- State anarchy as order (pdf) Hendrick Spruyt, International Organization

- Classical liberalism, world peace, and international order (pdf) Richard Ebeling, IJWP

- Sovereignty in Mesoamerica (pdf) Davenport & Golden, PSP-CM

- The distributive state in the world system (pdf) Jacques Delacroix, SCID

Nightcap

- The colonization cost theory of anarchic emergence (pdf) Vladimir Maltsev, QJAE

- How Africa made the modern world Dele Olojede, Financial Times

- Gorbachev’s Christmas farewell to the Soviet Union Joseph Loconte, National Review

- How I did not celebrate Christmas (in Yugoslavia) Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

Some Monday Links

How Do We Define The Nightmare Before Christmas? (Tor)

How an iconic Canadian rock band lured angry teens to the dark arts of Ayn Rand. (LitHub)

Ill Liberal Arts (The Baffler)

Genghis Khan, Trade Warrior (FED Richmond)

The Misdiagnosis That Continues To Save Lives: Origin Story Of The War On Cancer

In 1969, Colonel Luke Quinn, a U.S. Army Air Force officer in World War II, was diagnosed with inoperable gallbladder cancer. Surprisingly, he was referred to Dr. DeVita, the lymphoma specialist at National Cancer Institute, by the great Harvard pathologist Sidney Farber — famous for developing one of the most successful chemotherapies ever discovered. Nobody imagined back then that Colonel Luke Quinn, a wiry man with grey hair and a fierce frown with his unusual and likely incurable cancer, would significantly impact how we look at cancer as a disease.

Having been coerced to take up the case of Colonel Luke Quinn, despite gallbladder cancers not being his specialty, Dr.DeVita began to take a routine history, much to the annoyance of Luke Quinn who was used to being in command. Though Quinn glared at Dr.DeVita for reinitiating another agonizing round of (im)patient history, he said he had gone to his primary care physician in D.C. when his skin and the whites of his eyes had turned a deep shade of yellow — jaundice. Suspecting obstructive jaundice—a blockage somewhere in the gallbladder, Quinn was referred to Claude Welch, a famous abdominal surgeon at Mass general who had treated Pope John Paull II when he was shot in 1981. Instead of gallstones, the renowned surgeon found a tangled mass of tissue squeezing Quinn’s gallbladder—gallbladder cancer was pretty much a death sentence. On the pathologist’s confirmation, Quinn, being declared inoperable, was sent to Dr.DeVita at NCI as he wanted to be treated near his home.

Dr.DeVita, however, noticed something quite odd when he felt Quinn’s armpits during a routine examination. Quinn’s axillary lymph nodes—the cluster of glands working as a sentinel for what’s going on in the body—under his arms were enlarged and rubbery. These glands tend to become tender when the body has an infection and hard if it has solid tumors—like gallbladder cancer; they become rubbery if there is lymphoma. Being a lymphoma specialist, the startled Dr. DeVita questioned the possibility of a misdiagnosis—what if Quinn had lymphoma, not a solid tumor wrapping around his gallbladder leading to jaundice?

On being asked for his biopsy slides to be reevaluated, the always-in-command Colonel Luke Quinn angrily handed them over to the pathologist at NCI and sat impatiently in the waiting room. Costan Berard, the pathologist reviewing Quinn’s biopsy slides, detected an artifact in the image that had made it difficult to differentiate one kind of cancer cell from the other. Gallbladder cancers are elliptical, whereas Lymphoma cells are round. The roundish lymphoma cells can look like the elliptical gallbladder cancer cells when squeezed during the biopsy. This unusual finding by Berard explained why Quinn’s lymph nodes were not hard but rubbery. The new biopsy showed without a doubt that Quinn had non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma —the clumsy non-name we still go by to classify all lymphomas that are not Hodgkin’s disease.

