- Armistice Day John Quiggin, Crooked Timber

- The Second Hundred Years’ War Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

- When the World Tried to Outlaw War Stephen Wertheim, the Nation

- Blood, Oil, and Citizenship Kenan Malik, Guardian

The Negative Capability of a Good Legislator

In a former post, we had explored the idea of considering the law as an abstract machine which provides its users with information about the correct expectancies about human conduct that, if fulfilled, would contribute to the social system inner stability (here). The specific characteristic of the law working as an abstract machine resides in its capability of dealing with an amount of information more complex than human minds. This thesis had been previously stated by Friedrich Hayek in his late work titled “Law, Legislation and Liberty”, aimed to provide the foundations to a proposal of an constitutional reform that would assure the separation of the law from politics -not in the sense of depriving politics from the rule of law, but to protect law from the interference of politics.

Paradoxically, the said opus had many unintended outcomes that surpassed the author’s foresight. One of them was the coinage of the notion of “Spontaneous Order”, which Hayek himself regretted about, because of the misleading sense of the word “spontaneous”. At the foreword of the third volume of the cited “Law, Legislation and Liberty”, he explained why he would prefer to use of the term of “Abstract Order”. Notwithstanding its creator’s allegations, the label of “Spontaneous Order” gained autonomy from him in the realm of the ideas (for example, here).

Why better “abstract order” than “spontaneous”? Because while no “concrete order” might be spontaneous, we could nevertheless find normative systems created by human decision, besides the spontaneous ones (see “Law, Legislation and Liberty”, Chapter V). Moreover, we do not see spontaneous orders whose rules fail to provide stability to the system, because of “evolutionary matters”: such orders could not endure the test of time. Nevertheless, for the same reason, we could imagine a spontaneous order whose rules of conduct became obsolete due to a change in the environment and, thus, fails to enable the social system with the needed stability.

Spontaneity is, thus, not the central characteristic of the law as a complex order. What delimits law from a “concrete order” is the level of abstraction. An alternative name given by Hayek to designate the concrete orders was the Greek term “taxis”, a disposition of soldiers for battle commanded by the single voice of the general. Concrete orders could be fully understood by the human mind and that is why they are regarded as “simple phenomena”: the whole outcome of their rules could be predicted by a system of equations simpler than the human mind.

Notwithstanding a single legislator could sanction a complete set of rules to be followed by the members of a given society, the inner system of decision making of those individuals are more abstract that the said set of rules and, thus, the human interactions will always result in some subset of unintended consequences.

These unintended consequences should not necessarily be regarded as deviations from the social order, but indeed as factors of stabilisation -and, thus, all abstract orders are, in some sense, still spontaneous. These characteristics of the law as a complex order concern on the information about the final configuration of a society given a certain institutional frame: we can establish the whole set of institutions but never fully predict its final outcome. At this stage, we reach what Hayek called in The Sensory Order “an absolute limit to knowledge”.

We now see that the legislator could sanction a complete system of rules -a system that provides solutions for every possible concrete controversy between at least two contenders-, but he is unable to be aware of the full set of consequences of that set of rules. We might ascertain, then, that being enabled with a “negative capability” to anticipate the outcome of the law as a complex phenomenon is a quality to be demanded to a good legislator.

By this “negative capability” we want to designate some understanding of the human nature that allows to anticipate the impact of a given norm among the human interactions. For example, simple statements about human nature such as “people respond to incentives”, or “all powers tend to be abusive”. These notions that are not theoretical but incompletely explained assumptions about human nature are well known in the arts and literature and constitute the undertow of the main narratives that remain mostly inarticulate.

Precisely, as Hayek stated, every abstract order rests upon a series of inarticulate rules, some of which might be discovered and later articulated by the judges, while other rules would remain inarticulate despite being elements of the normative system.

However, we praise Negative Capability as a virtue to be cultivated by the legislator, not by the judge. The function of the judge is to decide about the actual content of the law when applied to a particular case. It is the legislator the one who should foresee the influence to be exerted by the law upon a general pattern of human behaviour.

