a total nationalization and centralized planning. Moscow was rapidly losing its status as the utopian place. It was natural that the year of 1956 signaled the emergence of the so-called New Left who sought to disentangle themselves from the Soviet experience.

In the meantime, the working-class people in the West dramatically improved their living conditions and did nor express any desire to go to barricades to battle capitalism. Social democrats were shedding the last vestiges of Marxism, and communist parties were increasingly losing their membership. For example, the French Communist Party, one of the largest pro-Soviet left movements in the West, which had 320,000 members in 1956, by 1962 shrank down to 225,000. Similarly, pro-Soviet Communist Party USA, which had between 75,000 to 80,000 members in 1945, declined to fewer than 3,000 in 1958. It was not the expected immiseration of working-class masses but an increased prosperity, bourgeois culture, and boredom that became a great challenge. The left, especially their radical wing, were poised to turn into rebels without a cause. The major character from John Osborn play (1956) expressed it best when he uttered a phrase that became classic: “There aren’t any good, brave causes left.” In 1960, Raymond Williams (1921-1988), an influential UK socialist novelist and theoretician, admitted that not only the Marxist prophecy about the immanent collapse of capitalism failed but also the entire hubris of traditional Marxism was under threat: “The Marxist claim to special insight into these matters of life and death of an economic system makes concessions of error less easy.”

There was not much to gain for the left by sticking to the economic playing field, where “rotten” capitalism was improving people’s living standards and securing an economic growth. Those who wanted to keep radical left agenda alive had to rekindle the traditional left subculture. The Trotskyites, cosmopolitan Marxist-Leninist heretics, who were the victims of vicious political assaults from their Stalinist rivals, did arouse a sympathy among dissident communists who were seeking a socialist alternative beyond the Soviet experience. After all, the Trotskyites were the first to struggle to preserve the radical elan of the Marxist creed, while simultaneously attacking both capitalism and Stalinism. Yet, with their old and worn out mantra about the primacy of an economic basis, vanguard party, and false claims about an increasing misery of the industrial working class, they were out of touch with reality. The Trotskyites simply appeared as reenactors of the bygone era and could not generate any visible support among workers, quickly degenerating into an esoteric intellectual sect.

Cornelius Castoriadis, a prominent left theoretician, captured well the whole dilemma faced by the left who were frustrated about the proletariat that failed to fulfill its prophetic mission: “The proof of the truth of the Scriptures is Revelation; and the proof that there has been Revelation is that the Scriptures say so. This is a self-confirming system. In fact, it is true that Marx’s work, in its spirit and its very intention, stands and falls along with the following assertion: The proletariat, as it manifests itself as the revolutionary class that is on the point of changing the world. If such is not the case – as it is not – Marx’s work becomes again what in reality it always was, a (difficult, obscure, and deeply ambiguous) attempt to think society and history from the perspective of their revolutionary transformation – and we have to resume everything starting from our own situation, which certainly includes both Marx himself and the history of the proletariat as a component.” Issues that became more relevant by the 1960s were the US war in Vietnam, the rise of Third World anticolonial movements, civil rights struggle, and women liberation. Traditional working-class issues became less irrelevant, whereas the issues of race, gender, and culture that earlier had occupied a marginal place on the left’s agenda, now were coming to the forefront. The mainstream radical left had to rethink their creed and agenda and customize it to the changes.

In contrast, by the 1960s, Moscow, which had billed itself as Red Jerusalem and the vital center of left radicals appeared as conservative, oppressive and ideologically suffocating. In the 1930s and the 1940s, the sympathetic left somehow could excuse Stalin’s socialism along with its police state, terror, and labor concentration camps as a temporary mobilization scheme that was needed to successfully fight fascism and railroad backward Russia into the radiant world of modernity. Yet, after 1956, it became harder to justify the continuation of that politically correct line. For example, in response to Soviet defector Victor Kravchenko’s revelations of Stalin’s crimes in 1946, European communists and their fellow travelers still felt no shame in dismissing the existence of GULAG concentration camps as fake news, and large segments of public swallowed it. Yet, ten years later, when Stalin’s heir Nikita Khrushchev himself indirectly revealed the brutal reality of Soviet communism, the cannibalistic nature of the Bolshevik-made regime was impossible to deny. Without wishing this, the Soviets, who themselves denounced Stalin, the “red pope” of communism, made a huge crack in the entire building of the socialist faith. 1956 produced thousands of apostates. Several of them released a volume of their testimonies with a revealing title God That Failed.

Since 1956, to dissociate themselves from the Soviet brand of socialism, the Western left sought to humanize Marxism. Hence, a natural shift away from economic determinism and economic efficiency toward the issues of culture and identity. Later, this trend manifested itself in the emergence of such contemporary memes as “socialism with a human face,” “democratic socialism,” “socialist humanism,” and “Marxism-Humanism.” A Jamaican-born UK Marxist sociologist Stuart Hall, one of the fountainheads of the cultural turn on the left, remembered that he and his comrades wanted to find a new political space through the rejection of both Western social democracy and Stalinism. The expression “Stalinism” became an important euphemism for those among the radical left, who wished to exorcise Stalin from communism and socialism, but who simultaneously wanted to preserve the reputation of these two sacred words untarnished.

“Sense of Classlessness” and British Cultural Studies, 1950s-1970s

One of the major trailblazers of the drift toward humanized Marxism and culture and away from economic determinism was a dissident group of British Marxist intellectuals who were later labelled as the New Left. Several of them came from so-called Communist Party Historians Group that was set up within the British Communist Party in 1946. Others were communist fellow travelers or independent Marxists. At the end of the 1950s, when the Moscow commanding heights began to question Stalin’s infallibility, these historians, sociologists, and literary scholars either quit on the party or drifted away from traditional Marxism-Leninism, challenging its Stalinist theory and practice. These dissident intellectuals included such prominent figures as E. P. Thompson (1924-1993), Herbert Hoggart (1918-2014), Christopher Hill (1912-1996), Raymond Williams (1921-1988), Christopher Hill (1912-2003) Stuart Hall (1932-2014), Raphael Samuel, (1934-1996), John Saville (1916-2009), Eric Hobsbawm (1917-2012), George Rudé (1910-1993) Rodney Hilton (1916-2002). Several of them (Hall, Hobsbawm, Hoggart, Thompson, and Williams) had a profound impact on Western social scholarship, especially in English-speaking countries. For example, Hall and Williams literally laid the foundations of current cultural studies. In their turn, Thompson and Hobsbawm had a huge impact on history scholarship, helping to shift its mainstream direction toward writing about the past “from below.”