The NCI was working on C-MOPP, a new cocktail of drugs to treat non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma that had shown a two-year remission in forty percent of aggressive versions of this disease. The always-in-command WW II veteran had somehow landed in the right place by accident! It was a long three months for the nurses though, as they hated him for leaning on the call button all-day, for complaining bitterly about the food, for chastising anyone who forgot to address him, Colonel Quinn, and for never thanking anyone. But incredibly, he was discharged without any sign of his tumor; he had gone from certain death to a fighting chance.

The fierce and unpleasant Colonel Quinn is crucial because his initial misdiagnosis unknowingly spurred the creation of a close network of influential people during his remarkable escape from certain death. He could do this because he was a friend and employee of the socialite and philanthropist Mary Lasker—the most consequential person in the politics of medical research. Read my earlier piece on her.

Mary Lasker, the timid, beehived socialite circumvented all conventions of medical research management and got the U.S. Congress to do things her way. Mary’s mantra was: Congress never funds a concept like “cancer research,” but propose funding an institute named after a feared disease, and Congress leaps on it. Her incessant lobbying with the backing of her husband, Albert Lasker and her confidante, Florence Mahoney, wife of the publisher of The Miami News, helped create the National Cancer Institute, the National Heart Institute, the National Eye Institute, the National Institute of Mental Health, the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, the National Institute of Arthritis and Metabolic Diseases, the National Institute of Aging, and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Though Mary Lasker knew the value of independent investigators pursuing their unique research interests, she supported projects only when a clinical goal was perceptible, like curing tuberculosis. In 1946, Mary, having noticed microbiologist Selman Waksman’s work on streptomycin—a new class of antibiotics effective against microbes resistant to penicillin—persuaded him and Merck pharmaceutical company to test the new drug against TB. By 1952 Mary’s instinct had won over Waksman’s initial skepticism as the widespread use of streptomycin halved the mortality from TB! Mary Lasker’s catalytic influence on basic research leading to a Nobel Prize-winning discovery is a case in point.

