- The managerial state and rule by the perfectly unjust man Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

- What do left-liberal abusers really think? Bryan Caplan, EconLog

- Cthulhic tendrils lubricated by oil Xenogoth

- How Robert E. Lee’s home became Arlington National Cemetery Rick Brownell, Historiat

Turkish Elections: Some Hope

What with being rather exhausted by an accumulation of projects in recent months, I have been extremely absent from Notes On Liberty. Teaching is over for the summer and I hope to make up for lost ground across a few areas, but first I must address the current situation in Turkey.

There will be early elections on 24th June for the National Assembly and the Presidency. If no candidates win an overall majority for the presidency, there will be a run off between the two leading candidates on 8th July. The National Assembly is elected through proportional representation (d’Hondt system, if you’re interested in the details). The elections were scheduled for November next year, so they are very early. The reason offered by the government is the need to complete the transition to a strongly presidential system in view of supposed administrative uncertainty interfering with government until the last stage of the constitutional change, which is triggered by the next election after last year’s constitutional referendum, and the supposed need for ‘strong’ presidential government to deal with the present situation in Syria and Iraq.

However, anyone who is not a hopelessly naive follower of regime publicity knows that the real reasons are the decline in the economy and the rise of a right-wing party opposed to the current regime, which could erode the regime’s electoral base. I use the term ‘regime’ deliberately to refer to the fusion of the AKP (dominant political power), the personalised power of President Erdoğan and the state apparatus, including the judiciary. There is no state independent of a party power which itself has become subordinate to the will of one man. The police, judiciary, and prosecution service are quite obviously biased towards the government. Civil society has not escaped the hegemonising pressure. All the main media companies are controlled by cronies of Erdoğan and the AKP. Both state media and the main commercial media present a government point of view with little coverage of the opposition. Private media companies are of course entitled to push their own opinions, but these opinions are in reality dictated by Erdoğan, with the calculated intention of excluding opposition points of view except in highly parodic and manipulated terms. The construction industry is forced to support Erdoğan in order to obtain contracts for the endless pubic projects and projects officially or de facto guaranteed by the tax payer. This instrument of political control is enhanced through endless, often grandiose projects regardless of the state of public and private debt. In this politics, interest rates are artificially low with the consequence that inflation is rising and the currency is constantly devalued in international markets.

A lot of the above will be already understood by readers, but particularly after a long break in writing I think it is important to set the scene for the elections. Whatever the AKP says in public about economic performance, officials have admitted in private that they are worried about an economic crisis before the regular date for the elections. It is also clear that the AKP hoped to keep the new right-wing party IYI (Good) out of the elections because of the complex registration process to participate in elections, amongst other things requiring registration of a minimum number of provincial branches. IYI is a break away from the well established Nationalist Action Party (MHP), and is already larger in members with more opinion poll support, so its exclusion would be particularly absurd.

The IYI Party’s problems with registration were resolved in ways that are part of the hope that does exist in this election. The main opposition party (and oldest party in Turkey), the leadership of the Republican People’s Party (CHP), which has a left-wing and secularist identity, allowed (or maybe insisted) that enough of its deputies in the National Assembly join the small group of IYI defectors from the MHP to guarantee an automatic right to electoral participation.

President Recep Tayyıp Erdoğan was only able to change the constitution to make it a very strongly presidential system, rather than a parliamentary system as it had been, because the MHP changed its position after years of critcising Erdoğan. The pretext was ‘unity’ after the attempted coup of 2016, though it was clear the whole country was against it anyway. The real reason was that the MHP has been losing support under a leader who has become unpopular and the only hope of staying in the National Assembly, given a 10% threshold, was an electoral deal with the AKP (which stands for Justice and Development Party). The election law was changed so that parties can form joint electoral lists in which voters can choose between parties in the list when voting, and the party concerned can have deputies so long as the votes within the list allow at least one to get into the National Assembly. In effect, the percentage threshold to enter the National Assembly has been reduced to less than 1%. This seemed to the AKP to be a great achievement allowing them to compensate for declining support of both AKP and MHP by joining them in one list and bringing in another small nationalist party.

However, the opposition has moved to make more use of the new rules. The CHP and IYI have formed a joint list, which also include SP (Felicity Party), a religious conservative party which has common roots with the AKP and is the sixth party in Turkey in support (about 2.5 % in recent polls). A small centre right party has candidates on the IYI list within the joint list. The Liberal Democrat Party, which is classical liberal and libertarian in orientation, but is very small, has a candidate who used to be LDP leader on the CHP list within the list. This is a bit complicated, but the success of putting this complex alliance together shows there is hope of various forces opposed to the authoritarian slide for various reasons uniting around common goals of a more restrained state, rule of law, less personalisation of power and a more consensual institutionally constrained style of government.

The other important force is HDP (People’s Democratic party), itself an alliance of small leftist groups with a Kurdish identity and leftist party which has strong support in the southeast. The HDP promotes peace in the southeast through negotiation between the state and the PKK (Kurdistan Workers’ party) armed insurgent/terrorist group. There is no organic link I can see between the HDP and the PKK, but the overlapping aims of the PKK and HDP for Kurdish autonomy and political recognition of the PKK has always made it easy to label the HDP as terrorist. It is simply not possible in these circumstances to include it in a broad opposition list, particularly given the attempts of the regime to block the HDP from any political activity: labeling it “terrorist,” arresting its leaders and many mayors leading to central government take over of HDP municipalities in the southeast. However, the opposition on current poll ratings needs the HDP to get past the 10% threshold to deprive the AKP-MHP list of a majority in the National Assembly. The main list might do it on its own, but this is less than certain. There is a risk of electoral rigging influencing the result, particularly in the southeast which is under even more authoritarian security state conditions than the rest of the country. It is therefore important for the HDP to get clearly more than 10% and to get votes from people who might otherwise vote CHP, outside the southeast to get pass any dirty tricks.

