- Egypt banned the sale of yellow vests. Are the French protests spreading? Adrián Lucardi, Monkey Cage

- Castro’s Revolution on Its 60th Anniversary Vincent Geloso, AIER

- Americans Are Losing Faith in Free Speech. Can Two Forgotten Philosophers Help Them Regain It? Bill Rein, FEE

- Do Congresswomen Outperform Congressmen? Tyler Cowen, MarginalRevolution

France

The Yellow Vests Movement in France

President Macron spoke to the French nation today (12/10/18). He apologized a little for his figurative distance from the rank-and-file. Then he tried to buy some off the yellow vests off with other people’s money. The national minimum monthly wage will rise by about US$113; overtime will not be taxed anymore. You are not going to believe the next appeasement measure he announced. I have a hard time believing it myself but I read it and heard it from several sources. President Macron decreed a significant Christmas bonus for public servants and ordered (I think) private employers to follow suite. The bonus will also be tax-free. I have no idea what effects these measures will have. I suspect the weather has more influence on the yellow vests’ behavior.

The movement began, as most Americans know by now, as a protest against a new extra tax on diesel fuel. It was presented a little breathlessly as a way to save the planet. This is significant in several ways. First, it suggests that a large fraction of the French people do not believe in climate change (like me) or do not care about it. Second, it demonstrates that Mr Macron, probably along with the political class in general, have lost touch with much of their electorate for not realizing the these perceptions. Third, it shows sheer incompetence if not cynicism. Any average thinking person in France could have warned Mr Macron that a tax on diesel is one of the most regressive taxes possible. The transport of ordinary goods in France relies largely on diesel-powered trucks. A tax on diesel proportionately (proportionately) hits the poor more than the prosperous. Perhaps the government thought that those affected were too stupid or too passive to protest.

The government has reversed its decision on the diesel tax but it’s too late. It seems to me the diesel tax was simply a case of the straw that broke the camel back. Fifty years ago, the French gave themselves a wonderful cradle-to-grave summer camp. It’s a real good one, I must say, including a sort of winter camp of free ski vacations for children. (Would I make this up?) This was based on the original idea that “the rich” could be taxed into paying for summer camp. (Sounds familiar?) After two generations, the bills are finally coming due. The definition of “the rich” has been going down fast. Indirect (and therefore regressive) taxes are everywhere. The increase in the tax on diesel was just one of the latest.

The providential and fun state has other consequences. The main one is that it is implicitly anti-business. It protects employees almost completely against being laid off. It’s solicitous of their leisure with a 34 hour week and many many vacations and holidays. French governing circles have become used to celebrating GDP growth rates so low they are considered shameful in America. I think it’s rigorously true that in the past twenty years, unemployment has never gone below 8%. It’s normally been closer to 9% and even 10%. It’s 20% if you are young. I am guessing (guessing) that it’s 40% and up if you are young and your name is Mohammed.

There is worse. In a pattern that will seem familiar to many Americans, there is a big well-being divide between the capital, Paris proper, and the rest of France. Parisians live in a low-density city with good public transport and many employment opportunities. Housing prices and rents are high in Paris, as you might expect. In nearly all of the rest of France, there are few jobs, spotty services. (I am told it’s not uncommon to have to drive 2 hours each way to consult a specialist); hospitals are good but far and few. Many of those charming villages you see from the freeway have not had schools for many years. Housing in the hinterland is cheap. Of course, this is enough to cause people of low means to be stuck where they are.

It’s difficult for foreign reporters to understand the yellow vests movement, for a small reason and for a big one. First, it does seem to be originally a genuine grassroot movement. Accordingly, it has no leaders and not authorized spokespersons. Second, and much more importantly, in my lifetime the very conceptual vocabulary of market economies has vanished from the public discourse. The yellow vests interviewed on television do not know how to express what hurts them. When ordinary French men and women, and what passes for their intellectual elites, discuss, or even think, about economic problems the only tools they have at their disposal is the pseudo-Marxist vocabulary of those who got their Marxism from Cliff Notes (if that). I think there is only one small French group (on Facebook) that is able to evade this conceptual tyranny. In France, thinking in terms of vaguely socialist terms has ceased to be a choice. It’s now a monolithic social and intellectual reality.

I don’t see how even a more determined and more talented political leader than Mr Macron can tell the great mass of the French people: Summer camp is over; everybody go home and learn to make do with less free stuff. Then, re-learn work.

With all this, France is a functioning democracy. The French elected Macron after six years of disastrous “Socialist” Party rule. Perhaps, as has been the case before, the French people -with their historical inability to reform- will be the canary in the mine for everyone else: The big generous state based on taxation is bad for you or for your children. Just ask the French.

