- Who’s who in Hamburg’s G20 protests

- “But, if Marxism is not inevitable, it is nothing. Ronald Reagan, with his abiding fear that the Evil Empire would spread without intervention, was, in this sense, a much better Marxist than David Roediger could ever hope to be.“

- It’s business as usual between Turkey and the EU

- “So far there is not much sign of the fresh dawn that IS’s downfall should bring.“

- Hell Makes the News

Year: 2017

Minimum Wages: Where to Look for Evidence (A Reply)

Yesterday, here at Notes on Liberty, Nicolas Cachanosky blogged about the minimum wage. His point was fairly simple: criticisms against certain research designs that use limited sample can be economically irrelevant.

To put you in context, he was blogging about one of the criticisms made of the Seattle minimum wage study produced by researchers at the University of Washington, namely that the sample was limited to “small” employers. This criticism, Nicolas argues, is irrelevant since the researchers were looking for those who were likely to be the most heavily affected by the minimum wage increase since it will be among the least efficient firms that the effects will be heavily concentrated. In other words, what is the point of looking at Costco or Walmart who are more likely to survive than Uncle Joe’s store? As such, this is Nicolas’ point in defense of the study.

I disagree with Nicolas here and this is because I agree with him (I know, it sounds confused but bear with me).

The reason is simple: firms react differently to the same shock. Costs are costs, productivity is productivity, but the constraints are never exactly the same. For example, if I am a small employer and the minimum wage is increased 15%, why would I fire one of my two employees to adjust? If that was my reaction to the minimum wage, I would sacrifice 33% of my output for a 15% increase in wages which compose the majority but not the totality of my costs. Using that margin of adjustment would be insensible for me given the constraint of my firm’s size. I might be more tempted to cut hours, cut benefits, cut quality, substitute between workers, raise prices (depending on the elasticity of the demand for my services). However, if I am a large firm of 10,000 employees, sacking one worker is an easy margin to adjust on since I am not constrained as much as the small firm. In that situation, a large firm might be tempted to adjust on that margin rather than cut quality or raise prices. Basically, firms respond to higher labor costs (not accompanied by greater productivity) in different ways.

By concentrating on small firms, the authors of the Seattle study were concentrating on a group that had, probably, a more homogeneous set of constraints and responses. In their case, they were looking at hours worked. Had they blended in the larger firms, they would have looked for an adjustment on the part of firms less to adjust by compressing hours but rather by compressing the workforce.

This is why the UW study is so interesting in terms of research design: it focused like a laser on one adjustment channel in the group most likely to respond in that manner. If one reads attentively that paper, it is clear that this is the aim of the authors – to better document this element of the minimum wage literature. If one seeks to exhaustively measure what were the costs of the policy, one would need a much wider research design to reflect the wide array of adjustments available to employers (and workers).

In short, Nicolas is right that research designs matter, but he is wrong in that the criticism of the UW study is really an instance of pro-minimum wage hike pundits bringing the hockey puck in their own net!

Minimum Wages: Where to Look for Evidence

A recent study on the effect of minimum wages in the city of Seattle has produced some conflicted reactions. As most economists expected, the significant increase in the minimum wage resulted in job losses and bankruptcies. Others, however, doubt the validity of the results given that the sample may be incomplete.

In this post I want to focus just one empirical problem. An incomplete sample in itself may not be a problem. The issue is whether or not the observations missing from the sample are relevant. This problem has been pointed out before as the Russian Roulette Effect, which consists in asking survivors of the increase in minimum wages if the increase in minimum wages have put them out of business. Of course, the answer is no. In regards to Seattle, a concern might be that fast food chains such as McDonald’s are not properly included in the study.

