- The art of everyday politics in imperial China Michael Szonyi, Aeon

- Busting the myth of Global Britain Nick Pearce, New Statesmen

- The Russia-Turkey-Iran Axis is flimsy, at best Dimitar Bechev, American Interest

- Does the West have a vision for the Western Balkans? Mieczysław Boduszyński, War on the Rocks

alliances

Bolton’s Iran policy: could it strengthen the China-Russia-Iran-Pakistan axis?

John Bolton, who took over as Donald Trump’s National Security Adviser on April 8, has had significant differences with India on a number of issues in the past. As US Ambassador to the UN, he opposed India’s elevation to the United National Security Council (UNSC), even at a time when relations were at a high during the Manmohan Singh-Bush era. Bolton had initially opposed the Indo-US nuclear deal, though later he lent his support. While the Trump administration has sought to elevate India’s role in the Indo-Pacific region, Bolton has expressed the view that there are some fundamental differences between India and the US. In the short term, though, there is no serious divergence.

Bolton and Iran

What would really be of concern to India however is Bolton’s hawkish approach towards Iran. Bolton’s views are not very different from those of US President Donald Trump and recently appointed Secretary of State John Pompeo. Bolton is opposed to the Iran Nuclear Agreement signed between Iran and P5+1 countries in 2015. In 2015, the NSA designate called for bombing Iran, last year he had criticized the deal, and last year he had called for scrapping the deal.

The Iranian response to Bolton’s appointment was understandably skeptical. Commenting on Bolton’s appointment, Hossein Naghavi Hosseini, the spokesman for the Iranian parliament’s National Security and Foreign Policy Commission, said: Continue reading

Recent developments in the context of Indo-Pacific

At a time when a massive churn is taking place in the Donald Trump Administration (HR Mcmaster was replaced as head of the NSA by John Bolton, while Secretary of State Rex Tillerson was replaced with the more hawkish Mike Pompeo), Alex Wong, Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs, gave a briefing with regard to the US vision for ‘Indo-Pacific’ strategy, on April 3, 2018 (a day before a trilateral dialogue took place between senior officials from India, Japan and US). Wong outlined the contours of the strategy, and spoke not just about the strategic vision, but also the economic vision of the US, with regard to the Indo-Pacific.

A backgrounder to the Indo-Pacific, Quad, and the China Factor

For a long time, the US referred to the region as ‘Asia-Pacific’ (which China prefers), but the current Trump Administration has been using the term ‘Indo-Pacific’. During his visit to East Asia and South East Asia, in November 2017, the US President had used the term more than once (much to the discomfort of China) giving a brief overview of what he meant by a ‘Free and Fair Indo-Pacific’. While speaking to a business delegation at Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation, Trump spoke about ‘rule of law’ and playing by the rules. Former Secretary of State Rex Tillerson had referred to the Indo-Pacific and the Quad Alliance (consisting of US, India, Japan, and Australia) in an address at the Center for Strategic and International Studies (a Washington think tank) in October 2017, a week before his India visit.

In order to give a further thrust to the Quad, representatives of all four countries met on the eve of East Asia Summit in Manila. A statement of the Indian Foreign Ministry said: Continue reading

Can Elizabeth Warren help turn the populist tide?

During her recent visit to China, a Democratic Senator from Massachusetts, Elizabeth Warren (perceived by many as a potential Presidential Candidate of the Democratic Party in 2020), came down heavily on US President Donald Trump’s approach towards foreign policy, arguing that it lacks substance, is unpredictable, and does not pay much attention to liberal values and human rights, which according to her has been the cornerstone of US foreign policy for a long time.

Trump’s unpredictability

Commenting on Trump’s unpredictable approach towards Asia, Warren stated:

This has been a chaotic foreign policy in the region, and that makes it hard to keep the allies that we need to accomplish our objectives closely stitched-in.

Critical of US approach towards China

Warren met with senior Chinese officials including Liu He, vice-premier for economic policy, Yang Jiechi, a top diplomat, and the minister of defense, Wei Fenghe, and discussed a number of important issues including trade and the North Korea issue.