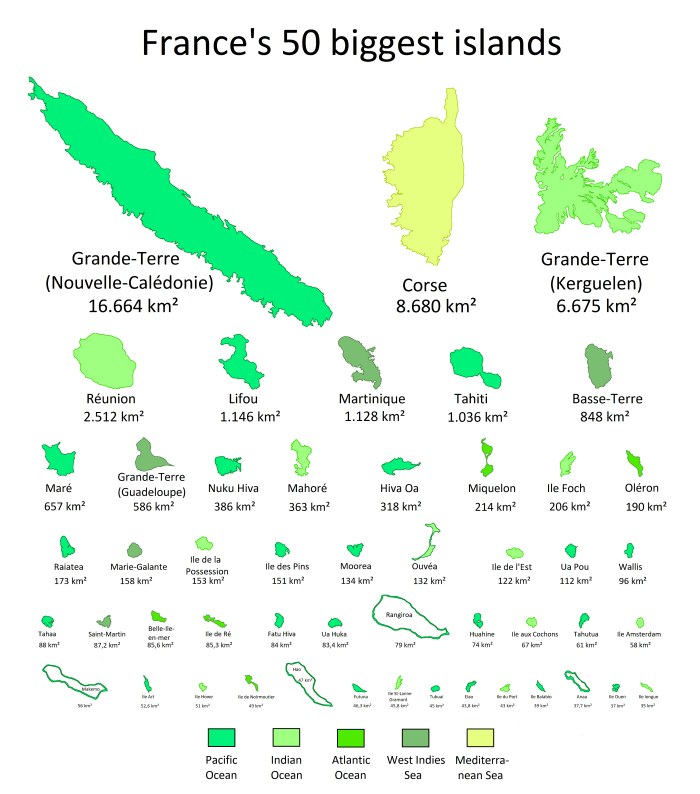

Eye Candy: France’s 50 largest islands

This is pretty cool. France still has an overseas presence in the Pacific, the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, the Indian and Antarctic oceans, and the Atlantic (including St. Pierre and Miquelon, an archipelago just off the coast of Newfoundland, a province of Canada). Here’s a good Wikipedia list of France’s islands. It’s in French. Translate it to English, if you must. Browse and soak it all in. Here is Jacques at NOL on all things French. And here is Vincent at NOL on all things Quebec, which is a French-speaking province in Canada.

Nightcap

- A new history of Islamic Spain Peter Gordon, Asian Review of Books

- A Palestinian perspective on Labour’s anti-Semitism row Nimer Sultany, Disorder of Things

- The crumbling of French culture Guillaume de Thieulloy, Law & Liberty

- Can Asia and Europe make America’s alliances great again? Tongfi Kim, the Diplomat

The Real Cost of National Health Care

Around early August 2018, a research paper from the Mercatus Center at George Mason University by Charles Blahous made both the Wall Street Journal and Fox News within two days. It also attracted attention widely in other media. Later, I thought I heard sighs of satisfaction from conservative callers on talk show radio whenever the paper came up.

One figure from the study came and stayed at the surface and was quoted correctly many times (rare occurrence) in the electronic media. The cost of what Senator Sanders proposed with respect to national health care was:

30 trillion US dollars over ten years (actually, 32.6 over thirteen years).

This enormous number elicited pleasure among conservatives because it seemed to underscore the folly of Senator Bernie Sanders’ call for universal healthcare. It meant implicitly, federal, single-payer, government-organized health care. It might be achieved simply by enrolling everyone in Medicare. I thought I could hear snickers of relief among my conservative friends because of the seeming absurdity of the gigantic figure. I believe that’s premature. Large numbers aren’t always all they appear to be.

Let’s divide equally the total estimate over ten years. That’s three trillion dollars per year. It’s also a little more than $10,000 per American man, woman, child, and others, etc.

For the first year of the plan, Sanders’ universal health care amounts to 17.5% of GDP per capita. GDP per capita is a poor but not so bad, really, measure of production. It’s also used to express average gross income. (I think that those who criticize this use of GDP per capita don’t have a substitute to propose that normal human beings understand, or wish to understand.) So it’s 17.5% of GDP/capita. The person who is exactly in the middle of the distribution of American income would have to spend 17.5% of her income on health care, income before taxes and such. That’s a lot of money.

Or, is it?

Let’s imagine economic growth (GDP growth) of 3% per years. It’s optimistic but it’s what conservatives like me think is a realistic target for sustained performance. From 1950 to 1990, GDP per capita growth reached or exceeded 3% for almost all years. It greatly exceeded 3% for several years. I am too lazy to do the arithmetic but I would be bet that the mean annual GDP growth for that forty-year period was well above 3%. So, it’s realistic and probably even modest.

At this 3% growth rate, in the tenth year, the US GDP per capita will be $76.600. At that point, federal universal health care will cost – unless it improves and thus becomes more costly – 13% of GDP per capita. This sounds downright reasonable, especially in view of the rapid aging of the American population.

Now, American conservative enemies of nationalized health care are quick to find instances of dysfunctions of such healthcare delivery systems in other countries. The UK system was the original example and as such, it accumulated mistakes. More recently, we have delighted in Canadian citizens crossing the border for an urgent heart operation their nationalized system could not produce for months: Arrive on Friday evening in a pleasant American resort. Have a good but reasonable dinner. Check in Sat morning. Get the new valve on Monday; back to Canada on Wednesday. At work on the next Monday morning!

The subtext is that many Canadians die because of a shortage of that great free health care: It nice if you can get it, we think. Of course, ragging on the Canadians is both fair and endlessly pleasant. Their unfailing smugness in such matters is like a hunting permit for mental cruelty!

In fact, though, my fellow conservatives don’t seem to make much of an effort to find national health systems that actually work. Sweden has one, Denmark has one; I think Finland has one; I suspect Germany has one. Closer to home, for me, at least, France has one. Now, those who read my blogging know that I am not especially pro-French or pro-France. But I can testify to a fair extent that the French National Healthcare works well. I have used it several times across the past fifty years. I have observed it closely on the occasion of my mother’s slow death.

The French national health system is friendly, almost leisurely, and prompt in giving you appointments including to specialists. It tends to be very thorough to the point of excessive generosity, perhaps. Yes, but you get what you pay for, I can hear you thinking – just like a chronically pessimistic liberal would. Well, actually, Frenchmen live at least three years longer on the average than do American men. And French women live even longer. (About the same as Canadians, incidentally.)