Notwithstanding Negative Capability could be dismissed in order of not being a scientific concept, this negative attribute is one of its main virtues: it means lack of ideology, in the sense given to that term by Kenneth Minogue. While an ideological political discourse reassures itself in a notion of scientific truth, at least a legislator inspired by common and humble ideas about human nature would be free from that “pretence of knowledge”.

Afternoon Tea: “Independent Indians and the U.S.-Mexican War”

This cross-border conversation had a broad and tragic context. In the early 1830s, following what for most had been nearly two generations of imperfect peace, Comanches, Kiowas, Navajos, and several different tribes of Apaches dramatically increased their attacks upon northern Mexican settlements. While contexts and motivations varied widely, most of the escalating violence reflected Mexico’s declining military and diplomatic capabilities, as well as burgeoning markets for stolen livestock and captives. Indian men raided Mexican ranches, haciendas, and towns, killing or capturing the people they found there, and stealing or destroying animals and other property. When able, Mexicans responded by attacking their enemies with comparable cruelty and avarice. Raids expanded, breeding reprisals and deepening enmities, until the searing violence touched all or parts of nine states.

This is from Brian DeLay, a historian at Cal-Berkeley. Here is a link.

Legal Immigration Into the United States (Part 18): Reforms I Would Favor

Now, here is what I, personally, a US citizen and an appreciative immigrant, as well as a small government conservative, would like to see happen: As I pointed out before, most liberals and quite a few conservatives perceive allowing all immigration as a sort of altruistic gesture. That includes those who do not overtly call for open borders but whose concrete proposals (“Abolish ICE.”) would result in a soft state that would provide the equivalent of open borders. As far as I can tell – with the major exception of Tabarrok, discussed above – many pure libertarians whisper that they are all for open borders, but they only whisper it. I speculate that they are forced to take this principled but unreasonable position to avoid having to defend the nation-state as a necessary institutional arrangement to control immigration. Frankly, I wish they would come out of the closet and I hope this essay will shame some into doing so.

The most urgent thing to my mind is to separate conceptually and bureaucratically with the utmost vigor, immigration intended to benefit us, American citizens and lawfully admitted immigrants, and beyond us, to promote a version of the American polity close to the Founders’ vision, on the one hand, from immigration intended to help someone else, or something else, on the other. The US can afford both but the amalgam of the two leads to bad policies. (See, for example the story “The Refugee Detectives: Inside Germany’s High-Stake Operation to Sort People Fleeing Death…” by Graeme Wood in The Atlantic, April 2018.)

Next, I think conservatives should favor, for now, an upper numerical limit to immigration, one pegged perhaps to the growth of our domestic population. Though my heart is not in it, it seems to me that this is a prudent recommendation in view of the threatening prospect of a Democratic one-party governance.

The first category of immigrants would be admitted on some sort of merit basis, as I said, perhaps a version of the system I discuss above. The second category would include all refugees and asylum seekers, and, to a limited extent, their relatives. Given a strictly altruistic intent in accepting such people, Congress and the President jointly would be in a better position than they are today to apply any strictures at all, including philosophical and even religious tests of compatibility with central features of American legal and philosophical tradition – if any. (Of course, in spite of the courts’ interventions in the matter, I have not found the part of the Constitution that forbids the Federal Government from barring anyone it wants, including on religious grounds. Rational arguments can be made against such decisions but they are not anchored in the Constitution, I believe. (See constitutional lawyers David B. Rivkin and Lee A. Casey’s analysis: “The Judicial ‘Resistance’ is Futile” in the Wall Street Journal of 2/7/18.)