Warren criticised China for being relatively closed, and stated that the US needed to have a more realistic approach towards Beijing. She also spoke of the need for the US to remain committed to raising Human Rights issues, and not skirt the issue, while dealing with China.

3 key problems with Trump’s style of functioning

The removal of Rex Tillerson as Secretary of State (who was replaced by Mike Pompeo, Director of the CIA) reiterates three key problems in US President Donald Trump’s style of functioning: First, his inability to get along with members of his team; second, impulsive decisions driven excessively by ‘optics’ and personal chemistry between leaders; and, finally, his inability to work in a system even where it is necessary.

Tillerson, who had differences with Trump on issues ranging from the Iran Nuclear Deal (which Trump has been wanting to scrap, though his stance was moderated by Tillerson) to the handling of North Korea, is not the first member (earlier senior individuals to be sacked are, amongst others, Michael Flynn, who was National Security Adviser, and Chief Strategist Steve Bannon) to exit hurriedly. Gary Cohn, Director of the National Economic Council, quit recently after opposing the US President’s tariffs on imports of steel and aluminium.

The US President tweeted this decision:

Mike Pompeo, Director of the CIA, will become our new Secretary of State. He will do a fantastic job! Thank you to Rex Tillerson for his service! Gina Haspel will become the new Director of the CIA, and the first woman so chosen. Congratulations to all!

The US President admitted that Tillerson’s style of functioning was very different from his own (alluding to the latter’s more nuanced approach on complex issues).

Interestingly, the US President did not even consult any of his staff members, including Tillerson, before agreeing to engage with North Korean Dictator Kim Jong Un. The South Korean National Security Advisor, Chung Eui Yong, had met with Trump and put forward the North Korean dictator’s proposal of a Summit.

The US President agreed to this proposal. Commenting on his decision to engage with Kim Jong Un, Trump tweeted:

Kim Jong Un talked about denuclearization with the South Korean Representatives, not just a freeze. Also, no missile testing by North Korea during this period of time. Great progress being made but sanctions will remain until an agreement is reached. Meeting being planned!

While Chung stated that the Summit would take place before May 2018, White House has not provided any specific dates.

There is absolutely no doubt that, at times, bold steps need to be taken to resolve complex issues like North Korea. Trump’s impulsive nature, however – refusing to go into the depth of things or seeking expert opinion – does not make for good diplomacy.

In fact, a number of politicians and journalist have expressed their skepticism with regard to where North Korean negotiations may ultimately lead. Ed Markey a Democratic Senator from Massachusetts, stated that Trump “must abandon his penchant for unscripted remarks and bombastic rhetoric to avoid derailing this significant opportunity for progress.”

In a column for the Washington Post, Jeffrey Lewis makes the point that there is a danger of Trump getting carried away by the attention he receives. Says Lewis in his column:

Some conservatives are worried that Trump will recognize North Korea as a nuclear-weapons state. They believe that an authoritarian North Korea will beguile Trump just as it did his erstwhile apprentice, American basketball player Dennis Rodman. They fear that Trump will be so overjoyed by the site of tens of thousands of North Koreans in a stadium holding placards that make up a picture of his face that he will, on the spot, simply recognize North Korea as a nuclear power with every right to its half of the Korean peninsula.

All Trump’s interlocutors have realized that while he is unpredictable, one thing which is consistent is the fact that he is prone to flattery. During his China visit, for instance, Trump was so taken aback by the welcome he received and the MOU’s signed with Chinese companies that he started criticizing his predecessors.

Finally, while Trump, like many global leaders, has risen as a consequence of being an outsider to the establishment, with people being disillusioned with the embedded establishment, the US President has still not realized that one of Washington’s biggest assets has been strategic alliances like NATO and multilateral trade agreements like NAFTA. The United States has also gained from globalization and strategic partnerships; it has not been one way traffic.

It remains to be seen how Tillerson’s removal will affect relations with key US allies. If Trump actually goes ahead with scrapping the Iran nuclear deal (2015), it will send a negative message not just to other members of the P5 grouping, but also India. In the last three years, India has sought to strengthen economic ties with Iran and has invested in the Chabahar Port Project. New Delhi is looking at Iran as a gateway to Afghanistan and Central Asia. If Tillerson’s successor just plays ball, and does not temper the US President’s style of conducting foreign policy, there is likely to be no stability and consistency and even allies would be skeptical.