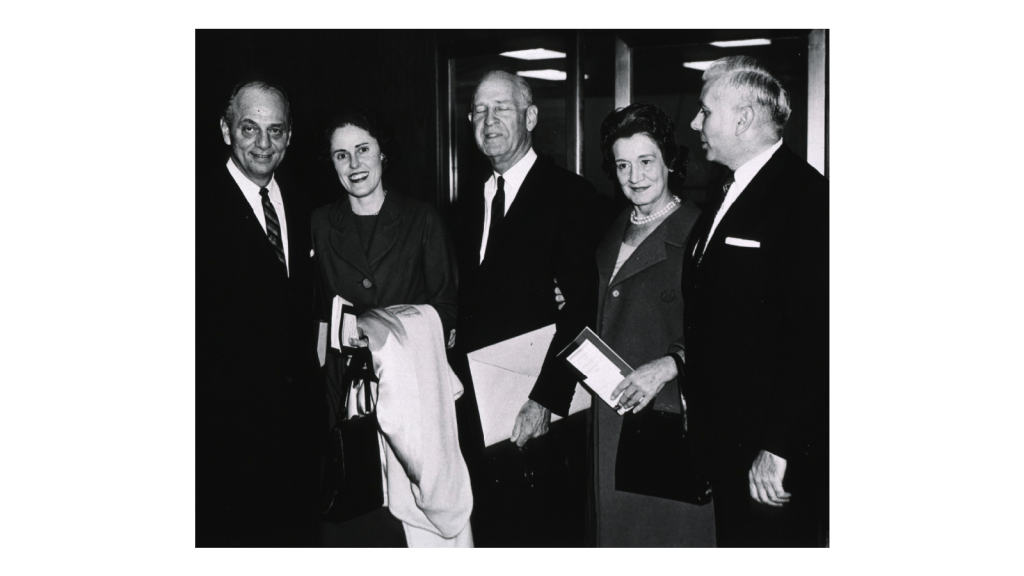

Her clout over Congress was in its prime through the 1950s and 60s when the National Cancer Institute (NCI) was developing the first cancer cures. It was also the period when Colonel Luke Quinn became her influential lieutenant. The Congress believed Luke Quinn represented the American Cancer Society, but he was Mary’s lobbyist in reality. When Quinn got sick, Mary used her contacts to get Welch and Sidney Farber, but it got her special attention when Quinn’s incurable torment was overcome. The ongoing public concern for cancer and Albert Lasker’s death due to pancreatic cancer made it an ideal disease for Mary to draw the battle lines. Quinn’s recovery convinced her that the necessary advance in basic research had occurred to justify taking the disease head-on. In April 1970, she began building bipartisan support by having the Senate create the National Panel of Consultants on the Conquest of Cancer. She prevailed over the Texas Democrat senator Ralph Yarborough to appoint her friend, a wealthy Republican businessman Benno C. Schmidt —the chairman of Memorial Sloan Kettering board of managers—to be the chairman on the conquest of cancer panel. She backed him up by arranging Sidney Farber as the co-chairman. The panel also included Colonel Luke Quinn and Mary herself.

In just six months, the panel issued “The Yarborough Report.” The report, mainly written by Colonel Luke Quinn and Mary Lasker, made far-reaching recommendations, including an independent national cancer authority. It recommended a substantial increase in funding for cancer research from $180 million in 1971 to $400 million in 1972 and reaching $1 billion by 1976. Finally, it recommended that the approval of anticancer drugs be moved from the FDA to the new cancer authority. Senator Edward Kennedy presented the recommendations as new legislation for the Ninety-Second Congress. Though not a Senate staff member, Colonel Quinn, trained by Mary in the art of testifying before the Congress, orchestrated the hearings, set the agenda, and selected the people who would testify.

The Nixon administration did not immediately embrace the bill as he wasn’t thrilled by Edward Kennedy’s involvement. Being Ted Kennedy’s close friend, Mary asked him to withdraw as a sponsor. Under Senator Pete Domenici, the bill renamed the National Cancer Act had to pass in the House. Paul Rogers, who headed the House Health subcommittee—Colonel Quinn and Mary Lasker had no influence over him—objected to removing the NCI from the NIH umbrella. He cautioned the NIH would face similar threats of separation in other disease areas. A revised bill agreed to this demand and kept the NCI under the NIH but gave it a separate budget and a director appointed by the President.

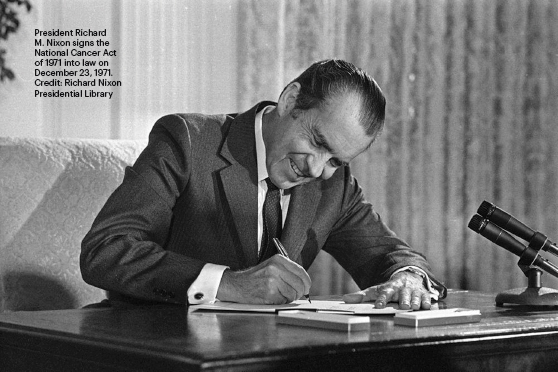

On December 23, 1971— fifty years to this day—the National Cancer Act was signed as a Christmas gift to the nation by President Richard Nixon, two years after Colonel Luke Quinn walked into the NCI with a wrong diagnosis. Though Quinn ultimately died of his relapsed cancer, a few months after the signing of the Cancer Act, the war on cancer had commenced with cancer research on the fast track. It was a victory for Mary Lasker, perhaps the most effective advocate for biomedical research that Washington had ever seen.

In hindsight, Mary Lasker’s triumph came with two significant disappointments. First, her crusade had failed in transferring the authority for approval of anticancer drugs from the FDA to the NCI—a failure that would plague the National Cancer Program well into the future. Second, the premise of the National Cancer Act that the “basic science was already there” and a quantitative boost in resources was all that was needed to bring victory was flawed. In combination, the two disappointments—the subjects of a future blog post—have spotlighted a perceived progress gap in cancer research by the tax-paying general public rather than underlining the tremendous conceptual progress made due to the War on Cancer.