This is already long so I will stop and return to the Turkish elections soon. I hope readers have got to the end of this and have a reasonable background now for future posts.

Divergence and Convergence within Italy

Two years, I wrote a post on this blog on the process of regional convergence in Italy. In that post, I made the observation that it seems that, economically, Italy was as fragmented at the time of the unification as it is today which made it an oddity in terms of regional convergence. To make that claim, I used this table of relatively sparsed out observations produced by Emanuele Felice: which was published in the Economic History Review:

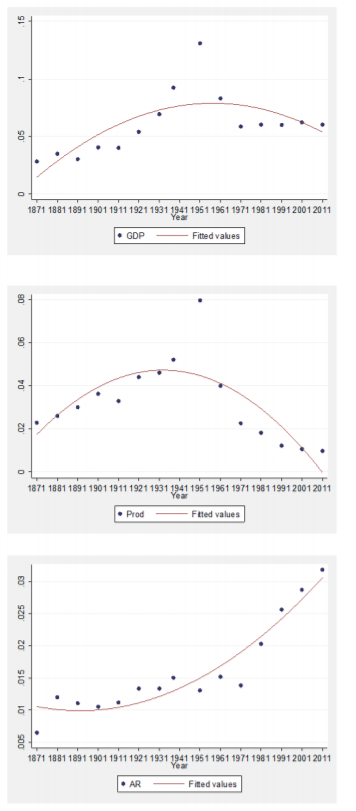

As one can see, there is a pronounced “lack” of integration for the Italy in terms of living standards. This is reinforced by a more “continuous” set of estimates produced, again, by Emanuele Felice (this time, its a working paper of the Bank of Italy) that now include the 1870s and go to 2011 (as opposed to 2001). This is the result, which I find fascinating. The first graph shows GDP per capita – for which there is divergence to 1951 and then a mild convergence thereafter but still well above the levels at the time of unification. More fascinating is the fact that productivity is at its most integrated since unification (2nd figure) suggesting a divergence in levels of labor activity (3rd figure). In these three graphs, you have a neat summary of Italian labor markets since 1870.

Nightcap

- Lost in translation: Native American mascots in Europe Andrew Keh, NY Times

- Zanele Muholi: The dark artist of South Africa Mark Gevisser, 1843

- Aristocrats have always been internationalist Blake Smith, Aeon

- Frayed transatlantic ties are weakening NATO Azita Raji, War on the Rocks

Jordan Peterson’s Ignorance of Postmodern Philosophy

Up until this point, I’ve avoided talking about Jordan Peterson in any serious manner. In part because I thought (and continue to hope) that he’s the intellectual version of a fad diet who will shortly become irrelevant. My general impression of him is that when he’s right, he’s saying rather banal, cliché truisms with an undeserved bombastic air of profundity, such as his assertions that there are biological differences between men and women, that many religious myths share some similar features, or that taking personal responsibility is good. When he’s wrong, he’s talking way out of the depth of his understanding in his field (like the infamous lobster comment or this bizarre nonsense). Either way, it doesn’t make for a rather good use of time or opportunity for interesting, productive discussion—especially when his galaxy-brained cult-like fanboys are ready to pounce on anyone who criticizes their dear leader.

However, since everyone seems to be as obsessed with Jordan Peterson as he is with himself, I guess it’s finally time to talk about one example of him ignorantly bloviating that particularly annoys me as a philosophy student: his comments on postmodernism. There’s a lot one can talk about with Jordan Peterson because he says almost anything that comes to his mind about any topic, but for the present purposes you can pretend that I think everything he’s ever said that isn’t about postmodern is the deepest, most insightful thing ever said by any thinker in the history of western thought. I’m not interested in defending any overarching claims about him as a thinker. At the very least, his work on personality psychology does seem rather well respected and he surely got to his prestigious academic position with some merit, though I am not qualified to really appraise it. I am, however, more prepared to talk about his rather confused comments on philosophy which might shed light on why people are generally frustrated with his overly self-confident presence as a public intellectual.

Postmodernism, According to Peterson

Peterson often makes comments about “postmodern neo-Marxism,” which he calls a “rejection of the western tradition.” Now the very phrase “postmodern neo-Marxism” strikes anyone remotely familiar with the academic literature on postmodernism and Marxism as bizarre and confused. Postmodernism is usually characterized as skepticism towards grand general theories. Marxism is a grand general theory about how class struggle and economic conditions shape the trajectory of history. Clearly, those two views are not at all compatible. As such, much of the history of twentieth century academia is a history of Marxists and postmodernists fighting and butting heads.

Many commentators have pointed out this error, but Jordan Peterson now has a response. In it he tries to offer a more refined definition of postmodernism as two primary claims and a secondary claim:

Postmodernism is essentially the claim that (1) since there are an innumerable number of ways in which the world can be interpreted and perceived (and those are tightly associated) then (2) no canonical manner of interpretation can be reliably derived.