Japan on its part would want its concerns regarding the abduction of Japanese citizens by Pyongyang’s agents, decades ago, to not get sidelined in negotiations with North Korea. (13 Japanese individuals were abducted in 2002, 5 have returned but the fate of the others remains unknown.) Prime Minister Shinzo Abe has made the return of the abductees a cornerstone of his foreign policy, and his low approval ratings due to a domestic scandal could use the boost that is usually associated with the plight of those abductees.

The removal of Tillerson underscores problems with Trump’s style of functioning as discussed earlier. The outside world has gotten used to the US President’s style of functioning and will closely be watching what Tillerson’s successor brings to the table.

Trump Is Right!

It is easy to emphasize all that is bad about the new American President. For sure, I think he is a clown who will do a few bad things to the US and the world at large. His protectionist agenda is of course a libertarian nightmare, which will also make the people who elected him worse off. Still, the US President is not a dictator, so some trust in the institutions and the actors that fill them still seems appropriate.

Trump is also plainly right on a number of issues. Foremost, his plea (also in yesterday’s inaugural address) for the partners of the USA, especially in NATO, to contribute in equal measure. This is not new, all recent American Presidents have pointed this out to their European allies. It is simply outrageous to let Mrs Jones from North Dakota pay for the defense of other rich countries, such as my home country of The Netherlands. The Europeans got away with major free riding. Only recently did they start to get their act a little bit together, as the Russian threat is looming again. The defense budgets in almost all European NATO members have decreased drastically since the early nineties, which is plainly immoral if you are in the world’s most important security organization together. So hopefully Trump will pressure them to the max.

He is also right in pointing out that many US foreign interventions have been a disaster. And it is good that he wants some closer scrutiny from now onwards. I am not a great fan of military intervention, although I also do not want to rule them out them perennially (as opposed to many others in the liberal tradition). Many of the interventions over the past few decades have lead to nothing though, and created their own follow-up problems. So it’s pretty good if that same Mrs Jones is not likely to lose her son or daughter at the battlefield in some faraway country.

And of course Trump is right in asserting that the government is not ruling the citizens, but is just a service provider on behalf of the people, and fully accountable to them. Sure this is bit more complicated in practise, but it is the only proper principle.

So in these three respects: hail to the new chief! Hopefully he sticks to them and does not screw up too dramatically at all other policy fields.

From the Comments: What is a “National Interest”? (Why not federalism?)

I sympathize with your pro-federation views, but it is admittedly a difficult position to argue from a purist libertarian view. I would support offering statehood to Japan and South Korea, as I mentioned earlier this week.* I would not however offer the same deal to Ukraine or the Baltic states. If pressed why I would be okay with federation with one group of countries but not another is because I consider the Ukraine/Baltic region to have little value to American interests. I can see Japan/South Korea federation helping economic growth and military might to the US and therefore in our interests. Note my use of plural pronouns.

From a purely libertarian basis what regions would you offer federation with? Or, if you’d offer federation to all of them, which regions would you offer federation with first? Taiwan might entertain an offer to join the federation tomorrow, but I suspect the PRC or Russia wouldn’t.

*I imagine they’d join as multiple states in practice. I wouldn’t offer Japan 114 seats in the senate, but I would entertain giving them 10 senators.

Why only ten? Michelangelo’s quibble about the number senators can illustrate why federation is more libertarian than isolationism (I’ll get to his question in just a minute).

The Japanese would never accept any sort of union where they give up some sovereignty for other benefits and only have ten representatives in the senate. That wouldn’t be a bargain for the Japanese; it’d be highway robbery. The key conceptual point to keep in mind in this scenario is that there are two sides bargaining and cooperating with each other in order to arrive at a mutually beneficial deal. Japan and the US cease to exist as sovereign political units but become more secure militarily, economically, and politically through a federation with each other.

