- Between populism and internationalism: conservative foreign policy after Trump Colin Dueck, War on the Rocks

- Recovering the profound divisions that led to the Civil War Gordon S. Wood, New Republic

- The private intellectual Tobi Haslett, New Yorker

- Christian humanism: A path not taken Paul Seaton, Law & Liberty

Year: 2018

Afternoon Tea: “Highland Chiefs and Regional Networks in Mainland Southeast Asia: Mien Perspectives”

This article is centered on the life story of a Mien upland leader in Laos and later in the kingdom of Nan that subsequently was made a province of Thailand. The story was recorded in 1972 but primarily describes events during 1870–1930. The aim of this article is to call attention to long-standing networks of highland-lowland relations where social life was unstable but always and persistently inclusive and multiethnic. The centrality of interethnic hill-valley networks in this Mien case has numerous parallels in studies of Rmeet, Phunoy, Karen, Khmu, Ta’ang, and others in mainland Southeast Asia and adjacent southern China. The implications of the Mien case support an analytical shift from ethnography to ethnology—from the study of singular ethnic groups that are viewed as somehow separate from one another and from lowland polities, and toward a study of patterns and variations in social networks that transcend ethnic labels and are of considerable historical and analytical importance. The shift toward ethnology brings questions regarding the state/non-state binary that was largely taken for granted in studies of tribal peoples as inherently stateless.

This is from Hjorleifur Jonsson, an anthropologist at Arizona State University’s School of Human Evolution and Social Change. Here is a link.

Nightcap

- Making sense of Japan’s new immigration policy Emese Schwarcz, Diplomat

- Deportations with benefits Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Democracy as an information system Henry Farrell, Crooked Timber

- Against debate Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

Nightcap

- Ethnicity and Philosophy Nick Nielsen, Grand Strategy Annex

- Revisiting the Dyson Sphere Caleb Scharf, Life, Unbounded

- Reading VS Naipaul Branko Milanovic, globalinequality

- Deep Learning and Abstract Orders Federico Sosa Valle, NOL

Afternoon Tea: “Dividing Power in the First and Second British Empires: Revisiting Durham’s Imperial Constitution”

In his Report on the Affairs of British North America, Lord Durham proposed that “internal” government be placed in the hands of the colonists themselves and that a short list of subjects be reserved for Imperial control. Janet Ajzenstat maintains that Durham did not intend to formally restrict the authority of the new colonial legislature by dividing power. This paper argues otherwise: that Durham’s recommendation fell squarely within a tradition of distinguishing between the internal and external affairs of the colony. This was the imprecise but pragmatic distinction that American colonists invoked during the Stamp Act crisis as a means of curtailing imperial authority over internal taxation while maintaining their allegiance to the British Crown. It also was a division that Charles Buller relied upon in a constitution for New South Wales that he proposed prior to sailing to Canada as Durham’s principal secretary. Durham likely was drawing upon this tradition when he made his recommendation, a distinction that began to crumble away almost immediately. In the result, Canadians inherited a robust semblance of self-government, just as colonists during the Stamp Act crisis had desired, but without the need for revolution.

This is from David Schneiderman, a law professor at the University of Toronto. Here is the link.

Nightcap

- Who is Joe Epstein? Jonathan Leaf, Modern Age

- “Company-style” paintings from 19th century Burma Jonathan Saha, Colonizing Animals

- Nazis: A Modern Field Guide Jonathan Kay, Quillette

- The Dangers of Letting Someone Else Decide Jonathan Klick, Cato Unbound

The Shelf Life of the Self: Arendt on Identity Politics

Demands for separating one’s public and private identities are neither new nor simple. As the argument goes, many a political philosopher have claimed that to engage in worthwhile and productive politics, we must shed our private identities to better see, so to speak, the concerns that need a more universal outlook. Thus, to better communicate and deliberate upon political questions within a polity, say a nation, the citizens need to view themselves as citizens alone sans any group affiliation based on gender, religion, race and caste. This is not to snub the importance of social identities in general but only in so far as they affect our political judgement. On the other hand, the response to such a proposal has predictably highlighted the benefits, both political and moral, that one’s private identity has on their political participation. After all, the walls between the identities are not quite as impervious to each other as the philosophers are making it to be. Our individual selves are more than just a simple addition of our social, cultural and personal experiences. How we think about political dilemmas is often and quite rightly influenced by what we anticipate from a rival social group. A female advocating the freedom to make reproductive choices is not just assessing the positions of the stakeholders involved, as Arendt’s call for ‘enlarged mentality’ would require of her. The said female also has to keep in mind the gender hierarchies at play around her.

Arendt was famously non-feminist. She believed that the transposition of the private and the social identities into our political identities can destroy the very fabric of political communication and thus, political judgement. To resolve political dilemmas facing our society, Arendt believed we needed the exact opposite of what identity politics has to offer. Our private and social selves come with a shelf life. They end where the political begins. According to Arendt, the politicization of personal and social identities brings to the fore a self-defined and accepted discrimination that takes us away from the equality that politics demands of us. To think representatively, we need to not only be treated as but also feel like political equals.