That’s the fundamental claim. An immediate secondary claim (and this is where the Marxism emerges) is something like “since no canonical manner of interpretation can be reliably derived, all interpretation variants are best interpreted as the struggle for different forms of power.”

He then goes on to concede to the criticism that Marxism and postmodernism can’t be described as theoretically aligned, but moves the goal posts to say that they are practically aligned in politics. Further, he contends postmodernisms’ commitment to analyze power structures is just “a rehashing of the Marxist claim of eternal and primary class warfare.”

It is worth noting that this attempt at nuance is surely an improvement at Peterson’s previous comments that postmodern a Marxism are a coherent “doctrine” that just hated logic and western values. But his attempt at a “definition” is unsatisfactorily way too restrictive for every thinker who gets called “postmodern,” and the attempt to link the politics of postmodernism up with the politics of Marxism is a complete mischaracterization. Further, his attempt to “critique” this position, whatever one wants to call it, is either (at best) vague and imprecise or (at worst) utterly fails. Finally, there really is no alliance between postmodernists and Marxists. Whether or not a thinker is called a “postmodernist” or not is not a very good predictor of their political views.

Why Peterson’s Definition isn’t what Postmodernists Believe and his Critique Fails

First of all, I am really not interested in dying on the hill of offering a better “definition” of postmodernism. Like any good Wittgensteinian, I tend to think you can’t really give a good list of necessary and sufficient conditions that perfectly captures all the subtle ways we use a word. The meaning of the word is the way it is used. Even within academia postmodernism has such broad, varied usage that I’m not sure it has a coherent meaning. Indeed, Foucault once remarked in a 1983 interview when asked about postmodernism, “What are we calling postmodernity? I’m not up to date.” The best I can give is Lyotard’s classic “incredulity toward metanarratives,” which is rather vague and oversimplified. Because this is the best I think one can do given how wildly unpredictable the usage of postmodernism is, we’re probably better off just not putting too much stock in it either as one’s own philosophical position or as the biggest existential threat to western civilization and we should talk about more substantive philosophical disagreements.

That said, Jordan Peterson’s definition is unsatisfactory and shows a poor understanding of postmodernism. While the first half of the fundamental claim is a pretty good stab at generalizing a view most philosophers who get labeled as postmodern agree with, the second half is rather unclear since it’s uncertain what Peterson means by “canonical.” If he takes this to mean that we have no determinate way of determining which interpretations are valid, then that would be a good summary of most postmodernists and an implication of Peterson’s own professed Jamesian pragmatism. If what he thinks it means is that all perspectives are as valid as any other and we have no way of deciphering which ones are better than the other, then nobody relevant believes that.

Peterson objects to is the implication “that there are an unspecifiable number of VALID interpretations.” He tries to refute this by citing Charles Pierce (who actually did not at all hold this view) and William James on the pragmatic criterion of truth to give meaning to “valid interpretations.” He says valid means “when the proposition or interpretation is acted out in the world, the desired outcome within the specific timeframe ensues.” However, it doesn’t follow from this view that you can specify the number of valid interpretations. It just begs the question of how we should understand what “the desired outcome” means, which just puts the perspectivism back a level. Even if we did agree on a determinate “desired outcome,” there are still multiple beliefs one could have to achieve a desired outcome. To put it in a pragmatically-minded cliché, there is more than one way to skin a cat. This is why, in fact, William James was a pluralist.

Perhaps by “specifiable,” he doesn’t mean we can readily quantify the number of valid interpretations, just that the number is not infinite. However, nobody believes there are an infinite number of valid perspectives we should consider. The assertion that a priori we cannot quantify the number of valid perspectives does not mean that all perspectives are equally valid or that there are an infinite number of valid perspectives. Peterson’s argument that we have limited cognitive capacities to consider all possible perspectives is true, it’s just not a refutation of anything postmodernists believe. On this point, it is worth quoting Richard Rorty—one who was both a Jamesian pragmatist and usually gets called postmodern—from Philosophy and the Mirror of Nature:

When it is said, for example, that coherentist or pragmatic “theories of truth” allow for the possibility that many incompatible theories would satisfy the conditions set for “the truth,” the coherentist or pragmatist usually replies this merely shows that we have no grounds for choice among thse candidates for “the truth.” The moral to draw is not to say they have offered inadequate analyses of “true,” but that there are some terms—for example, “the true theory,” “the right thing to do”—which are, intuitively and grammatically singular, but for which no set of necessary and sufficient conditions can be given which will pick out a unique referent. This fact, they say, should not be surprising. Nobody thinks that there are necessary and sufficient conditions which will pick out, for example, the unique referent of “the best thing for her to have done on finding herself in that rather embarrassing situation,” though plausible conditions can be given as to which will shorten a list of competing incompatible candidates. Why should it be any different for the referents of “what she should have done in that ghastly moral dilemma” or “the Good Life for man” or “what the world is really made of?” [Emphasis mine]

The fact that we cannot readily quantify a limited number of candidates for interpretations or decide between them algorithmically does not that we have absolutely no ways to tell which interpretation is valid, that all interpretations are equally valid, nor does it mean there are an infinite number of potentially valid interpretations. Really, the view that many (though not all) postmodernists actually hold under this “primary claim” is not all that substantially different from Peterson’s own Jamesian pragmatism.

