- Conservatives in academia Fabio Rojas, orgtheory

- Cuba’s lack of literature Nick Caistor, Times Literary Supplement

- The Democratic Party’s identity crisis William Voegeli, Claremont Review of Books

- How Fortress Europe was built Kenan Malik, Guardian

Why protect speech?

The U.S. Supreme Court has extended more protection for speech than other major courts that adjudicate rights, such as the European Court of Human of Rights. Nonetheless, the Supreme Court is frequently wrong about why speech deserves constitutional protection. That error has undermined the First Amendment that the Court purports to protect. Continue reading

Nightcap

- Canada’s Dark Side Susan Neylan, Origins

- The ethics of looted art Ian Johnson, NY Times

- Van Gogh and Japan Alastair Sooke, BBC

- How Chinese students exercise free speech abroad Fran Martin, Economist

The TSA Wins

Since 2012 I have been a semi-frequent flyer making about five cross continental round trip flights a year, plus several shorter flights within the Pacific coast. Between now and then I would make it a point to ‘opt out’ of the standard TSA procedure and receive the pat down. I did it for a variety of reasons. For one, don’t like being exposed to radiation and don’t trust the government on the issue.

More than that though, I wanted to resist and encourage my fellow citizens to resist, however small, the security theater the government has us go through in exchange for our freedom to travel. I would not encourage people to resist the police or any armed agent of the state, but by opting out I was taking a stand against government and hoped others would join me.

In five plus years, no one did. The only people I ever had join me in the opt out process was ‘randomly selected’ individals, often Muslims or mis-identified Sikhs. I never saw someone else voluntarily opt out. In retrospect, I suspect noone else saw my actions as a form of protest.

When I took a flight earlier today I went through the standard procedure.* My will to resist, at least in this form, has gone away. In the coming year the TSA rules will become stricter as real ID is finally implemented. I like to think this will lead to popular opposition, but I wouldn’t wager on it. As a nation we’ve given up on asserting our freedom to travel with minimal intrusion.

When I arrived at my final destination I found the below containers blocking me from the entrance. To leave the airport I had to get checked one last time. They don’t seem to be scanners, but when you enter them you are held up for ten or so seconds before being let free. Are they just trying to see what we will put up with before unveiling the next wave of security theater antics?

Thoughts? Have a story about your flying experience(s) to share? Post in the comments below.

___

*Funnily enough I ended up being “randomly” choosen to have my luggage physically inspected anyway.

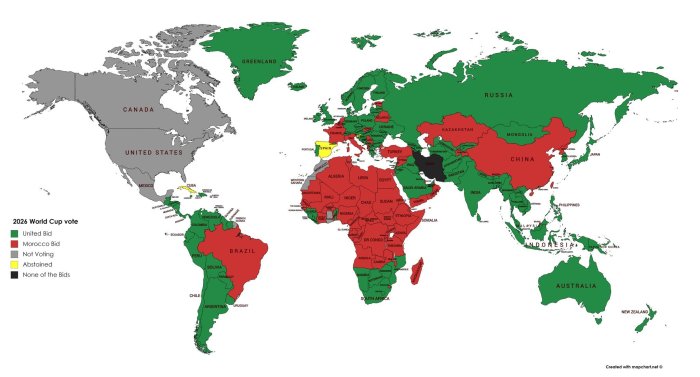

Eye Candy: 2026 World Cup votes, by country

My only question is why did 3 countries that could easily (and have, in the past) host the World Cup on their own gang together? Mexico, Canada, and the United States are wealthy countries. Why gang up?

My guess is that wealthier countries are going to have to do a lot more cooperating if they want to host world-level events from now on, due to the fact that the selection process for these types of events has become democratized. Economist Branko Milanovic has a thoughtful piece on FIFA (the governing body for world-level soccer events) and corruption that ties in to all of this.

