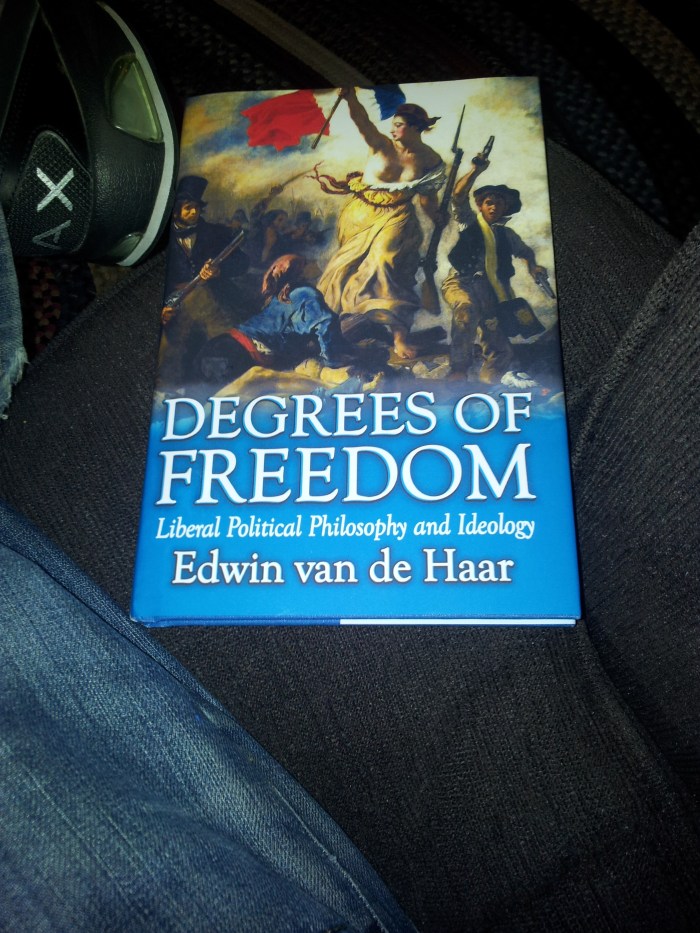

Since the fifteenth century, [the Netherlands] has had several features which later liberal thinkers, such as David Hume and Adam Smith, enviously referred to. Compared to other countries, economic freedom was an important issue, just as the larger degree of religious freedom. Trade, tolerance, and cultural developments turned the Dutch into an early manifestation of liberalism. However, with the possible exception of Erasmus, Spinoza, and perhaps the Rotterdam-born but London-based Bernard Mandeville, the Dutch lacked great thinkers who could provide this liberal practice with a theoretical base.

This is from the introduction (page 2) to Dr van de Haar‘s excellent new book, Degrees of Freedom: Liberal Political Philosophy and Ideology, and I think it makes a good argument in favor of the “common sense” approach to the political. This common sense approach, for those of you wondering, is often contrasted in American libertarian circles with the theoretical approach espoused by academics. Common sense libertarians tend to be more socially conservative and more parochial than theoretical libertarians who, in turn, are less socially conservative and more cosmopolitan in outlook. This difference in outlook between the two factions leads to the former camp appealing to “the people” in arguments, whereas the latter often appeal to the authority of a scholar or school of thought. Dudes like Ron Paul and Lew Rockwell are in the former camp; dudes like Steve Horwitz and Eugene Volokh are in the latter. This is not a tension limited to American libertarians, of course. You can find it just about anywhere, but libertarians have made it interesting, mostly because – once they have acquired facts like the one Edwin reports on above – they ask questions like this:

How is it possible for a society like the Netherlands to exist when it had no great thinkers to claim as its own?

The common sense faction will reply with something like this: “That’s easy: because the Dutch people were left alone they were able to prosper. With no busybody do-gooder class of intellectuals around to make rules for the peons, folks were able to thrive thanks largely to personal freedoms and self-interest.” This line of reasoning has a lot of merit to it. In fact I buy it, even though it’s not complete.

I think the Dutch had plenty of good theorists whose work contributed to the peculiar nature of the 15th century Dutch republic, but it is also true that the high theory of guys like Smith and Hume is largely absent from Dutch political thought (I don’t remember reading any Dutch philosophers in my introductory philosophy courses in college, for example). I can clarify this in my own mind by drawing parallels with American political theorists up until the end of World War 2, when the US suddenly became a superpower and has received a great influx of the Really Smart People from around the world. Like the good Dutch political thinkers, nobody outside of the US knows who James Madison or Alexander Hamilton are (specialists excepted, of course). A few quirky weirdos out there might know who Ben Franklin is, but they won’t know him for his political theory.

Maybe this also had to do with the fact that the Dutch (and American) theorists were more concerned with keeping Spain (or other scheming Great Powers) at bay, and this could only be accomplished with a heavy does of pragmatism to supplement ideals; pragmatism is, of course, something that high theory avoids.

The great thinkers, who we all know (even if we have not all read), in contrast, don’t seem to have a lot of experience in policy and diplomacy. Furthermore, these guys all seemed to be in well-integrated outposts of cosmopolitan empires that were largely populated by minorities. Scotland, for example, was part of the British Empire, or Kant’s Prussia, which was technically independent of the Austro-Hungarian Empire but still very much a cultural and economic junior partner to Vienna at the time.

Here is my big question, though: If the Dutch had no Great Thinkers, how were they able to create the richest, most extensive overseas empire the world had ever seen?

Common sense libertarians, 1

Theoretical libertarians, 0

By the way, my answer to that last question goes something like this: the Dutch, as former subjects of the Spanish Empire, had intimate access to Madrid’s trading networks (cultural access as well as economic and political) and this, coupled with the federal republic that Dutch statesmen were able to cobble together, gave lowlanders just enough breathing room to raise the bar of humanity. Again, you can find Dr van de Haar’s new book here.