Contrast this view with what, say, isolationists such as Doug Bandow or Daniel McAdams argue; they want much less cooperation and, by implication, much less choice. Cooperation would be limited to negotiating trade details, arming factions, and coordinating responses to natural disasters. This is radically different from the status quo, but not in a beneficial way. Think of all the things isolationism and the status quo exclude from their policies. People in Japan and the US are overwhelmingly in favor of a continued US presence in Japan. The reasons for this are clear, but as it stands the Japanese are taking the US for a ride. Isolationist arguments are arguably worse, as they’d remove US troops (angering vast swathes of both societies in the process), which would put Japan in a position to fend for itself. Isolationism is “doing something,” and it’s doing something uncooperative.

I agree wholeheartedly with mainstream libertarians about the unfair nature of the status quo. I just think their proposals are equally unfair (if not worse). A libertarian position should emphasize cooperation, choice, and trade-offs above all else. The current stable of libertarian foreign policy experts don’t do this, despite their pertinent critiques of the status quo.

Now, before I get to Michelangelo’s question of who (I promise it’s coming), I want to spend a little time on his proposal for 10 senators, and tie it into the concept of “national interest,” which is a fuzzy concept and hence popular to wield in public discourse.

What is the national interest (or US interest)?

Think it through and write down your answer on a piece of scratch paper you have lying around.

Go ahead. I’ll wait patiently.

Is your answer really the national interest, though? Why is your definition of the national interest true and Walter Russell Mead’s not? Here is how I defined the concept of a national interest back in 2014:

…the national interest is an excuse [scholars and activists use] for a policy or set of policies that [they believe] should be taken in order to strengthen a state and its citizens (but not necessarily strengthen a state relative to other states…)

Now go back and look at what you wrote down as “the national interest.” Am I right or am I right? There’s no such thing as a national interest. Cooperation, choice, and trade-offs do exist, though, and I think they can walk us through a hypothetical federation between Japan and the US.

Michelangelo rightly decries the fact that Japan, a country with 126 million people in it (California has 40 million) should get 114 senators. Yet 10 senators seems far too few to give up sovereignty for federation. This appears to be a stubborn impasse, right? Wrong! One of the great benefits of cooperation is having to learn new things.

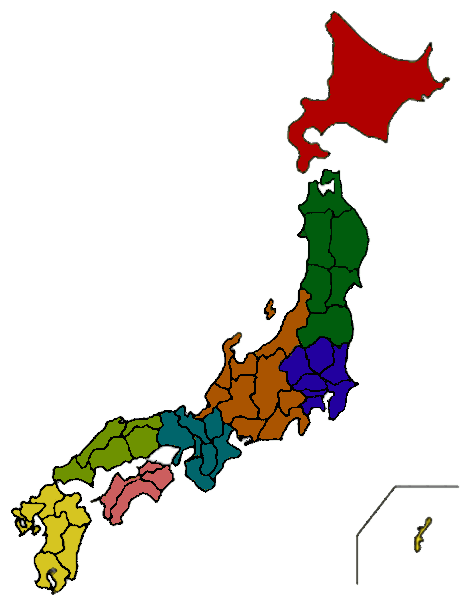

The 47+ prefectures of Japan, for example, have been in use since 1888. The prefectures had steadily been declining in number as the Meiji oligarchy began in earnest to nation-build in what is now Japan. Up until the surrender of Japan to the US, these prefectures were not representative and had little say in how each prefect was to be governed. MacArthur’s constitution gave these 47+ prefectures some autonomy in 1947, but recent attempts at reforming the administrative units of Japan have called for the abolition of these prefectures in favor of fewer administrative units that will also have much more independence from Tokyo. The policymakers who want to take this track are not creating these fewer administrative units out of thin air, either. Rather, reformists are calling for representative units to be based on the unofficial cultural areas of the country that have been around for centuries. Check out the map:

A cooperative approach to tackling free-riding and imperial expenses would be to reach out to the factions that want fewer administrative states with more autonomy. Adding anywhere from 8 to 14 administrative units into the Madisionian system is much more doable than, say, trying to incorporate 47 administrative units, especially since the latter units have little experience with the autonomous governance that federalism requires of its “states.” At most, there would be 28 additional members of the Senate. The costs associated with free-riding would be gone, and the Japanese people would get the benefits of being a part of the most powerful military the world has ever seen.