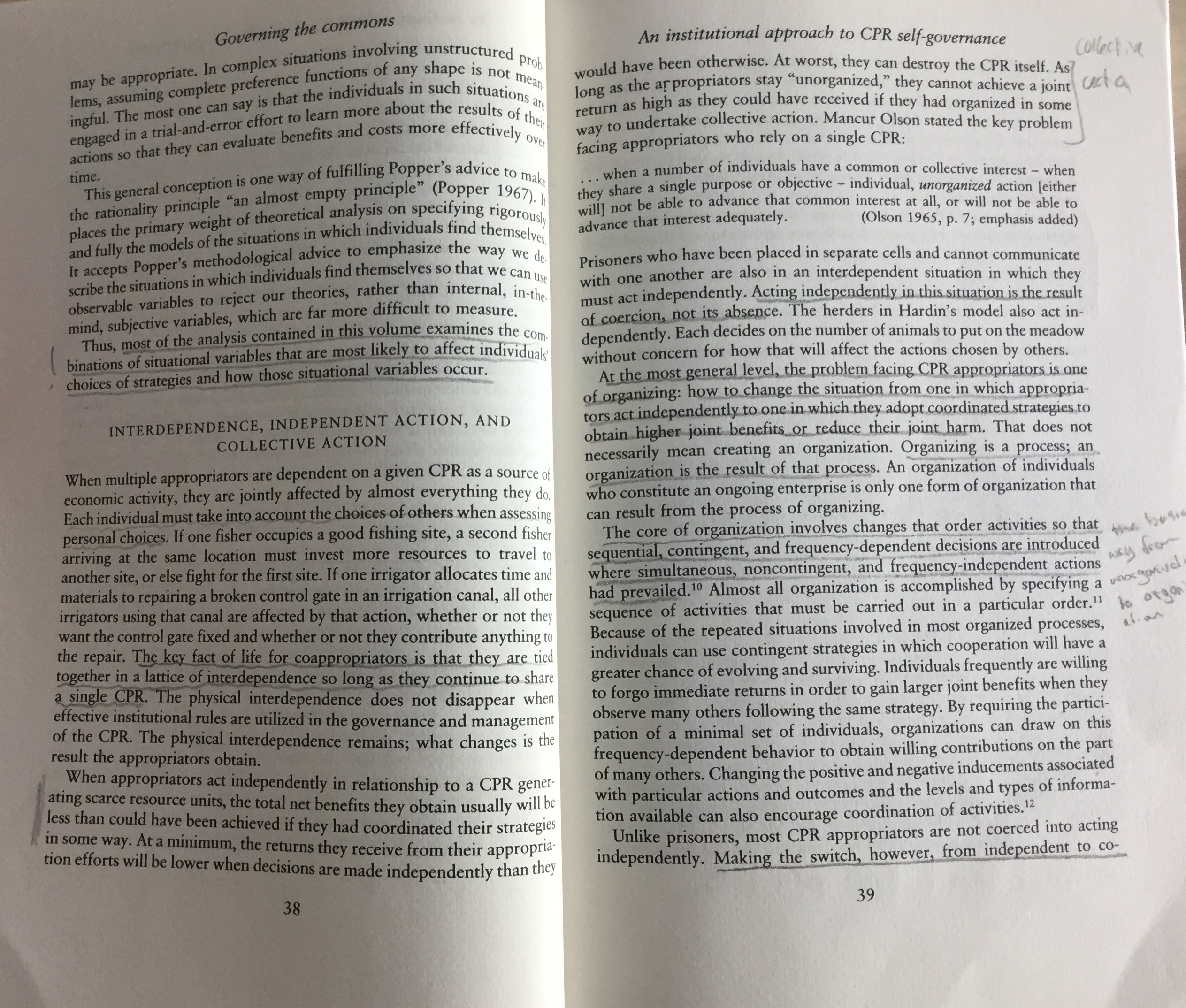

These New Left dissidents began to question the old Marxist notion that the end of capitalism was linked to the increasing immiseration and economic degradation of the proletariat. Instead, they started arguing that the need for socialism was arising from the bourgeois affluence and consumerism. Furthermore, these ex-communists cracked the traditional Marxist conviction that economic class interests conditioned politics, social life, people mindsets, and culture. Gradually shedding off economic determinism, these left scholars who had invested their whole careers into “scientific socialism,” found a new outlet to continue their intellectual pursuits – retrieval of the popular culture of working-class people.

