This article is part of a series on bitcoin (and bitcoiners’) arguments about money and particularly financial history. See also:

(2): ‘Rothbard’s First Impressions on Free Banking in Scotland Were Correct’, Joakim Book, AIER (2019-08-18)

(3): ‘The Harder Money Wins Out’, Joakim Book, NotesOnLiberty (2019-08-19)

(4): ‘Bitcoin’s Fixed Money Supply Is a Weakness’, Joakim Book, AIER (2019-08-28)

It is unfair to expect technologically savvy bitcoiners to also be apt and well-read monetary economists. By no means do the skills and experiences of either have to overlap. Through the rise of Bitcoin with its explicit central banking challenge and attempt to become a worldwide currency, the subject matter of the two groups has unexpectedly clashed. All arguments that support or attack bitcoin is a head-first dive into monetary economics – sometimes exhuming centuries-long disputes among monetary economists and often blatantly distorts and overlooks money and banking arrangements of the past.

We can’t have that, can we.

One of the most delightful events in the libertarian world is the monthly Soho Forum debate run by Gene Epstein. Yesterday’s splendid showdown between Profs. George Selgin and Saifedean Ammous on the suitability of Bitcoin as a Medium of Exchange is bound to get some serious traction once the recording is on available only – look out for that!

A great debate for anyone interesting in monetary system and monetary economics more generally, this was probably the best and most entertaining of many Soho Forum debates I’ve watched. It’s a good format that forces speakers to engage and respond to one another’s arguments, which makes a two-hour conversation on something as technical and intricate as Bitcoin’s monetary role an absolute delight; even those of us deep into this nerdy rabbit hole can learn a lot and walk away with a trove of inspiration.

Channeling that inspiration into long-form, multi-part reviews of the relevant financial and monetary history is exactly what I’m going to do!

One question I often get regarding my research interests (banks, money and financial markets in the past) is the mildly offensive but absolutely correct question to ask: who the f— cares?! Bitcoin and the question of monetary regimes are perfect examples that make financial history relevant: the rise of crypto questions the fundamentals of monetary systems, systems that very rarely change. Naturally, the financial historian has an edge here, having a lot more nuanced knowledge about past monetary and financial arrangements and their operations. History becomes our (only) laboratory, to which the financial historian typically has a lot to contribute.

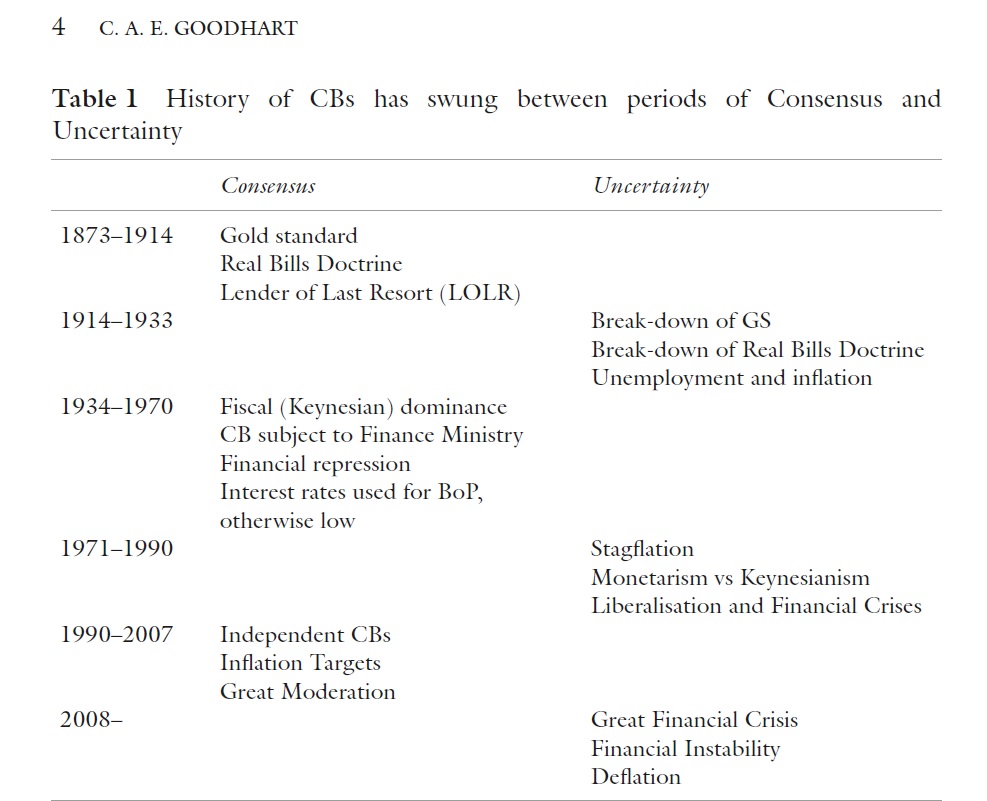

Moreso than other topics, fundamental questions of monetary regimes are explicitly pitted against other possible regimes – by their nature comparative and always informed by historical experience. It takes about two-and-a-half sentences before debates over money invoke some reference to financial and monetary history – as they should, since they illustrate how some (aspect of) a different monetary regime worked. Frustratingly enough, there’s a good chance that the speaker has mindboggingly little idea of what s/he’s talking about!