Would 28 Senate seats be enough to give up sovereignty? I don’t know, but I do know that the status quo is unsustainable and so, too, are current alternatives.

To finally answer Michelangelo’s question (“From a purely libertarian basis what regions would you offer federation with? Or, if you’d offer federation to all of them, which regions would you offer federation with first?”), I’d start with the Canadian provinces and Mexican states (though I would make it clear that any region is welcome to apply for membership). Then I’d approach the Caribbean islands, the administrative units in Western Europe (including the Baltic states but excluding Ukraine), and the administrative units in Japan and South Korea. Good neighbors and military allies.

My reasoning behind this approach is simply that 1) most of these regions are almost as rich as the United States, 2) they have a good history of actually being representative of their constituents, 3) they have a long history of either interacting with the Madisonian system or acknowledging its tremendous benefits, and 4) they have experience with being somewhat autonomous in a federal system (a federal system that is much less liberal than the one found in the US, but a federal system nonetheless).

Again, I’m not opposed to allowing poor regions to apply and join such a federation, but I think they would be less inclined to do so. Why? Because poorer states are more parochial, more protectionist, and more likely to be uncooperative than rich ones. If regions within these poorer states wanted to apply for membership, we should be open to it, but we’d have to recognize that these poorer regions have a long, hard slog ahead of them. They would, for example, have to market reasons for why they should no longer be a part of a poor state, and they’d have to do it under the harsh watch of the said poor state. Not an easy task, to be sure, but it can be done and the Madisonian federation should be open to the idea of picking apart post-colonial states if it means federating with an oppressed (or poorly governed) region.

Why “post-colonial”? Because of Realpolitik. Entertaining applications from the likes of Tibet or Chechnya is too risky. Entertaining applications from Baluchistan or Biafra? I’d have no problem risking the ire of Pakistan or Nigeria if it meant partnering up with people who want a better life and are willing to cooperate in order to get it.

PS: I think the dialogue in the ‘comments’ thread of this 2014 piece is also worth reading in tandem with my thoughts on Michelangelo’s comment here.

Which countries are of US interest?

I was reading my news stream when I noted a blog post from the Cato Institute discussing the silliness of adding Montenegro to NATO. I don’t disagree per se. I certainly don’t see the value of adding Montenegro to NATO, if the purpose of NATO is to protect the US. Nor do I disagree with the general US-libertarian belief that the US has over extended itself in terms of military alliances.

I do wonder though what countries US-libertarians should desire to maintain a military alliance with. A North American military alliance, ranging from Canada to Panama and including the Caribbean, makes sense to me. The Atlantic and Pacific Oceans are our greatest defenses, but I welcome military cooperation from our geographical neighbors.

Beyond there though it gets tricky. Western Europe is certainly rich enough to protect itself. The main reason I am hesitant to leave NATO altogether is the nuclear question. France and the UK are the only European powers with nuclear weapons, but several others are part of NATO’s nuclear sharing program. Should the US leave NATO would these countries seek nuclear weapons for themselves? Would the UK/France provide substitute weapons? Ending military ties with Europe would likely be the easiest option in terms of cutting down on allies.

Japan and South Korea are likewise rich countries, but here too the nuclear question arises. Japan has a cultural aversion to nuclear weapons that I do not see it overcoming in the foreseeable future. South Korea may be willing to use nuclear weapons, but its strained historical relationship with Japan leaves me concerned about the future possibility of a Korean-Japanese alliance to counterweight China PRC. I believe that Japan should be encouraged to modify its constitution to allow its military greater freedom in action and to consider acquiring nuclear weapons of its own. Other nations in the region, such as the Philippines, are outmatched in conventional weaponry or, in the case of Australia, too far away geographically to be of much use in restraining China PRC’s influence in east Asia.

I am hopeful that within my lifetime China PRC will transition to a liberal democracy, but till then I am skeptical about allowing it free reign in east Asia. For the foreseeable future it is hard for me to consider an east Asia without a significant role for the US. Nor would I be particularly against offering South Korea and/or Japan statehood in a United States of the Pacific.

Thoughts? I admit that international politics is not my area of expertise and I more than welcome other’s thoughts on the matter. I also admit that I am not viewing these issues from a pure libertarian perspective but with a splash of nationalism.