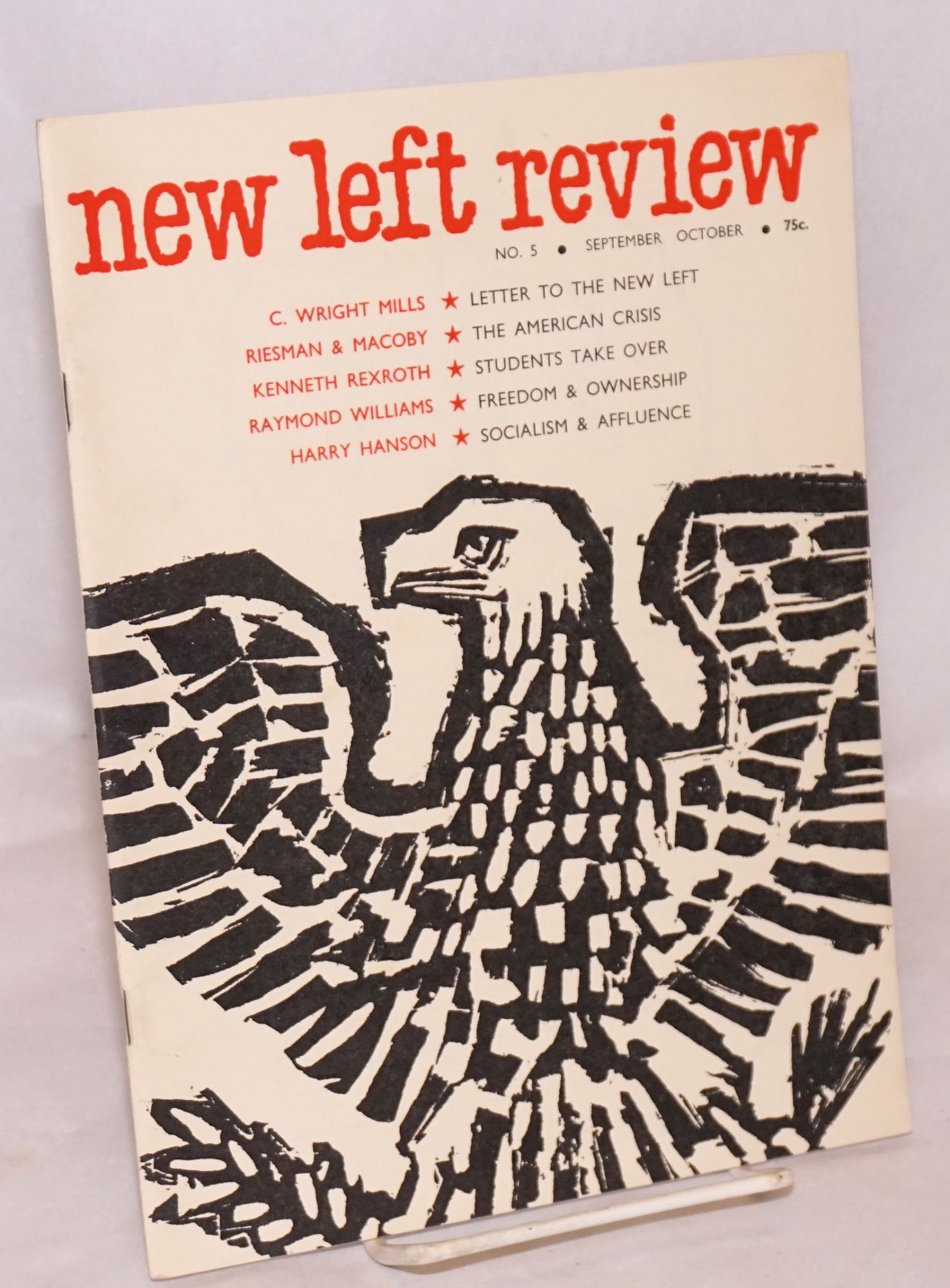

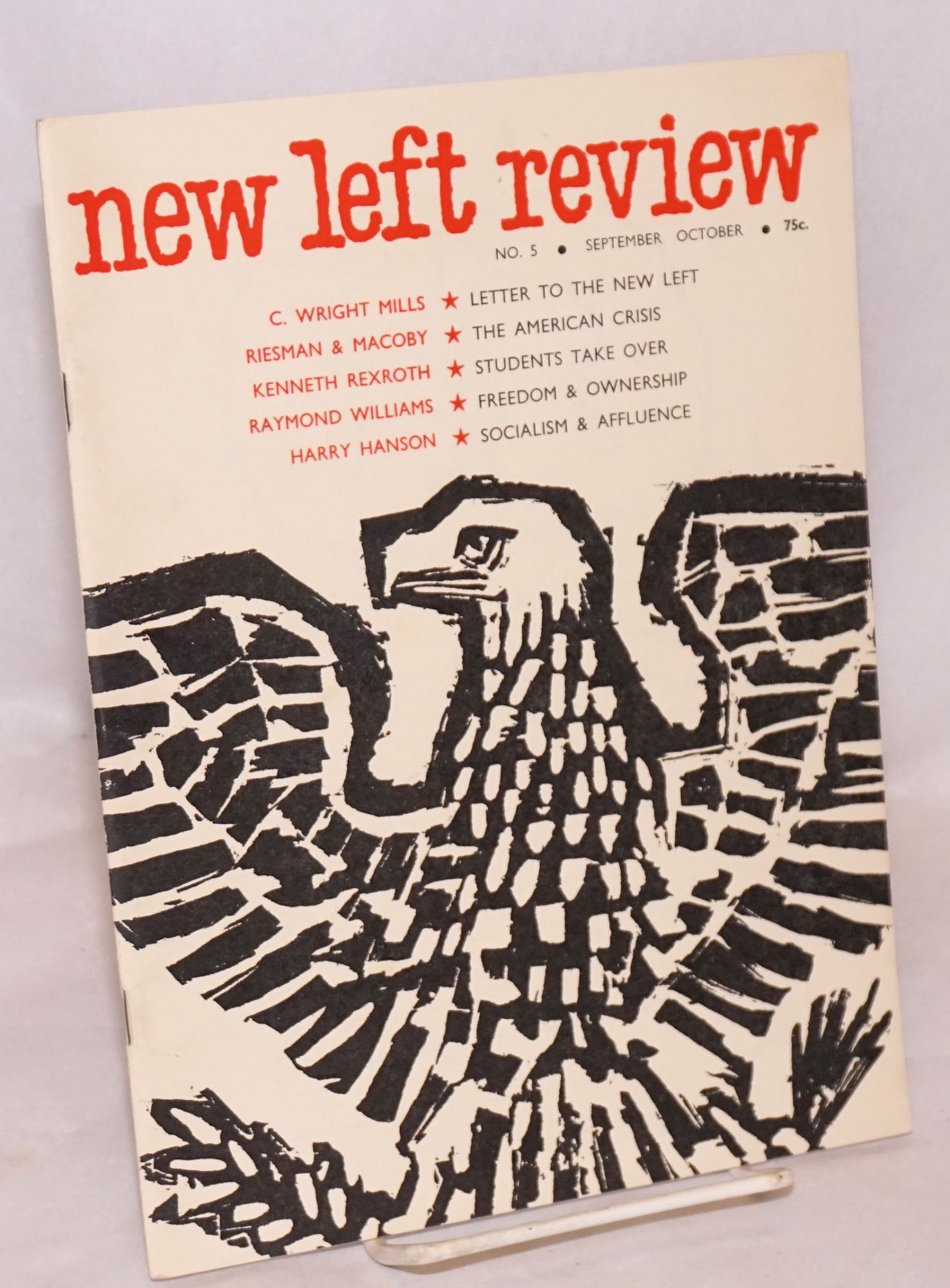

Their intellectual quest eventually gave rise to New Left Review. Launched in 1960, it became the major periodical of the Western New Left. In fact, the very expression “the New Left” originated from a collective that congregated around this journal and that was hanging in and around the Partisan Coffee House in Soho, a bohemian area of London, and the Birmingham Institute of Cultural Studies. Searching for a new identity, the New Left changed the very concept of political, moving away from the traditional left “sacred sites” such a factory and a trade union to the realm of labor culture, folklore, lifestyles, and individual behavior. Hall, who was part of this ideological collective, noted that he and his comrades were looking for a better place to ground their radical socialism. Incidentally, one of his speculative essays carried a characteristic title “A Sense of Classlessness.” Hall specified that the major way for him and his comrades to anchor themselves was politicizing various issues surrounding college life, high schools, movie theaters, art and other walks of life and institutions. Jumping ahead, I want to stress that for the current cultural left politicizing the issues of lifestyle is one of the major ways of sustaining their identity. Hall defined the New Left ideological search as “the proliferation of potential sites of social conflict and constituencies for change.” The famous slogan of radical feminism “the personal is political” captured well the essence of that quest. Overall, as Hall stressed, all kinds of issues, including personal troubles and complaints could be amplified and opened to politicization.

Trying to downplay the old mantra about how economy conditioned the minds of proletarians, these anti-Stalinist dissidents shifted attention to learning about the wisdom of working class by exploring its culture and folklore. One of the first timid steps was made by Thompson, a professional historian and one of those communist dissidents. Although Thompson continued to romanticize the labor as the ultimate savior of humankind from capitalism, the scholar nevertheless admitted that the cause of the intellectual bankruptcy of Marxism-Leninism was its economic determinism. Drawing on Marx’s The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), one of a few foundational texts in classical Marxism that did recognize a relative autonomy of political culture, Thompson invited to pay more attention to the spontaneous agency of people over the working of invisible natural laws. Simultaneously, he criticized contemporary Marxism for downplaying moral and ethical issues. Thompson is mostly known for multiple editions of his The Making of the English Working Class (1963) that became a staple reading in history and humanities courses throughout English-speaking world. In this book, he drew attention to the radical culture of English labor.

Williams, political scientist and literary scholar who belonged to the same collective, moved far further toward embracing a cultural approach to the proletarian “chosen people.” Formally remaining a member of the British Communist Party, in the 1950s, Williams gradually drifted away from it toward the Labour (social democratic) platform. Unlike Thompson, who was still trapped within the old Marxist bubble, Williams went full ahead in fomenting the cultural shift in Western Marxism and one of the most influential thinkers for the entire Anglo-American left social scholarship community. Moreover, to dramatize his opposition to the economic materialism and determinism of traditional Marxism, Williams labelled his method as “cultural materialism”; because of Williams’ aggressive media presence, his ideas about the working-class culture and group identity trickled down into Western humanities, where later they were used as a methodological blueprint for feminist, racial, gay, and queer theories.

To legitimize the cultural shift, the dissidents had to appeal to the authority of foundational Marxist texts and use relevant quotes from its founders. Just as their Soviet counterparts who, when partially cleansing the house of Stalinism, turned to Marx and Lenin, the Western New Left had their intellectual “Reformation” by invoking the early writings of Marx. Besides such writings as The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, they particularly became interested in so-called Economic and Philosophic Manuscripts (1844), vague and abstract notes made by young Marx about humanism and alienation. Excavated and published by Bolshevik scholars in Moscow in the 1920s, those notes appeared to contemporary radical socialists as irrelevant: they did not yet contain the famous pillars of Marxist “science” such as surplus value, the primacy of economic basis, socio-economic formations, and the salvational role of working class. In the wake of the 1917 revolution, being busy with class battles and ready to harness the “laws of history” in order to usher in the radiant communist future, Bolsheviks and their radical left allies in other countries did not pay much attention to those manuscripts, considering them raw speculations of the great mind in its infancy. Yet, during the unfolding New Left revisionism, which aimed to mute economic determinism and the Stalinist totalitarianism, amplifying instead the significance of the human being, culture, and identity, those vague notes suddenly became relevant and “mature.” What especially resonated with the British dissident Marxists and the New Left in general was Marx’s generalizations about alienation of human beings in modern Western society.

The ultimate task was to revise the traditional Marxist canon, which preached that economic basis conditioned political and cultural “superstructure,” and to place instead an emphasis on the “superstructure.” In his Culture and Society (1960), Williams furnished relevant quotations from the writings of Marx and Engels to make a case that the cultural superstructure should not be reduced to the economic basis. Instead of old speculations about the economic conditions of the working class in England, the historian was on the quest for the traditional working-class culture, which he romanticized as organic, wholesome, and authentic. Moreover, Williams sought to separate it from “artificial” bourgeois mass culture. A sympathetic contemporary aptly remarked that the intellectual quest of Williams and his New Left colleagues who sought to pinpoint an “authentic” proletarian culture was an attempt to merge “imaginative literature and socialist humanism.”

Marxist sociologist Hoggart, who founded the Birmingham Center for Contemporary Cultural Studies in 1964, too portrayed the idealized working-class culture as organic and natural, contrasting it to the “non-authentic” bourgeois culture. According to Hoggart, mass bourgeois culture was undermining and phasing traditional and wholesome working-class ways. It was natural that Williams and Hoggart, who celebrated the bygone traditional labor culture, became drawn to Romantic poets and writers who celebrated Merry Ole England. In fact, their intellectual speculations surprisingly resembled dismissive rants of conservative critics regarding modern British culture. Irving How, a walk away American Trotskyite and socialist sceptic who was observing these cultural speculations of his English comrades, could not resist making a comment: “I suspect that in their stress upon the working-class neighborhood and its indigenous culture men like Williams and Hoggart are turning to something that is fast slipping away.”

Another prominent member the same group of dissident Marxists historian Hobsbawm, whose books became must read in many history and anthropology courses, gives us an example of a true-believer who was literally tormented by the idea of how and where to find a “class-savior” at that age of “classlessness.” Unlike his wayward comrades such as Thompson, Hobsbawm, chose to remain in the British Communist party. Moreover, at the turn of the 1950s, still infested with the idealism about the proletariat as the ultimate victim-savior, the historian put his two cents in the famous debate about the effect of the Industrial Revolution on the living conditions of the working class in England. In the spirit of classical Marxism, Hobsbawm was trying to argue that by 1800 the life of the factory laborer had become miserable if compared with the preindustrial Britain. By the way, it was the very same debate that also produced collective volume Capitalism and Historians (1954), in which F. A. Hayek and his colleagues challenged arguments of Hobsbawm, Thompson and the like, arguing that the living condition of workers had significantly improved. In the end of the 1950s, being unable to operate on the familiar economic playground of classical Marxism, Hobsbawm slowly began to drift toward new “pastures” in the Third World. At the turn of the 1960s, he took several trips to Latin America, exploring revolutionary movements in that part of the world, falling for Cuba and engaging Peruvian peasants into talks about the level of their oppression. At some point, Hobsbawm became so excited about the revolutionary potential of Latin America that he defined it as the engine of the future socialist revolution.

In 1959, he published Primitive Rebels. This book that became a runaway bestseller in the English-speaking world was also translated in all major European and Asian languages. In fact, the enthusiastic reception of the text demonstrated that he did tap in the popular longing among the left to find new “chosen ones” to letch on. Although the current identitarian left will find that title too patronizing and Eurocentric, Primitive Rebels did clear the ground for the cultural turn in the general shift away from the proletariat. The book represented a history account that romanticized people whom Hobsbawm defined as social and noble bandits, from English Robin Hood types and Sicilian mafia to peasant communism in Italy and Ukraine and Spanish anarchists of the 1910s-1930s. The indirect message of the book was that all those segments fomented a spontaneous social justice by undermining oppressive systems. In fact, the most recent American paperback edition of the book has been advertised as a timeless text that would be relevant to Black Lives Matter activists who sought to protect black ghettos from alleged police brutality.