I think thus both that we could admit many more people seeking shelter from war and other catastrophes than we do, and that we should vet them extensively and deeply. We could also rehabilitate the notion of provisional admission. Many of the large number of current Syrian refugees would not doubt like to go home if it were possible. Such refugees could be given, say, a five-year renewable visa. As I pointed out above, some beliefs system are but little compatible with peaceful assimilation into American society. This can be said aloud without proffering superfluous insults toward any group. National hypocrisy does not make sense because it rarely fools anyone. In general, I think all American society has been too shy in this connection, too submissive to political correctness. So, think of this example: French constitutions, most of the fifteen of them anyway, proclaim the primacy of something called “the general interest,” a wide open door to authoritarian collectivism if there ever was one. There is no reason to not query French would-be immigrants on this account. I would gladly take points off for answers expressing a submissiveness to this viewpoint. (Yes, I am one of those who suspect that the French Revolution is one of the mothers of democracy but also, of Communism and of Fascism.)

Similarly Muslim religious authorities as well as would-be Muslim immigrants could be challenged like this: Just tell us publicly if Islamic dogma welcomes separation of religion and government. State, also in public, loudly and clearly that apostasy does not deserve death, that it deserves no punishment at all. Admission decisions would be a function of the answers given. Sure, people would be coached and many would cheat but, they would be on record. The most sincere would not accept going on record against their doctrine. Sorry to be so cynical but I don’t fear the least sincere!

The underlying reasoning for such policies of exclusion is this: First, I repeat that there is no ethical system that obligates American society to commit suicide, fast or slowly; second, probabilistic calculations of danger and of usefulness both are the only practicable ones in the matter of admitting different groups and categories. (I don’t avoid jumping from planes with a parachute because those who do die every time they try but because they die more often than those who don’t.) Based on recent experience (twenty years+), Muslims are more likely to commit terrorist acts than Lutherans. (It’s also true that there is a very low probability for both groups.) Based on common sense and the news, most Mexicans must have acquired a high tolerance for political corruption. Based on longer experience, many Western Europeans have extensive and expensive expectations regarding the availability of tax supported welfare benefits. Based – perhaps- on one thousand years of observation, the Chinese tend to favor collective discipline over individual rights more than Americans do. (See my: “Muslim Refugees in perspective.”)

Pronouncing aloud these probabilistic statements does not shut off the possibility of ignoring them because immigrants from the same groups bring with them many improvements to American society, of course. I could easily allow a handful of well chosen French chefs to come in despite of their deep belief in the existence of a common public interest. I even have a list ready. Admitting facts is not the same as making decisions. I can also imagine a permanent invitation to anyone to challenge publicly such generalizations. It would have at least the merit of clearing the air.

Last and very importantly: Invalidating the generalizations I make above, to an unknown extent, is the likelihood that immigrants are not a true sample of their population of origin: Chinese immigrants may tend to have an anarchist streak; that may be the very reason they want to live in the US. Mexicans may seek to move to the US precisely to flee corruption for which they have a low tolerance, etc. The French individuals wishing to come to the US may be trying to escape the shadow of authoritarianism they perceive in French political thought, etc.

[Editor’s note: in case you missed it, here is Part 17]

Books I’ve been reading (and elections I’ve been watching)

The elections were pretty decent overall. The GOP actually picked up some seats in the Senate, the Democrats picked up some seats in the House. It was a draw, and now Trump is weaker than he was in 2016 and so are the Democrats. It’s a win-win for libertarians.

Speaking of libertarians, we have a political party here in the States, and it didn’t do too bad in the elections. It looks as if the Libertarian Party has started to run candidates in districts where a representative usually goes unchallenged. So, in heavily Democratic areas like urban Dallas or suburban Denver, or in heavily Republican areas like Wyoming, Libertarians have begun running legitimate campaigns. Jennifer Nakerud won 4% of the vote in suburban Denver, and Shawn Jones got nearly 9% of the vote in urban Dallas. In West Virginia, Rusty Hollen took 4% of the vote in the Senate race. Gary Johnson didn’t do too bad, either, finishing with almost 15% of the vote in New Mexico. He was running for Senate, and he was a very successful governor there, so his losing success was somewhat assured, but still, it’s encouraging. Also encouraging is the re-election of Clint Bolick, a libertarian judge in Arizona (Damon Root reports on Bolick’s victory at Reason, here).