Now, the underlying reasoning is a bit tricky here. I am not stating that French people live longer than Americans because the French national healthcare delivery system is so superior. I am telling you that whatever may be wrong with the French system that escaped my attention is not so bad that it prevents the French from enjoying superior longevity. I don’t want to get here into esoteric considerations of the French lifestyle. And, no, I don’t believe it’s the red wine. The link between drinking red wine daily and cardiac good health is in the same category as Sasquatch: I dearly hope it exists but I am pretty sure it does not. So, I just wish to let you know that I am not crediting French health care out of turn.

The weak side of the French system is that it remunerates doctors rather poorly, from what I hear. I doubt French pediatricians earn $222,000 on the average. (Figure for American pediatricians according to the Wall Street Journal 8/17/18.) But I believe in market processes. France the country has zero trouble finding qualified candidates for its medical schools. (I sure hope none of my current doctors, whom I like without exception, will read this. The wrong pill can so easily happen!)

By the way, I almost forgot to tell you. Total French health care expenditure per person is only about half as high as the American. Rule of thumb: Everything is cheaper in the US than in other developed countries, except health care.

And then, closer to home, there is a government health program that covers (incompletely) about 55 million Americans. It’s not really “universal” even for the age group it targets because one must have contributed to benefit. (Same in France, by the way, at least in principle.) It’s universal in the sense that everyone over 65 who has contributed qualifies. It’s not a charity endeavor. Medicare often slips the minds of critical American conservatives, I suspect, I am guessing, because there are few complaints about it.

That’s unlike the case for another federal health program, for example the Veterans’, which is scandal-ridden and badly run. It’s also unlike Medicaid, which has the reputation of being rife with financial abuse. It’s unlike the federally run Indian Health Service that is on the verge of being closed for systemic incompetence.

I suspect Medicare works well because of a large number of watchful beneficiaries who belong to the age group in which people vote a great deal. My wife and I are both on Medicare. We wish it would cover us 100%, although we are both conservatives, of course! Other than that, we have no complaints at all.

Sorry for the seeming betrayal, fellow conservatives! Is this a call for universal federal health care in America? It’s not, for two reasons. First, every country with a good national health system also has an excellent national civil service, France, in particular. I have no confidence, less than ever in 2018, that the US can achieve the level of civil service quality required. (Less in 2018 because of impressive evidence of corruption in the FBI and in the Justice Department, after the Internal Revenue Service).

Secondly, when small government conservatives (a redundancy, I know) attempt to promote their ideas for good government primarily on the basis of practical considerations, they almost always fail. Ours is a political and a moral posture. We must first present our preferences accordingly rather than appeal to practicality. We should not adopt a system of health delivery that will, in ten years, attribute the management of 13% of our national income to the federal government because it’s not infinitely trustworthy. We cannot encourage the creation of a huge category of new federal serfs (especially of well-paid serfs) who are likely forever to constitute a pro-government party. We cannot, however indirectly, give the government most removed from us, a right of life and death without due process.

That simple. Arguing this position looks like heavy lifting, I know, but look at the alternative.

PS I like George Mason University, a high ranking institution of higher learning that gives a rare home to conservative American scholars, and I like its Mercatus Center that keeps producing high-level research that is also practical.

Nightcap

- Fear of a Black France Grégory Pierrot, Africa is a Country

- Children of the Rohingyas and their Search for Identity Iffat Nawaz, Coldnoon

- The Invention of Representative Democracy Katlyn Marie Carter, Age of Revolutions

- Is psychedelics research closer to theology than science? Jules Evans, Aeon

Ottomanism, Nationalism, Republicanism II

In the last post, I gave some historical background on how the Ottoman state, whether in reformist or repressive mode (or some combination of the two), was on a road, at least from the early nineteenth century, that was very likely to end in a nation-state for the Turks of Anatolia and the Balkan region of Thrace, which forms a hinterland in its eastern part for the part of Istanbul on the Balkan side of the Bosphorus. Despite the centuries of the Ottoman dynasty (the founder Othman was born in 1299 and this is usually taken as the starting point of the Ottoman state, though obviously there was no such thing when Othman was born), it was also an increasing possibility that the nation-state would be a republic on the French model.

The obvious alternative being a style of monarchism mixing populism and (rather constructed) tradition, born out of a national movement and accommodating the idea of a popular will represented by the monarch, mixed in varying degrees with constitutional and representative institutions. The clearest example of this style is maybe Serbia, to which can be added Montenegro, Bulgaria, Romania and Greece. The older monarchies of imperial Germany and Russia incorporated elements of populist-national monarchy. The Austro-Hungarian Empire, as the Habsburg empire based in Vienna for many centuries became known in 1867, was the Empire most lacking in a core and not surprisingly suffered the most complete disintegration after World War One (that great killer of Empires).

France was the exception in Europe as a republic, particularly as a unitary republic, and was only continuously a republic from 1870. In 1870, Switzerland was the only other republic, but known as the Swiss Confederation, with strong powers for the constituent cantons. The example of French republicanism was still supremely important because of the transformative nature of the 1789 French Revolution, and the ways its development became central events in European history. Part of that came out of the preceding status of France as the premier European nation and the biggest cultural force of the continent. Educated Ottomans were readers of French, and Ottoman political exiles were often in Paris.

High level education often meant studying in Paris. This had such a big influence on the fine arts, including architecture, that apparently 19th century architecture in Istanbul was more based on French Orientalism than earlier Ottoman architecture. The religious conservatives and neo-Ottomanists in power today, who claim to represent authenticity and escape from western models, in reality promote imitation of these 19th century imports.

Ottoman intellectuals and writers read French and were familiar with the idea of France as intellectual and political leader. There were other influences, including important relations with Imperial Germany, but French influence had a particular status for those aiming for change.