Those independent New Left, who were not constrained by ties to the communist movement like Hobsbawm, went further and began to completely debunk the role of workers as the “chosen people” destined to save the world from capitalism. In 1960, American sociologist C. Wright Mills (1916-1962), an emerging intellectual guru of the New Left, openly challenged the “labor metaphysic” of the old comrades. He scorned the romancing of the proletariat as “Victorian Marxism” and a survival of the past. Trying to fill the old Marxist clichés with a new content, the sociologist insisted that in the new “post-industrial” conditions, the true catalyst of revolutionary changes would be the intellectuals in the West, Soviet bloc countries, and the Third World. People like Thompson, who continued to believe in the proletarian class struggle, were confused and upset about such flamboyant attack on the sacred pillar of Marxism. On the one hand, they wanted to exorcise Stalinism and economic determinism from “scientific socialism.” Yet, on the other hand, they were too attached to the old ideological meme of proletarians as the “chosen people” to simply cast aside this foundational stone of the Marxist theology. Still, blended with “racialized Marxism” of Dubois, James, and Fanon, Mills’ heretical ideas, Thompson, Hoggart, and Williams and Hobsbawm scholarship opened doors to the emergence of the identitarian left.

C.L.R. James, William Dubois, Frantz Fanon, and the “Curse” of the Western Civilization

Moving further away from the sacred pillars and sites of traditional Marxism (a factory, economic growth, the working class, and the Soviet Union), such activist intellectuals as Hall became known as the New Left. From the economic critique of capitalism, which did not make sense at the time when this very capitalism improved workers’ living standards, the New Left gradually began to take on the Western civilization in general, bourgeois life-styles and culture, embracing the Third World and non-Western cultures. The slowdown of class battles and sluggish radical socialist activism in the West contrasted with the great awakening in the Third World, where emerging national liberation movements challenged European colonialism. Cast against the “dormant” and “corrupted” Western working-class, the Third World appeared to the New Left as the potential hub revolutionary activism.

It was increasingly clear that the Europe-centered old left hardly had anything to offer in the new socio-political circumstances. Hall remembered, “I was troubled by the failure of Orthodox Marxism to deal adequately with either ‘Third World’ issues of race and ethnicity, and questions of racism, or with literature and culture.” Another Caribbean expat and his French counterpart Aime Cesaire, a budding New Left intellectual from Martinique, declared his resignation from the French Communist Party, rebuking Eurocentric paternalism of the communists.

To be exact, there were already several major writers on the left who had inaugurated this drift away from the West toward the Third World, culture, and identity matters. In fact, Vladimir Lenin, one of the giants of the radical left, had opened a space for the cultural rereading of Marxism by endorsing the anti-colonial resistance as the European proletariat’s ally and pointing to the commonality of interests between the European “wretched of the earth” and the colonized people. Moreover, feeling the need to placate various local nationalisms in the emerging Soviet Union and to win allies in the non-Western colonial periphery, Lenin drew a distinction between “bad” regressive nationalism of the bourgeois West and “good” progressive nationalism of the colonial periphery. Without wishing it, Lenin made a crack in classical Marxism that had taught that colonialism had been progressive because it had brought industry to the undeveloped parts of the world. Earlier, it was assumed that boosting the expansion of capitalism sped up the formation of the proletariat – capitalism’s gravedigger – and the movement toward the radiant communist future.

Among the influential early voices that triggered the identitarian revision of Marxism was W. E. B. Dubois (1868-1963), an African American social scholar, nationalist, Soviet fellow-traveler, and a convert to communism at the end of his life. The other one was C.L. R. James (1901-1989), an independent Marxist novelist and theoretician from a British Caribbean colony of Trinidad. The third was Frantz Fanon (1925-1961), yet another Caribbean-born black intellectual from the French-owned island of Martinique, who was instrumental in merging Marxism, Pan-Africanism, and Third World nationalism. Since the 1960s, the New Left and their successors among the cultural left have been holding all three in a high esteem. In fact, in academia there grew entire publication industry around those personalities.

Early in his career, along with socialism, Dubois absorbed then popular race and “folk soul” ideas when he was studying in Germany between 1892-1894, applying them to his budding Black nationalism. In his 1897 “The Conservation of Races,” Dubois called for the cultural unity of the “Black race” to replicate the efforts of the Teutons, Slavs, Anglo-Saxons, Latins, Semites, Hindu, and Mongolians who were busy, as he explained, consolidating their own civilizations. Dubois viewed the American blacks as the enlightened vanguard of the black race that was to perform that job of consolidation. He envisioned such racial solidarity as a counterweight to the contemporary domination of the “whiteness of the Teutonic” and their soulless civilization that was fixated on individualism and economic enterprise. Very much like his racially-conscious Germanic contemporaries, who lamented the degradation of the Aryan soul by corrupt forces of modern industry and commerce, Dubois generalized about the bourgeois civilization of the West corrupting Africa – the primal and vital center of the black race.

In his Souls of Black Folk (1903) and Negro (1915), he spoke in favor of segregating “black culture” from “white civilization” and speculated about an abstract black soul, race, and culture devoid of any local and linguistic differences. In fact, later in 1934, Dubois severed his connections with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People that was working to eliminate racial segregation in the United States because the organization’s activities contradicted the racial utopia he contemplated. Interestingly, in his novel Dark Princess (1928), Dubois portrayed the Atlas Shrugged-type society of non-white expatriates who formed the Great Council of the Darker Peoples. Represented by “dark” superheroes, that society was planning to take over and engineer a happy future on the planet after white institutions collapsed.

Dubois relied on European romantic memes of the noble savage (collectivist, generous, wholesome, happy, simple), which he applied to all blacks as a race. Also, drawing on his parochial experience as a black American, the writer singled out race as the central factor in the world history, and slavery as the experience that defined not only the past history but also conditioned future behavior of his “tribe.” Dubois assumed that the sheer presence of “black blood” in an American automatically made such a person a carrier of the “soul experience” of being a slave; incidentally, none of Dubois ancestors had been in bondage. Dubois welcomed the 1917 Bolshevik Revolution that he considered as a scorching wind that was to cleanse the modern world, washing away bourgeois civilization. Since the Soviet Union crusaded against the West, he automatically viewed that country as an ally: the enemy of my enemy is my friend. By 1935, Dubois came to conclusion that the Soviets would destroy the “rotten” Western civilization and help to construct a new non-Western cultural order. The writer praised Stalin as a great liberator, and the 1956 revelations of the Soviet crimes did not shatter this conviction. Reflecting contemporary political preferences of Third World anti-colonial leaders and spokespeople, he called the Soviet Union and China the shining models of the future. His conversion to communism and subsequent move to Ghana in 1961, where he became a senior advisor to Kwame Nkrumah, the head of the country who claimed building socialism, was symbolic. Here on the African soil, his black nationalism, which was saturated with romantic memes of European primitivism, met Marxian socialism. There is no need to stress that Dubois writings has been a must read in many humanities and social science courses across Western academia since at least the 1970s.

The evolution of C.L.R James, who became another must reference for Western social scholarship, moved in a reverse direction, although the result was essentially the same. From early on, in the 1930s and the 1940s, he prophesized his loyalty to Marxism. Yet, gradually, James began to play down class exploitation, amplifying the significance of racial and colonial oppression. It was natural because these issues were personally more relevant to him than far-away class battles in distant and alien Europe. James at first embraced anti-Stalinist Trotskyite version of communism and its prophecy of the world revolution. Yet, later, driven by anti-colonial concerns and by a desire to identify a new reliable revolutionary force to act as a surrogate proletariat, he shifted his attention to the Third World.

Essentially, both Dubois and James were refurbishing the classic Eurocentric prophecy of Marxism along the Third World lines. Marx had welcomed colonialism as a progressive system that was sucking underdeveloped areas into the global commodity economy, pushing the world closer to capitalism and creating an economic basis for a leap into the radiant communist future. For him, slavery was an archaic mode of production that, at the dawn of human history, had boosted economic development and then perished, giving rise to more progressive stages of human evolution such as feudalism and then capitalism. According to the founder, slavery survived in some backward areas of the globe (US South, Latin America, Africa) that did not catch up yet with the industrial West. In contrast, James and Dubois argued that slavery was not a vestige of the bygone socio-economic formation, but, more than the exploitation of European proletariat, was an essential part of modern capitalism.

