On popular demand, I’m reviving a reoccurring theme of mine: teaching economic history through the lens of popular culture. Today: bonds, yields and 18th century English financial planning.

In what is probably my favourite piece ever written, I tried to estimate exactly how rich Mr. Darcy was – Mr. Darcy, of course, of Jane Austen’s classic novel Pride & Prejudice. I showed that whatever method you use to translate incomes to the present, all characters in Austen’s captivating story are astonishingly rich. But, as we well know today, there are large differences even among the superrich; compare Bernie Sanders (small-time millionaire) with George Lucas and Steven Spielberg (single-digit billionaires) or Jeff Bezos (wealthiest man alive).

Using Pride & Prejudice to illustrate some economic point is hardly unconventional (Piketty did this in his Capital in the Twenty-First Century), so let me similarly discuss 18th and 19th century British financial markets using the characters in this well-known tale.

The starting point is the following musing, courtesy of former Oxford Economist Martin Slater’s (2018: 52) The National Debt; how come “female characters in nineteenth-century novels always seem to have a suspiciously exact income of ‘so many pounds per year'”? Where does this money come from? Why is it so exact? And what’s the reason Piketty uses this particular literary example to illustrate the permanence and steady stream of income that capital somehow just throws off?

Consols and Financial Markets

Financial markets are truly awesome – not just in their impressive scope or potential devastation, but in the many different needs they simultaneously fulfil for many different people. Slater ably guides us through the confusing mishmash that is the 17th and 18th century English public finance, but what emerges by 1757, after Henry Pelham’s consolidation of government debt, is two main – and for our purposes, equivalent – securities: the Consolidated 3% Annuities (and the ‘Reduced annuities’), affectionately named ‘Consols’. These were permanent government bonds with annual interest payments of 3%. This means that they had no maturity date, i.e. the holder of the security could expect the government to keep paying 3% of the face value for all future (a Churchill-issued subsequent Consol was actually repaid and retired just a few years ago, after almost a century in service).

Two cool things happen. First, the “initial value” – the face value – of debt running in perpetuity becomes almost irrelevant, since all that matters for the issuer is the ability to maintain interest rate payments; there is no presumption of future repayment. Second, creditors – that is, holders of the Consols who receive the regular interest payments – may trade that asset on financial markets. Since the plethora of different debt assets were now condensed into a single, credible, identical and easily-identified asset, the market for 3% Consols in London developed into a very large and liquid market. With such ease of access and predictable and stable payoffs, the Consols became the instrument of saving for well-off families in Austen’s time.

A note on yields

The Consols, essentially a piece of paper with a face value of £100, entitled the owner to a perpetual stream of payments by the government, in this case 3% – or £3. Now, the actual price at which this paper could be sold in London fluctuated extensively depending on the conditions of the financial market and, most prominently in Austen’s lifetime, the Napoleonic wars. As the £3 annual pay was serviced by the British government, and financial strain during the war increased the risk for defaults (through a foreign invasion or British government itself), the price of Consols was chiefly reflecting the military success.

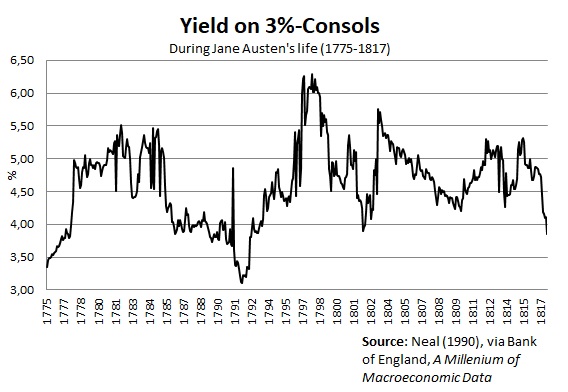

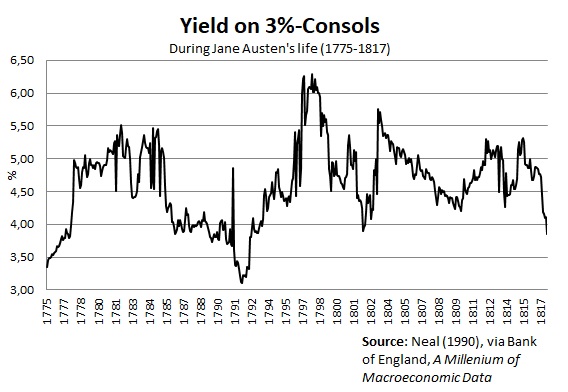

When the market price of a debt falls below its face value, the effective interest rate (the “yield”) that a prospective investor receives increases; paying £50 for a Consol with face value of £100 and a £3 perpetual interest payment, effectively earns the investor 6% interest instead of 3% (3/50 = 0.06). Since the Consols were the most dominant asset on the largest financial market in the world, their price became “the single most important asset price in the world economy” as Klovland (1994: 165) called it. Here’s the yield on Consols during Austen’s life:

It reached a low of 3.11% in 1792 (almost at par), and a high of 6.22% in 1798 (below £50) after the suspension of the gold standard.

The Bennets and the fortunes of handsome young men

The families of Pride & Prejudice made good use of this thriving financial market – not specifically for trading but for financial planning (others, such as British economist David Ricardo, and the banking families of Rothschild and Barings, made some of their fortune trading Consols).