Namık Kemal, the ‘Young Ottoman’ reformer who has some continuing appeal to the moderate political right in Turkey, as demonstrated in the foundation of a Namık Kemal University in Thrace 4 years after the AKP came to power, appearing more moderate conservvative than it does now, translated Montesquieu’s The Spirit of the Laws into Ottoman Turkish (modern Turkish is based on major changes from Ottoman).

The more radical reformers who came to power in 1908 were known as Young Turks, that is Jeunes Turcs, often now written in half-Turkish, half-French style as Jön Türkler. The more radical reformers wanted less role for Islam in public life and at the most radical end even regarded Islam as responsible for backwardness. French laicism was therefore a natural pole of attraction, as were the ways nationalism and republicanism came together in the French revolutionary legacy as an expression of the sovereignty of the people.

The Ottomans studying in France were strong influenced by the sociology of Emile Durkheim, who is usually counted as one of the three founders of the discipline of sociology, along with Karl Marx and Max Weber. Durkheim’s social thought was very influenced by an understanding of Montesquieu and Jean-Jacques Rousseau as precursors of sociology. This partly reflects the social analysis they engaged in, but also their idea of how a society is constituted legally and politically, particularly Rousseau’s theory of the social contract. Durkheim’s social thought is permeated by concerns with what kind of social solidarity there can be in modern societies in ways which build on the long history of republican thinking about a community of citizens. This was very important in the late Ottoman and early republican period.

The German

Max Weber was also a major influence. His ideas about disenchantment (a version of secularisation) and the role of the nation-state were of definite interest to Turkish thinkers inclined towards republicanism, nationalism, and secularism. One of the consequences of this is that criticisms of the Turkish republican tradition, as it passed through Kemal Atatürk (‘Kemalism’), are tied up with criticisms of Weber. Some of this Turkish absorption of Durkheim and Weber can be found in English in the work of Ziya Gökalp (1876-1924) and Niyazi Berkes (1908-1988).

It is also worth finding Atatürk’s Great Speech of 1927 (a book length text read out over several days), which is a political intervention not a discussion of social theory, but does show how ideas connected with social theory enter political discourse in Turkey. It is very widely distributed in Turkey, I’ve even seen it on sale in Turkish supermarkets; and it has been translated into English. Berkes is the social scientist and has a rather more academic way of writing than Gökalp (a famously ambiguous thinker) or Atatürk. His The Development of Secularism in Turkey (published in English 1964, while he was working at McGill University in Montreal) must be the single most influential work of social science by a Turk or about Turkey.

Unfortunately a discussion of republicanism in relation to Durkheim, Weber, or any other major thinkers declined after the 1920s and Berkes is really the last great flowering of this tradition in Turkey. This is part of the story of how Turkish republicanism as a mode of thinking declined into defensive gestures and the repetition of dogmas, so is also the history of how extremely superficial gestures towards liberalism by leaders of the Turkish right had undue influence over the more liberal parts of Turkish thinking.

The weakness of thought about republicanism and the superficial absorption of liberalism was the main thread on the intellectual side leading to the disaster of Erdoğan-AKP rule. The rise of AKP was welcomed by many (I suspect most, but I don’t know any ways in which this has been quantified) Turkish liberals until the suppression of the Gezi movement in 2013 and even in some cases until the wave of repression following the coup attempt of 2016.

To be continued

From Petty Crime to Terrorism

I grew up in France. I know the French language inside out. I follow the French media. In that country, France, people with a Muslim first name are 5% or maybe, 7% of the population. No one estimates that they are close to 10%. I use this name designation because French government agencies are forbidden to cooperate in the collection of religious (or ethic, or racial) data. Moreover, I don’t want to be in the theological business of deciding who is a “real Muslim.” Yet, common sense leads me to suspect that French people who are born Muslims are mostly religiously indifferent or lukewarm, like their nominally Christian neighbors. I am not so sure though about recent immigrants from rural areas bathed in a jihadist atmosphere, as occur in Algeria, and in Morocco, for example. Continue reading

On demography and living standards in the colonial era

This is a topic that has been bugging me. Very often, historians will (accurately) point out mortality statistics in the United States, Canada (Quebec) and the Latin America during the colonial era were better than in the comparable Old World (comparing French with French, British with British, Spanish with Spanish). However, they will argue that this is evidence that living standards were higher. This is where I wish to make an important nuance.

Settlement colonies (so, here there is a bigger focus on North America, but it applies to smaller extent to Latin America which I am more tempt to label as extractive – see here) are generally frontier economies. This means that they are small economies because of small populations. This means that labor and capital are scarce relative to land. All outputs that come from the relatively abundant factor will thus tend to be cheaper if there is little international trade for the goods that they are best at producing. The colonial period pretty much fits that bill. The American and Canadian colonies were basically agricultural colonies, but very few of those agricultural outputs actually crossed the Atlantic. As such, agricultural produces were cheap. This is akin to saying that nutrition was cheap.

This, by definition, will give settlement colonies an advantage in terms of biological living standards. As they are not international price takers, wheat is cheaper than in the old world. This is why James Lemon spoke of the New World as the “Best poor man’s country” (I love that expression) : it was easy to earn subsistence. However, beyond that it is very hard to go beyond. For example, in my dissertation (articles still in consideration at Cliometrica and Canadian Journal of Economics) I found that when wages were deflated by a subsistence basket containing very few services and manufactured goods and which relied heavily on untransformed foods, Canada was richer than the richest city of France. Once you shifted to a basket that marginally increased transformed goods and manufactured goods, the advantage was wiped away.