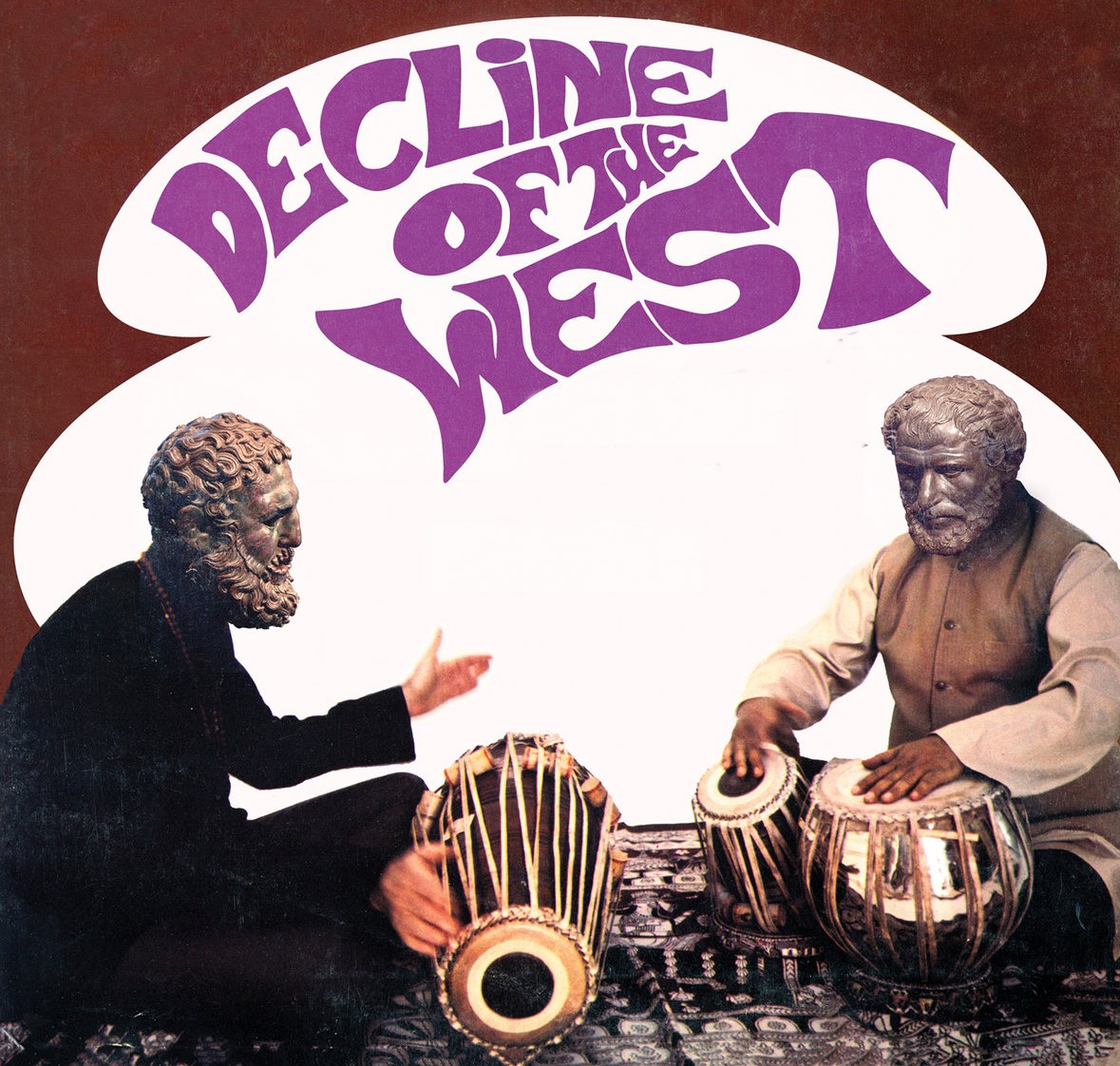

They insisted that slavery and exploitation of colonies were the vital resource that made possible the rise of capitalism. Moreover, they became convinced that the entire Western prosperity was accomplished at the expense of non-Western people. Again, in contrast to Marx who viewed capitalism as a progressive stage on the way to communism, James and Dubois began to argue that capitalism was not a progressive but a regressive system – a European cultural institution imposed on the rest of the world for the purposes of exploitation. It is notable that, when singling out two pivotal books that had affected his worldview, besides Leon Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution (1932) James mentioned The Decline of the West (1918) by Oswald Spengler. The latter text, which was saturated with a deep pessimism, prophesized the decline of the Western civilization. Incidentally, Spengler too greatly affected Dubois who began taking for granted that the West was in perpetual decline. Both found in the German philosopher’s text what they were looking for: a radical criticism of the entire Western civilization.

The crucial role in shifting Marxism toward race and identity issues belonged to Fanon, a popular anticolonial writer whose landmark text The Wretched of the Earth (1961) became a book of choice for the whole generation of the Third World national liberation activists in the 1960s-1970s. Fanon’s bashing of the West also won him numerous disciples in the countercultural circles and among the New Left in Europe and the United States. As Kalter reminds to us, since the 1980s, assimilated by the academic left (post-colonial studies and critical race theory) into educational system and media, his writings later became an important intellectual fountainhead for identity studies and identity politics.

A psychotherapist by profession, Fanon was a French-speaking intellectual who took part in the Second World War and then in the Algerian War of independence (1954-1962). In his writings, he focused not on economic liberation but on the cultural and psychological decolonization of the Third World. Drawing on Marxist class clichés, Fanon revised them along racial lines: “You are rich because you are white, you are white because you are rich.” Fanon insisted that the colonial periphery became the mentally imperiled by Western values, which natives needed to shed off because these were “white values”: “Come, comrades, the European game is finally over, we must look for something else. Let is not imitate Europe. Let us endeavor to invent a man in full, something which Europe has been incapable of achieving.” In his view, Europe was deadly sick and the keys to the liberation of humanity were in the hands of the Third World that was destined to shape the New Man; incidentally, the latter meme also originated from Marxism. Fanon’s friend Jean-Paul Sartre, a famous French philosopher and Soviet apologist, felt happy that “the most ardent poets of negritude are at the same time militant Marxists.” Yet, repeating the mantra of the old left, Sartre said that the mingling race with that class was “not a conclusion” but a transitional stop on the way to a greater color-blind commonwealth. When Fanon read these Sartre’s words, he felt utterly offended as if he was robbed of his identity. Contrary to what his philosopher friend believed, for Fanon, “racialized Marxism” was the conclusion.

Traumatized by the brutalities of the French he witnessed during the Algerian liberation war, Fanon insisted that nothing connected the colonizers and the colonized except racist violence. Ignoring the multitude of social, economic, and cultural relations in the contemporary colonial and post-colonial periphery, he argued that “the colonial world is a Manichean world.” In his irreconcilable “black and white” world, oppressed victims held the ultimate truth because of their sheer status of being colonized people. To Fanon, morality and truth were relative. They depended on how well these two things served a liberation cause. This included lying and committing violence, provided these vices served a good cause. Stressing that truth was a matter of political expediency, he wrote, “Truth is that which hurries on the break-up of the colonialist regime; it is that which promotes the emergence of the nation; it is all that protects natives, and ruins foreigners. In this colonialist context there is not truthful behavior: and the good is quite simply that which is evil to ‘them’.”