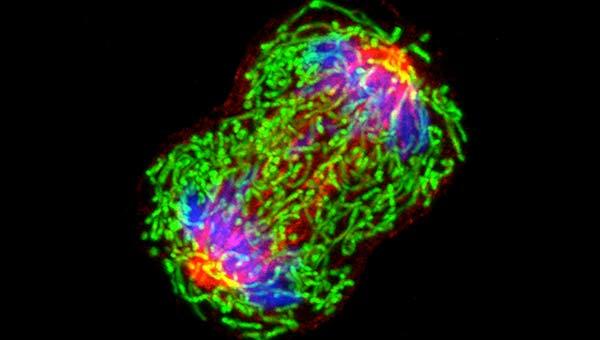

Credit: National Cancer Institute / Univ. of Pittsburgh Cancer Institute

Ultimately, this blog is for you to appreciate the 50th anniversary of the lucky accidents and the incredible effort in creating the National Cancer Act. At the same time, personally, cancer researchers—the boots on the ground—like me who experience the non-triviality of progress in cancer will dwell on the insistence of simplistic linear views of progress in cancer research for public consumption.

Book list triple threat

Neither new books, nor in any particular order. Hell, did not even read them all in 2021.

Fiction

- Mistborn trilogy – Gripping enough, long slog, well-thought magic system. (Brandon Sanderson)

- The Alloy of Law, a sequel that became the 1st part of another Mistborn trilogy. Gritty steampunk setting, the mix & match of magic powers didn’t do it for me. Meh. (Brandon Sanderson)

- Reckoners trilogy – Almost fine for YA. Forgettable. (Brandon Sanderson)

- Earthsea Quartet – Rich and beautiful, seems a bit dated or familiar, since it set standards encountered in later works in the genre. (Ursula Le Guin)

- Farseer trilogy – Intricate world building, the 1st person POV suits. Curiously, the 2nd book is the best of the series. (Robin Hobb)

Prose-wise, Le Guin and Hobb lead by a wide margin vs Sanderson. The two also go beyond the usual hack-n-slash and shed light to the more mundane labors of daily life in a largely medieval world. A documentary on castles/ forests/ ports could certainly use a few of Hobb’s descriptions and terms.

- The Lacquer Screen – A detective novel set in Imperial China, of a particular subgenre called gong’an. I enjoyed the ambience of Tang period, while the whole read is quite old-fashioned. (Robert van Gulik)

Comic Books

- Watchmen – Superb. (Moore/ Gibbons)

- Batman: The Dark Knight Returns – I expected to like it more, I think. (Miller)

- Blacksad (#1-5, integrated version) – Sublime artwork, storylines good but uneven. I had already read #1-3 some 15 years ago. (Canales/ Guarnido)

On the pile

- The dispossessed (Ursula Le Guin)

- Watership Down (Richard Adams)

- Ship of Magic (Robin Hobb)

- Superman: Red Son (Millar/ Johnson/ Robinson/ Wong/ Plunkett)

- Batman: White Knight (Murphy)

And a sole non-fiction entrant to the pile:

- The Body: A Guide for Occupants (Bill Bryson)

The Aussie-UK Free Trade Agreement

Introduction

Australia and the UK signed a Free Trade Agreement (FTA) on December 17, 2021 (an in principle agreement had been announced in June 2021). This FTA will drastically reduce tariffs on a number of Australian exports to the UK and reduce duties on a number of British commodities to Australia. Significantly, it will also make it easier for both Australian and British workers to work in each other’s countries under the working holiday scheme (WHS).

According to estimates of the British government, the FTA could increase trade between the United Kingdom and Australia by approximately $19 billion “in the long run” while the UK’s GDP may increase by about $4.2 billion by 2035.

There are some important provisions which could benefit workers from both countries. Firstly, in an important step, both countries have increased the working holiday visa’s eligible age to 35. What is especially significant is that there is no pre-requisite for applicants under this category to be employed in any “specific work.” Second, Australia will permit up to 1,000 workers to come from the UK in the first year of a new “skills exchange” trial.

