In 1945, Friedrich A. Hayek published under the title “The Use of Knowledge in Society,” in The American Economic Review, one of his most celebrated essays -both at the time of its appearance and today- and probably, together with other studies also later compiled in the volume Individualism and Economic Order (1948), one of those that have earned him the award of the Nobel Prize in Economics, in 1974.

His interpretation generates certain perplexities about the meaning of the term “knowledge”, which the author himself would clear up years later, in the prologue to the third volume of Law, Legislation and Liberty (1979). Being his native language German, Hayek explains there that it would have been more appropriate to have used the term “information”, since such was the prevailing meaning of “knowledge” in the years in which such essays had been written. Incidentally, a similar clarification is also made regarding the confusions raised around the “spontaneous order” turn, which he later replaced by that of “abstract order”, with further subsequent replacements:

“Though I still like and occasionally use the term ‘spontaneous order’, I agree that ‘self-generating order’ or ‘self-organizing structures’ are sometimes more precise and unambiguous and therefore frequently use them instead of the former term. Similarly, instead of ‘order’, in conformity with today’s predominant usage, I occasionally now use ‘system’. Also ‘information’ is clearly often preferable to where I usually spoke of ‘knowledge’, since the former clearly refers to the knowledge of particular facts rather than theoretical knowledge to which plain ‘knowledge’ might be thought to prefer” . (Hayek, F.A., “Law, Legislation and Liberty”, Volume 3, Preface to “The Political Order of a Free People”.)

Although it is already impossible to substitute in current use the term “knowledge” for “information” and “spontaneous” for “abstract”; it is worth always keeping in mind what ultimate meaning should be given to such concepts, at least in order to respect the original intention of the author and perform a consistent interpretation of his texts.

By “the use of knowledge in society”, we will have to refer, then, to the result of the use of information available to each individual who is inserted in a particular situation of time and place and who interacts directly or indirectly with countless of other individuals, whose special circumstances of time and place differ from each other and, therefore, also have fragments of information that are in some respects compatible and in others divergent.

In the economic field, this is manifested by the variations in the relative scarcity of the different goods that are exchanged in the market, expressed in the variations of their relative prices. An increase in the market price of a good expresses an increase in its relative scarcity, although we do not know if this is due to a drop in supply, an increase in demand, or a combined effect of both phenomena, which vary joint or disparate. The same is true of a fall in the price of a given good. In turn, such variations in relative prices lead to a change in individual expectations and plans, since this may mean a change in the relationship between the prices of substitute or complementary goods, inputs or final products, factors of production, etc. In a feedback process, such changes in plans will in turn generate new variations in relative prices. Such bits of information available to each individual can be synthesized by the price system, which generates incentives at the individual level, but could never be concentrated by a central committee of planners. In the same essay, Hayek emphasizes that such a process of spontaneous coordination is also manifested in other aspects of social interactions, in addition to the exchange of economic goods. They are the spontaneous –or abstract- phenomena, such as language or behavioral norms, which structure the coordination of human interaction without the need for a central direction.

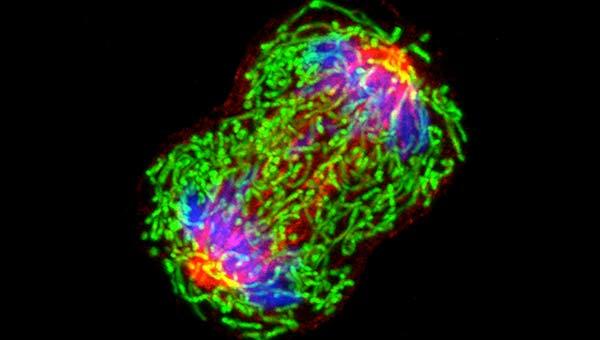

“The Use of Knowledge in Society” appears halfway through the life of Friedrich Hayek and in the middle of the dispute over economic calculation in socialism. His implicit assumptions will be revealed later in his book The Sensory Order (1952) and in the already mentioned Law, Legislation and Liberty (1973, 1976 and 1979). In the first of them, we can find the distinction between relative limits and absolute limits of information / knowledge. The relative ones are those concerning the instruments of measurement and exploration: better microscopes, better techniques or better statistics push forward the frontiers of knowledge, making it more specific. However, if we go up in classification levels, among which are the coordination phenomena between various individual plans, which are explained by increasingly abstract behavior patterns, we will have to find an insurmountable barrier when configuring a coherent and totalizer of the social order resulting from these interactions. This is what Hayek will later call the theory of complex phenomena.