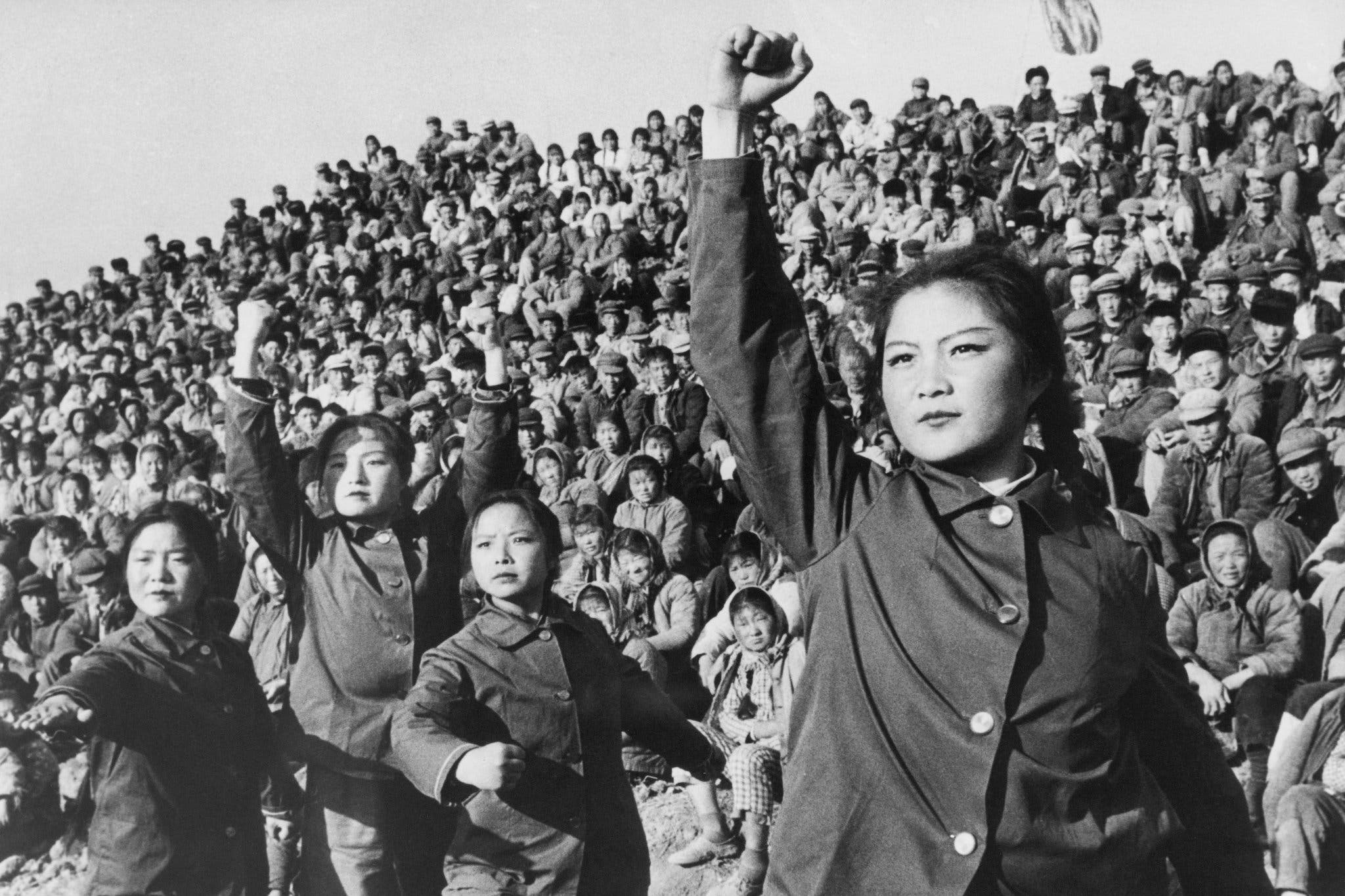

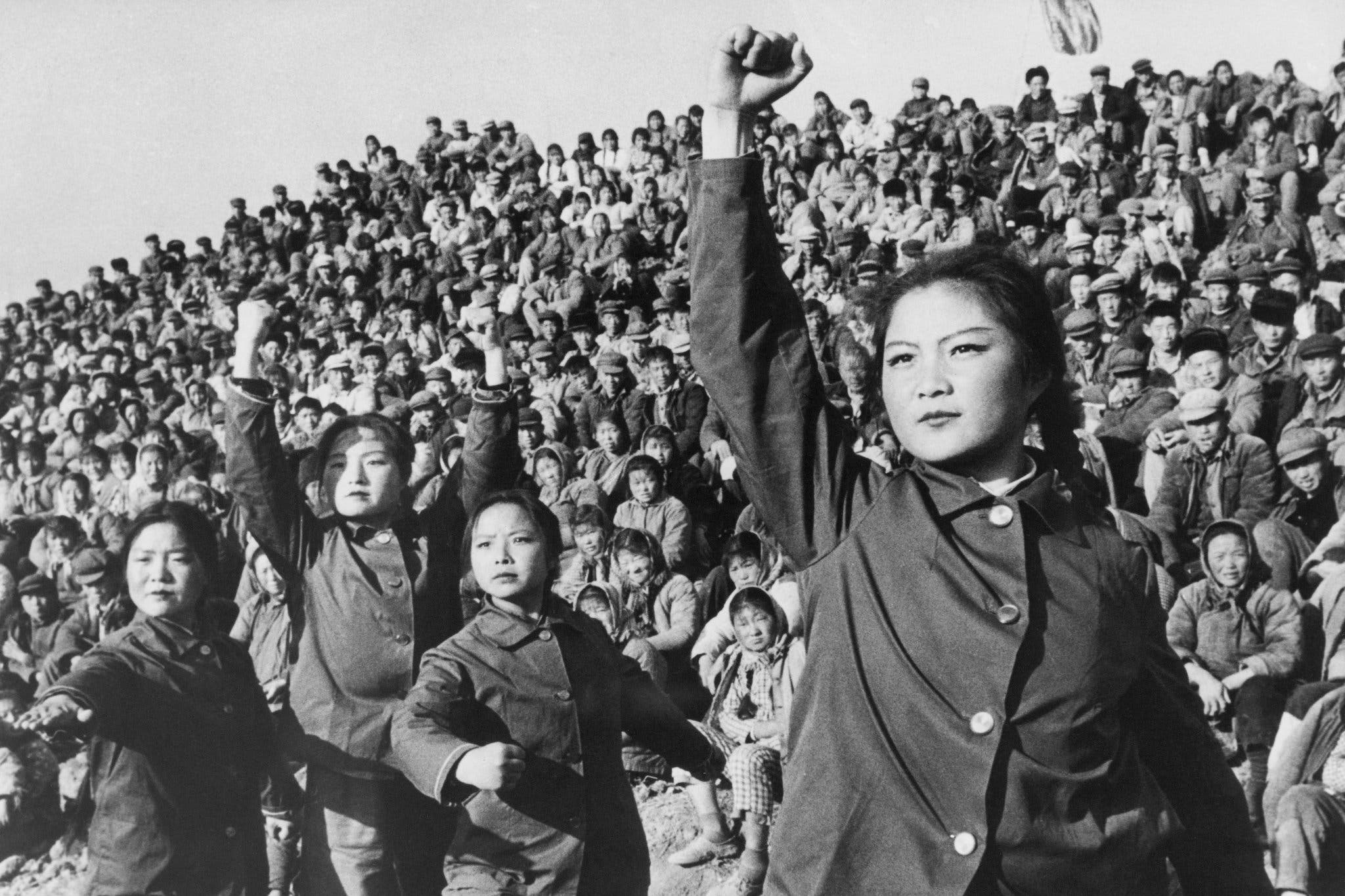

To overcome their oppressive state, the colonized had to take the place of their masters by resorting to a redemptive violence. The natives, who wasted their energy in mutual tribal conflicts and indulged into ecstatic tribal dances, were to channel their energy into the anti-colonial violence against whites. In fact, violence occupied an important place in the entire Fanon’s liberation philosophy. In The Wretched of the Earth (1961), he romanticized violence and attributed to it pedagogical value: “Violence alone, violence committed by the people, violence organized and educated by its leaders, makes it possible for the masses to understand social truths and gives the key to them.”” Fanon viewed violence not only as a tool of liberation and education but also as a powerful vehicle of a nation-building and racial consolidation. In the process of their struggle, oppressed natives were expected to nourish the sense of a unified collective: “Individualism is the first to disappear,” and “the community triumphs.”

Using Marxist class categories and simultaneously filling them with a new content, Fanon argued that in undeveloped colonial countries the only revolutionary class was peasants. These rural masses carried armed struggle from the countryside into cities. This meant that the class that was to liberate the colonial periphery and the rest of humankind from capitalism was not industrial workers (proletarians) but the Third World peasantry. With such a view, Fanon naturally came to idealize Third World peasant collectives as the cradle of the ideal human commonwealth. Invoking the romantic meme of European primitivism, he contrasted “evil” Western individualism with the “noble” African culture of collectivism represented by village councils, people’s committees. According to Fanon, the anti-colonial struggle was to rekindle and strengthen those collectives. Moreover, a solidarity nourished during an anti-colonial war was to heal a corrupt indigenous bourgeoise – the creature of the West. Through its involvement into the common anti-colonial movement, this bourgeoise would reunite itself with its indigenous soil, merging with common into a united Gemeinschaft-type people’s community.