In the novel, Mr. Bennet – the protagonist Lizzy’s father – has an income of £2,000 a year (again, see my 2016 piece for three different attempts at “translating” these sums into today’s money). It is not clear what his income comes from, but it’s a fair guess that it stems, like many other landed gentry of the time, from renting out farm lands belonging to the family home Longbourne. In addition, we know that Mrs. Bennet’s portion to the family home is a £5,000 contribution which is the sole inheritance the (five) Bennet daughters are entitled to.

Now, the way well-off families like the Bennets would make use of Consols was to ensure that non-inheriting children had at least some source of income after the passing of their father. The underlying concern in Pride & Prejudice, causing Mrs. Bennet to worry so about fortunate marriages for her daughters, is that the Bennet estate is entailed away to Mr. Collins – and with it the presumed rental income of £2,000 a year. That would leave the girls homeless, reduced to living off Mrs. Bennet’s inheritance of £5,000.

Austen began writing First Impressions (the initial title for Pride & Prejudice) in October 1796. During the decade leading up to this, the yield on Consols had been firmly within the interval 3.5-4.5%, hovering around 4% for years. It should thus not surprise us that Mrs. Bennet’s fortune of £5,000 presumably consisting of Consols, would have been purchased at around £75, predictably yielding the family an annual return of 4%. Indeed, the characters of Pride & Prejudice seem to be squarely set on 4% being the general norm. For instance, in a desperate attempt to enhance his already-inane proposal to Lizzy, Mr. Collins explicitly says:

“To fortune I am perfectly indifferent, and shall make no demand of that nature on your father, since I am well aware that it could not be complied with; and that one thousand pounds in the 4 per cents, which will not be yours till after your mother’s decease, is all that you may ever be entitled to.”

(Chapter 19, p. 133 in the 2009 HarperCollins edition)

Here we see the great use that Consols offered families like the Bennets. Once the Bennet parents pass away, the £5,000 of Consols could be divided equally among her children; Lizzy’s share would be a thousand pounds, which earns her an annual 4% interest return, or £40 (although maybe several year’s earnings for a regular worker, this was a rather small sum for such rich families – in contemplating Lizzy’s sister Lydia’s imprudent marriage, we learn that Mr. Bennet spent almost £100/year on Lydia’s purchases and pocket money alone). Being liquid financial assets, dividing up the Consols among children was very easy, and their steady income stream ensured that they would have at least some income. Bar Napoleonic conquest, the interest payment on the Consols would reliably show up year after year.

As for the handsome young men, Mr. Bingley’s case is easier than Mr. Darcy’s. We know that Bingley’s income is not agricultural, but investments from a fortune of almost £100,000 inherited from his father, who had not yet acquired an estate. The fortune was “acquired by trade”, where (being from the North) cotton or shipping are prime candidates, but the slave trade is also a possibility. We also know that the ambiguity of his annual income (£4,000 or £5,000) lies well within the return from a fortune of that size invested in Consols. Indeed, for Bingley to hold that kind of fortune, earn that income and still not have an estate of his own, suggests that his financial wealth consists predominantly of Consols – perhaps complemented with some other stock (Bank of England or East India Company stock are plausible candidates). Clearly, new money.

Mr. Darcy, on the other hand, is plainly old money. And a lot of it. There are subtle hints in the novel that Pemberley has been in the Darcy family for generations. What we don’t know is precisely how his £10,000 a year is earned. When visiting Pemberley in Derbyshire with her aunt and uncle, Lizzy is told by the housekeeper that Mr. Darcy is such a generous and fair man: “ask any of his tenants”, she says, which indicates that Mr. Darcy, has a fair number of them – as one would expect from a sizeable estate like Pemberley. Now, what we don’t know is if the entirety of his £10,000 a year is reaped from rental income; it could be that some of his income is financial – or that either his financial or rental income is excluded from this rumoured number. Beyond a mention of his sister, Georgiana’s, fortune of £30,000 – which for convenience would likely be held in Consols – we know very little about the personal finances of Mr. Darcy.

The use and abuse of Consols

The financial market for government debt in the late-18th and early 19th century was not created with financial planning in mind, but by incremental improvements to previous government funding problems. The outcome, however, was a striking success for Britain, whose thriving financial market in no small part accounted for Britannia’s Century until WWI.

Moreover, as contemporary economists from Ricardo and John Stuart Mill to Malthus and Lauderdale observed, the recurring interest payments, funded by taxes, may have had quite large macroeconomic consequences. Taxing ‘productive’ investments and trade in order to fund ‘unproductive’ holders of government debt was, it was argued, harmful to the country – and in a time where government expenditures largely consisted of the military and debt maintenance, the impacts of funding the debt was of prime political interest.

Piketty’s use of Austen’s England (and Balzac’s France) was used for precisely the same distinction. Wealth, in Piketty’s view, perpetuates itself, and effortlessly earns its return (never mind the work, risk and selection issues involved). By continually paying the interest on its debt, the governments of Austen’s Britain financed the leisurly lifestyles of the rich, just as the “natural” return of the modern-day rich contribute and maintain today’s inequality.

The Consol was a revolutionary invention, but it is possible that it was not part of Mr. Darcy’s Ten Thousand a Year.