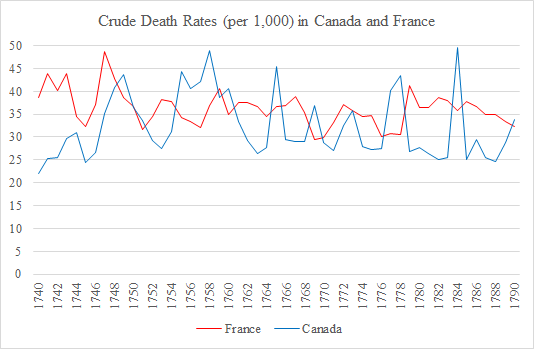

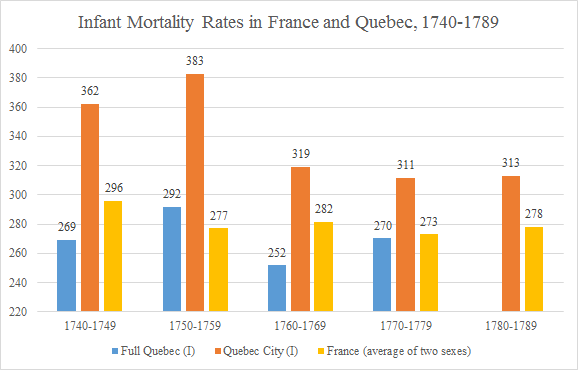

Yet, everything indicates that mortality rates were greater in Paris and France and than in Quebec City and Quebec as a whole (but not by a lot) (see images below). Similar gaps seem to exist for the United States relative to Britain, but the data is not as rich as for Quebec. However, the data that exists for New England suggests that death rates were lower than in England but the “bare bones” real incomes measured by Lindert and Williamson show that New England may have been poorer than Great Britain (not by much though).

I am not saying that demographic and biological data is worthless. Quite the contrary (even I wanted to, I could not since I have a paper on the heights of French-Canadians from 1780 to 1830)! The point is that data matters in context. The world is full of small non-linearities between variables. While “good” demographic outcomes are generally tracking “good” economic outcomes, there are contexts where this may be a weaker relation (curvilinear relations between variables). I think that this is a good example of that point.

How poor was 18th century France? Steps towards testing the High-Wage Hypothesis (HWE)

A few days ago, one of my articles came online at the Journal of Interdisciplinary History. It is a research note, but as far as notes go this one is (I think) an important step forwards with regards to the High-Wage Hypothesis (henceforth HWE for high-wage economy) of industrialization.

In the past, I explained my outlook on this theory which proposes that high wages relative to energy was a key driver of industrialization. As wages were high while energy was cheap, firms had incentives to innovate and develop labor-saving technologies. I argued that I was not convinced by the proposition because there were missing elements to properly test its validity. In that post I argued that to answer why the industrial revolution was British we had to ask why it was not French (a likely competitor). For the HWE to be a valid proposition, wages had to be higher in England than in France by a substantial margin. This is why I have been interested in living standards in France.

In his work, Robert Allen showed that Paris was the richest city in France (something confirmed by Phil Hoffman in his own work). It was also poorer than London (and other British cities). The other cities of France were far behind. In fact, by the 18th century, Allen’s work suggests that Strasbourg (the other city for which he had data) was one of the poorest in Europe.

In the process of assembling comparisons between Canada and France during the colonial era (from the late 17th to the mid-18th centuries), I went to the original sources that Allen used and found that the level of living standards is understated. First, I found out that the wages were not for Strasbourg per se. They applied to a semi-rural community roughly 70km away from Strasbourg. Urban wages and rural wages tend to differ massively and so they were bound to show lower living standards. Moreover, the prices Allen used for his basket applied to urban settings. This means that the wages used were not comparable to the other cities used. I also found out that the type of work that was reported in the sources may not have belonged to unskilled workers but rather to semi-skilled or even skilled workers and that the wages probably included substantial in-kind payments.

Unfortunately, I could not find a direct solution to correct the series proposed by Allen. However, there were two ways to circumvent the issue. The most convincing of those two methods relies on using the reported wages for agricultural workers. While this breaks with the convention established by Allen (a justifiable convention in my opinion) of using urban wages and prices, it is not a problem if we compare with similar types of wage work. We do have similar data to compare with in the form of Gregory Clark’s farm wages in England. The wage rates computed by Allen placed Strasbourg at 64% of the level of wages for agricultural workers in England between 1702 and 1775. In comparison, the lowest of the agricultural wage rates for the Alsatian region places the ratio at 74%. The other wage rates are much closer to wages in England. The less convincing methods relies on semi-skilled construction workers – which is not ideal. However, when these are compared to English wages, they are also substantially higher.

Overall, my research note attempts a modest contribution: properly measure the extent to which wages were lower in France than in Britain. I am not trying to solve the HWE debate with this. However, it does come one step closer to providing the information to do so. Now that we know that the rest of France was not as poor as believed (something which is confirmed by the recent works of Leonardo Ridolfi and Judy Stephenson), we can more readily assess if the gap was “big enough” to matter. If it was not big enough to matter, then we have to move to one of the other five channels that could confirm the HWE (at least that means I have more papers to write).

The best economic history papers of 2017

As we are now solidly into 2018, I thought that it would be a good idea to underline the best articles in economic history that I read in 2017. Obviously, the “best” is subjective to my preferences. Nevertheless, it is a worthy exercise in order to expose some important pieces of research to a wider audience. I limited myself to five articles (I will do my top three books in a few weeks). However, if there is an interest in the present post I will publish a follow-up with another five articles.