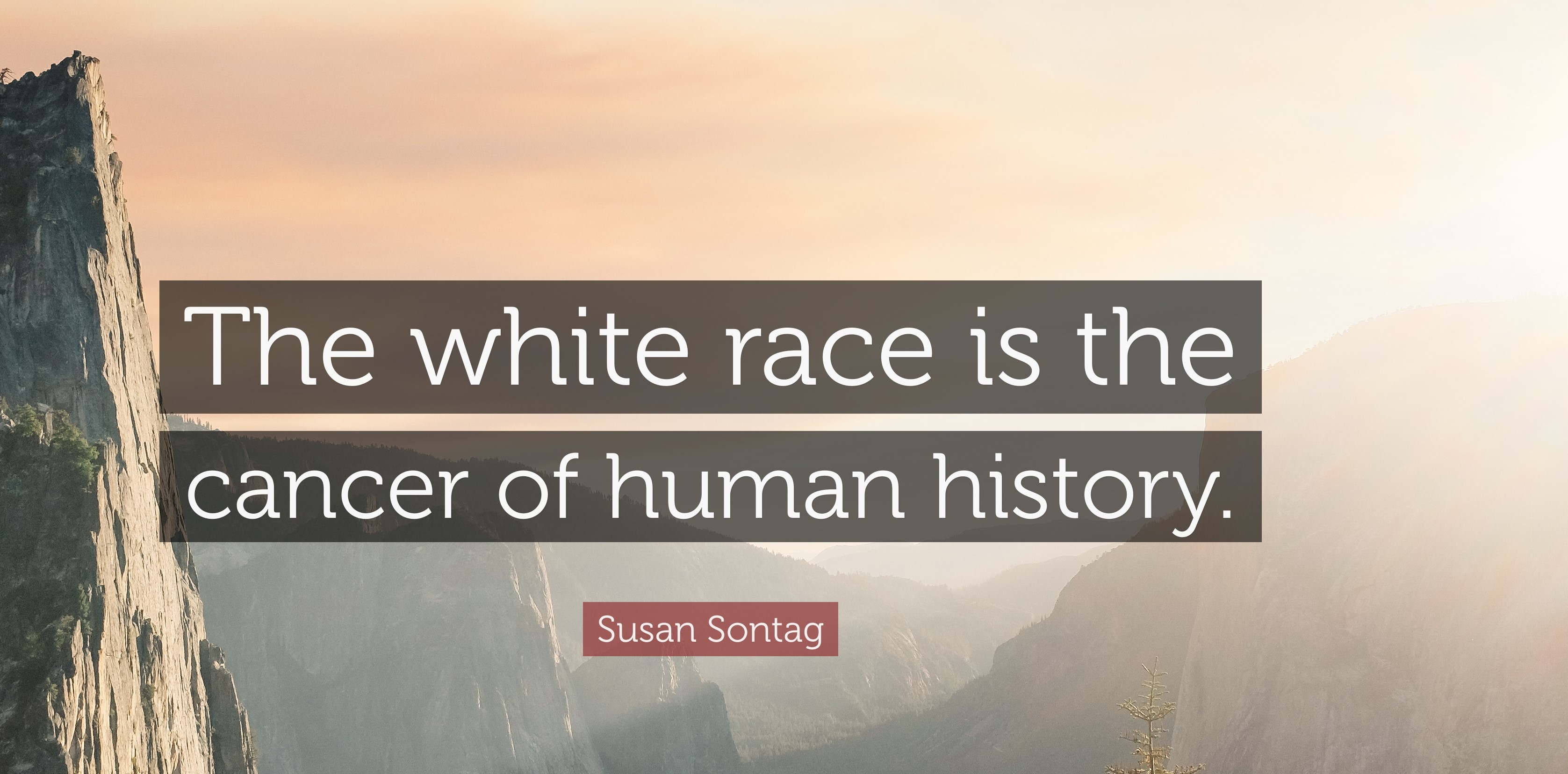

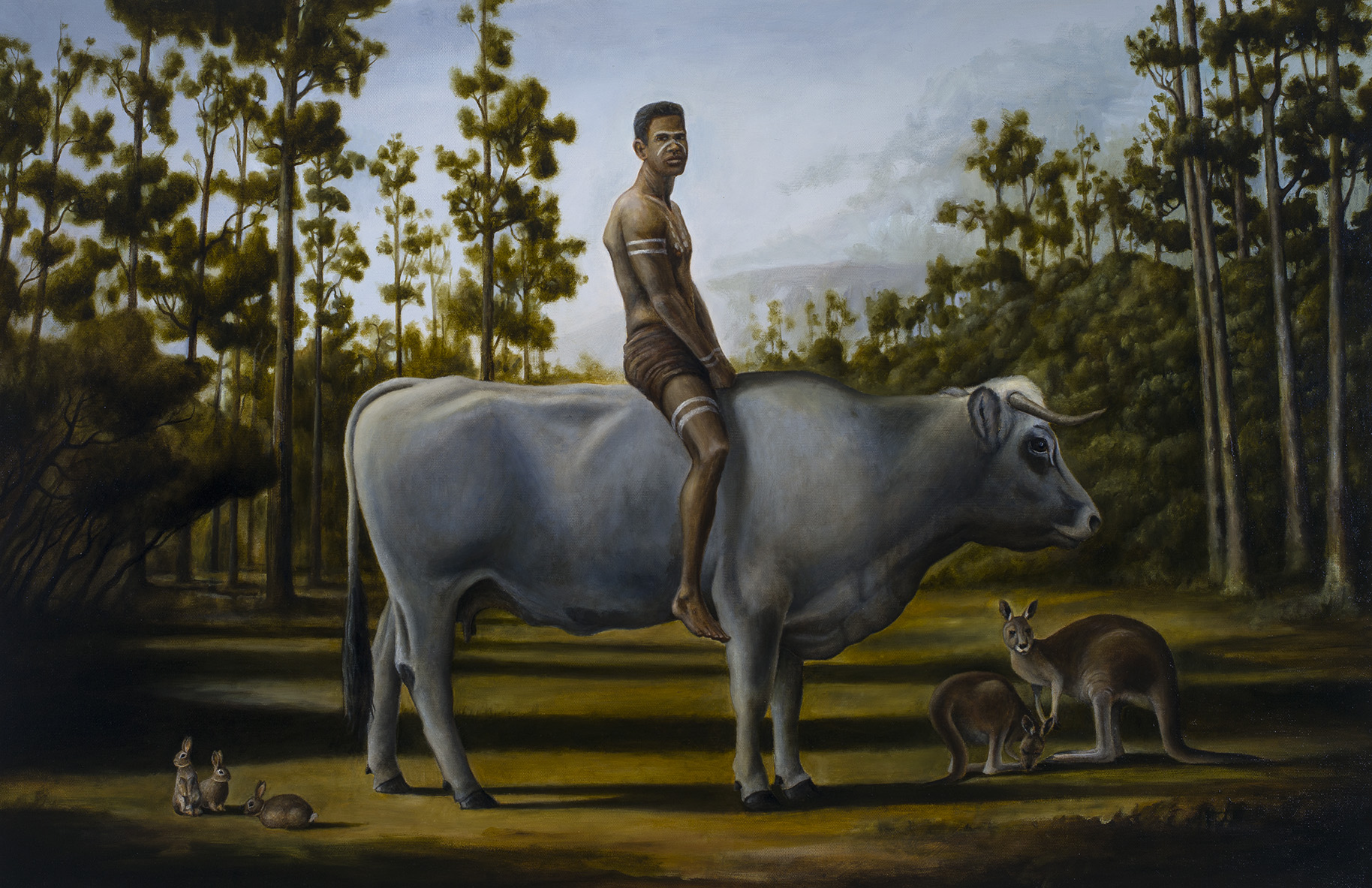

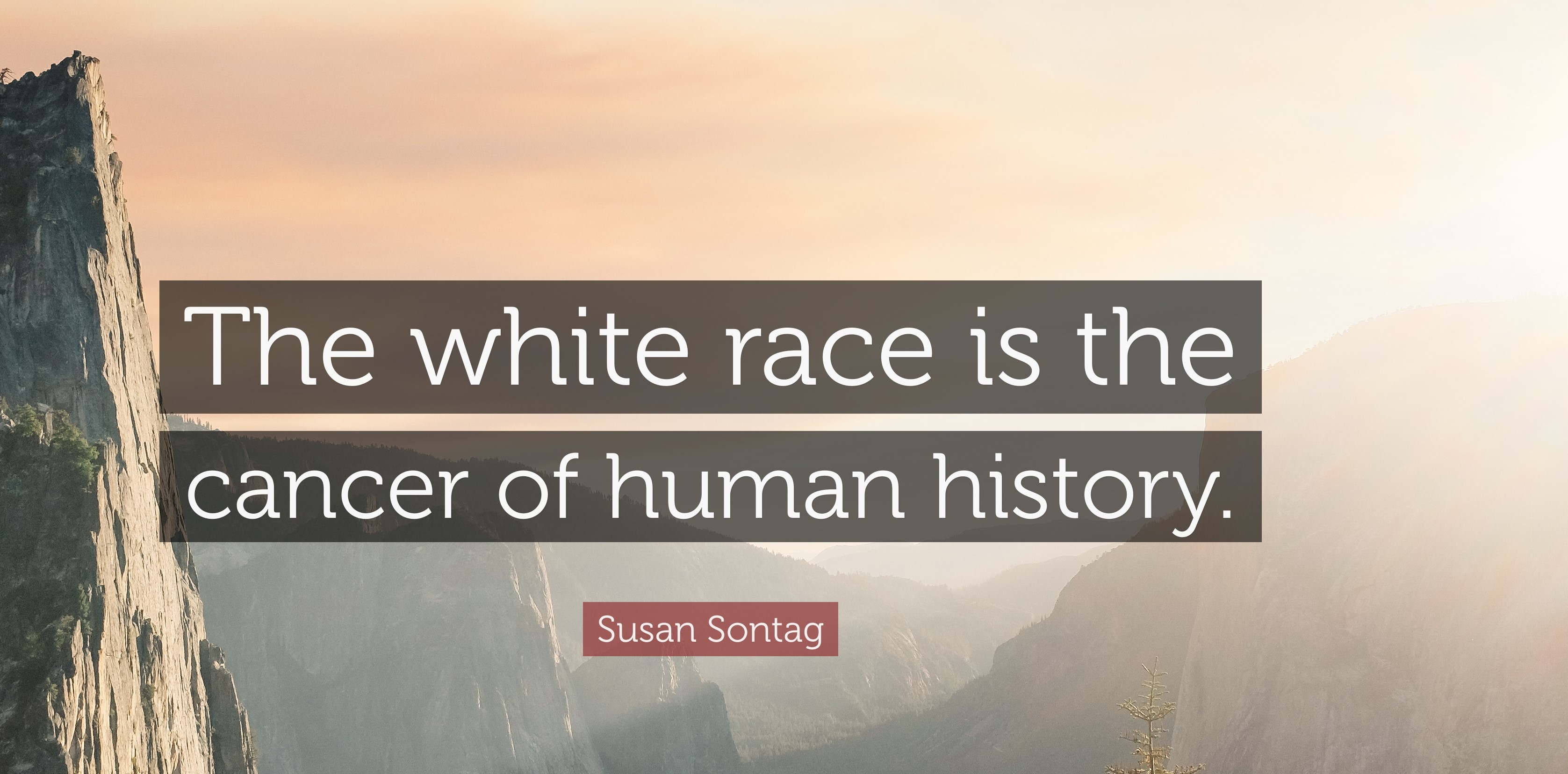

Out of anti-colonial sentiments of such Third World intellectuals as Fanon and their colleagues from Western countries, there grew natural animosity to the West, which was responsible for colonialism, and the idealization of non-Western societies as the holders of a revolutionary potential and better forms of life. The fact that in the 1950s and the 1960s, the West was involved into two bloody colonial wars (France in Algeria, and the United States in Vietnam) amplified those sentiments. As a result, since the 1960s, for the left, the major existential enemy was shifting from capitalism as an economic system to Western civilization that was associated with colonialism, consumerism, and moral decay. In 1966, writer Susan Sontag conveyed well that negative attitude, which was becoming part of the intellectual mainstream, by saying that the white West was the “cancer of human history.”

There was now much talk on the left about humans being enslaved and alienated by the technology-driven individualistic civilization of the West and less talk about an economic growth, progress, and capitalism robbing workers of a surplus value. In fact, economic progress became a curse phrase. The idealization of the non-Western, tribal, and the primitive became a natural intellectual offshoot of such ideological pursuits. Reflecting on the cultural turn that was launched in the 1960s, Marxist sociologist Harold Bershady stressed that this trend carried obvious reactionary notions: “It was a kind of left-wing conservatism.” Gradually ditching the failed argument of the old left, who had insisted that capitalism had been profoundly inefficient and could not provide material affluence, the New Left were switching to the moral and cultural critique of that very affluence that now was declared a major vice. Sontag again spelled out this message in her flamboyant style: “America is a cancerous society with a runaway rate of productivity which inundates the country with increasingly unnecessary commodities”; in an ironic twist, such utterances turned out to be Freudian slips: the writer died from cancer.

Ayn Rand, a rising countercultural icon on the right who, in contrast to the Marxist ultimate proletarian “savior,” invented her own version of a “noble savage” in a form of heroic capitalist “savior” entrepreneur, responded to those sentiments with a loaded sarcasm: “The old-line Marxists used to claim that a single modern factory could produce enough shoes to provide for the whole population of the world and that nothing but capitalism prevented it. When they discovered the facts of reality involved, they declared that going barefoot is superior to wearing shoes.” Among others, unnecessary commodities included TV sets, comics magazines, soap operas, the variety of household items. Incidentally, in the 1970s and the 1980s, such romantic neo-primitivist attitudes helped the left to find a common ground with environmentalists who began to preach an apocalyptic vision of the global collapse of natural habitat if not arrested by massive government regulations.

Conclusions

The frustration with the economic growth and the incorporation of the non-Western ones and radical environmentalism into the socialist agenda was a natural offshoot of the “going primitive” trend that looked beyond Europe and North America for major revolutionary hubs. Exorcising the proletarian messiah class from the popular Marxian socialism and moving toward identity and the idealization of non-Western “others” was not a straight-forward process. In the 1960s-1970s, among the New Left, communist dissidents, and Trotskyite fossils, there was still a desire lingering on to somehow continue the revolutionary elan of the proletariat. At the same time, among those elements one could detect the growing trend toward romancing the working-class culture and its “organic” anti-bourgeois ways. The Birmingham School of Cultural Studies and dissenting communist historians such as E. P. Thompson, who aspired to cleanse Marxist theory from economic determinism and who elevated the proletarian culture and consciousness, prepared a fertile intellectual ground for the later cultural turn in the left thought collective.

Before the current left completely ditched the working class from the pedestal and developed a an “acute identity syndrome,” the New Left segment acted as an intellectual bridge between classical Marxian socialists and the current identitarian left. In the 1960s and the 1970s, the New Left gradually transferred the metaphysical characteristics ascribed to the proletariat to the non-Western “others,” domestic people of “color,” chronically unemployed, social deviants, women, and gays. Communist bohemian historian Hobsbawm with his bookish “social bandits” and his attempts to probe Latin American peasants for their revolutionary potential is an excellent snapshot of how that process was unfolding.