As for the secondary claim, which he thinks is Marxist, that “since no canonical manner of interpretation can be reliably derived, all interpretation variants are best interpreted as the struggle for different forms of power.” This view is basically just one just Foucault might have held depending on how you read him. Some would argue this isn’t even a good reading of Foucault because such sweeping generalizations about “all interpretations” is rather uncharacteristic of a philosopher who’s skeptical of sweeping generalizations. However, you read Foucault (and I’m not really prepared to take a strong stand either way), it certainly isn’t the view of all postmodernists. Rorty criticized this habit of Foucault (Contingency, Irony, and Solidarity, p. 63), and thought that even if power does shape modern subjectivity it’s worth the tradeoff in the gains to freedom that modern liberalism has brought and thus is not the best way to view. It’s also telling that Peterson doesn’t even try to critique this claim and just dogmatically dismisses it.

Postmodernism’s Alleged Alliance with Marxism

So much for his vague, weak argument against a straw man. Now let’s see if there’s any merit to Peterson’s thought that Marxism and postmodernism have some important resemblance or philosophical alliance. Peterson says that the secondary claim of postmodernism is where the similarity to Marxism comes. However, Marx simply did not think that all theories are just attempts to grab power in the Foucauldian sense: he didn’t think that dialectical materialism the labor theory of value were just power grabs, and predicted a day when there was no competition for power in the first place at the end of history since a communist society would be classless. If anything, it’s the influence of Nietzsche’s Will to Power on Foucault, and oddly enough Peterson thinks rather highly of Nietzsche (even though Nietzsche anticipated postmodernism in rather important ways).

The only feature that they share is a narrative of one group trying to dominate another group. But if any attempt to describe oppression in society is somehow “Marxist,” that means right libertarians who talk about how the state and crony capitalist are oppressing and coercing the general public are “Marxist,” evangelicals who say Christians are oppressed by powerful liberal elites are “Marxist,” even Jordan Peterson himself is a “Marxist” when he whines about these postmodern Marxist boogeymen are trying to silence his free speech. He both defines “postmodernism” too narrowly, and then uses “Marxism” in such a loose manner that it basically means nothing.

Further, there’s Peterson’s claim that due to identity politics, postmodernists and Marxists now just have a practical political alliance even if it’s theoretically illogical. The only evidence he really gives of this alleged “alliance” is that Derrida and Foucault were Marxists when they were younger who “barely repented” from Marxism and that courses like critical theory and gender studies read Marxists and postmodernists. That they barely repented is simply a lie, Foucault left all his associations with Marxist parties and expunged his earlier works of Marxist themes. But the mere fact that someone once was a Marxist and then criticized Marxism later in their life doesn’t mean there was a continuing alliance between believers in their thought and Marxism. Alasdair MacIntyre was influenced by Marx when he was young and became a Catholic neo-Aristotelian, nobody thinks that he “barely repented” and there’s some overarching alliance between traditionalist Aristotelians and Marxists.

As for the claim that postmodernists and Marxists are read in gender studies, it’s just absurd to think that’s evidence of some menacing “practical alliance.” The reason they’re read in those is mostly courses is to provide contrast for the students of opposing perspectives. This is like saying that because Rawlsian libertarians are taken seriously by academic political philosophers there’s some massive political alliance between libertarians and progressive liberals.

Really, trying to connect postmodernism to any political ideology shows a laughably weak understanding of both postmodernism and political theory. You have postmodernists identifying as everything from far leftists (Foucault), to progressive liberals (Richard Rorty), to classical liberals (Deirdre McClosky), to anarchists (Saul Newman), to religious conservatives (like Peter Blum and James K.A. Smith). They don’t all buy identity politics uniformly, Richard Rorty criticized the left for focusing on identity issues over economic politics and was skeptical of the usefulness of a lot of critical theory. There really is no necessary connection between one’s highly theoretical views on epistemic justification, truth, and the usefulness of metaphysics or other metanarratives and one’s more concrete views on culture or politics.

Now Peterson can claim all the people I’ve listed aren’t “really” postmodern and double down on his much narrower, idiosyncratic definition of postmodernism which has very little relation to the way anyone who knows philosophy uses it. Fine, that’s a trivial semantic debate I’m not really interested in having. But it does create a problem for him: he wants to claim that postmodernism is this pernicious, all-encompassing threat that has consumed all of the humanities and social sciences which hates western civilization. He then wants to define postmodernism so narrowly that it merely describes the views of basically just Foucault. He wants to have his cake and eat it too: define postmodernism narrowly to evade criticism that he’s using it loosely, and use it as a scare term for the entire modern left.

Peterson’s Other Miscellaneous Dismissals of Postmodernism

The rest of what he has to say about postmodernism is all absurd straw men with absolutely no basis in anything anyone has ever argued. He thinks postmodernists “don’t believe in logic” when, for example, Richard Rorty was an analytic philosopher who spent the early parts of his career obsessed with the logic of language. He thinks they “don’t believe in dialogue” when Rorty’s whole aspiration was to turn all of society into one continuous dialogue and reimagine philosophy as the “conversation of culture). Or that they believe “you don’t have an individual identity” when K. Anthony Appiah, who encourages “banal ‘postmodernism’” about race, believes that the individual dimensions of identity are problematically superseded by the collective dimensions. This whole “definition and critique” of postmodernism is clearly just a post-hoc rationalization for him to continue to dishonestly straw man all leftists with an absurd monolithic conspiracy theory. The only people who are playing “crooked games” or are “neck-deep in deceit” are ignorant hucksters like Peterson bloviating about topics they clearly know nothing about with absurd levels of unmerited confidence.