O’Grady, Trevor, and Claudio Tagliapietra. “Biological welfare and the commons: A natural experiment in the Alps, 1765–1845.” Economics & Human Biology 27 (2017): 137-153.

This one is by far my favorite article of 2017. I stumbled upon it quite by accident. Had this article been published six or eight months earlier, I would never have been able to fully appreciate its contribution. Basically, the authors use the shocks induced by the wars of the late 18th century and early 19th century to study a shift from “self-governance” to “centralized governance” of common pool resources. When they speak of “commons” problems, they really mean “commons” as the communities they study were largely pastoral communities with area in commons. Using a difference-in-difference where the treatment is when a region became “centrally governed” (i.e. when organic local institutions were swept aside), they test the impact of these top-down changes to institutions on biological welfare (as proxied by infant mortality rates). They find that these replacements worsened outcomes.

Now, this paper is fascinating for two reasons. First, the authors offer a clear exposition of its methodology and approach. They give just the perfect amount of institutional details to assuage doubts. Second, this is a strong illustration of the points made by Elinor Ostrom and Vernon Smith. These two economists emphasize different aspects of the same thing. Smith highlights that “rationality” is “ecological” in the sense that it is an iterative process of information discovery to improve outcomes. This includes the generation of “rules of the game” which are meant to sustain exchanges. These rules need not be formal edifices. They can be norms, customs, mores and habits (generally supported by the discipline of continuous dealings and/or investments in social-distance mechanisms). On her part, Ostrom emphasized that the tragedy of the commons can be resolved through multiple mechanisms (what she calls polycentric governance) in ways that do not necessarily require a centralized approach (or even market-based approaches).

In the logic of these two authors, attempts at “imposing” a more “rational” order (from the perspective of the planner of this order) may backfire. This is why Smith often emphasizes the organic nature of things like property rights. It also shows that behind seemingly “dumb” peasants, there is often the weight of long periods of experimentation in order to adapt rules and norms in order to fit the constraints faced by the community. In this article, we can see those two things – the backfiring and, by logical implication, the strengths of the organic institutions that were swept away.

Fielding, David, and Shef Rogers. “Monopoly power in the eighteenth-century British book trade.” European Review of Economic History 21, no. 4 (2017): 393-413.

In this article, the authors use a legal change caused by the end of the legal privileges of the Stationers’ Company (which amounted to an easing of copyright laws). The market for books may appear to be “non-interesting” for mainstream economics. However, this would be a dramatic error. The “abundance” of books is really a recent development. Bear in mind that the most erudite monk of the late middle ages had less than fifty books from which to draw knowledge (this fact is a vague recollection of mine from Kenneth Clark’s art history documentary from the late 1960s which was aired by the BBC). Thus, the emergence of a wide market for books – which is dated within the period studied by the authors of this article – should not be ignored. It should be considered as one of the most important development in western history. This is best put by the authors when they say that “the reform of copyright law has been regarded as one of the driving forces behind the rise in book production during the Enlightenment, and therefore a key factor in the dissemination of the innovations that underpinned Britain’s Industrial Revolution”.

However, while they agree that the rising popularity of books in the 18th century is an important historical event, they contest the idea that liberalization had any effect. They find that the opening up of the market to competition had little effects on prices and book production. They also find that mark-ups fell but that this could not be attributed to liberalization. At first, I found these results surprising.

However, when I took the time to think about it I realized that there was no reason to be surprised. First, many changes have been heralded as crucial moments in history. More often than not, the importance of these changes has been overstated. A good example of an overstated change has been the abolition of the Corn Laws in England in the 1840s. The reduction in tariffs, it is argued, ushered Britain into an age of free trade and falling food prices.

In reality, as John Nye discusses, protectionist barriers did not fall as fast as many argued and there were reductions prior to the 1846 reform as Deirdre McCloskey pointed out. It also seems that the Corn Laws did not have substantial effects on consumption or the economy as a whole (see here and here). While their abolition probably helped increase living standards, it seems that the significance of the moment is overstated. The same thing is probably at play with the book market.

The changes discussed by Fielding and Rogers did not address the underlying roots of the level of market power enjoyed by industry players. In other words, it could be that the reform was too modest to have an effect. This is suggested by the work of Petra Moser. The reform studied by Fielding and and Rogers appears to have been short-lived as evidenced by changes to copyright laws in the early 19th century (see here and here). Moser’s results point to effects much larger (and positive for consumers) than those of Fielding and Rogers. Given the importance of the book market to stories of innovation in the industrial revolution, I really hope that this sparks a debate between Moser and Fielding and Rogers.

Johnson, Noel D., and Mark Koyama. “States and economic growth: Capacity and constraints.” Explorations in Economic History 64 (2017): 1-20.

I am biased as I am fond of most of the work of these two authors. Nevertheless, I think that their contribution to the state capacity debate is a much needed one. I am very skeptical of the theoretical value of the concept of state capacity. The question always lurking in my mind is the “capacity to do what?”.

A ruler who can develop and use a bureaucracy to provide the services of a “productive state” (as James Buchanan would put it) is also capable of acting like a predator. I actually emphasize this point in my work (revise and resubmit at Health Policy & Planning) on Cuban healthcare: the Cuban government has the capacity to allocate large quantities of resources to healthcare in amounts well above what is observed for other countries in the same income range. Why? Largely because they use health care for a) international reputation and b) actually supervising the local population. As such, members of the regime are able to sustain their role even if the high level of “capacity” comes at the expense of living standards in dimensions other than health (e.g. low incomes). Capacity is not the issue, its capacity interacting with constraints that is interesting.