As readers may know our own Brandon is playing around with creating a NOL foreign policy quiz similar to the Nolan libertarian quiz.

From the Comments: Western Military Intervention and the Reductio ad Hitlerum

Dr Khawaja makes an excellent point in the threads of my post the libertarianism of ISIS:

As for the Hitler comparison, I think that issue really needs to be opened and discussed from scratch. One relatively superficial problem with the Hitler/ISIS analogy is that ISIS is not plausibly regarded as the threat to us that Nazi Germany was, or could have been. But at a deeper level: instead of regarding war with Nazi Germany as beyond question, we ought to be able to ask the question why it was necessary to go to war with them. Once we grasp that nettle, I think the Hitler comparisons really lead in one of three directions: either they show us how different the Nazi regime was from ISIS, or they cast doubt on the “need” to fight the Nazis in the first place, or they prove that we “had” to fight the Nazis only because we put ourselves on a path that made fighting inevitable. But we shouldn’t walk around with the axiom that if x resembles the Nazis, well, then we better fight x…or else we’re dishonoring our forbears. Which is about the level of neo-conservative discussion on this topic.

The reason why we went to war with Nazi Germany is that the Nazis (credibly) declared war on us after we declared war on Japan–after Japan attacked us at Pearl Harbor (after we challenged Japanese imperialism in East Asia…etc.). Granted, there was naval warfare in the Atlantic before December 1941, but we might have avoided that by not supporting Britain (and the USSR) against the Nazis in the first place. War with the Nazis became an inevitability because of our prior involvement in a European quarrel, not because of the unique turpitude of the Nazis (much less because of the Holocaust). I don’t mean to deny that the Nazis were uniquely evil. I mean: that’s not why we fought. The reasons we fought were highly contingent, and might, given different contingencies, have led to not fighting at all.

The preceding suggestion seems off-limits to some, but I don’t think it is. Suppose we had not supported Britain in 1940-41, not had a Lend-Lease program (“An Act to Further Promote the Defense of the United States”), and the Nazis had not declared war on us after Pearl Harbor. Was war with them necessary or obligatory? I don’t see why. If we could go decades without hot war with the USSR or China, why not adopt a similar policy vis-a-vis Germany? (Yes, Korea involved some hot war with China, but my point is: we could have avoided that, too.) And if there is no good case for war with the Nazis under a consistently isolationist policy, the Hitler comparisons in the ISIS case are worse than useless.

What we have in the ISIS case is just an exaggerated version of the “inevitabilities” that got us into war with Germany. By overthrowing Saddam Hussein, we ourselves created the path dependency that gives the illusion of requiring war against ISIS as a further “correction.” In that sense, the Hitler comparison is quite apt, but entails the opposite of what the hawks believe. We’re being led to war to correct the disasters created by the last war, themselves intended to correct the problems of the war before. Isn’t it time to stop digging? Perhaps we shouldn’t have gotten onto any of these paths. The best way to avoid traveling down the highway to hell is to take an exit ramp and get the hell off while you still can. Not that you’re disagreeing, I realize.

Indeed. Be sure to check out Dr Khawaja’s blog, too (I tacked it on to our blogroll as well). My only thoughts are additions, specifically to Irfan’s point about taking an exit ramp. I don’t think there are enough libertarians talking about exit ramps. There are plenty of reactions from libertarians to proposals put forth by interventionists, but there are precious few alternatives being forth by libertarians. Dr van de Haar’s (very good) point about alliances is one such alternative. (I wish he would blog more about this topic!) Another option is to initiate deeper political and economic ties with each other (through agreements like political federations or trading confederations). Libertarians rarely write or talk about realistic alternatives to military intervention, especially American ones.

From the Comments: Military Alliances and the Free Rider Problem

Dr van de Haar’s excellent post on secession and alliances prompted the following from yours truly:

I think you highlight well the difference in opinion, on foreign policy, between libertarians/classical liberals in Europe and the United States. Alliances are sometimes a good option, and it pains me to see American libertarians dogmatically reject alliances in a spirit of reaction.