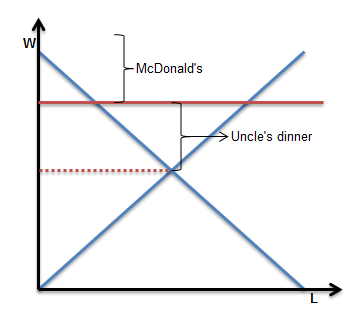

The first reaction is, so what? Why is that a problem? If the issue is to show that an increase of wages above their equilibrium level is going to produce unemployment, all that has to be shown is that this actually happens, not to show where it does not happen. This concern about the Seattle study is missing a key point of the economic analysis of minimum wages. The prediction is that jobs will be lost first among less efficient workers and less efficient employers, not equally across all workers and employers. More efficient employers may be able to absorb a larger share of the wage increase, to cut compensations, delay the lay-offs, etc. This is seen by the fact that demand is downward sloping and that a minimum wage above its equilibrium level “cuts” demand in two. Some employers are below the minimum wage (the less efficient ones) and others are above the minimum wage (the more efficient ones.) Let’s call the former “Uncle’s diner” and the latter “McDonald’s.” This how it is seen in a demand and supply graph:

Surely, there is some overlapping. But the point that this graph is making is that looking at the effects minimum wage above the red line is looking at the wrong place. A study that is looking for the effect on employment needs to be looking at what happens with below the red line. This sample, of course, has less information available than fast food chains such as McDonald’s; this is a reason why some studies focus on what can be seen even if the effect happens in what cannot be seen (and this is a value added of the Seattle study.)

This is why it is important to ask: “what do minimum wage advocates expect to find by increasing the sample size?” To question that minimum wages increase unemployment, then the critics also needs to focus on the “Uncle’s diner” part of the demand curve. If the objective is to inquire about something else, than that has no bearing on the fact that minimum wage increases do produce unemployment in the minimum wage market and at the less efficient (and harder to gather data) portion of it first.

PS: I have a previous post on minimum wages that can be found here.

More simple economic truths I wish more people understood

There are only four ways to spend money:

- You spend your money with yourself.

- You spend your money with others.

- You spend other’s money with yourself.

- You spend other’s money with others.

Just think about it for one second and you will agree: these are the only possible ways to spend money.

The best way to spend money is to spend your money with yourself. The worst is when you spend other’s money with others.

When you spend your money with yourself, you know how much money you have and what your needs are.

When you spend your money with others, you know how much money you have but you don’t know as well what other’s needs are.

When you spend other’s money with yourself you know your needs but you don’t know how much money you can actually spend. In a situation like this, some people will shy away from spending much money (when they actually could) and will end up not totally satisfied. Other people will have no problem like that and will spend as crazy, not noticing that they are spending too much. It doesn’t matter what kind of person you are: the fact is that this is not a good way to spend money.

When you spend other’s money with others you have the worst case scenario: you don’t know other’s needs as well as they know and you also don’t have a clear grasp of how much money you can actually spend.

In a true liberal capitalist society, the majority of the money is spent by individuals on their own needs. The more a society drifts away from this ideal, the more people spend money that is not actually theirs on other people. The more money is misused.

The government basically spend money is not theirs on other people. That’s why government spending is usually bad. Even the most well-meaning government official, more in line with your personal beliefs, will probably not spend your money as well as you could yourself.

Rent-Seeking Rebels of 1776

Since yesterday was Independence Day, I thought I should share a recent piece of research I made available. A few months ago, I completed a working paper which has now been accepted as a book chapter regarding public choice theory insights for American economic history (of which I talked about before). That paper simply argued that the American Revolutionary War that led to independence partly resulted from strings of rent-seeking actions (disclaimer: the title of the blog post was chosen to attract attention).

The first element of that string is that the Americans were given a relatively high level of autonomy over their own affairs. However, that autonomy did not come with full financial responsibility. In fact, the American colonists were still net beneficiaries of imperial finance. As the long period of peace that lasted from 1713 to 1740 ended, the British started to spend increasingly larger sums for the defense of the colonies. This meant that the British were technically inciting (by subsidizing the defense) the colonists to take aggressive measures that may benefit them (i.e. raid instead of trade). Indeed, the benefits of any land seizure by conflict would large fall in their lap while the British ended up with the bill.