Just like the proletariat of the old, the new victim groups were thought to become the oppressed redeemers – the new “noble savages” of the left. On the one hand, such revision of traditional Marxism gave an opportunity to the New Left to disentangle themselves from the Old Left. Yet, on the other hand, this very revisionism allowed them to continue the familiar Marxist tradition in the new intellectual garb. The new groups designated to the role of the oppressed ones were lumped together in an abstract category of the poor and disadvantaged. In the same manner, old Marxism generalized about the proletariat as a homogenous impoverished class, downplaying ethnic, religious, and economic differences within this group.

In the 1960s, the most passionate New Left revisionists who became hooked on the Mills’ message of bashing the “Victorian Marxism” cast the newly found surrogates into authentic, uncorrupt and holistic people, the caretakers of the egalitarian ethics and natural goodness. Thus, in a religious-like manner, New Left activist Casey Hayden, the spouse of famous Tom Hayden, described her feelings about the new “chosen ones”: “We believed that the last should be the first, and not only should be the first, but in fact were first in our value system. They were first because they were redeemed already, purified by their suffering, and they could therefore take the lead in the redemption of us all.” Another New Left writer characteristically titled his book about “unspoiled” and “authentic” rural blacks in Mississippi A Prophetic Minority (1966).

Those conservative and libertarian authors who are fixated on the Frankfurt School have failed to pinpoint the variety of intellectual fountainheads that contributed to the cultural turn. So have those in the current left mainstream who downplay their genetic links with Marxian socialism. Besides the Frankfurt School, there were other essential intellectual sources on which the left heavily drew when refurbishing their political religion in the 1960s and the 1970s. This essay has highlighted the role of the British “cultural Marxists” as well as their intellectual predecessors and contemporaries who “racialized” Marxism. Moreover, because of the worldwide hegemony of English language, the writings of C.L.R. James and William Dubois, popular translations of Frantz Fanon, and British Cultural Studies along with New Left Review played more important role in fomenting the cultural turn than the often-spoken Frankfurt School. In fact, it was NLR that popularized “frankfurters’” writings that regular educated readers had a hard time to digest.

The names and schools profiled in this essay do not exhaust other potent sources of the cultural left, which still await their comprehensive study. For example, a future researcher cannot bypass secularized Protestantism of northern Europe and North America and its links with the current woke culture. It is impossible to reduce the virulent and aggressive moralism of the current secular social justice warriors, the Unitarian Universalist movement, and several other progressive Protestant denominations in the United States to the intellectual evolution of Marxian socialism in the direction of identity matters. Although many of the above-mentioned elements have been feeding on the New Left neo-Marxist writings, they obviously drew too on the secularized Puritan tradition that, according to famous H. L. Mencken, had been always haunted by the “fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy.” In Multiculturalism and the Politics of Guilt: Towards a Secular Theocracy (1992), Paul Gottfried briefly outlined how via the social gospel tradition, radical Puritanism of some Protestant denominations gradually mutated into virulent cultural moralism and how in the current “theology” of the left, the old Christian concept of sin and salvation became replaced with sensitivity training and social therapy sessions. Most important, we need to keep in mind that British Cultural Studies, dissenting Marxist intellectuals who idealized working class anti-bourgeois culture, Mills and the American New Left, the Frankfurt School, and the latter-day social justice “evangelicals” cross-fertilized each other, spearheading what later produced the identitarian woke tradition, which currently represents the progressive mainstream.