Nightcap

- The Market Police (Neoliberalism) JW Mason, Boston Review

- Libertarians should stop focusing on rent capture Henry Farrell, Cato Unbound

- Libertarians should *really* stop focusing on rent capture Mike Konczal, RortyBomb

- Nationalism is an essential bulwark against imperialism Sumantra Maitra, Claremont Review of Books

Meat-y Twitter Spat: Choice, Vegetarianism and Caste in India

A couple of weeks ago I was in the middle of submission week (when am I not?). Obviously, an otherwise mundane tweet piqued my supremely scattered mind’s ever-shifting interest. The series of tweets argued that unless one had actually tasted meat, she was not a vegetarian by choice but a vegetarian by caste. It seemed a silly proposition to me. It seemed as silly as claiming that unless one has lived off meat for a year, she is a meat eater by caste, not by choice. Urban Indian Vegetarians (towards whom the tweets were directed) do not live in an either-or world; their individual judgments, howsoever influenced by the household they were born in, do not flicker between ‘my caste dictates I must not eat meat’ and ‘my taste buds like/dislike meat’. Between the orthodox social and the over simplified gustatory lies an ocean of personal judgments.

In response to my tweets, I was told I was missing the context, that upper caste Hindus were vegetarians because of a puranical belief in the impurity of meat. Sure, I said. If I look down upon a meat eater from some ill-founded moral high ground, I am nothing but a bigot who deserves to be called out. If, however, I chose to stick to my greens without ever experiencing the delight that is a chicken butter masala but have no qualms with you eating pork, what seems to be the problem?

Like a number of judgments we make (moral or otherwise), food preferences are also influenced by the environment we grow up in. But does mean that a child’s food preferences are motivated by the same reasons as her ancestors? People from coastal areas prefer seafood. While their ancestors might have preferred a healthy diet of fish over okra for any number of reasons (Religion? Caste? Sheer affordability?), could the children, as individuals capable of making free-standing judgments exposed to very different environments, take a liking for fish for completely different reasons, unaware and independent of their ancestors’?

Can contextualizing discount generalisations? We have consensus on contextualizing not working out well for Trump and his feelings for Mexicans how much ever the Mexican drug lords might have contributed to the law and order situation in America. Mexicans do not become rapists because of their identity. Muslims do not turn into terrorists because of their identity. The logic of it seems pretty clear. Can we then derive a principle from this consensus? Context does not justify identity based generalisations. Casteism is a very real problem in India. But no matter what the context, you are wrong if you think you have the qualification to approve of someone’s personal choices. Calls for contextualization seem like an attempt to sweep social-identity-based generalisations under the rug – the very thing that brought about casteism in the first place.

Identity based stratification is a very real problem across the world. The trick is not to demonize the identity but call out the dehumanizing ideology that is functioning in that group. My Jewish friends can choose to go Kosher for any number of reasons, as long as they don’t demonize the rest of us. My white friends are not racists if they are attracted towards other white people. And my gay friend need not sleep with a person of the opposite gender to prove that his choice of life partner is not influenced by his lesbian moms. Choice, by definition, means having an alternative option. Not exercising all the alternatives is a prerogative and it does not take away from the legitimacy of your choice.

But this forms only a minuscule percentage of the replies I got to my tweets. Most just called me an Upper Caste {insert abuse}. I soon realized this was not a debate on what prompts vegetarianism in India. This was a statement. And I, by virtue of my social identity, was not eligible to comment on it. Makes me wonder – the politics of identity is like an hourglass. One side will always lose as long as you continue to use something as tricky as sand as a parameter. I will turn more academic in my series on Arendt where I evaluate her take on identity (because I was also told that Arendt would want us to contextualize and I humbly disagree). I will discuss Arendt on collective identity, her idea of what it meant to separate ‘the political’ from ‘the social’, and finally, identity politics.

P.S: Stepping out of your echo chamber is really bad for your twitter notification bar. Excellent for the follower count though.

Nightcap

- Icelandic fiction: a family affair Fríða Ísberg, Times Literary Supplement

- Icelandic sagas of the middle ages Barry Stocker, NOL

- Identity politics and patchwork Xenogoth

- Keeping it cool: worshipping the goddess Shitala Amrapali Saha, Coldnoon

A note on India’s performance at the recent SCO Summit

The Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) Summit, from June 9-10, went largely as expected. The Indian Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, met the Chinese President, Xi Jinping, on the sidelines of the summit. New Delhi’s proposal to have an informal summit, in India in 2019, on the lines of the Wuhan Summit (held in April 2018) was accepted by the Chinese. Agreements were also signed between both countries with regard to sharing hydrological data on the Brahmaputra River, and export of non-Basmati varieties of rice from India. Another issue, which was discussed during the Modi-Xi meeting, was the joint capacity development project in Afghanistan, which was first proposed during the Wuhan Summit.