And that is exactly what Koyama and Johnson say (not in the same words). They summarize a wide body of literature in a cogent manner that clarifies the concept of state capacity and its limitations. In doing so, they ended up proposing that the “deep roots” question that should interest economic historians is how “constraints” came to be efficient at generating “strong but limited” states.

In that regard, the one thing that surprised me from their article was the absence of Elinor Ostrom’s work. When I read about “polycentric governance” (Ostrom’s core concept), I imagine the overlap of different institutional structures that reinforce each other (note: these structures need not be formal ones). They are governance providers. If these “governance providers” have residual claimants (i.e. people with skin in the game), they have incentives to provide governance in ways that increased the returns to the realms they governed. Attempts to supersede these institutions (e.g. like the erection of a modern nation state) requires dealing with these providers. They are the main demanders of constraints which are necessary to protect their assets (what my friend Alex Salter calls “rights to the realm“). As Europe pre-1500 was a mosaic of such governance providers, there would have been great forces pushing for constraints (i.e. bargaining over constraints).

I think that this is where the literature on state capacity should orient itself. It is in that direction that it is the most likely to bear fruits. In fact, there have been some steps taken in that direction For example, my colleagues Andrew Young and Alex Salter have applied this “polycentric” narrative to explain the emergence of “strong but limited states” by focusing on late medieval institutions (see here and here). Their approach seems promising. Yet, the work of Koyama and Johnson have actually created the room for such contributions by efficiently summarizing a complex (and sometimes contradictory) literature.

Bodenhorn, Howard, Timothy W. Guinnane, and Thomas A. Mroz. “Sample-selection biases and the industrialization puzzle.” The Journal of Economic History 77, no. 1 (2017): 171-207.

Elsewhere, I have peripherally engaged discussants in the “antebellum puzzle” (see my article here in Economics & Human Biology on the heights of French-Canadians born between 1780 and 1830). The antebellum puzzle refers to the possibility that the biological standard of living (e.g. falling heights, worsening nutrition, increased mortality risks) fell while the material standard of living increased (e.g. higher wages, higher incomes, access to more services, access to a wider array of goods) during the decades leading to the American Civil War.

I am inclined to accept the idea of short-term paradoxes in living standards. The early 19th century witnessed a reversal in rural-urban concentration in the United States. The country had been “deurbanizing” since the colonial era (i.e. cities represented an increasingly smaller share of the population). As such, the reversal implied a shock in cities whose institutions were geared to deal with slowly increasing populations.

The influx of people in cities created problems of public health while the higher level of population density favored the propagation of infectious diseases at a time where our understanding of germ theory was nill. One good example of the problems posed by this rapid change has been provided by Gergely Baics in his work on the public markets of New York and their regulation (see his book here – a must read). In that situation, I am not surprised that there was a deterioration in the biological standard of living. What I see is that people chose to trade-off shorter wealthier lives against longer poorer lives. A pretty legitimate (albeit depressing) choice if you ask me.

However, Bodenhorn et al. (2017) will have none of it. In a convincing article that has shaken my priors, they argue that there is a selection bias in the heights data – the main measurement used in the antebellum puzzle debate. Most of the data on heights comes either from prisoners or enrolled volunteer soldiers (note: conscripts would not generate the problem they describe). The argument they make is that as incomes grow, the opportunity cost of committing a crime or of joining the army grows. This creates the selection bias whereby the sample is going to be increasingly composed of those with the lowest opportunity costs. In other words, we are speaking of the poorest in society who also tended to be shorter. Simultaneously, fewer tall individuals (i.e. rich individuals) committed crimes or joined the army because incomes grew. This logic is simple and elegant. In fact, this is the kind of data problem that every economist should care about when they design their tests.

Once they control for this problem (through a meta-analysis), the puzzle disappears. I am not convinced by the latter part of the claim. Nevertheless, it is very likely that the puzzle is much smaller than initially gleaned. In yet to be published work, Ariell Zimran (see here and here) argues that the antebellum puzzle is robust to the problem of selection bias but that it is indeed diminished. This concedes a large share of the argument to Bodenhorn et al. While there is much to resolve, this article should be read as it constitutes one of the most serious contributions to the field of economic history published in 2017.

Ridolfi, Leonardo. “The French economy in the longue durée: a study on real wages, working days and economic performance from Louis IX to the Revolution (1250–1789).” European Review of Economic History 21, no. 4 (2017): 437-438.

I discussed Leonardo’s work elsewhere on this blog before. However, I must do it again. The article mentioned here is the dissertation summary that resulted from Leonardo being a finalist to the best dissertation award granted by the EHES (full dissertation here). As such, it is not exactly the “best article” published in 2017. Nevertheless, it makes the list because of the possibilities that Leonardo’s work have unlocked.

When we discuss the origins of the British Industrial Revolution, the implicit question lurking not far away is “Why Did It Not Happen in France?”. The problem with that question is that the data available for France (see notably my forthcoming work in the Journal of Interdisciplinary History) is in no way comparable with what exists for Britain (which does not mean that the British data is of great quality as Judy Stephenson and Jane Humphries would point out). Most estimates of the French economy pre-1790 were either conjectural or required a wide array of theoretical considerations to arrive at a deductive portrait of the situation (see notably the excellent work of Phil Hoffman). As such, comparisons in order to tease out improvements to our understanding of the industrial revolution are hard to accomplish.