I’ve plowed through a bunch of books recently: Sinclair Lewis’ Main Street (1920), Francis Spufford’s Red Plenty (2010), Nicolai Gogol’s Dead Souls (1842), the Three-Body Problem trilogy (2014-2016), and Prador Moon (2006), the first book in a long, 15-part science fiction series. They’ve all been richly rewarding, and I’ll be blogging my thoughts about them sporadically throughout the next few months, so be sure to keep checkin’ in on NOL!

Nightcap

- On the inexhaustible desire to keep talking about Marx Jonathan Wolff, Times Literary Supplement

- The promise of polarization Sam Tanenhaus, New Republic

- Anglo-Saxon England was more cosmopolitan than you think Rhiannon Curry, 1843

- DC unfriends Silicon Valley Declan McCullagh, Reason

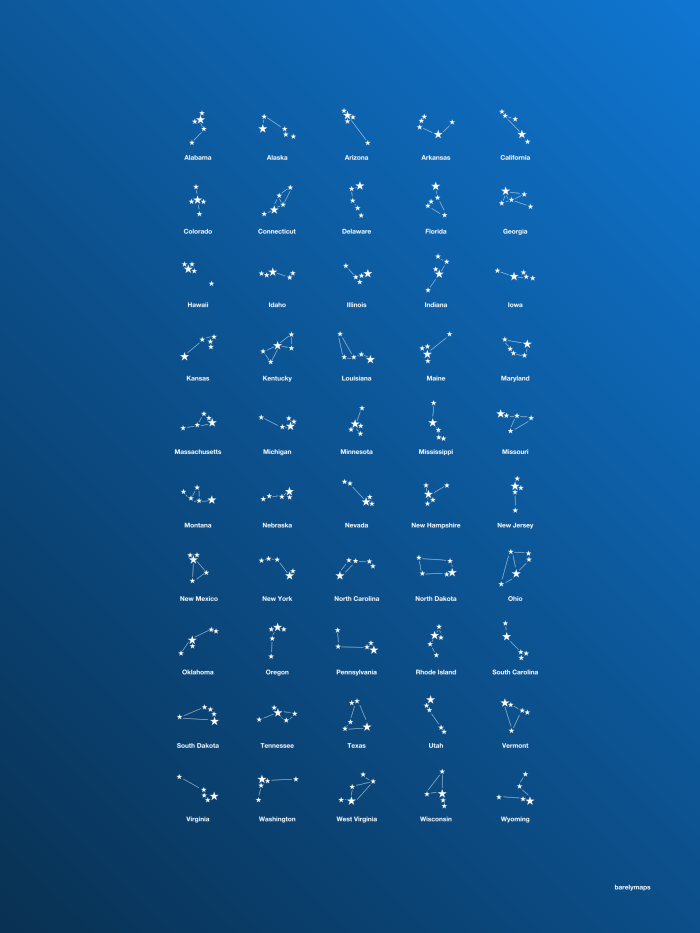

Eye Candy: the five largest cities in each American state, as constellations

Yup, you read that correctly. Behold:

Nightcap

- How did history abdicate its role of inspiring the longer view? Jo Guldi, Aeon

- Third World Burkeans Rod Dreher, American Conservative

- Enemy of The People Pierre Lemieux, EconLog

- Why wasn’t there a Marshall Plan for China? Roderick MacFarquhar, ChinaFile

100 years after World War 1

In the five weeks since the Germans first requested peace negotiations, half a million casualties had been added to the war’s toll. As the delegates talked, Germany continued to collapse from within: inspired by the Russian Revolution, workers and soldiers were forming soviets, or councils. Bavaria proclaimed itself a socialist republic; a soviet took over in Cologne.