Commenting on his meeting with the Chinese President, Modi tweeted:

Met this year’s SCO host, President Xi Jinping this evening. We had detailed discussions on bilateral and global issues. Our talks will add further vigour to the India-China friendship.

Modi’s meetings with leaders of other member countries

The Indian PM met other leaders of member countries, including the presidents of Tajikistan and Uzbekistan. While there was no formal meeting with the Pakistani President Mamnoon Hussain, Modi did shake hands with Hussain and exchange pleasantries. Interestingly, Chinese President Xi Jinping, during his address, had spoken about the presence of both leaders, as well as entry of both countries into the SCO. Said the Chinese President: Continue reading

The Politics of the Incredibles (minimal spoilers)

I saw an early release of the Incredibles 2 last night. I wasn’t expecting too much given Pixar’s history with sequel. Finding Dorothy, Monsters University and the Cars sequels were okay, but below average for Pixar. I am happy to report that the Incredibles 2 was a pleasant exception. Not only did the film re-capture the magic of the original, it made a point that many readers and fellow Notewriters should appreciate: legality doesn’t equal right.

The film starts off directly after the events of the first film. The titular Incredibles family fights off the Underminer, a mining themed super villain. Instead of getting praised for their actions though, they get arrested. Superheroes are still illegal. The events of the past film haven’t changed that. One of the characters wisely remarks, “Politicians don’t understand why someone would do the right thing for its own sake. They’re scared of the idea.”

The family is let go, but they’re at a low point. Their home has been destroyed. They’re unemployed and broke. They’re gifted with super powers, but they live in a world where they can’t legally use them. That’s when a businessman approaches them and asks – why not use their super powers? The businessman proposes that the family continue to use their powers illegally, and convince the government to change the law after the public has been shown how useful superheroes are. This leads to a funny exchange where the characters argue about how they’re being asked to be illegal in order to become legal.

I won’t spoil the remainder of the film, but I love the businessman character’s early scenes. It’s refreshing to see a corporate character, and his disregard for legislated morality, portrayed in a positive light. Tony Stark/Iron Man starts off this way in the early MCU films, but makes a u-turn by Captain America: Civil War. This new character, for better or worse, stands by his beliefs.

The tension between legislation and morality isn’t a new theme for Pixar. The idea of breaking the rules to do what’s right was a central feature of Monsters University as well. It’s a lesson I think many children, and their parents, could benefit to learn. Legislation isn’t morality.

I give the film a solid 9/10. It’s around Wall-E or Up levels of quality. It’s easily one of the funniest Pixar films in a while. The animated short before the film is, as standard for Pixar, a tear jerker. Bring some tissues.

Thoughts? Opinions? Post in the comments.

Nightcap

- An election day parable Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Unrevolutionary bastardy Hannah Farber, The Junto

- Voting for a lesser evil Ilya Somin, Volokh Conspiracy

- Max Weber’s ‘spirit’ of capitalism Peter Ghosh, Aeon

The minimum wage induced spur of technological innovation ought not be praised

In a recent article at Reason.com, Christian Britschgi argues that “Government-mandated price hikes do a lot of things. Spurring technological innovation is not one of them”. This is in response to the self-serve kiosks in fast-food restaurants that seem to have appeared everywhere following increases in the minimum wage.

In essence, his argument is that minimum wages do not induce technological innovation. That is an empirical question. I am willing to consider that this is not the most significant of adjustment margins to large changes in the minimum wage. The work of Andrew Seltzer on the minimum wage during the Great Depression in the United States suggests that at the very least it ought not be discarded. Britschgi does not provide such evidence, he merely cites anecdotal pieces of support. Not that anecdotes are bad, but those that are cited come from the kiosk industry – hardly a neutral source.

That being said, this is not what makes me contentious towards the article. It is the implicit presupposition contained within: that technological innovation is good.

