Note: This is an old post, reproduced today in honor of American Senator and presidential candidate Bernie Sanders

In the previous installment:

I explained how the general standard of living in America, denoted by real income, grew a great deal between 1975 and a recent date, specifically, 2007. This, in spite of a widespread rumor to the contrary. The first installment touched only a little on the following problem: It’s possible for overall growth to be accompanied by some immobility and even by some regress. Here is a made-up example:

Between the first and the second semester, grades in my class have, on the average, moved up from C to B. Yet, little Mary Steady’s grade did not change at all. It remained stuck at C. And Johnny Bad’s grade slipped from C to D.

Flummoxed by the sturdiness, the blinding obviousness of the evidence regarding general progress in the standard of living, liberal advocates like to take refuge in more or less mysterious statements about how general progress does not cover everybody. Or not everybody equally, which is a completely different statement. They are right either way and it’s trivial that they are right. Let’s look at this issue of unequally distributed economic progress in a skeptical but fair manner.

It’s awfully hard to prevent the poor, women and minorities from benefiting

I begin by repeating myself. As I noted in Part One, it’s too easy to take the issue of distribution of income growth too seriously. Some forms of improvements in living standard simply cannot practically be withheld from a any subgroup, couldn’t be if you tried. Here is another example: Since 1950, mortality from myocardial infarctus fell from 30-40% to 5-8%. (from a book review by A. Verghese in Wall Street Journal 10/26 and 10/27 2013). When you begin looking at these sort of things, unexpected facts immediately jump at you.

Fishing expeditions

The US population of 260 millions to over 300 million during the period of interest 1975-2007 can be divided in an infinity of segment, like this: Mr 1 plus Mr 2; Mr 2 plus Mrs 3; Mr 2 and Mrs3 plus Mr 332; Mr 226 plus Mrs 1,000,0001; and so forth.

Similarly, the period of interest 1975 to 2007 can be divided in an infinity of subperiods, like this: Year 1 plus year 2; year 1 plus year 3; years 1, 2, 3 plus year 27; and so forth. You get the idea.

So, to the question: Is there a subset of the US population which did not share in the general progress in the American standard of living during some subperiod between 1975 and 2007?

The prudent response is “No.” It’s even difficult to imagine a version of reality where you would be right to affirm:

“There is no subset of the US population that was left behind by general economic progress at any time during the period 1975- 2007.”

Let me say the same thing in a different way: Given time and good access to info, what’s the chance that I will not find some Americans whose lot failed to improve during the period 1975 to 2007? The answer is zero or close to it.

This is one fishing expedition you can join and never come back empty-handed, if you have a little time.

Thus, liberal dyspeptics, people who hate improvement, are always on solid ground when they affirm, “Yes, but some people are not better off than they were in 1975 (or in ______ -Fill in the blank.)” The possibilities for cherry-picking are endless (literally).

Everyone therefore has to decide for himself what exception to the general fact of improvement is meaningful, which trivial. This simple task is made more difficult by the liberals’ tendency to play games with numbers and sometimes even to confuse themselves in this matter. I will develop both issues below.

To illustrate the idea that you have to decide for yourself, here is a fictitious but realistic example of a category of Americans who were absolutely poorer in 2007 that they were in 1975. You have to decide whether this is something worth worrying about. You might wonder why liberals never, but never lament my subjects’ fate.

Consider any number of stock exchange crises since 1975. There were people who, that year, possessed inherited wealth of $200 million each, generating a modest income of $600,000 annually. Among those people there were a number of stubborn, risk-seeking and plain bad investors who lost half of their wealth during the period of observation. By 2007, they were only receiving an annual income of $300,000. (Forget the fact that this income was in inflation shrunk dollars.) Any way you look at it, this is a category of the population that became poorer in spite of the general (average) rise in in American incomes. Right?

Or, I could refer to the thousands of women who were making a living in 1975 by typing. (My doctoral dissertation was handwritten, believe it or not. Finding money to pay to get it typed was the hardest part of the whole doctoral project.) One of the many improvements brought about by computers is that they induced ordinary people to learn to do their own typing. Nevertheless, there was one older lady who insisted all along on making her living typing and she even brought her daughter into the trade. Both ladies starved to death in 2005. OK, I made them up and no one starved to death but you get my point: The imaginary typists fell behind, did not share in the general (average) improvement and their story is trivial.