Symbolic importance of the FTA

In a post-pandemic world, society is becoming even more insular and borders are becoming more stringent, so encouraging professionals and workers is important. In June 2021, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson had said:

We’re opening up to each other and this is the prelude to a general campaign of opening up around the world.

The UK’s Secretary of State for International Trade, Anne Marie Trevelyan, described the deal as “a landmark moment in the historic and vital relationship between our two Commonwealth nations.”

The geopolitical significance of the FTA

From the UK’s point of view the FTA is important because the UK has been seeking to become more pro-active in the Indo-Pacific. Australia has been one of the most vocal proponents of the Free and Open Indo Pacific, and is also one of the members of the Quad (the other three members are the US, Japan, and India). From an economic standpoint the FTA is agreeable because the UK is seeking to get on board the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) (members of this group have a combined GDP of $13.5 trillion), and this deal will only bolster its chances. The UK has already signed trade agreements with two members of the CPTPP — Japan and Vietnam – in 2020. Interestingly the TPP (Trans Pacific Partnership), the precursor to the CPTPP, was conceived by former US President Barack Obama, but the US withdrew from the agreement during the Trump Administration (pulling the US out of the TPP was one of the first decisions taken by Donald Trump after he took over as President). The trade agreement had also been opposed by a number of Democrat leaders including Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders.

For Australia, this agreement is especially significant because ever since the souring of relations with China, the bilateral economic relationship has been adversely impacted. China has imposed tariffs on a number of commodities, such as wine and barley, and also restricted imports of Australian beef, coal, and grapes. Under the Australia-UK FTA, tariffs on Australian wines will be terminated immediately, and the FTA will give a boost to the sales of not just wine but a number of other commodities boycotted by China. The FTA with the UK may not be able to compensate for the economic ramifications of strained ties with China, but it could pave the way for Australia exploring similar arrangements with a number of other countries.

In conclusion, the agreement between Australia and the UK is an important development and a clear reiteration of the point that the UK has an important role to play as a stakeholder in the vision of the “Free and Open Indo Pacific.” Second, the Indo Pacific needs to have a strong economic component and FTAs between countries are important in this context. Third, countries like Australia willing to bear the economic ramifications of a deterioration in ties with China need to look at alternative markets for their commodities. Finally, while there are certain areas where only the US can provide global leadership, US allies need to chart their own course, as is evident not only from FTAs signed between many of them, but also by the success of the CPTPP without the US being on board.

Some Monday Links

The First World War battle that actually went to plan (Prospect)

The Eyes Have It (Quillette)

Kinship Is a Verb (Orion)

Vishnu used a similar play of words here.

How the University of Austin Can Change the History Profession (Law & Liberty)

New York, plus ça change: Chinatown under threat (Crimereads)

The Quad of West Asia: New Developments, Old Problems

Introduction

The signing of the Abraham Accords in September 2020, through which Bahrain and the UAE normalised ties with Israel, was a significant development which analysts believed had the potential of altering the geopolitical dynamics of the Middle East. In December 2020, Morocco also signed an agreement for normalising relations with Israel, while in January 2021, Sudan followed suit. The 2020 accords, which many believed was more about symbolism than substance, drew criticism for ignoring the Israeli-Palestinian conflict (the events of May 2021 clearly reiterate this point) and overlooking other complexities of the region.

Hailed by the Biden Administration

The Abraham accords, which have been dubbed as one of the significant achievements of the erstwhile Trump Administration, were welcomed by Biden (who was then not President) and have been hailed by him and by senior officials within his administration repeatedly. Commenting on the Abraham Accords at the one-year anniversary, US Secretary of State Anthony Blinken said: “Today, a year after the Accords and normalization agreements were signed, the benefits continue to grow.”

Israel opened a consulate in the UAE in June 2021, while the UAE opened a consulate in Tel Aviv in July 2021.

