Politicians, pundits and activists jumped on a new literature that asserts that there no negative effects of substantial increases of the minimum wage on employment. Constantly, they cite this new literature as evidence that the “traditional” viewpoint is wrong. This is because they misunderstand (or misrepresent) the new literature.

What the new literature finds is that there could be no significant negative effects on employment. This is not the same as saying there are no negative effects overall. In fact, it is more proper to consider how businesses adjust to different-sized changes by using various means. Once, the minimum wage is seen in this more nuanced light, the conclusion is that it still bites pretty hard.

The New Minimum Wage Literature

Broadly speaking, the new literature states that there are minimal employment losses following increases in the minimum wage. It was initiated twenty years ago by the works of Alan Krueger and David Card who found that, in Pennsylvania and New Jersey, a change in the minimum wage had not led to losses in employment. This caused an important surprise in the academic community and numerous papers have found roughly similar conclusions.

These studies imply that the demand for labor was quite inelastic – inelastic enough to avoid large losses in employment. This is a contested conclusion. David Neumark and William Wascher are critical of the methods underlying these conclusions. Using different estimation methods, they found larger elasticities in line with the traditional viewpoint. They also pointed out Card and Krueger’s initial study had several design flaws. With arguably better data, they reversed the initial Card and Krueger conclusion.

These critics notwithstanding, let us assume that the new minimum wage literature is broadly correct. Does that mean that the minimum wage is void of adverse consequences? The answer is a resounding no.

This is because of an important nuance that has been lost on many in the broader public. In a meta-analysis of 200 scholarly articles realized by Belman and Wolfson, there are no statistically discernable effects of “moderate increases” on employment. The keyword here is “moderate” because the effects of increases in the minimum wage on employment may be non-linear. This means that while a 10% increase in the minimum wage would reduce teen employment by 1%, a 40% increase will reduce teen employment by more than 4%. A recent study by Jeremy Jackson and Aspen Gorry suggests as much: the larger the increase of the minimum wage, the larger the effects on employment.

If labor costs increase moderately, the strategy to reduce employment may be relatively inefficient. The increase of labor costs needs to reach a certain threshold before employers choose to fire workers. Below such a threshold, employers may use a wide array of mechanisms to adjust.

Adjustment channels

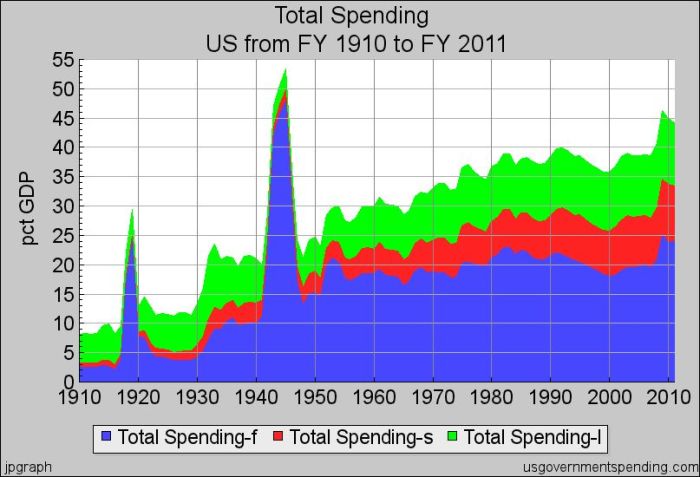

Employers on their respective markets face different constraints. This diversity of constraints means that there is no “unique” solution to greater labor costs. For example, if the demand for one’s products is quite inelastic, labor costs can be passed on to consumers through an increase in prices. While this may not necessarily hurt workers at the minimum wage, it impoverishes other workers who have fewer dollars left to spend elsewhere. This is still a negative outcome of the minimum wage – its just not a negative outcome on the variable of employment.

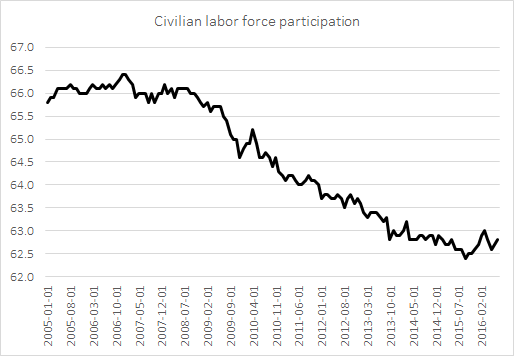

In other cases, employers might reduce employment indirectly by reducing hours of work. This is an easy solution to use for employers who cannot, for a small increase in labor costs, afford to fire a worker. Even Belman and Wolfson – who are sympathetic to the idea of increasing the minimum wage – concede that increases in the minimum wage do lead to moderate decreases in labor hours. More skeptical researcher, like Neumark and Wascher, find that the effects on hours worked is much larger. Again, the variable affected is not employment measured as the number of people holding a job. However, a reduction in the number of hours worked is a clearly a perverse outcome.

Another effect is that employers might reduce expenses associated with their workers. Even Card and Krueger, in their book on the minimum wage, recognize that employers may opt to cut on things like discounted uniforms and free meals. An employer facing a 5% increase in the minimum wage will see his labor costs increase, but firing an employee means less production and lower revenues. Thus, firing may not be an option for such a small increase. However, cutting on the expenses associated with that worker is an easy option to use. This means fewer marginal benefits and on-job training. Employers adjust by altering the method of compensation. For example, economist Mindy Marks estimated that a 1$ increase of the minimum reduced by 6.2% the probability that a worker would be offered health insurance. Again, employers adjust and the effects are not seen on employment. Nonetheless, these are undisputedly negative effects.

The effect may also be observed on the type of employment. Employers may decide to substitute some workers by other types of workers. Economist David Neumark pointed that, subsumed in the statistical aggregate of “labor force” is a shift in its shift. In his article, written for the Employment Policies Institute, he stated that “less skilled teens are displaced from the job market, while more highly skilled teens are lured in by higher wages (even at the expense of cutbacks in their educational attainment)”. Another example could be that a higher minimum wage induces retired workers to return to the labor force. Employers, at the sight of a greater supply of experienced workers, prefer to hire these individuals and fire less-skilled workers. In such case, “total employment” does not change, but the composition of employment is heavily changed. The negative effects are clear though: less-skilled workers are not allowed to acquire new skills through experience.

Conclusion

None of these adjustment mechanisms in response to “moderate increases in the minimum wage” are desirable. Yet, all of these channels would allow us to conclude that there are no effects on employment. To misconstrue the ability of employers to select multiple channels of adjustments other than reducing employment as the proof that the minimum wage has no negative effects is perverse in the utmost. The statement that “moderate increases in the minimum wage has no statistically significant effects on employment” is merely a positive scientific statement with no normative implications whatsoever. If anything, the multiple adjustment mechanisms suggest that the minimum wage still hurts and that is both a positive and normative statement.