At the same time, European libertarians have yet to acknowledge a problem as old as Thucydides’ writings on the Delian League: that of free-riding. As NATO stands today, the European partners in the alliance (save for the UK and some newer, Eastern members) have been taking the US taxpayer for a ride.

This is a small injustice in the grand scheme of things, but it is an injustice nonetheless. The problem of alliances and free-riding extends far beyond NATO, of course. This is why I argue that alliances should be eschewed in favor of federations. I got this this idea from the likes of Ludwig von Mises, Adam Smith, and FA Hayek. The logic behind opting for federation over alliance runs something like this: if two or more countries can pledge mutual military aid to each other, but cannot abide forging closer economic and political ties, then the likelihood of each member of the alliance adhering to an agreed-upon charter is going to be very low.

Federation gets around this problem. Isolationism and empire do not.

Be sure to check out the back-and-forth between Edwin and General Magoon, too.

Secession and international alliances go together

It is important to scrutinize the intellectual strength of libertarian ideas about international relations. Here are a few – admittedly only partly systematic- thoughts about the relation between secession and international relations. Or more precise: some libertarians are positive about secession, yet at the same time negative about international alliances. How does that relate?

Pleas for secession can be found in the works of Von Mises, Rothbard, Hoppe and other luminaries of libertarian thought, broadly defined. In an informative chapter on the issue, Mises-biographer Jörg Guido Hüllsman (at mises.org) defined secession as the ‘one-sided disruption of (hegemonic) bonds with a larger organized whole to which the secessionists have been tied’. Recent examples are the bloody secessions of South Sudan or Eritrea. Yet the issue also remains topical in Western Europe, for example in Scotland. It is not my purpose to emphasize the practical failures and wars associated with secession. From a libertarian perspective the principal benefit of secession is that a group of sovereign individuals decide for themselves how and by whom they are governed, and in which type of regime this shall happen. So far, no problem.

Let’s assume a world where secessions take place freely, peacefully and more frequent than in the past twenty-five years, where the number of sovereign states just went up by approximately twenty recognized independent countries. The logical result will be the fragmentation of the world in numerous smaller states, or state-like entities, of different sizes, composed of different groups of people. Perhaps some of these states will comply to an anarcho-capitalist libertarian ideal, so with a strict respect for property rights and the use of military defense only for clear-cut violations of these rights by others. However, it is unlikely that all states will be characterized in this way. Consequently, there remain a lot of causes for international conflict and war. For example, as there are more borders, there are also potentially more border disputes, about natural resources, water, stretches of land, et cetera. Of course humans are not angels, and no libertarian ever claims they will be. It simply means none of the other causes of war are perpetually eradicated in a world of free secession either.

So how to defend oneself in such situation, particularly when your state is much smaller than one or more other states in the vicinity? In such a situation you are unable to defend yourself against the most viable threats. Even if you declare yourself a neutral state it is unlikely this will always be respected. After all, it takes at least two to tango in international politics. Of the many possibilities to defend your property rights and sovereignty, the negotiation of agreements with other countries, or joining an international alliance seems logical and potentially beneficial (of course depending on the precise terms). It would amount to a system of multiple balances of power around the globe, very much like for example former Cato Institute scholar Ted Galen Carpenter favored for the current world. Surely, this would not be ideal, and would not be able to eradicate war either. Yet it will prevent many wars and safeguard the liberties and property rights of the participants.

This differs significantly from the pleas by people who simultaneously favor secession while calling for a non-interventionist foreign policy without alliances, such as Rothbard, Ron Paul (see for example in a column), or many contributors on www.lewrockwell.com.

Admittedly, most of these anti-alliance commentaries are directed against particular parts of current US foreign policy. However, it is still fair to demand theoretical consistency. Either these writers overlook there might be an problem, or they choose to ignore it. Still it is important to acknowledge there is an issue here. It is too simple to reject international alliances while embracing secession at the same time.

Romney and “Defense”

“If you don’t want America to be the strongest nation in the world, I’m not your President.” Thus spake candidate Romney recently. Well, I don’t and he’s not.

Sure, you could interpret “strongest” to mean most prosperous, fairest, etc. But we all know darn well what Mitt, who is pals with the Zionist militant Netanyahu, had in mind: military might.