Really, it’s ironic that Peterson has such irrational antipathy towards postmodernism. A ton of the views he champions (a pragmatic theory of truth, a respect for Nietzsche’s use of genealogy, a naturalist emphasis on the continuity between animals and humans, etc.) are all views that are often called “postmodern” depending on how broadly one understands “incredulity towards metanarratives,” and at the very least were extremely influential over most postmodern philosophers and echoed in their work. Maybe if Peterson showed a fraction of the openness to dialogue and debate he dishonestly pretends to have and actually read postmodernists outside of a secondary source, he’d discover a lot to agree with.

[Editors note: The last line has been changed from an earlier version with an incorrect statement about Peterson’s source Explaining Postmodernism.]

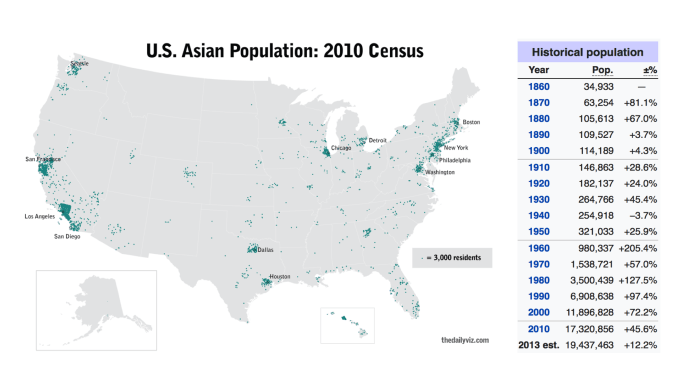

Eye Candy: the US Asian population, circa 2010

“Asian” is a pretty broad term. Racial classifications are, perhaps, the dumbest thing in the world.

Imagine seeing something like this in the press today, or this as an advertisement. There’s been lots of progress in this country, it’s just hard to see sometimes.

Nightcap

- Chinese view of Germany’s rise Francis Sempa, Asian Review of Books

- The lost kingdom of Kush James MacDonald, JSTOR Daily

- Purges and Paranoia in Erdoğan’s ‘new’ Turkey Ella George, London Review of Books

- The British Empire strikes back Colin Kidd, New Statesman

The great global trend for the equality of well-being since 1900

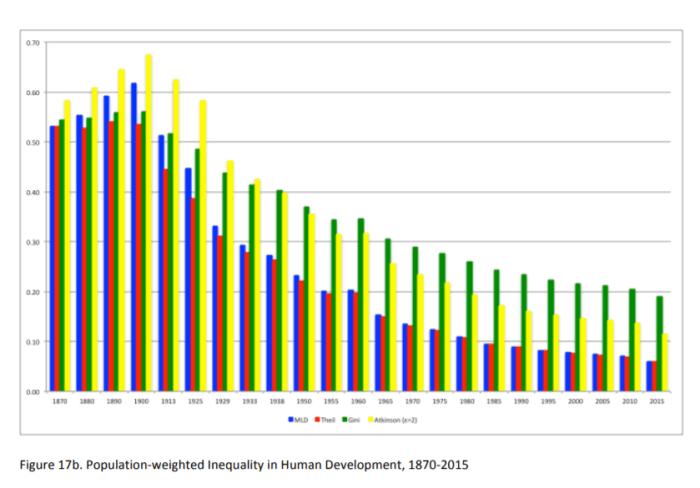

Some years ago, I read The Improving State of the World: Why We’re Living Longer, Healthier, More Comfortable Lives on a Cleaner Planet by Indur Goklany. It was my first exposition to the claim that, globally, there has been a long-trend in the equality of well-being. The observation made by Goklany which had a dramatic effect on me was that many countries who were, at the time of his writing, as rich (incomes per capita) as Britain in 1850 had life expectancy and infant mortality levels well superior to 1850 Britain. Ever since, I accumulated the statistics on that regard and I often tell my students that when comes the time to “dispell” myths regarding the improvement in living standards since circa 1800 (note: people are generally unable to properly grasp the actual improvement in living standards).

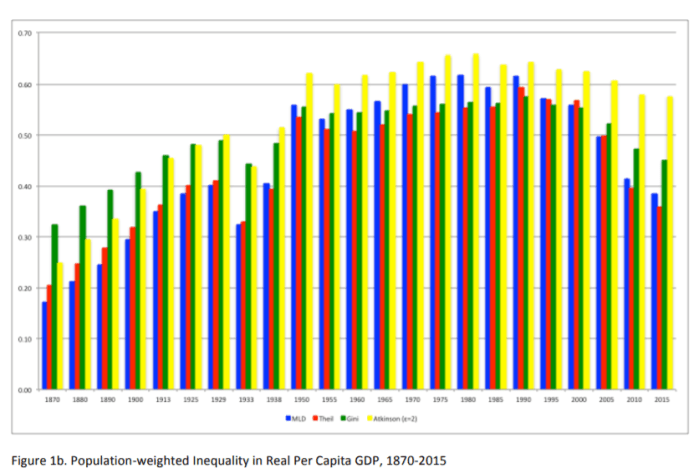

Some years after, I discovered the work of Leandro Prados de la Escosura who is a cliometrician who (I think I told him that when I met him) influenced me deeply in my work regarding the measurement of living standards and who wrote this paper which I will discuss here. His paper, and his work in general, shows that globally the inequality in incomes has faltered since the 1970s. That is largely the result of the economic rise of India and China (the world’s two largest antipoverty programs).