While identity politics does well to highlight a history of suppression, it also contributes to a further strengthening of political cleavages that prevent us from ever going back to the ideal state that was disturbed by the suppression. Identity politics causes harm to inter-sectionalities because it forces us to choose between conflicting identities. But more importantly, it conflates the many dimensions of our self with the identity that we have thus chosen to speak through, politically. This conflation results in a demonization of everything that does not conform to our sense of identity, resulting in a fear of the unknown (of which Martha Nussbaum has talked about in the Monarchy of Fear). In the creation of this battleground, we forget that the other side is human. Just like us. And it is easy to not think about our moral obligations to each other when the enemy has been dehumanized and reduced to a label.

Arendt on identity politics deserves much greater scrutiny. Especially because of the overwhelming reliance of social cleavages but current political leaders. The era of identity politics has given us a society with walls that mask themselves as political ideologies but are nothing more than a refusal to recognize that the other side is human too. An essential step in Arendtian judgement is to accept the inherent and equal worth of each individual, irrespective of their social identity. We would do well to find common grounds in our humanity, first.

Innovation and the Failure of the Great Man Theory

We tend to think about innovation as inventions and particularly about the inventors associated with them: Newton, Edison, Jobs, Archimedes, Watt, Arkwright. This Great Man Theory of incredible technical innovation is mostly implicitly held by quite a few of us, celebrating these great men and their deeds.

Matt Ridley, the author of The Rational Optimist and The Evolution of Everything among other credentials, has spent a lot of time and effort in recent years arguing against this theory. In his recent Hayek Lecture to the British Institute of Economic Affairs he convincingly outlines his case: so many independent innovations take place roughly at the same time by different people. The Great Man Theory leads us to believe that hadn’t it been for Edison, we’ll all be in the dark and humanity deprived ofall the benefits that came with the innovation.

Not so. There were a great number of contemporary inventors who came upon versions of the lightbulb (Ridley cites 21 or 23 or them, depending on whom you include) around the same time as Edison. The story can be repeated for most other great inventions we know of: laws of thermodynamics, calculus, most metals, typewriting machines, jet engines, the ATM, Oxygen. Indeed, the phenomenon is so common that it has its own term: simultaneous invention.

It seems, in complete contrast to the Great Man Theory, that history provided a certain problem, a sufficient number of people working on solving it at a certain time, and eventually similar inventions taking place around the same time. The process is, Ridley concludes, “gradual, incremental, collective yet inescapable inevitable […] it was bound to happen when it did”.

Interestingly enough for those of us schooled and fascinated by spontaneous orders and bottom-up social and economic phenomena, the Great Man Theory is remarkably similar to other beliefs about the world. It is a symptom of the same reasoned short-comings that makes us humans susceptible to believing in zero-sum thinking, top-down organizing and “design-implies-a-designer”. Instead of grasping the deep insights of gains from trade, spontaneous order or evolution, we are tempted by the militaristically directed organizations that we believe we understand rather than the emergent order of many independently acting individuals’ trials and errors.

Precisely this bias makes us susceptible to the mistake Mariana Mazzucato has become famous for wholeheartedly embracing: the idea that, whatever the innovation, government probably did it. That government innovation is productive – or at least more productive than is commonly presumed – and indeed societies can greatly benefit from ramping up government R&D spending. Nevermind incentives, track records or statistical robustness.

Indeed, what Ridley points to is precisely that valuable and life-changing innovation cannot be directed. Admittedly, some innovation does occur in labs, but only a vanishingly small part. Mazzucato and other top-downers could have benefited greatly from listening to Ridley (or reading his book The Rational Optimist; or reading Demsetz’ devastating 1969 article ‘Information and Efficiency’).

Coming full circle and espousing the Hayekian insights, Ridley notes that the price is everything. Specifically the reduction in prices is what matters for innovations to be spread and adopted rather than the ideas themselves. Very little happens in terms of adoption and transmission until prices start to fall dramatically (hint, hint, Bitcoin… or nuclear energy, or renewable energy…). Like the printing press and the steam engine, interesting things start to happen when prices fall – not because an innovation is particularly cool in some subsection of society.

Innovation is a deeply decentralized yet deeply collective process. We face similar challenges that occassionally come to similar conclusions – and history would in all likelihood have progress exactly the same had we not had a Newton or Edison or Jobs.

Nightcap

- Conservatives, sex, and the aspirations of women Rachel Lu, Law & Liberty

- Hello Mars, farewell Mars Caleb Scharf, Life, Unbounded

- Terrorism justified: a response to Vicente Medina (Machiavelli) Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- The third gender of southern Mexico Ola Synowiec, BBC

Afternoon Tea: “Magna Carta for the World? The Merchants’ Chapter and Foreign Capital in the Early American Republic”

This Article examines the early modern revival and subtle transformation in what is here called the merchants’ chapter of Magna Carta and then analyzes how lawyers, judges, and government officeholders invoked it in the new American federal courts and in debates over congressional power. In the U.S. Supreme Court in the early 1790s, a British creditor and an American State debated the meaning and applicability of the merchants’ chapter, which guaranteed two rights to foreign merchants: free entry and exit during peacetime, without being subjected to arbitrary taxes; and, in wartime, the promise that their persons and goods would not be harmed or confiscated, unless their own king attacked and confiscated English merchants. In other words, no harm to enemy aliens, except as retaliation. Tit for tat.

