Since first dipping my feet (brain?) into philosophical waters I’ve realized that the world has more dimensions than my mind. Many more. Which means insisting on a consistent philosophy is, in all likelihood, a recipe for disaster.

This isn’t to say I’ve got an inconsistent philosophy, or that I’m ready to throw up my hands and say “anything goes!“. But like a good bridge, my philosophy is full of tensions.

I can’t derive everything back to the Harm Principle (a principle I like), recognition of subjective values (which I’m on board with), or some notion of a social utility function (which I do like as a rhetorical crutch or skyhook, but am unwilling to take with me more than arm’s length from the whiteboard).

Instead, I’ve got a smorgasbord of mental tools–ethical notions (“don’t kill people!”), social science models (prisoners’ dilemma, comparative advantage)–that I try to match appropriately to the situation.

This puts me in the unfortunate position of requiring a great deal of humility. But as it will say on my tombstone: worse things have happened to better people…

I approach the world with libertarian priors. At the end of the day, I’m a left-libertarian anarchist. But Jonathan Haidt’s work has convinced me that my priors say more about me than the world. To be sure, libertarianism brings something important to the table, but so do other views.

Recognizing the importance of ideological pluralism lets me use my ideology like a lever instead of a bat–a tool instead of a weapon. And hey, what’s more libertarian than pluralism?!

As a centuries-long-run prospect for a meta-utopia I’m still staunchly libertarian. Go back in time 500 years and you’ll be told democracy is a pipe dream. I think we’re in a similar moment for the ideas of radical freedom, self-determination, and decentralization of power I’d really like to see put into practice. But imagine going back in 500 years, convincing everyone you’re a powerful wizard, then implementing democracy all at once. I don’t think it’d work out very well. Hell, I’m not even sure about going back in time 3 years to run that experiment! Similarly, flipping the An-Cap switch tomorrow would probably be 100 steps forward, 1000 steps back. Without the appropriate culture in place, good ideas are likely to backfire.

Still, I’m a libertarian anarchist by default and want to see the world move in that direction. But in the short-medium run I refuse to be dogmatic.

I get a lot out of my ideological priors, but I get more by refusing to slavishly follow them at all costs. Yes, the greatest good will be served in an anarcho-capitalist world (I think). But it’s a long trip from here to there. Sustaining that equilibrium will require a cultural shift that hasn’t happened yet–and ignoring those informal institutions is likely to lead to something more like feudalism than utopia. In the mean time, I say move towards greater freedom and avoid getting bogged down in partisanship.

So I’ve got a long-run goal: radical federalism and maximal freedom. But how do we get there? What are the short- and medium-run goals?

Simply to make things better while encouraging people to engage in voluntary interactions that create value, especially by building up social capital networks.

My Austrian-subjectivist priors are in tension with my rationalist-utilitarian instinct. But I think we find a way out by considering policy effects on future generations. Tyler Cowen suggests pursuing policy that promotes long run economic growth.

The big caveat is that although GDP is the best available metric to pursue, GDP is an imperfect measure. Figuring out “GDP, properly understood” adds a layer of complexity that makes policy evaluation all the more difficult. Which is part of the controversy with my recent posts on pollution taxes.

For example, after the end of slavery, total leisure time increased which would decrease measured GDP. But clearly a proper accounting of productivity would discount the initially higher GDP by the cost of forced labor. Similarly, we have to refine our notion of measured* economic well-being to account for things left out of the old methods–like household consumption, leisure, black markets (side note: the war on drugs is a waste!), human capital**, and ecological assets that fall outside the private property system.

Addendum for the left: what’s best for the world’s poorest people is a worthy addition to Cowen’s policy. And it’s an addition that also tends to push us towards libertarian arguments (like liberalization of immigration policy).

Unfortunately, I’m a rationalist by default which means I have to work at my epistemic humility. I’m constantly tempted to see the world as more legible than it really is. I have to keep reminding myself that I don’t know could fill a library. But the world is much more complex than any functional team of smart people could handle, let alone a lone economist–even if he happens to be one of few who really do get it.