However, when extending his measurements to include life expectancy and schooling in order to capture “human development” (the idea that development is not only about incomes but the ability to exercise agency – i.e. the acquisition of positive liberty), the collapse in “human development” inequality (i.e. well-being) precedes by many decades the reduction in global income inequality. Indeed, the collapse started around 1900, not 1970!

In reading Leandro’s paper, I remembered the work of Goklany which had sowed the seeds of this idea in my idea. Nearly a decade after reading Goklany’s work well after I fully accepted this fact as valid, I remain stunned by its implications. You should too.

Nightcap

- Modernism without industrialism Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

- Adam Smith’s suspicions about democracy Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Left-wing nostalgia Sean Cashbaugh, H-socialisms

- The importance of Richard Pipes (RIP) Jacob Heilbrunn, National Interest

Nightcap

- Antarctica’s long, dark winter Sarah Laskow, Atlas Obscura

- The worst volcanic eruption in US history Rick Brownell, Historiat

- Aftershocks from the 2008 Sichuan earthquake Ian Johnson, NY Review of Books

- Put the “human” back into human capital Parag Khanna, Strait Times

Economists vs. The Public

Economics is the dismal science, as Thomas Carlyle infamously said, reprising John Stuart Mill for defending the abolishment of slavery in the British Empire. But if being a “dismal science” includes respecting individual rights and standing up for early ideas of subjective, revealed, preferences – sign me up! Indeed, British economist Diane Coyle wisely pointed out that we should probably wear the charge as a badge of honor.

Non-economists, quite wrongly, attack economics for considering itself the “Queen of the Social Science”, firing up slurs, insults and contours: Economism, economic imperialism, heartless money-grabbers. Instead, I posit, one of our great contributions to mankind lies in clarity and, quoting Joseph Persky “an acute sensitivity to budget constraints and opportunity costs.”

Now, clarity requires one to be specific. To clearly define the terms of use, and refrain from the vague generality of unmeasurable and undefinable concepts so common among the subjects over whom economics is the queen. When economists do their best to be specific, they sometimes use terms that also have a colloquial meaning, seriously confusing the layman while remaining perfectly clear for those of us who “speak the language”. I realize the irony here, and therefore attempt my best to straighten out some of these things, giving the examples of 1) money and 2) investments.

An age-old way to see this mismatch is measuring the beliefs held by the vast majority of economists and the general public (Browsing the Chicago IGM surveys gives some examples of this). Bryan Caplan illustrates this very well in his 2006 book The Myth of the Rational Voter:

Noneconomists and economists appear to systematically disagree on an array of topics. The SAEE [“Survey of Americans and Economists on the Economy”] shows that they do. Economists appear to base their beliefs on logic and evidence. The SAEE rules out the competing theories that economists primarily rationalize their self-interest or political ideology. Economists appear to know more about economics than the public. (p. 83)

Harvard Professor Greg Mankiw lists some well-known positions where the beliefs of economists and laymen diverge significantly (rent control, tariffs, agricultural subsidies and minimum wages). The case I, Mankiw, Caplan and pretty much any economist would make is one of appeal to authority: if people who spent their lives studying something overwelmingly agree on the consequences of a certain position within their area of expertise (tariffs, minimum wage, subsidies etc) and in stark opposition to people who at best read a few newspapers now and again, you may wanna go with the learned folk. Just sayin’.

Caplan even humorously compared the ‘appeal to authority’ of other professions to economists:

In principle, experts could be mistaken instead of the public. But if mathematicians, logicians, or statisticians say the public is wrong, who would dream of “blaming the experts”? Economists get a lot less respect. (p. 53)

Money, Wealth, Income

The average public confusingly uses all of these terms interchangeably. A rich person has ‘money’, and being rich is either a reference to income or to wealth, or sometimes both – sometimes even in the same sentence. Economists, being specialists, should naturally have a more precise and clear meaning attached to these words. For us Income refers to a flow of purchasing power over a certain period (=wage, interest payments), whereas Wealth is a stock of assets or “fixed” purchasing power; my monthly salary is income whereas the ownership of my house is wealth (the confusion here may be attributable to the fact that prices of wealth – shares, house prices etc – can and often do change over short periods of time, and that people who specialize in trading assets can thereby create income for themselves).

‘Money’, which to the average public means either wealth or income, is to the economist simply the metric we use, the medium of exchange, the physical/digital object we pass forth and back in order to clear transactions; representing the unit of account, the thing in which we calculate money (=dollars). That little green-ish piece of paper we instantly think of as ‘money’. To illustrate the difference: As a poor student, I may currently have very little income and even negative wealth, but I still possess money with which I pay my rent and groceries. In the same way, Bill Gates with massive amounts of wealth can lack ‘money’, simply meaning that he would need to stop by the ATM.