That’s where I like to come in. To a roomful of aspiring monetary economists at Cato’s Alternative Money University in July this year, Randall Wright‘s response to why he does monetary economics at all (“to debunk all this B-S!”) generalizes pretty well.

I’m gonna use this post to review some of the mistakes Saifedean made yesterday – and use it going forward as an updated collection of future posts on the topic, especially as I go through Saif’s promising book, The Bitcoin Standard: The Decentralized Alternative to Central Banking. The aim here is to respectfully clarify the parts of the Bitcoin arguments where I’d like to think that I have a comparative advantage – financial and monetary history – and to better develop my understanding of the monetary theory involved.

Here are some points that came up yesterday:

- The Monetary Progression of ‘Harder Money’: the brilliance of the past is that almost any account, no matter how persuasive and compelling, is bound to run into inconvenient historical facts. The world is more nuanced than can be reasonably captured by pithy generalization (yes, I realize the irony here). In a piece attacking this bitcoiner’s creation myth earlier this year, I wrote:

This progressively upward story is pretty compelling: better money overtake worse money until one major player unfairly took over gold – the then-best money – replacing it with something inferior that the Davids of the crypto world now intents to reverse. […] Too bad that it’s not true. Virtually every step of this monetary account is mistaken.

- The Lender-of-Last-Resort role privately provided: Many Austrians and opponents to fractional reserve banking routinely believe that banks holding less-than-100% reserve against their deposits must have a government backing them, providing emergency liquidity when such banks are inevitably run upon. This is completely false. I can point to many different historical instances that privately accounted for such risks, from private clearinghouses to insurance, to the option-clause debate in Scottish Free Banking and contingent/unlimited liability institutions.

- …which leads us to Scottish Free Banking. There’s a famous quip by Rothbard (“Rothbard’s Law“) that describes the tendency for economists to specialize in the fields they’re worst at: Henry George specialized in land, where his writing is appalling; Milton Friedman on Money, where he’s awful etc. I usually say that the same thing applies for Rothbard whenever he writes on Financial History. Very bad. And yes, I will go through his article ‘Myth of Free Banking in Scotland’…

- Saif made a distinction yesterday between the “Medium of Exchange” and the “Payment Mechanism” involved that struck me as misleading, and I didn’t get a chance to finish my reasoning with him in person – so I’ll flush it out in a piece later on. Happily for all you Free Banking fans, it involves note-issuing Scottish banks and the bigger questions of redeemability and outside/inside money.

Some additional housekeeping from yesterday:

- Saif: “There was no real estate bubble on the Gold Standard”.

- Yes, Selgin said, the Florida 1920s housing bubble leading up to the Great Depression. No, Saif correctly objected, that wasn’t a real gold standard, but a central bank-planned Gold Exchange Standard.

Ok, fine – I’d agree with Saif here. How about the 1893 Australian banking crisis? Classical Gold Standard, no central bank, but a property boom and bubble-like collapse nonetheless. - A response might be “but fractional reserve banking!” but a) that’s a topic I’ll delve into much more, and b) this is started to sound like a No True Scotsman fallacy…

- Yes, Selgin said, the Florida 1920s housing bubble leading up to the Great Depression. No, Saif correctly objected, that wasn’t a real gold standard, but a central bank-planned Gold Exchange Standard.

- Saif: “Central banks hold gold – they don’t trust each other enough to hold currency”

- Saif probably misspoke here, since he couldn’t possibly believe this; looking at any central bank’s balance sheet would instantly dispell such beliefs. Central banks generally hold no more than 5-8% of their assets in gold, and often a lot more than that in foreign currency-denominated asset. The ECB holds about equal parts (7-8% of assets) in gold and foreign currency. I routinely follow the weekly changes in the Riksbank’s balance sheet and even after a more extreme QE programe than the Fed’s (as % of GDP), it holds more FX than it does SEK-denominated assets (and no more than 5% in gold). The Bank of England technically doesn’t actually have any gold at all on its balance sheet, but holds gold in storage at its vaults (on behalf of other countries and the UK Treasury).

Bear with me over the next few months, as I make my way through Saif’s book and engage with these thrilling debates. Feel free to interrupt/comment on Twitter at any point if you think I’ve made a factual/empirical error, error in reasoning or in relevance to Bitcoin.

And yes, keep in mind that this is a respectful inquiry into fascinating topics with people who agree on like 92% of everything. Feel free to call me out for unnecessarily snarky and offensive thing as we go along – and welcome to the party!