One of my favorite arguments is the Austrian-libertarian point that “if we knew what people would do with their freedom, we wouldn’t need it.” For example, the reason to allow someone to start new businesses isn’t because we know that it’s going to make things better. Instead, it’s because market innovation depends on decentralized, crowd-sourced experimentation. We don’t say “oh, this Steve Jobs guy is about to improve our lives,” because if we could do that (we can’t) then we could instead find a less costly way to get the same outcome (we can’t do that either).

This line of reasoning also applies to policy. There are some easy cases–there’s plenty of low-hanging fruit in occupational licensing. But society is a complex system, so you can’t do just one thing. Any one policy change ripples through the system and creates unintended consequences.

Don’t get me wrong, I’m not saying we should do nothing. But my conservative friends are right that we shouldn’t go too fast. In any case, we’ve got more tensions that require me to listen to a wider range of ideological voices due to my cognitive limits.

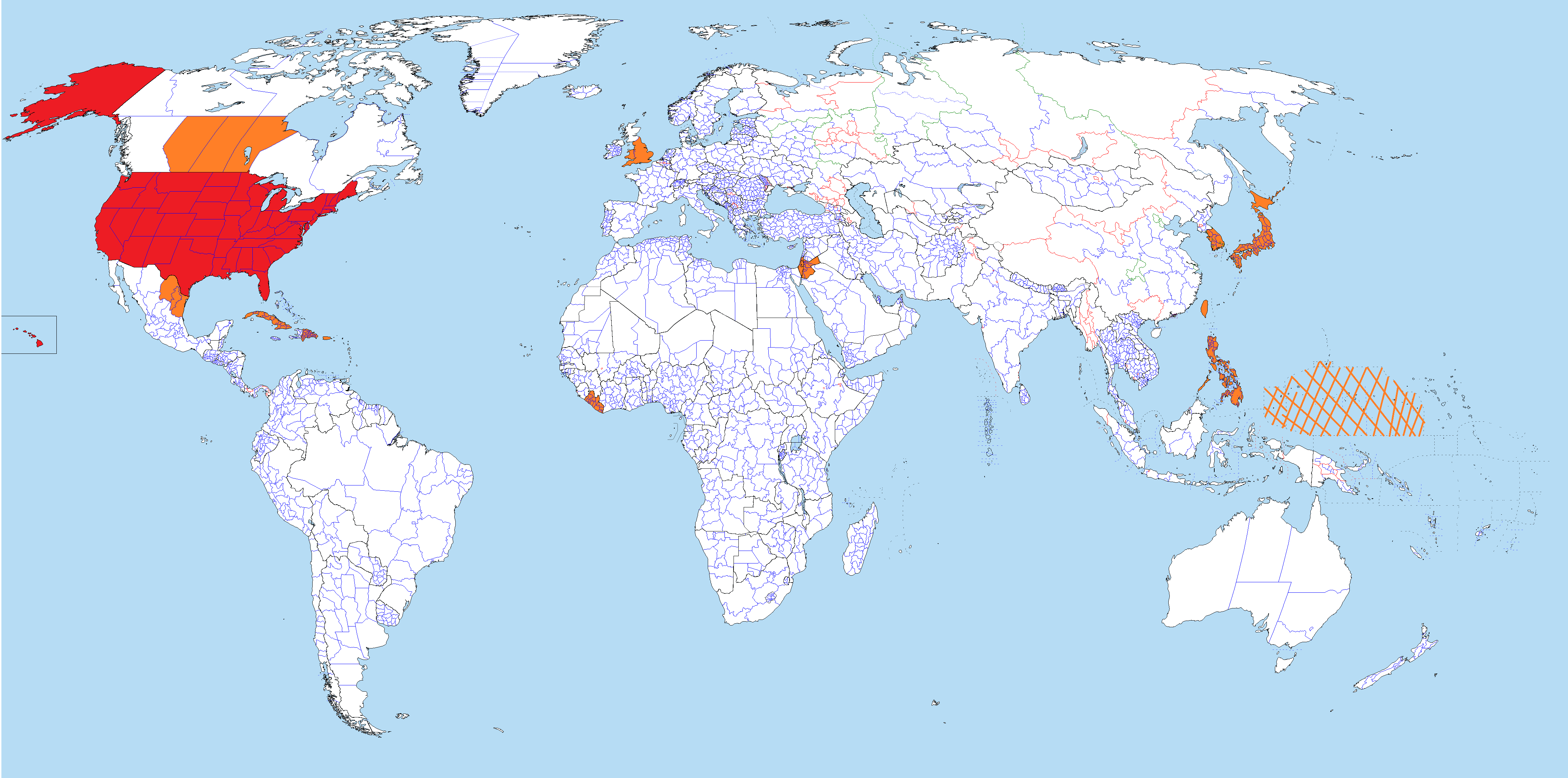

A particularly interesting policy question is to what extent we should (not) take account of the impacts of American (Canadian, European, Chinese, etc., etc.) policy on non-Americans.