Investment

A lot like money, the practice of calling everything an ‘investment’ is annoying to most economists: the misuse drives us nuts! We’re commonly told that some durable consumption good was an investment, simply because I use it often; I’ve had major disagreements friends over the investment or consumption status of a) cars, b) houses, c) clothes, and d) every other object under the sun. Much like ‘money’, ‘investment’ to the general public seem to mean anything that gives you some form of benefit or pleasure. Or it may more narrowly mean buying financial assets (stocks, shares, derivatives…). For economists, it means something much more specific. Investopedia brilliantly explains it: The definition has two components; first, it generates an income (or is hoped to appreciate in value); secondly, it is not consumed today but used to create wealth:

An investment is an asset or item that is purchased with the hope that it will generate income or will appreciate in the future. In an economic sense, an investment is the purchase of goods that are not consumed today but are used in the future to create wealth.

This definition clearly shows why clothes, yoga mats and cars are not investments; they are clearly consumption goods that, although giving us lots of joy and benefits, generates zero income, won’t appreciate and is gradually worn out (i.e. consumed). Almost as clearly, houses (bought to live in) aren’t investments (newsflash a decade after the financial crisis); they generate no income for the occupants (but lots of costs!) and deteriorates over time as they are consumed. The only confusing element here is the appreciation in value, which is an abnormal feature of the last say four decades: the general trend in history has been that housing prices move with price inflation, i.e. don’t lose value other than through deterioration. In fact, Adam Smith said the very same thing about housing as an investment:

A dwelling-house, as such, contributed nothing to the revenue of its inhabitant; and though it is no doubt extremely useful to him, it is as his cloaths and household furniture are useful to him, which however make a part of his expence, and not his revenue. (AS, Wealth of Nations, II.1.12)

Cars are even worse, depreciating significantly the minute you leave the parking lot of the dealership. Where the Investopedia definition above comes up short is for business investments; when my local bakery purchases a new oven, it passes the first criteria (generates incomes, in terms of bread I can sell), but not the second, since it is generally consumed today. Some other tricky example are cases where political interests attempt to capture the persuasive language of economists for their own purposes: that we need to invest in our future, either meaning non-fossil fuel energy production, health care or some form of publicly-funded education. It is much less clear that these are investments, since they seldom generate an income and are more like extremely durable consumption goods (if they do classify on some kind of societal level, they seem like very bad ones).

In summary, economists think of investments as something yielding monetary returns in one way or another. Either directly like interest paid on bonds or deposits (or dividends on stocks) or like companies transforming inputs into revenue-generating output. It is, however, clear that most things the public refer to as investments (cars, clothes, houses) are very far from the economists’ understanding.

Economists and the general public often don’t see eye-to-eye. But improving the communication between the two should hopefully allow them to – indeed, the clarity with which we do so is our claim to fame in the first place.

Revised version of blog post originally published in Nov 2016 on Life of an Econ Student as a reflection on Establishment-General Public Divide.

Nightcap

- Leaving Saigon Peter Gordon, Asian Review of Books

- On neoliberalism Chris Dillow, Stumbling and Mumbling

- Obama’s legacy has already been destroyed Andrew Sullivan, Daily Intelligencer

- Harmless or harassment? Conor Friedersdorf, the Atlantic

Lucas Freire: 2018 Novak Award winner

Edwin just alerted me to this announcement from the Acton Institute:

GRAND RAPIDS, Mich., May 23, 2018—In recognition of Professor Lucas G. Freire’s outstanding research in the fields of philosophy, religion, and economics in the ancient Near East, the Acton Institute will be awarding him the 2018 Novak Award.

Despite Michael Novak’s passing in February 2017, his memory will continue to be honored every year with the presentation of the Novak Award. This recognizes new outstanding research by scholars early in their academic careers who demonstrate outstanding intellectual merit in advancing understanding of the relationship between religion, the economy, and economic freedom. Recipients of the Novak Award make a formal presentation at an annual public forum known as the Calihan Lecture. The Novak Award comes with a $15,000 prize.

Lucas G. Freire is an assistant professor at Mackenzie Presbyterian University in São Paulo, Brazil, and a fellow at the university’s new Center for Economic Freedom. He is also a postdoctoral fellow at North-West University in Potchefstroom, South Africa. He received his PhD in politics from the University of Exeter. Previously, he also served as a research associate with the Kirby Laing Institute for Christian Ethics in Cambridge, UK.

Professor Freire has commented on political and economic issues drawing on Christian thinking in the Reformed tradition. He has published on political theory and philosophy in journals such as Philosophia Reformata and Acta Academica. His current research focuses on the connection between religion, politics and economics in the ancient Near East and the biblical world. He lives in São Paulo with his wife and two children.

Congratulations Lucas!

Here are his posts at NOL so far. Now that he’s got a bit more money in his pocket, perhaps he will have some time to spare for blogging…

The State in education – Part I: A History

In Beyond Good and Evil, written after breaking with composer Richard Wagner and subsequently rejecting hyper-nationalism, Friedrich Nietzsche proposed the existence of a group of people who cannot abide to see others successful or happy. Appropriately, he dubbed these people and their attitude “ressentiment,” or “resentment” in French. His profile of the resentful is most unkind, bordering on the snobbish – though Nietzsche had very little personal cause to feel superior (he was part of the minor nobility but always insisted that, due to his father’s premature death and his mother’s lack of connections, his legal rank was never of much benefit to him). Insanely proud of his classical education and remarkable, even for that time, fluency in Ancient Greek and Latin, the philosopher latched onto these languages as symbolic variables in his descriptions of society and its woes.