Of all the urgently needed reforms in this country, I submit that dismantling the empire is #1. It is bankrupting us, generating enemies for us, and turning our homeland into a police state.

Yes, I said empire. Depending on how you count, there are as many as 737 US military bases scattered across the globe, about 38 of which are medium- to large sized. The number of military and other government personnel involved plus private contractors runs into the millions. The CIA is hated all over the world and for good reasons. And as Brandon Christensen pointed out, the US defense umbrella weakens incentives for the Europeans, Japanese, et. al., to take care of themselves.

Obama’s record on these matters is mixed. The good news: the Iraq war has ended (for the present; keep your fingers crossed), Afghanistan is winding down, and cuts in the “defense” budget are coming. On the other side of the ledger, there have been ominous buildups in Australia and Central Africa. On the home front, the police state is escalating and the spiral toward bankruptcy is accelerating. A pretty awful report card in all, yet Romney could make it worse.

No, I haven’t lost my senses. I will not vote for Obama, who I believe to be hell-bent for fascist dictatorship, in consequence if not by conscious design. If you forced me to choose between him and Romney I would cross my arms and refuse to choose. I’m voting for Gary Johnson, who has called for a 43% cut in “defense” spending.

The Future of NATO

The recent NATO summit in Chicago that produced absolutely nothing has opponents of the alliance smelling blood. Indeed, the only thing that the Chicago summit may have produced is a healthy recognition by many factions that the future of NATO itself is increasingly in doubt. This should come as no surprise to any of us here at the Notewriter’s consortium, but in some ways this development is surprising.

Even mainstream pundits, ensconced as they are in Beltway ideology, have begun to notice that the alliance is on its way out. From CNN’s Security Clearance blog (“security clearance”? Really?):

Europe’s collective fatigue with NATO’s globetrotting has often left the United States shouldering most of the burden, which is considered one of NATO’s greatest shortcomings. The United States now covers 75% of NATO defense budgets, while the majority of allies don’t even allocate NATO’s benchmark 2% of gross domestic product to defense.

Sharp reductions in European defense budgets have only increased dependence on the United States.

While realists have been bemoaning the alliance for decades, it has become apparent that the reality of the situation has finally smacked some sense into the Beltway consensus. This must be kind of like how libertarians felt after the collapse of the Berlin Wall in the late 1980’s.

Like the collapse of the Soviet Union, though, there are many things to be worried about with the impending collapse of NATO. The major issue that the US should be worried about is deteriorating relations with Europe. While the American taxpayer got stuck subsidizing the defense of Europe for well over half a century, the relationships brought about by working together have proved fruitful, and in order to keep these relations on good terms, Washington should undertake policies that will further integrate American and European societies: freer trade.

with the impending collapse of NATO. The major issue that the US should be worried about is deteriorating relations with Europe. While the American taxpayer got stuck subsidizing the defense of Europe for well over half a century, the relationships brought about by working together have proved fruitful, and in order to keep these relations on good terms, Washington should undertake policies that will further integrate American and European societies: freer trade.

There is no reason why there shouldn’t be a free trade zone between the whole of the US and Europe on the scale of the US itself or the EU (the same goes for the US and its nearest neighbors: Canada, Mexico, and the Caribbean).

One thing that American policymakers should not fear is the rise of a competitor in the form of a European superstate. This fear (or hope, if you are an American socialist) is off-base. Just think of Europe’s sclerotic answers to the worst economic crisis in its history, and then imagine a European Union trying to implement a common, cohesive foreign policy on a global scale like that of the US.

It isn’t possible. Not even states with highly centralized power structures like China can compete with the US in this regard, and the thought of Brussels actively trying to compete with the US in international relations is ludicrous.

The demise of NATO is ultimately a good thing. There is no need for a collective security alliance to combat a menacing Russia any longer. Moscow’s empire of Soviets is long gone, and its focus in the near future will be domestic and along its borders. NATO’s demise will also save the US a lot of money, and will spare the European people from the negative effects (like terrorist attacks) associated with supporting a worldwide hegemon. We can only hope that NATO’s demise comes sooner rather than later, and that each party involved will recognize that continued relations with each other, especially in regards to trading policy, are still vital to peace and prosperity.