So, I repeat, given a some time resources, I could always come up with a category of the US population whose economic progress was below average. I could even find some segment of the population that is poorer, in an absolute sense, than it was at the beginning of the period of observation. Note that those are two different finds. Within both categories, I could even locate segments that would make the liberal heart twitch. I would be a little tougher to find people who both were poorer than before the period observation and that would be deserving of liberal sympathy. It would be a little tough but I am confident it could be done.

So, the implication here is that when it comes to the unequal distribution or real economic growth you have to do two things:

A You have to slow down and make sure you understand what’s being said; it’s not always easy. Examples below.

B You have to decide whether the inequality being described is a moral problem for you or, otherwise a political issue. (I, for one, would not lose sleep over the increased poverty of the stock exchange players in my fictitious example above. As for the lady typists, I am sorry but I can’t be held responsible for people who live under a rock on purpose.)

Naively blatant misrepresentations

A hostile liberal commenter on this blog once said the following:

“Extreme poverty in the United States, meaning households living on less than $2 per day before government benefits, doubled from 1996 to 1.5 million households in 2011, including 2.8 million children.”

That was a rebuttal of my assertion that there had been general (average) income growth.

Two problems: first, I doubt there are any American “households” of more than one person that lives on less than $2 /day. If there were then, they must all be dead now, from starvation. I think someone stretched the truth a little by choosing a misleading word. Of maybe here is an explanation. The commenter alleged fact will provide it, I hope.

Second, and more importantly, as far as real income is concerned, government benefits (“welfare”) matter a great deal. Including food stamps, they can easily triple the pitiful amount of $2 a day mentioned. That would mean that a person (not a multiple person- household ) would live on $1080 a month. I doubt free medical care, available through Medicaid, is included in the $2/day. I wonder what else is included in “government benefits.”

The author of the statement above is trying to mislead us in a crude way. I would be eager to discuss the drawbacks of income received as benefits in- instead of income earned. As a conservative, I also prefer the second to the first. Yet, income is income whatever its source, including government benefits.

The $2/day mention is intended for our guts, not for our brains. Again, this is crude deception.

Pay attention to what the other guy asserts sincerely about economic growth.

Often, it implies pretty much the reverse of what he intends. In an October 2013 discussion on this blog about alleged increasing poverty in the US, I asked the following rhetorical question:

“Or have Americans’ standard of living only improved as the gap [between other countries and the US] closed?“

I meant to smite the other guy because the American standard of living has only increased, in general, as we have seen (in Part One of this essay posted). A habitual liberal commenter on my blog had flung this in my face:

“….Since 1975, practically all the gains in household income have gone to the top 20% of households…” (posted 10/23/13)

(He means in the US. And that’s from a source I am not sure the commenter identified but I believe it exists.)

Now, suppose the statement is totally true. (It’s not; it ignores several things described in Part One.) The statement says that something like roughly 60 million Americans are richer than they, or their high income equivalents were in 1975. It also says that other households may have had almost stationary incomes (“practically”). The statement does not say in any way that anyone has a lower income in 1975. At best, the statement taken literally, should cause me to restate my position as follows:

“American standards of living have remained stationary or they have improved….”

You may not like the description of income gains in my translation of the liberal real statement above. It’s your choice. But the statement fails to invalidate my overall assertion: Americans’ standard of living improved between 1975 and 2007.

What the liberal commenter did is typical. Liberals always do it. They change the subject from economic improvement to something else they don’t name. I, for one, think they should be outed and forced to speak clearly about what they want to talk about.

Big fallacies in plain sight

Pay attention to seemingly straightforward, common liberal, statist assertions. They often conceal big fallacies, sometimes several fallacies at once.

Here is such an assertion that is double-wrong.

“In the past fifteen years the 20% of the population who receive the lowest income have seen their share of national income decrease by ten percentage points.” (Posted as a comment on my blog on 10/21/13)

Again, two – not merely one – strongly misleading things about this assertion. (The liberal commenter who sent it will assure us that he had no intention to mislead; that it’s the readers’ fault because, if…. Freaking reader!)