Much like the French philosopher Simone de Beauvoir who, a century later, attempted to prove that history was made by socio-cultural gender dynamics (Le deuxième sexe), Nietzsche proposed that all of (European) history since the fall of the Roman Empire was a battle between the cosmopolitan, classically-educated aristocracy and the technician, parochial lower classes. Unlike de Beauvoir who saw the world as oppressor-oppressed, the German believed that the lower orders, motivated by jealousy and feelings of exclusion, tried to pull their superiors down, creating a peculiar situation in which those who believed themselves the oppressed engaged in oppressive behavior.

As evidence of his theory, Nietzsche suggested in The Genealogy of Morals that the Protestant Reformation was the ultimate achievement of the resentful classes; functionaries, unable to understand the Latin of the Roman liturgy, read the writings of the ancient and medieval philosophers, or participate meaningfully in the conversations and society of the Renaissance, responded by turning the Church into the personification of all they hated – not unlike a voodoo doll – and then ousted it from their lives and countries. At least, this is what Nietzsche thought had occurred, adding that the cloddish nationalism that he had rejected would not have been possible without first banishing the Catholic Church and the refinement it introduced through fostering Latin, Greek, and Classical literature and philosophy.

On the practical plane, Nietzsche’s primary concern, post-Wagner, was the advent of Prussian hegemony and the loss of autonomy among the German member states. Before his friendship with Wagner, Nietzsche gave a lecture series on education which he intended to collect and publish as a book. The book never materialized [until 2016, when the Paul Reitter compiled the notes and lecture transcripts into book form under the title Anti-Education], but the philosopher did write a preface that he gifted to Cosima Wagner under the title “Five Prefaces to Five Unwritten Books,” which helped precipitate the quarrel since Nietzsche signaled clearly that he rejected the Wagnerian philosophy of the innate nobility of the (German) savage.

Much of Anti-Education is harsh and unyielding, moreover because there is much in it that is true. In it, one can see the early kernels of Nietzsche’s identification of ressentiment and the genesis of ideas concerning individuality and nobility that he returned to later in life. There is also much that is applicable today.

Nietzsche asked,

Why does the state need such a surplus of educational institutions and teachers? Why promote popular enlightenment on such scale? Because the genuine German spirit [that of the Renaissance princes] is so hated – because they fear the aristocratic nature of true education and culture – because they are determined to drive the few that are great into self-imposed exile, so that a pretension of culture can be implanted and cultivated in the many – because they want to avoid the hard and rigorous discipline of the great leader, and convince the masses that they can find the guiding path for themselves … under the guiding star of the state! Now that is something new: the state as the guiding star of culture!

Nietzsche wrote / spoke this on the takeover by the state of the education system, also known as the Prussian public school system, which “reformer” Horace Mann promptly imported to the United States. The false promise of public education, as Nietzsche saw it, was that state schools claimed the laurels and legitimacy of private gymnasia through deceit – speaking to a university audience, he expected everyone to know that pre-state control, there were two types of secondary schools: gymnasium, where the student received a classical education and prepared to enter university, and realschule, where the student learned the three Rs, along with some science, and entered the workforce immediately after graduation. Nietzsche claimed that while the gymnasium curriculum needed a significant overhaul, the only products of the realschule were conformity, obedience, and an inflated sense of achievement. Hence, he believed, when the government took over the education system, officials chose to model the public school on the old realschule, while claiming that graduates had the knowledge and skills of the gymnasium.

It is important to note at this juncture that Nietzsche bore a very visceral hatred of the Prussians in general and of Otto von Bismarck in particular. Viewing the former as unintelligent clods whose threat lay in their stupidity, the philosopher deemed the latter and his eponymous Bismarckian welfare state a greater threat to personal freedom. From 1888 until his nervous breakdown and descent into madness in 1899, Nietzsche called for the trial of Bismarck for treason, along with the removal of Kaiser Wilhelm II, in a sequence of letters and essays which his sister and executors suppressed, both to accommodate their own agendas and to avoid the attention of the censors.

The treason of Bismarck lay in his creation of a nation whose people were unwittingly dependent on the state. The state provided education during infancy and a pension in old age. As Nietzsche correctly saw, when the state controls the beginning of the pipeline and the end, everyone is in its employ. As he also foretold, the situation would end in violence (for Germany specifically; hence his interest in preempting war by removing its figurehead king) and heartbreak for those who placed their faith in the anti-individualistic state.

At a very fundamental level, Nietzsche believed that the public school system, with is inadequate education and contempt for classical learning and languages, was a conspiracy designed to drive a wedge among the social classes, enabling the state to increase control in the ensuing vacuum. The other aspect he identified was the use of public opinion to strip the individual of drive or thirst for a better life through a mixture of flattery and subversion of ambition. The outcome would be war and resentment, he predicted, for any country foolish enough to have faith in the Prussian system. Next week, we will examine whether Nietzsche’s predictions have come true in modern American education.

Nightcap

- Siege of Acre a monstrous blot on the Crusades Sean McGlynn, Spectator

- The origins of globalization Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

- Racism and the pure, white elephant Ross Bullen, Public Domain Review

- Against hijacking utopia Scott Alexander, Slate Star Codex