Abraham accords and UAE-Israel ties

The accords have also given a boost to economic ties between both the Emirates and Israel (Israeli Foreign Minister Yair Lapid said that bilateral trade between both countries had surpassed $600 million in June 2021, less than a year after signing of the Abraham Accords). In the past year alone there has been a significant jump in Israeli tourists visiting the UAE (Israel, on its part, is also trying to woo tourists from the UAE). In October 2021, the Foreign Ministers of the US, the UAE, Israel, and India met and discussed potential areas of cooperation – specifically trade, infrastructure, technology, and maritime cooperation. This grouping has even been dubbed as a new ‘Quad’ in West Asia. US State Department spokesperson Ned Price, while commenting on the thrust of the meeting, said that the four countries:

discussed expanding economic and political cooperation in the Middle East and Asia, including through trade, combating climate change, energy cooperation, and increasing maritime security.

UAE’s outreach to Iran and its impact on UAE-Israel ties

While improving ties with Israel, the UAE has also been reaching out to Iran (economic ties between both countries remained robust even in the midst of tensions). Iranian Foreign Minister Hossein Amir-Abdollahian said, in a telephonic conversation last month with UAE Foreign Minister Sheikh Abdullah bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan, that Tehran attached great importance to its ties with the UAE and that it was important to give a boost to bilateral economic linkages.

National Security Advisor of the UAE, Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan, led a high profile Emirati delegation to Iran on December 6, 2021 and met with his counterpart, Admiral Ali Shamkhan (the Iranian National Security Adviser), as well as Iranian president Ebrahim Raisi, and discussed bilateral and regional issues. This visit came days after the Vienna talks pertaining to the revival of the JCPOA (Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action)/Iran nuclear deal had broken down on December 3, 2021 (both the US and several EU countries had blamed Iran for its rigid approach). Dr Anwar Mohammed Gargash, diplomatic adviser to the UAE’s president, said that Sheikh Tahnoon bin Zayed Al Nahyan’s visit to Iran:

comes as a continuation of the UAE’s efforts to strengthen bridges of communication and cooperation in the region which would serve the national interest.

While the UAE is a key player in the Middle East and could play an important role in talks pertaining to the Iran Nuclear deal, both Israel and the US would be watching the attempts by the UAE to reach out to Iran. Many analysts argue that the Emirates could show lesser interest in getting other Gulf countries to normalize relations with Israel (Saudi Arabia, arguably the most influential country in the Arab Gulf, has also stated that it could not normalize ties with Israel without a sustainable resolution to the Palestinian-Israeli conflict).

UAE-China-US trilateral

Another important point to bear in mind is that there have been differences between the US and the UAE after the former alleged that China was building a military installation inside the Khalifa port, not far from the capital city of the Emirates, Abu Dhabi (this construction was halted after discussions between senior US officials and their UAE counterparts).

The UAE shares close strategic ties with the US (the latter has 3,500 of its troops based at Al Dhafra air base, which is 30 kilometres from Abu Dhabi), but the sale of fifty F35 stealth fighter planes (worth $23 billion) has been delayed for a number of reasons: Abu Dhabi’s use of Huawei 5 technology, the presence of China at strategically important points, and the offer of military technology by Beijing to the UAE. The agreement for the sale of F35s to the UAE had been signed during the Trump Administration.

The UAE has the ability to reinvent itself and this has stood it in good stead in the economic sphere; it will now need to recalibrate its foreign policy and keep it in sync with the geopolitical developments in the Middle East (the geopolitical landscape of the region has changed significantly ever since the signing of the Abraham accords). Its biggest regional challenge will be to maintain cordial ties with Israel and Iran, and at a global level ensuring that its strategic ties with the US do not get impacted by its cordial ties with China. In the midst of all the challenges and complexities, the UAE could leverage its ties with Iran to reduce tensions between the West and Tehran.

From the comments: Kinship networks and U.S. politicians

So kinship necessarily expands the utility and probability of shared interests measurably, a path of study likely threatening to politicians … It might be fun to see a kinship matrix for current U.S. politicians ..?