A The lowest 20% of the population of today are not the same as those of fifteen years ago, nor should you assume that they are their children. They may be but there is a great deal of vertical mobility in this country, up and own. (Just look at me!)The statement does not logically imply that any single, one recognizable group of social category became poorer in the interval. The statement in no way says that there are people in America who are poor and that those same people became poorer either relatively or in an absolute sense. Here is a example to think about: The month that I was finishing my doctoral program, I was easily among the 20% poorest in America. Hell, I probably qualified for the 5% poorest! Two months later, I had decisively left both groups behind; I probably immediately qualified for the top half of income earners. Yet, my progress would not have falsified the above statement. It’s misleading if you don’t think about it slowly, the way I just did.

I once tried to make the left-liberal vice-president of a Jesuit university understand this simple logical matter and I failed. He had a doctorate from a good university in other than theology. Bad mental habits are sticky.

B Percentages are routinely abused

There is yet another mislead in the single sentence above. Bear with me and ignore the first fallacy described above. The statement is intended to imply that the poorer became poorer. In reality, it implies nothing of the sort. Suppose that there are only two people: JD and my neighbor. I earn $40, neighbor earns $60. In total, we earn. $100 Thus my share of our joint income is 40%, neighbor’s is 60%. Then neighbor goes into business for himself and his income shoots up to $140. Meanwhile, I get a raise and my income is now $60.

In the new situation, my share of our joint income has gone down to 30% (60/60+140), from 40%. (Is this correct? Yes, or No; decide now.) Yet, I have enjoyed a fifty percent raise in income. That’s a raise most unions would kill for. I am not poorer, I am much richer than I was before. Yet the statement we started with stands; it’s true. And it’s misleading unless you pay attention to percentages. Many people don’t. I think that perhaps few people do.

My liberal critic was perhaps under the impression that his statement could convince readers that some Americans had become poorer in spite of a general (average rise) in real American income. I just showed you that his statement logically implies no such thing at all. If he want to demonstrate that Americans, some Americans, have become poorer, he has to try something else. The question unavoidably arises: Why didn’t he do it?

Was he using his inadequate statement to change the subject without letting you know? If you find yourself fixating on the fact that my neighbor has become even richer than I did because he more than doubled his income, the critic succeeded in changing the subject. It means you are not concerned with income growth anymore but with something else, a separate issue. That other issue is income distribution. Keep in mind when you think of this new issue that, in my illustration of percentages above, I did become considerably richer.

Liberals love the topic of unequal progress for the following reason:

They fail to show that, contrary to their best wish, Americans have become poorer. They fail almost completely to show that some people have become absolutely poorer. They are left with their last-best. It’s not very risky because, as I have already stated, it’s almost always true: Some people have become not as richer as some other people who became richer!

Policy implications of mis-direction about income growth

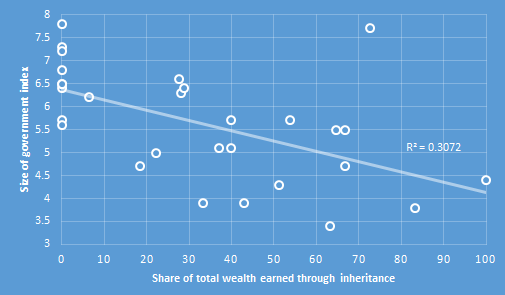

The topic matters because, in the hands of modern liberals any level of income inequality can be used to call for government interventions in the economy that decrease individual liberty.

Here are a very few practical, policy consequences:

A Income re-distribution nearly always involves government action, that is, force. (That’s what government does: It forces one to do what one wouldn’t do out of own inclination.) That’s true for democratic constitutional governments as well as it is for pure tyrannies. In most countries, to enact a program to distribute the fruits of economic growth more equally it to organize intimidation and, in the end, violence against a part of the population. (For a few exceptions, see my old but still current journal article: “The Distributive State in the World System.“ Google it.) This is a mild description pertaining to a world familiar to Americans. In the 1920s, in Russia, many people (“kulaks”) were murdered because they had two cows instead of one.

Conservatives tend to take seriously even moderate-seeming violations of individual liberty, including slow-moving ones.

B Conservatives generally believe that redistribution of income undermines future economic growth. With this belief, you have to decide between more equality or more income for all, or nearly all (see above) tomorrow?

It’s possible to favor one thing at the cost of bearing the travails the other brings. It’s possible to favor the first over the second. This choice is actually at the heart of the liberal/conservative split. It deserves to be discussed in its own right; “Do your prefer more prosperity or more equality?” The topic should not be swept under the rug or be made to masquerade as something else.

If you are going to die for a hill, make sure it’s the right hill.

PS: There is no “income gap.”