The latter was collected in Law, Legislation and Liberty, in which he will have to apply the same principles enunciated incipiently in “The Use of Knowledge in Society” regarding the phenomena of spontaneous coordination of individual life plans in the plane of the norms of conduct and of the political organization. Whether in the economic, legal and political spheres, the issue of the impossibility of centralized planning and the need to trust the results of free interaction between individuals is found again.

In this regard, the Marxist philosopher and economist Adolph Löwe argued that Hayek, John Maynard Keynes, and himself, considered that such interaction between individuals generated a feedback process by itself: the data obtained from the environment by the agents generated a readjustment of individual plans, which in turn meant new data that would readjust those plans again. Löwe stressed that both he and Keynes understood that they were facing a positive feedback phenomenon (one deviation led to another amplified deviation, which required state intervention), while Hayek argued that the dynamics of society, structured around values such like respect for property rights, it involved a negative feedback process, in which continuous endogenous readjustments maintained a stable order of events. Hayek’s own express references to such negative feedback processes and to the value of cybernetics confirm Lowe’s assessment.

Today, the dispute over the possibility or impossibility of centralized planning returns to the public debate with the recent developments in the field of Artificial Intelligence, Internet of Things and genetic engineering, in which the previous committee of experts would be replaced by programmers, biologists and other scientists. Surely the notions of spontaneous coordination, abstract orders, complex phenomena and relative and absolute limits for information / knowledge will allow fruitful contributions to be made in such aspects.

It is appropriate to ask then how Hayek would have considered the phenomenon of Artificial Intelligence (A.I.), or rather: how he would have valued the estimates that we make today about its possible consequences. But to adequately answer such a question, we must not only agree on what we understand by Artificial Intelligence, but it is also interesting and essential to discuss, prior to that, how Hayek conceptualized the faculty of understanding.

Friedrich Hayek had been strongly influenced in his youth by the Empirical Criticism of his teacher Ernst Mach. Although in The Sensory Order he considers that his own philosophical version called “pure empiricism” overcomes the difficulties of the former as well as David Hume’s empiricism, it must be recognized that the critique of Cartesian Dualism inherited from his former teacher was maintained by Hayek -even in his older works- in a central role. Hayek characterizes Cartesian Dualism as the radical separation between the subject of knowledge and the object of knowledge, in such a way that the former has the full capabilities to formulate a total and coherent representation of reality external to said subject, but at the same time consists of the whole world. This is because the representational synthesis carried out by the subject acts as a kind of mirror of reality: the res intensa expresses the content of the res extensa, in a kind of transcendent duplication, in parallel.

On the contrary, Hayek considers that the subject is an inseparable part of the experience. The subject of knowledge is also experience, integrating what is given. Hayek, thus, also relates his conception of the impossibility for a given mind to account for the totality of experience, since it itself integrates it, with Gödel’s Theorem, which concludes that it is impossible for a system of knowledge to be complete and consistent in terms of its representation of reality, thus demolishing the Leibznian project of the mechanization of thought.

It is in the essays “Degrees of Explanation” and “The Theory of Complex Phenomena” –later collected in the volume of Studies in Philosophy, Politics, and Economics, 1967- in which Hayek expressly recognizes in that Gödel’s Theorem and also in Ludwig Wittgenstein’s paradoxes about the impossibility of forming a “set of all sets” his foundation about the impossibility for a human mind to know and control the totality of human events at the social, political and legal levels.

In short, what Hayek was doing with this was to re-edit the arguments of his past debate on the impossibility of socialism in order to apply them, in a more sophisticated and refined way, to the problem of the deliberate construction and direction of a social order by part of a political body devoid of rules and endowed with a pure political will.

However, such impossibility of mechanization of thought does not in itself imply chaos, but on the contrary the Kosmos. Hayek rescues the old Greek notion of an uncreated and stable order, which relentlessly punishes the hybris of those who seek to emulate and replace the cosmic order, such as the myth of Oedipus the King, who killed his father and married his mother, as a way of creating himself likewise and whose arrogance caused the plague in Thebes. Like every negative feedback system, the old Greek Kosmos was an order which restored its lost inner equilibrium by itself, whose complexities humiliated human reason and urged to replace calculus with virtue. Nevertheless, what we should understand for that “virtue” would be a subject to be discussed many centuries later from the old Greeks and Romans, in the Northern Italy of the Renaissance.