For me, the absence of rich data for France was particularly infuriating. One of my main argument is that the key to explaining divergence within the Americas (from the colonial period onwards) resides not in the British or Spanish Empires but in the variation that the French Empire and its colonies provide. After all, the French colony of Quebec had a lot in common geographically with New England but the institutional differences were nearly as wide as those between New England and the Spanish colonies in Latin America. As such, as I spent years assembling data for Canada to document living standards in order to eventually lay down the grounds to test the role of institutions, I was infuriated that I could do so little to compare with France. Little did I know that while I was doing my own work, Leonardo was plugging this massive hole in our knowledge.

Leonardo shows that while living standards in France increased from 1550 onward, the level was far below the ones found in other European countries. He also showed that real wages stagnated in France which means that the only reason behind increased incomes was a longer work year. This work has also unlocked numerous other possibilities. For example, it will be possible to extend to France the work of Nicolini and Crafts and Mills regarding the existence of Malthusian pressures. This is probably one of the greatest contribution of the decade to the field of economic history because it simply went through the dirty work of assembling data to plug what I think is the biggest hole in the field of economic history.

BC’s weekend reads

- “What equivalent claims (if they could be established) would falsify your political position?“

- “White males may enjoy a great deal of privilege, but they still have rights, and when those rights are violated, they ought to be rectified.“

- “[…] actually, the whole country of France is like an attractive museum that would have a superlative cafeteria attached.“

- “They worked hard to look like they weren’t working too hard.“

BC’s weekend reads

- heads roll at top of Turkey’s military in latest purge | Turkey’s 16th of April referendum will pave the way for authoritarianism

- great piece on Macron’s recent economic policies | French expatriates and foreign Francophiles

- Italy will be the EU’s third power once the UK leaves | the uniqueness of Italian internal divergence

- attempts to shut down free speech will no longer be tolerated, at least at Claremont McKenna | when is speech violence?

- cool science stuff is gonna happen soon | what makes it science?

Algeria: a sparse memory

In 1962, France and the Algerian nationalists came to an agreement about Algerian independence. That was after 130 years of French colonization and eight years of brutal war including war against civilians. I participated in the evacuation of large number of French civilians from the country as a little sailor. The number who wanted to leave was much greater than anyone expected. It was too bad that they left in such large numbers. It was a pity for all concerned. The events were a double tragedy or a tragedy leading to a tragedy. The Algerian independence fighters who had prevailed by shedding quantities of their blood were not (not) Islamists. In most respects, intellectually and otherwise, they were a lot like me.

The true revolutionaries were soon replaced however by professional soldiers that I think of as classical but fairly moderate fascists. I went back to Algeria six years after independence. I was warmly received and I liked the people there. People invited me to lunch; I shared with them the fish I caught and a baby camel tried to browse my hair in a cafe.

I still think the nationalists were on the right side of the argument but I miss Algeria nevertheless. It’s like a divorce that should not have happened. And I am very sorry about where French incompetence and rigidity led everyone, especially the Algerians who keep migrating to France in huge numbers because they can’t find what they need at home.

Adam Smith on the character of the American rebels

They are very weak who flatter themselves that, in the state to which things have come, our colonies will be easily conquered by force alone. The persons who now govern the resolutions of what they call their continental congress, feel in themselves at this moment a degree of importance which, perhaps, the greatest subjects in Europe scarce feel. From shopkeepers, tradesmen, and attornies, they are become statesmen and legislators, and are employed in contriving a new form of government for an extensive empire, which, they flatter themselves, will become, and which, indeed, seems very likely to become, one of the greatest and most formidable that ever was in the world. Five hundred different people, perhaps, who in different ways act immediately under the continental congress; and five hundred thousand, perhaps, who act under those five hundred, all feel in the same manner a proportionable rise in their own importance. Almost every individual of the governing party in America fills, at present in his own fancy, a station superior, not only to what he had ever filled before, but to what he had ever expected to fill; and unless some new object of ambition is presented either to him or to his leaders, if he has the ordinary spirit of a man, he will die in defence of that station.

Found here. Today, many people, especially libertarians in the US, celebrate an act of secession from an overbearing empire, but this isn’t really the case of what happened. The colonies wanted more representation in parliament, not independence. London wouldn’t listen. Adam Smith wrote on this, too, in the same book.

Smith and, frankly, the Americans rebels were all federalists as opposed to nationalists. The American rebels wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom because they were British subjects and they were culturally British. Even the non-British subjects of the American colonies felt a loyalty towards London that they did not have for their former homelands in Europe. Smith, for his part, argued that losing the colonies would be expensive but also, I am guessing, because his Scottish background showed him that being an equal part of a larger whole was beneficial for everyone involved. But London wouldn’t listen. As a result, war happened, and London lost a huge, valuable chunk of its realm to hardheadedness.

I am currently reading a book on post-war France. It’s by an American historian at New York University. It’s very good. Paris had a large overseas empire in Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Caribbean. France’s imperial subjects wanted to remain part of the empire, but they wanted equal representation in parliament. They wanted to send senators, representatives, and judges to Europe, and they wanted senators, representatives, and judges from Europe to govern in their territories. They wanted political equality – isonomia – to be the ideological underpinning of a new French republic. Alas, what the world got instead was “decolonization”: a nightmare of nationalism, ethnic cleansing, coups, autocracy, and poverty through protectionism. I’m still in the process of reading the book. It’s goal is to explain why this happened. I’ll keep you updated.

Small states, secession, and decentralization – three qualifications that layman libertarians (who are still much smarter than conservatives and “liberals”) argue are essential for peace and prosperity – are worthless without some major qualifications. Interconnectedness matters. Political representation matters. What’s more, interconnectedness and political representation in a larger body politic are often better for individual liberty than smallness, secession, and so-called decentralization. Equality matters, but not in the ways that we typically assume.

Here’s more on Adam Smith at NOL. Happy Fourth of July, from Texas.