And:

But can we really say that the war was won? If ever there was a conflict that both sides lost, this was it. For one thing, it didn’t have to happen. There were rivalries among Europe’s major powers, but in June, 1914, they were getting along amicably. None openly claimed part of another’s territory. Germany was Britain’s largest trading partner. The royal families of Britain, Germany, and Russia were closely related, and King George V and his cousins Kaiser Wilhelm II and Tsar Nicholas II had all recently been together for the wedding of Wilhelm’s daughter in Berlin.

There is more here. Isolationism, or non-interventionism, often sounds good to American libertarians when World War I is brought up and discussed. And who can blame us? I think, though, that non-interventionism is one of the least libertarian positions you could take on matters of foreign policy.

I got an email the other day from an (American) economist who said that he wasn’t an isolationist because he favored free trade and open migration. Instead, he resolutely trotted out the same old dogma that he was a non-interventionist. I’ve got to bury this cognitive failure on the part of American libertarians.

Nightcap

- Mia Love, Trump, and abortion Rachael Larimore, Weekly Standard

- Presidents and the Press — A Brief Modern History Rick Brownell, Medium

- The gatekeeper of Israeli democracy and rule of law Mazal Mualem, Al-Monitor

- Contrarians in public life Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

Afternoon Tea: “‘Chief Princes and Owners of All’: Native American Appeals to the Crown in the Early Modern British Atlantic”

This paper uncovers these indigenous norms by looking at a little-studied legal genre: the appeals made by Native Americans to the British Crown in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. These appeals show that they were aware of (and able to exploit) the complicated politics of the British Atlantic world for their own ends, turning the Crown against the settlers in ways they hoped would preserve their rights, and in the process becoming trans-Atlantic political actors. Focusing on three such appeals – the Narragansetts’ in the mid-seventeenth-century; the Mohegans’ which spanned the first three quarters of the eighteenth; and the Mashpee’s on the eve of the American Revolution – this paper explores the way that these Native peoples in eastern North America were able to resist the depredations of the settlers by appealing to royal authority, in the process articulating a powerful conception of their legal status in a world transformed by the arrival of the English. In doing so, it brings an indigenous voice to the debates about the legalities of empire in the early modern Atlantic world.

This is from Craig Yirush, a historian at UCLA. Here is a link.

Legal Immigration Into the United States (Part 17): Merit-Based Immigration and Other Solutions

The long-established numerical prominence of immigration into the US via family relations makes it difficult to distinguish conceptually between legal immigration responding to matters of the heart and immigration that corresponds to hard economic, and possibly, demographic facts. The one motive has tainted the other and vice-versa. The current public discussions (2016-2018) suggest that many native-born Americans think of immigration as a matter of charity, or of solidarity with the poor of this world, as in the inscription at the foot of the Statue of Liberty: “Give me your tired, your poor, your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,….” Many Americans accordingly perceive as hard-hearted those who wish to limit or reduce immigration. Inevitably, as whenever the subject of hard-heartedness emerges as a topic in politics, a Right/Left divide appears, always to the detriment of the former.

It seems to me that conservatives are not speaking clearly from the side of the divide where they are stuck. They have tacitly agreed to appear as a less generous version of liberals instead of carriers of an altogether different social project. Whatever the case may be, the politically most urgent thing to do from a rational standpoint is to try and divide for good in public opinion, immigration for the heart and immigration for the head, immigration for the sake of generosity and immigration for the benefit of American society. Incidentally, and for the record, here is a digression: I repeat that I believe that American society has a big capacity to admit immigrants under the first guise without endangering itself. That can only happen once the vagueness about controlling our national boundaries has dissipated. Such a strategy requires that the Federal Government have the unambiguous power to select and vet refugees and to pace their admission to the country.