The idea that reciprocity was a fundamental mechanism of international (and interpersonal) relations became something like a social science axiom in the early modern Enlightenment. Edward Coke claimed to find that mechanism in the merchants’ chapter and publicized it to lawyers throughout the emerging British Empire and beyond. Montesquieu lauded the English for protecting foreign commerce in their fundamental law, and Blackstone basked in that praise. American lawyers derived their understanding of the merchants’ chapter from these sources and then, in the early Republic, stretched the principle behind it to protect foreign capital, not just resident merchants. The vindication of old imperial debt contracts would signal to all international creditors that, in the United States, credit was safe. Federalists then invoked the chapter outside of the courts to resist Republican attempts to embargo commerce and sequester foreign credit. For Republicans, doux commerce had become the Achilles heel of the great Atlantic empires: their reliance on American trade could be used to gain diplomatic leverage without risking war. For Federalists, economic sanctions threatened not just their fiscal policy but their entire vision of an Atlantic world that increasingly insulated international capital from national politics. They all agreed, however, that the role of foreign capital in the American constitutional system was a central issue for the new and developing nation.

This is from Daniel J. Hulsebosch, a historian at NYU’s law school. Here is the link.

Nightcap

- The passion for a kind of justice born of righteous rage Waller Newell, Claremont Review of Books

- Zbigniew Brzezinski’s Cold War: Less Than Grand Strategy Andrew Bacevich, the Nation

- No, Sex Wasn’t Better for Women Under Socialism Cathy Young, Reason

- I am Ashurbanipal, king of the world, king of Assyria Samuel Reilly, 1843

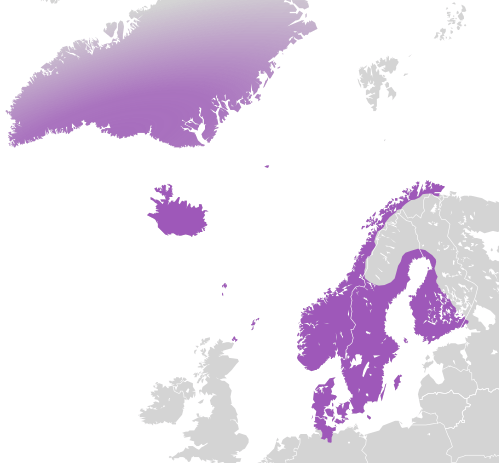

Eye Candy: Kalmar Union, circa 1400

The Kalmar Union lasted from 1397 to 1523. Here is a wiki on it. Imagine Denmark, Norway, and Sweden united as a single country when it came to foreign affairs, but each of them having plenty of room to govern themselves domestically. The main rivalry here was the “monarchy” of Kalmar and the aristocracies of both Sweden and Denmark. This domestic rivalry, coupled with fact that its neighborhood included the Holy Roman Empire and the Hanseatic League, means that the Kalmar Union is probably one of the more interesting polities in European history. Yet I know next to nothing about it…

Used in classrooms, abused in chatrooms

My God, it’s the end of November. This blog was founded at the beginning of January in 2012. When I started this consortium I just wanted to band together libertarians who already blogged but who didn’t have a large following. I thought that maybe if I could band them together something would come about. I also thought that the San Francisco Bay Area had plenty of smaller voices in the libertarian movement, so I tried to invite people from that part of the world, in the hopes that NOL could be some kind of counterweight to Mises down south and Mercatus back east.

Both efforts obviously failed spectacularly, which is not necessarily a bad thing.

Today, NOL is used in classrooms and abused in chatrooms.

I have been reading much more than writing lately. I have one child running around the flat and another on the way (due date is Jan 14th!). I have been making a rather rough sociocultural transition from city life to suburban/rural life. My wife is working towards her CPA license. I’m working a shitty job, writing for RealClearHistory, blogging here, and shoring up future articles for future academic publication. Some people are ready to write me off as a scholar, but that is foolish of them.

I’ve got something up my sleeve for NOL in 2019, too, but I’m keeping it close to my chest for now. It’s nothing crazy, so don’t go anywhere. Just know that NOL is committed to experimentation and evolution as much as it is to human freedom.

Nightcap

- Israel’s political balagan Michael Koplow, Ottomans & Zionists

- A summary of the rights of British America Thomas Jefferson, Avalon Project

- Studying Singapore before it was famous Frank Beyer, Asian Review of Books

- The mystic life of Hermann Hesse Philip Hensher, Spectator

Nightcap

- No easy road: easements and occupation in the West Bank Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Clouds over the Pacific: War, Stagnation, and the end of the Asian Century James Holmes, National Review

- Was philosophy founded by non-Western women? Dag Herbjørnsrud, Aeon

- Natural History of a Cherry Tree Nick Nielsen, Grand Strategy Annex