Here we find another tension. On the one hand, surely being accidentally born into a particular geography doesn’t give you greater moral weight than others. On the other, even if we want American policy to help Haitians, there’s a knowledge problem exacerbated by distance.

I think the appropriate response is a friendly and open federalism. Local issues should be handled locally. We should be neighborly. We should resist the temptation to centralize power.

But we should also take advantage of large-scale governance structures (private or public) to deal with large-scale issues. Match the scale of governance to the scale of the relevant externalities.

The downside of this approach is that some locales will do terrible things. “States’ rights” is a bad argument for slavery (or for anything else). But stepping in to make things better isn’t an unambiguous improvement. If there’s one thing to learn from America’s adventures in statecraft*** it’s that you can’t just force a country to be free.

Given that, we should be more open to accept the world’s huddled masses yearning to breathe free. Historically, our record is far from spotless. But there have also been humanitarian successes in moving people away from tyranny.

We have a moral obligation to at least consider the well-being of everyone around the globe. And the lowest hanging fruit for actually making a positive difference is opening up our borders. Not to say there’s a simple answer, but the answer lies in the direction of freedom of movement.

How should we (according to me) go about deciding questions of public policy? We should opt to encourage the creation of value and reduction of costs (i.e. economic growth). But we should do so carefully and with open minds.

GDP growth is a worthy goal, but not for it’s own sake. John Stuart Mill wrote:

“How many of the so-called luxuries, conveniences, refinements, and ornaments of life, are worth the labour which must be undergone as the condition of producing them?… In opposition to the ‘gospel of work,’ I would assert the gospel of leisure, and maintain that human beings cannot rise to the finer attributes of their nature compatibly with a life filled with labour.”

Mindless insistence on measurable output overlooks important things like going to your kid’s little league game, grabbing a beer with friends, or quiet contemplation. And even if the people arguing for protecting the environment seem a bit silly, we’re wrong to ignore the importance of environmental externalities in affecting our standard of living. All of which is to say, Cowen is right that we need to carefully consider the shortfalls of how we measure economic growth, all while encouraging it.

Perhaps most importantly, we should relish a tension between consequentialism and principles. There are plenty of low-hanging fruits for libertarianism, but if we want to get the most out of this metaphorical tree we need to let a fear of bad outcomes encourage us to invest in civil society, informal institutions, and rich social networks so that freedom can expand without costing us inhumanity. I want to see the welfare state ended, but I’m willing to wait while we start by reducing barriers to entrepreneurship. I want to see taxes go away, but I’m willing to see a less-bad tax replace an egregious one.

We should reject the dogmatism that too often leads us to over-prioritize ideological purity. First, such purity can trap us in local optima (metaphor: a self-driving car programmed to never go east sounds like a good way to get from NYC to LA… till it gets stuck in a cul de sac somewhere). Second, that purity is an illusion. God’s true ethical system simply isn’t available to us–it’s more complex than our brains are–so why worry?

Post script: don’t take this to be an argument against libertarianism. Or a call to prioritize “pragmatism” over ideology or any other political values. I’m not trying to make a definitive argument abolishing ideology, I’m just gently pushing back. The key word here is tension. We can’t have tension between A and B if we get rid of A.

*Here’s another tension: I don’t believe we can actually measure economic well-being. I think we can make educated guesses based on well-thought out studies of observable proxy variables, but I believe in the impossibility of interpersonal utility comparison.

**A major pet peeve of mine is the conflation of education and schooling. Education, properly understood, is simply not measurable. We might find some clever proxy variables (for example, the Economic Complexity Index is my current favorite metric for productive capability–which overlaps capital and human capital accumulation).

***That’d be a good title for a comic book! If you know the right historian and/or international relations scholar, put them in touch with Zach Weinersmith!