“Merit” Defined

In reaction to the reality and also, of to abuses associated with the current policy, a deliberate, and more realistic doctrine of immigration has emerged on the right of the political spectrum. It asks for admission based on merit, partly in imitation of Australia’s and Canada’s. Canada’s so-called “Express Entry System” is set to admit more than 300,000 immigrants on the basis of formally scored merit in 2118. That’s for a population of only about 37 million. The central idea is to replace the current de facto policy favoring family relations as a ground for admission, resulting in seemingly endless “chain migration,” with something like a point system. The system would attempt scoring an immigrant’s potential usefulness to American society. In its simplest form, it would look something like this: high school graduate, 1 point; able to speak English, 1 point; literate in English, 1 more point; college graduate, 2 points (not cumulative with the single point for being a high school graduate); STEM major, 2 points; certified welder, 2 points; balalaika instructor, 2 points. Rocket scientist with positive record, 5 points. Certified welder, 10 points.

The sum of points would determine the order of admission of candidates to immigration into the US for a set period, preferable a short period because America’s needs may change fast. With the instances I give, this would be a fair but harsh system: Most current immigrants would probably obtain a score near zero, relegating them to eternal wait for admission.

There are two major problems with this kind of policy. First, it would place the Federal Government perilously close to articulating a national industrial policy. Deciding to give several point to software designers and none to those with experience running neighborhood grocery stores, for example, is to make predictions about the American economy of tomorrow. From a conservative standpoint, it’s a slippery slope, from a libertarian standpoint, it’s a free fall. Of course, we know how well national industrial policies work in other countries, France for example. (For 25 years, as a French-speaking professor on the spot, visiting French delegations to my business school would take me aside; they would buy me an expensive lunch and demand that I give away the secret of Silicon Valley. First, create a first rate university, I would answer meanly…)

Second, the conceit that a merit-based system of admission, any merit-based system, is an automatic substitute for the family reunion-dominated current policy is on a loose footing. Suppose, a Chinese woman receives top points in the new system as a world-class nuclear scientist whose poetry was nominated for a Nobel in literature. She walks right to the head of the line, of course. But she is married and she and her husband have three children. Can we really expect her to move to the US and leave her family behind? Do we even want her to, if we expect her to remain? Does anyone? Then, the woman and her husband both turn out to be busy as bees and hard workers, major contributors to the US economy, and to American society in general. (They are both also engaged in lively volunteering.) So, they need help with child care. The husband’s old but still healthy mother is eager and willing to come to live with the couple. She is the best possible baby-sitter for the family. The problem is that the old lady will not leave her even older husband behind. (And, again, would we want her here if she were the kind to leave him?)

Here you go, making ordinary, humane, rational decisions, the merit-based admission of one turns into admission of seven! And, I forgot to tell you: Two of the kids become little hoodlums, as happens in the best families in the second generation. They require multiple interventions from social services. They will both cost society a great deal in the end. In this moderate scenario, the attempt to rationalize immigration into a more selfish policy benefiting Americans has resulted in a (limited) reconstitution of the despised chain immigration, with some of the usual pitfalls.

The arguments can nevertheless be made that in the scenario above, the new merit-based policy has resulted in the admission of upper-middle class individuals rather than in that of the rural, poorly educated immigrants that the old policy tended to select for. This can easily be counted as a benefit but the whole story is probably more complicated. In the exact case described above, the US did replace lower-class individuals with upper-middle class people but also with people possibly of more alien political culture, with consequences for their eventual assimilation. I mean that all Mexicans tend to be experts in Americana and that our political institutions are familiar to them because theirs are copy-cat copies of ours. I surmise further that Mexicans are unlikely from their experience to expect the government to be mostly benevolent. Moreover, it seems to me the children of semi-literate Mexicans whose native language is fairly well related to English and uses the same alphabet, are more likely to master English well than even accomplished Chinese. This is a guess but a well-educated teacher’s guess. (I don’t think this holds true for the grand-children, incidentally.) Of course, if my argument is persuasive, there would be a temptation to down-score candidates just for being Chinese, pretty much the stuff for which Harvard University is on trial as I write (October 2018).