No, technological innovation is not necessarily good. Firms can use two inputs (capital and labor) and, given prices and return rates, there is an optimal allocation of both. If you change the relative prices of each, you change the optimal allocation. However, absent the regulated price change, the production decisions are optimal. With the regulated price change, the production decisions are the best available under the constraint of working within a suboptimal framework. Thus, you are inducing a rate of technological innovation which is too fast relative to the optimal rate.

You may think that this is a little luddite of me to say, but it is not. It is a complement to the idea that there are “skill-biased” technological change (See notably this article of Daron Acemoglu and this one by Bekman et al.). If the regulated wage change affects a particular segment of the labor (say the unskilled portions – e.g. those working in fast food restaurants), it changes the optimal quantity of that labor to hire. Sure, it bumps up demand for certain types of workers (e.g. machine designers and repairmen) but it is still suboptimal. One should not presuppose that ipso facto, technological change is good. What matters is the “optimal” rate of change. In this case, one can argue that the minimum wage (if pushed up too high) induces a rate of technological change that is too fast and will act in disfavor of unskilled workers.

As such, yes, the artificial spurring of technological change should not be deemed desirable!

The State in education – Part III: Institutionalization of learning

In The State in education – Part II: social warfare, we looked at the promise of state-sponsored education and its failure, both socially and as a purveyor of knowledge. The next step is to examine the university, especially since higher education is deeply linked to modern society and because the public school system purports to prepare its students for college.

First, though, there should be a little history on higher education in the West for context since Nietzsche assumed that everyone knew it when he made his remarks in Anti-Education. The university as an abstract concept dates to Aristotle and his Peripatetic School. Following his stint as Alexander the Great’s tutor, Aristotle returned to Athens and opened a school at the Lyceum (Λύκειον) Temple. There, for a fee, he provided the young men of Athens with the same education he had given Alexander. On a side note, this is also a beautiful example of capitalist equality: a royal education was available to all in a mutually beneficial exchange; Aristotle made a living, and the Athenians received brains.

The Lyceum was not a degree granting institution, and only by a man’s knowledge of philosophy, history, literature, language, and debating skills could one tell that he had studied at the Lyceum. A cultural premium on bragging rights soon followed, though, and famous philosophers opening immensely popular schools became de rigueur. By the rise of Roman imperium in the Mediterranean around 250 BC, Hellenic writers included their intellectual pedigrees, i.e. all the famous teachers they had studied with, in their introductions as a credibility passport. The Romans were avid Hellenophiles and adopted everything Greek unilaterally, including the concept of the lyceum-university.

Following the Dark Ages (and not getting into the debate over whether the time was truly dark or not), the modern university emerged in 1088, with the Università di Bologna. It was more of a club than an institution; as Robert S. Rait, mid-20th century medieval historian, remarked in his book Life in the Medieval University, the original meaning of “university” was “association” and it was not used exclusively for education. The main attractions of the university as a concept were it was secular and provided access to books, which were prohibitively expensive at the individual level before the printing press. A bisection of the profiles of Swedish foreign students enrolled at the Leipzig University between 1409 and 1520 shows that the average male student was destined either for the clergy on a prelate track or was of noble extraction. As the article points out, none of the students who later joined the knighthood formally graduated, but the student body is indicative of the associative nature of the university.

The example of Lady Elena Lucrezia Cornaro Piscopia, the first woman to receive a doctoral degree, awarded by the University of Padua in 1678, illuminates the difference between “university” at its original intent and the institutional concept. Cornaro wrote her thesis independently, taking the doctoral exams and defending her work when she and her advisor felt she was ready. No enrollment or attendance at classes was necessary, deemed so unnecessary that she skipped both the bachelor and masters stages. What mattered was that a candidate knew the subject, not the method of acquisition. Even by the mid-19th century, this particular path remained open to remarkable scholars, such as Nietzsche since Leipzig University awarded him his doctorate on the basis of his published articles, rather than a dissertation and defense.

Education’s institutionalization, i.e. the focus shifting more from knowledge to “the experience,” accompanied a broader societal shift. Nietzsche noted in Beyond Good and Evil that humans have an inherent need for boundaries and systemic education played a very prominent role in contemporary man’s processing of that need:

There is an instinct for rank which, more than anything else, is a sign of a high rank; there is a delight in the nuances of reverence that allows us to infer noble origins and habits. The refinement, graciousness, and height of a soul is dangerously tested when something of the first rank passes by without being as yet protected by the shudders of authority against obtrusive efforts and ineptitudes – something that goes its way unmarked, undiscovered, tempting, perhaps capriciously concealed and disguised, like a living touchstone. […] Much is gained once the feeling has finally been cultivated in the masses (among the shallow and in the high-speed intestines of every kind) that they are not to touch everything; that there are holy experiences before which they have to take off their shoes and keep away their unclean hands – this is almost their greatest advance toward humanity. Conversely, perhaps there is nothing about so-called educated people and believers in “modern ideas” that is as nauseous as their lack of modesty and the comfortable insolence in their eyes and hands with which they touch, lick, and finger everything [….] (“What is Noble,” 263)

The idea the philosopher pursued was the notion that university attendance conveyed the future right to “touch, lick, and finger everything,” a very graphic and curmudgeonly way of saying that a certain demographic assumed unjustified airs.

Given that in Anti-Education, Nietzsche lamented the fragmentation of learning into individual disciplines, causing students to lose a sense of the wholeness, the universality of knowledge, what he hated in the nouveau educated, if we will, was the rise of the pseudo-expert – a person whose knowledge was confined to the bounds of a fixed field but was revered as omniscient. The applicability of Socrates’ dialogue with Meno – the one where teacher and student discuss human tendency to lose sight of the whole in pursuit of individual strands – to the situation was unmistakable, something which Nietzsche, a passionate classicist, noticed. The loss of the Renaissance learning model, the trivium and the quadrivium, both of which emphasize an integrated learning matrix, carried with it a belief that excessive specialization was positive; it was a very perverse version of “jack of all trades, master of none.” As Nietzsche bemoaned, the newly-educated desired masters without realizing that all they obtained were jacks. In this, he foreshadowed the disaster of the Versailles Treaty in 1919 and the consequences of Woodrow Wilson’s unwholesome belief in “experts.”

The philosopher squarely blamed the model of the realschule, with its clear-cut subjects and predictable exams, for the breakdown between knowledge acquisition and learning. While he excoriated the Prussian government for basing all public education on the realschule, he admitted that the fragmentation of the university into departments and majors occurred at the will of the people. This was a “chicken or the egg” situation: Was the state or broader society responsible for university learning becoming more like high school? This was not a question Nietzsche was interested in answering since he cared more about consequences. However, he did believe that the root was admitting realschule people to university in the first place. Since such a hypothesis is very applicable today, we will examine it in the contemporary American context next.

Nightcap

- The underbelly of state capacity Bryan Caplan, EconLog

- Realities and uncertainties of American Empire AG Hopkins, Defense-In-Depth

- Emancipation and representation in 1848 Senegal Jenna Nigro, Age of Revolutions

- The Koreas are moving ahead Ramon Pacheco Pardo, the Hill

A note on the three Californias and arbitrary borders

As many of you may know, there is a proposal to split up California into three parts: north, south and ‘ye olde’ California. This proposal is idiotic on several fronts. For starters the best university in LA, the University of Southern California, would find itself in ye olde California. Meanwhile my university, UC Riverside, would overnight become USC Riverside. Now, I wouldn’t be against the Trojan football team relocating to Riverside, especially since Riverside doesn’t have a team of it’s own. However the proposed split would cut off the Inland Empire and Orange County from Los Angeles county.

This despite the fact that the greater LA area is composed of LA-Ventura-Riverside-San Bernardino-Orange counties. These counties are deeply interwoven with one another, and dividing them is bizarre. Imagine the poor “Los Angeles Angels at Anaheim”. What horrendous name will they have to take on next? The “San Diego Angeles at Anaheim”?

Beyond it’s idiocy the proposal makes a larger point: government borders are, for the most part, arbitrary and plain stupid. The proposal to split up California ignores the regions socio-cultural ties to one another, but there are countless other examples of senseless borders.

For example, who was the bright guy that decided to split up Kansas City between Missouri and Kansas? And let’s not even get started on the absurd borders of the old world.

Thoughts? Disagreements? Post in the comments.