“Blood is Thicker Than Water: Elite Kinship Networks and State Building in Imperial China”

A long tradition in social sciences scholarship has established that kinship-based institutions undermine state building. I argue that kinship networks, when geographically dispersed, cross-cut local cleavages and align the incentives of self-interested elites in favor of building a strong state, which generates scale economies in providing protection and justice throughout a large territory. I evaluate this argument by examining elite preferences related to a state-building reform in 11th century China. I map politicians’ kinship networks using their tomb epitaphs and collect data on their political allegiances from archival materials. Statistical analysis demonstrates that a politician’s support for state building increases with the geographic size of his kinship network, controlling for a number of individual, family, and regional characteristics. My findings highlight the importance of elite social structure in facilitating state development and help understand state building in China – a useful, yet understudied, counterpoint to the Euro-centric literature.

Some Monday Links (extend, not pretend version)

The Strange Career of Paul Krugman (Tablet)

If anything, it warrants at least some praise for finally giving a date to an oft-cited, curiously undated essay by Krugman, Ricardo’s difficult idea.

Learning Sixteenth-Century Business Jargon (Lapham’s Quarterly)

Brainwashing has a grim history that we shouldn’t dismiss (Psyche)

Another Case Against Science’s Objectivity Myth: Nepotism in Publishing (The Wire Science)

Who Controls the Narrative?: On David M. Higgins’s “Reverse Colonization: Science Fiction, Imperial Fantasy, and Alt-Victimhood” (LA Review of Books)

Hasui Kawase’s Beautiful Prints of Japanese Landscapes (Flashbak)

“Federations, coalitions, and risk diversification”

[…] while we recognize that issues of participation in a coalition involve complex factors, there has been little discussion in the literature from a risk-sharing perspective. It is well-known in financial economics that the pooling of resources and the spreading of risk allows investors to realize a rate of return that approaches the expected rate. We take this to be a natural motive for federation formation among a group of regions. Indeed, the existence of an ancient state in China (the example given in the next section) supports our intuition. It appears that floods, droughts and the ability of a centralized authority to diversify risk paved the way for the unification of China as early as 2000 years ago. Thus, our approach is not empirically irrelevant.

Click the “pdf” tab on the right-hand side, not the “buy PDF” tab.

Some Monday Links: The food issue

Communism Destroyed Russian Cooking (Reason)

How did pizza first appear in the Soviet Union? (Russia Beyond)

How Not To Feed the Hungry: A Symposium (Law & Liberty)

Vintage Thanksgiving Postcards Are Bizarre (Hypperallergic)

HIGH DEMAND FOR HIGH CHEEKBONES

New York Post reports that another prominent “Pocahontas” has been exposed as a fraud. The most recent one was American “Cherokee” Senator Elizabeth Warren who had masqueraded as a woman of “color” to have a good boost in her early career of a lawyer and academic; later, when exposed, she became a butt of jokes for drawing attention to her “indigenous” high cheekbones. Now it is “Canadian Metis” Carrie Bourassa, scientific director of the Canadian Institutes of Health Research’s Institute of Indigenous Peoples’ Health. I wonder why they so eagerly seek to pass for Indians and join the “oppressed.” I suspect that the moral, political, and financial pie that society of “systemic racism” offers to real, partial, and aspiring Indians is so rich and tasty that it is unbearably hard to resist a temptation not to have a bite of it. Incidentally, her detractors, who became suspicious that she was not a true Indian “Aryan,” do not even catch the irony of the whole situation: Bourassa claimed the Metis lineage; the Metis is a group that had in fact originated as the offspring of Native Americans (or First Nations, according the Canadian political jargon) and early Europeans; therefore, by default they are already not true “Aryans.” Yet, along with the “First Nations,” the Metis have been recognized by the Canadian government as a historically oppressed group that has been singled out for a special political, social, and financial treatment as a protected community. When a government creates moral and financial incentives to be indigenous, it unavoidably has to deal with the host of emerging “tribes,” “first nations,” and “high cheekbone” individuals on both sides of the US-Canadian border. In the meantime, let’s wait for a next episode of that exciting post-Modern politico-economic western that has been on for the past fifty years.