I described elsewhere how the fact of having relatives established in the country facilitates installation and economic integration, even as it may retard assimilation. Note that a point system does not have to forego the advantages associated with family relationships. Such a system can easily accommodate family and other relationships, like this: adult, self-sufficient offspring legally in the US: 3 points; any other relation in the US: 1 point; married to a US resident with a welder certification: 15 points, etc.

[Editor’s note: in case you missed it, here is Part 16]

Nightcap

- The Statue of Liberty is a deeply sinister icon Stephen Bayley, Spectator

- From socialist to left-liberal to neoconservative hawk David Mikics, Literary Review

- Populism in Europe: democracy is to blame, so what is to be done? Philip Manow, Eurozine

- When Medicaid expands, more people vote Margot Sanger-Katz, the Upshot

Legal Immigration Into the United States (Part 16): Toward a One-Party System?

There exists a prospect that continued immigration of the same form as today’s immigration could provide the Democratic Party with an eternal national majority. The US could thus become a de facto one-party state from the simple interplay of demographic forces, including immigration. There are three potential solutions to this problem, the first of which is seldom publicly discussed, for some reason. As the European Union has been showing for thirty years or so, residence in a particular country should not necessarily imply citizenship, the exercise of political rights, in the same country. Ten of thousands of Germans live permanently in France and in Spain. They vote in Germany. (In July 2018, a German woman, thus a citizen of the European Union, who had lived and worked in France for 25 years, and with a French citizen son, was denied French citizenship!) This arrangement, separating residency from citizenship, seems to pose no obvious problem in Europe. (Nikiforov and I discussed this solution in our article in the Independent Review.)

Curiously, in the current narrative, there are no loud GOP voices proposing a compromise with respect to some categories of illegal aliens, I mean, legalization without a path to citizenship. This is puzzling because this is precisely what many illegal aliens says they aspire to. Latin Americans and especially Mexicans frequently say they want to work in the US but would prefer to raise their children back home. (See, for example the good descriptive narrative by Grant Wishard, “A Border Ballad” in the Weekly Standard, 3/9/18.) The simple proposition that easy admission could go with no path to citizenship has the potential to transform immigration to the US, to dry up its illegal branch, and to facilitate border control to a great extent. Yet, there is no apparent attempt to wean immigrants away in this fashion from their Democrat sponsors. The GOP does not seem to have enough initiative to try to reach agreement with immigrant organizations on this basis thus by-passing the Democratic Party. Again, the silence concerning this strategy is puzzling.

In early 2018, President Trump seems to be seeking an answer to the problem of a permanent Democratic takeover by combining the two next solutions. First, would come a reduction in the absolute number allowed to immigrate. Fewer immigrants, fewer Demo voters, obviously. Small government conservatives like me, and rational libertarians also, might simply want to favor reduced immigration as the only sure way to avoid a one-party system even as we believe in the economic and other virtues of immigration.

The second conceptual solution consists in the broad adoption of so-called “merit-based” immigration. There is an unspoken assumption that a merit-based system would produce more middle-class immigrants and, therefore more conservatively oriented immigrants. This assumption is shaky at best. The example of much of the current high-tech Indian immigrants is not encouraging in this respect. More generally, immigrants with college degrees, for example, might turn out more solidly on the left than the current rural, semi-literates from underdeveloped countries who are also avid for upward mobility. The latter also frequently are religious, a condition the Democratic Party is increasingly apt to persecute, at least implicitly. At any rate, reducing the absolute size of immigration carries costs described throughout this essay and merit-based immigration is no panacea, as explained below. I fear that some significant trade-offs between political and other concerns are going to be implemented without real discussion.

[Editor’s note: in case you missed it, here is Part 15]

Nightcap

- Losing the House may actually help Trump more than it hurts him James Rogers, Law & Liberty

- Tyler Cowen on the elections Marginal Revolution

- Clifford Geertz, radical objectivity, and elections Timothy Taylor, Conversable Economist

- Not wearing a poppy Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling