I’ve discovered and admired a wide variety of original thinkers during my eleven-year stay in the United States, from philosopher Eric Hoffer to economist and social theorist Thomas Sowell. From American history professor Barbara J. Fields to American political philosopher Harvey Mansfield. From Tyler Cowen, an American economist, and David Boaz, a libertarian thinker, to Paul Graham, an English-born American venture capitalist and essayist. One among them is Natasha Trethewey, a two-time US Poet Laureate.

My favorite contemporary American poet, Natasha Trethewey’s poems have an Ekphrastic quality because she graphically and implicitly explores her individuality and deprivations of liberty through deeply evocative accounts of her past and personal photographs rooted in her experience of race and culture.

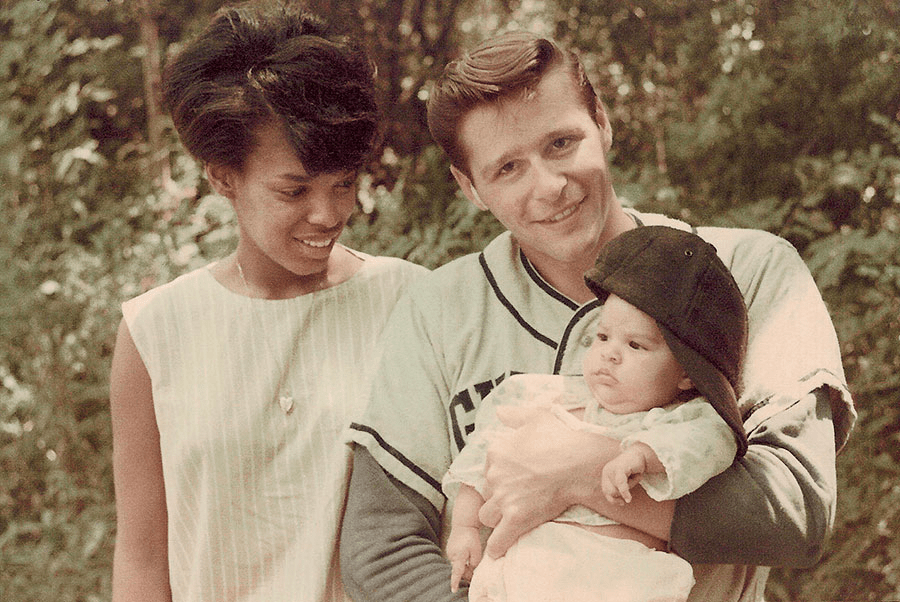

As it is World Poetry Day, I thought I’d share three of her poems that appeal to me. But first, a little background on her: She was born on the centennial of Confederate Memorial Day in the Deep South to an African American mother and a white father when interracial marriage was still illegal in Mississippi. Though her father, poet Eric Trethewey, had an early impact on her, her mother, Gwendolyn Ann Turnbough’s tragic death, according to Trethewey, prompted her first attempt at writing poetry.

I hope you enjoy these poems and explore more of her work.

History Lesson

I am four in this photograph, standing

on a wide strip of Mississippi beach,

my hands on the flowered hips

of a bright bikini. My toes dig in,

curl around wet sand. The sun cuts

the rippling Gulf in flashes with each

tidal rush. Minnows dart at my feet

glinting like switchblades. I am alone

except for my grandmother, other side

of the camera, telling me how to pose.

It is 1970, two years after they opened

the rest of this beach to us,

forty years since the photograph

where she stood on a narrow plot

of sand marked colored, smiling,

her hands on the flowered hips

of a cotton meal-sack dress.

[Natasha Trethewey, “History Lesson” from Domestic Work.]

Southern History

Before the war, they were happy, he said.

quoting our textbook. (This was senior-year

history class.) The slaves were clothed, fed,

and better off under a master’s care.

I watched the words blur on the page. No one

raised a hand, disagreed. Not even me.

It was late; we still had Reconstruction

to cover before the test, and — luckily —

three hours of watching Gone with the Wind.

History, the teacher said, of the old South —

a true account of how things were back then.

On screen a slave stood big as life: big mouth,

bucked eyes, our textbook’s grinning proof — a lie

my teacher guarded. Silent, so did I.

[Natasha Trethewey, “Southern History” from Native Guard.]

Flounder

Here, she said, put this on your head.

She handed me a hat.

You ’bout as white as your dad,

and you gone stay like that.

Aunt Sugar rolled her nylons down

around each bony ankle,

and I rolled down my white knee socks

letting my thin legs dangle,

circling them just above water

and silver backs of minnows

flitting here then there between

the sun spots and the shadows.

This is how you hold the pole

to cast the line out straight.

Now put that worm on your hook,

throw it out and wait.

She sat spitting tobacco juice

into a coffee cup.

Hunkered down when she felt the bite,

jerked the pole straight up

reeling and tugging hard at the fish

that wriggled and tried to fight back.

A flounder, she said, and you can tell

’cause one of its sides is black.

The other side is white, she said.

It landed with a thump.

I stood there watching that fish flip-flop,

switch sides with every jump.

[Natasha Trethewey, “Flounder” from Domestic Work.]

Talking about Trethewey’s poetry, Jericho Brown, a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, says, “Her contribution is that of someone who sees us in individual and human ways and not only representations of resistance. Her black Union soldiers fall in love, her overworked grandmother plays a mischievous trick on a foreman, her black stepfather is a murderer, and her white father, who loves her, can’t resist microaggressions against her. I mean she allows her characters — her own history — to be as complex as history really is. This makes space for readers like me who are interested in life and not a caricature of life, readers who understand that poems must face us to our good and our evil and our personhood no matter what color we are.” Apart from Brown’s insight into Trethewey’s poetry invoking a strand of individuality that goes beyond trying to paint groups of people as symbols of resistance, I have often wondered what it is about her poems that appeal to me. Though I have no firsthand experience of what a troubled relationship with racial identity feels like, I suppose it may have something to do with my uneasy alliance with the English language itself—the medium of Trethewey’s craft. English is both the language of enslavement and revolt in a multilingual India. Though a colonial language, India has adopted English as its father tongue, yet we don’t fall under the Anglosphere-type of society. For most Indians, including me, English is characterized by ambiguity and conflict with our mother tongues, often mirroring a flounder-like situation—flip-flopping, switching sides with every jump, privileging one or the other, yet interpreting each other in the search for liberty.

Here’s some more from Natasha Trethewey