The second element is the French colony of Acadia (in modern day Nova Scotia and New Brunswick). I say “French”, but it wasn’t really under French rule. Until 1713, it was nominally under French rule but the colony of a few thousands was in effect a “stateless” society since the reach of the French state was non-existent (most of the colonial administration that took place in French North America was in the colony of Quebec). In any case, the French government cared very little for that colony. After 1713, it became a British colony but again the rule was nominal and the British tolerated a conditional oath of loyalty (which was basically an oath of neutrality speaking to the limited ability of the crown to enforce its desires in the colony). However, it was probably one of the most prosperous colonies of the French crown and one where – and this is admitted by historians – the colonists were on the friendliest of terms with the Native Indians. Complex trading networks emerged which allowed the Acadians to acquire land rights from the native tribes in exchange for agricultural goods which would be harvested thanks to sophisticated irrigation systems. These lands were incredibly rich and they caught the attention of American colonists who wanted to expel the French colonists who, to top it off, were friendly with the natives. This led to a drive to actually deport them. When deportation occurred in 1755 (half the French population was deported), the lands were largely seized by American settlers and British settlers in Nova Scotia. They got all the benefits. However, the crown paid for the military expenses (they were considerable) and it was done against the wishes of the imperial government as an initiative of the local governments of Massachusetts and Nova Scotia. This was clearly a rent-seeking action.

The third link is that in England, the governing coalitions included government creditors who had a strong incentives to control government spending especially given the constraints imposed by debt-financing the intermittent war with the French. These creditors saw the combination of local autonomy and the lack of financial responsibility for that autonomy as a call to centralize management of the empire and avoid such problems in the future. This drive towards centralization was a key factor, according to historians like J.P. Greene, in the initiation of the revolution. It was also a result of rent-seeking on the part of actors in England to protect their own interest.

As such, the history of the American revolution must rely in part on a public choice contribution in the form of rent-seeking which paints the revolution in a different (and less glorious) light.

Algeria: a sparse memory

In 1962, France and the Algerian nationalists came to an agreement about Algerian independence. That was after 130 years of French colonization and eight years of brutal war including war against civilians. I participated in the evacuation of large number of French civilians from the country as a little sailor. The number who wanted to leave was much greater than anyone expected. It was too bad that they left in such large numbers. It was a pity for all concerned. The events were a double tragedy or a tragedy leading to a tragedy. The Algerian independence fighters who had prevailed by shedding quantities of their blood were not (not) Islamists. In most respects, intellectually and otherwise, they were a lot like me.

The true revolutionaries were soon replaced however by professional soldiers that I think of as classical but fairly moderate fascists. I went back to Algeria six years after independence. I was warmly received and I liked the people there. People invited me to lunch; I shared with them the fish I caught and a baby camel tried to browse my hair in a cafe.

I still think the nationalists were on the right side of the argument but I miss Algeria nevertheless. It’s like a divorce that should not have happened. And I am very sorry about where French incompetence and rigidity led everyone, especially the Algerians who keep migrating to France in huge numbers because they can’t find what they need at home.

The Deleted Clause of the Declaration of Independence

As a tribute to the great events that occurred 241 years ago, I wanted to recognize the importance of the unity of purpose behind supporting liberty in all of its forms. While an unequivocal statement of natural rights and the virtues of liberty, the Declaration of Independence also came close to bringing another vital aspect of liberty to the forefront of public attention. As has been addressed in multiple fascinating podcasts (Joe Janes, Robert Olwell), a censure of slavery and George III’s connection to the slave trade was in the first draft of the Declaration.

Thomas Jefferson, a man who has been criticized as a man of inherent contradiction between his high morals and his active participation in slavery, was a major contributor to the popularizing of classical liberal principles. Many have pointed to his hypocrisy in that he owned over 180 slaves, fathered children on them, and did not free them in his will (because of his debts). Even given his personal slaves, Jefferson made his moral stance on slavery quite clear through his famous efforts toward ending the transatlantic slave trade, which exemplify early steps in securing the abolition of the repugnant act of chattel slavery in America and applying classically liberal principles toward all humans. However, this very practice may have been enacted far sooner, avoiding decades of appalling misery and its long-reaching effects, if his (hypocritical but principled) position had been adopted from the day of the USA’s first taste of political freedom.

This is the text of the deleted Declaration of Independence clause:

“He has waged cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him, captivating and carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere or to incur miserable death in their transportation thither. This piratical warfare, the opprobrium of infidel powers, is the warfare of the Christian King of Great Britain. Determined to keep open a market where Men should be bought and sold, he has prostituted his negative for suppressing every legislative attempt to prohibit or restrain this execrable commerce. And that this assemblage of horrors might want no fact of distinguished die, he is now exciting those very people to rise in arms among us, and to purchase that liberty of which he has deprived them, by murdering the people on whom he has obtruded them: thus paying off former crimes committed against the Liberties of one people, with crimes which he urges them to commit against the lives of another..”

The second Continental Congress, based on hardline votes of South Carolina and the desire to avoid alienating potential sympathizers in England, slaveholding patriots, and the harbor cities of the North that were complicit in the slave trade, dropped this vital statement of principle

The removal of the anti-slavery clause of the declaration was not the only time Jefferson’s efforts might have led to the premature end of the “peculiar institution.” Economist and cultural historian Thomas Sowell notes that Jefferson’s 1784 anti-slavery bill, which had the votes to pass but did not because of a single ill legislator’s absence from the floor, would have ended the expansion of slavery to any newly admitted states to the Union years before the Constitution’s infamous three-fifths compromise. One wonders if America would have seen a secessionist movement or Civil War, and how the economies of states from Alabama and Florida to Texas would have developed without slave labor, which in some states and counties constituted the majority.

These ideas form a core moral principle for most Americans today, but they are not hypothetical or irrelevant to modern debates about liberty. Though America and the broader Western World have brought the slavery debate to an end, the larger world has not; though countries have officially made enslavement a crime (true only since 2007), many within the highest levels of government aid and abet the practice. 30 million individuals around the world suffer under the same types of chattel slavery seen millennia ago, including in nominal US allies in the Middle East. The debates between the pursuit of non-intervention as a form of freedom and the defense of the liberty of others as a form of freedom have been consistently important since the 1800’s (or arguably earlier), and I think it is vital that these discussions continue in the public forum. I hope that this 4th of July reminds us that liberty is not just a distant concept, but a set of values that requires constant support, intellectual nurturing, and pursuit.

For more underrecognized history surrounding the founding of America, see my Before the Fourth series!

Adam Smith on the character of the American rebels

They are very weak who flatter themselves that, in the state to which things have come, our colonies will be easily conquered by force alone. The persons who now govern the resolutions of what they call their continental congress, feel in themselves at this moment a degree of importance which, perhaps, the greatest subjects in Europe scarce feel. From shopkeepers, tradesmen, and attornies, they are become statesmen and legislators, and are employed in contriving a new form of government for an extensive empire, which, they flatter themselves, will become, and which, indeed, seems very likely to become, one of the greatest and most formidable that ever was in the world. Five hundred different people, perhaps, who in different ways act immediately under the continental congress; and five hundred thousand, perhaps, who act under those five hundred, all feel in the same manner a proportionable rise in their own importance. Almost every individual of the governing party in America fills, at present in his own fancy, a station superior, not only to what he had ever filled before, but to what he had ever expected to fill; and unless some new object of ambition is presented either to him or to his leaders, if he has the ordinary spirit of a man, he will die in defence of that station.

Found here. Today, many people, especially libertarians in the US, celebrate an act of secession from an overbearing empire, but this isn’t really the case of what happened. The colonies wanted more representation in parliament, not independence. London wouldn’t listen. Adam Smith wrote on this, too, in the same book.

Smith and, frankly, the Americans rebels were all federalists as opposed to nationalists. The American rebels wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom because they were British subjects and they were culturally British. Even the non-British subjects of the American colonies felt a loyalty towards London that they did not have for their former homelands in Europe. Smith, for his part, argued that losing the colonies would be expensive but also, I am guessing, because his Scottish background showed him that being an equal part of a larger whole was beneficial for everyone involved. But London wouldn’t listen. As a result, war happened, and London lost a huge, valuable chunk of its realm to hardheadedness.

I am currently reading a book on post-war France. It’s by an American historian at New York University. It’s very good. Paris had a large overseas empire in Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Caribbean. France’s imperial subjects wanted to remain part of the empire, but they wanted equal representation in parliament. They wanted to send senators, representatives, and judges to Europe, and they wanted senators, representatives, and judges from Europe to govern in their territories. They wanted political equality – isonomia – to be the ideological underpinning of a new French republic. Alas, what the world got instead was “decolonization”: a nightmare of nationalism, ethnic cleansing, coups, autocracy, and poverty through protectionism. I’m still in the process of reading the book. It’s goal is to explain why this happened. I’ll keep you updated.

Small states, secession, and decentralization – three qualifications that layman libertarians (who are still much smarter than conservatives and “liberals”) argue are essential for peace and prosperity – are worthless without some major qualifications. Interconnectedness matters. Political representation matters. What’s more, interconnectedness and political representation in a larger body politic are often better for individual liberty than smallness, secession, and so-called decentralization. Equality matters, but not in the ways that we typically assume.

Here’s more on Adam Smith at NOL. Happy Fourth of July, from Texas.

The Behavioural Economics of the “Liberty & Responsibility” couple.

The marketing of Liberty is enclosed with the formula “Liberty + Responsibility.” It is some sort of “you have the right to do what you please, BUT you have to be responsible for your choices.” That is correct: the costs and profits enable rationality to our decisions. The lack of the former brings about the tragedy of the commons outcome. In a world where everyone is accountable for his choices, the ideal of liberty as absence of arbitrary coercion will be delivered by the resulting structure of rational individual decisions limiting our will.

The couple of Liberty and Responsibility is right BUT unattractive. First of all, the formula is not actually “Liberty + Responsibility,” but “Liberty as Absence of Coercion – What Responsibility Takes Away.” The latter is still right: Responsibility transforms negative liberty as “absence of coercion” into “absence of arbitrary coercion.” The problem remains a matter of marketing of ideas.

David Hume is a strong candidate for the title of “First Behavioural Economist,” since he had stated that it is more unpleasant for a man to have the unfulfilled promise of a good than not having neither the good nor the promise of it. The latter might be a desire, while the former is experienced as a dispossession. The couple “Liberty – Responsibility” dishes out the same kind of deception.

It is like someone who tells to you: “do what you want, enjoy 150% of Liberty”; and suddenly, he warns you: “but wait! You know there’s no such thing as a free lunch, if you are 150% free, someone will be 50% your slave. Give that illegitimate 50% of freedom back!” And he will be -again- right: being responsible makes everybody 100% free. Right – albeit disappointing.

Perhaps we should restate the formula the other way around: “Being 100% responsible for your choices gives you the right to claim 100% of your freedom.” Only a few will be interested in being more than 100% responsible for anything. But if it happens that someone is expected to deal alone with his own needs, at least he will be entitled to claim the right to his full autonomy.

The formula of “Responsibility + Liberty” is associated with the evolutionist notion of liberties, which means rights to be conquered, one by one. Being responsible and then free means that Liberty is not an unearned income to be neutrally taxed. It is not a “state of nature” to give in exchange for civilization, but a project to grow, a goal, a raison d’etre.

Putting first Responsibility and then Liberty determines a curious outcome: you are consciously free to choose the amount of freedom you are really willing to enjoy. Markets and hierarchies are, then, not antagonistic terms, but structures of cooperation freely consented. Moreover, what we trade are not goods, not even rights on goods, but parcels of our sphere of autonomy.

Mexicans in Mexico

I just spent another two weeks in Mexico, in Puerto Vallarta to be specific, a town pretty much invented by Liz Taylor and Richard Burton. (See the movie “Night of the Iguana.”) The more time I spend in Mexico, the more I like Mexicans. I may have to repeat myself here.

Mexican cities are clean because people sweep in front of the their doors every morning without being told. Everybody there works or is seeking hard to work. Everybody is polite and friendly. One exception: an older taxi driver showed some discrete ill humor with me. I had mistakenly given him 15 cents (American) for a tip. That’s it. Every other interaction I had was gracious or better. (It’s true that my Spanish is good and that I was accompanied most of the time by my adorable 8 year-old granddaughter modeling a broad-brim straw hat.)

Every time I am in Mexico, I notice something new. This time, I was there during the summer vacation period and Mexicans from the US were numerous and very visible. They come to Mexico to kiss old grandpa and grandma, in one case, to get married, and to a large extent, for a vacation, like everyone else. They tend to be loud and better dressed than the locals. They are brisk consumers who buy their children the best beach equipment and all the tours available, like new consumers often do. Many are garrulous and strike up a conversation with strangers easily. They know their place in the sun. I may be dreaming but I think there is something distinctively American about them.

I also bumped into a surprisingly large number of “returnees for good,” including several who got stuck on the southern side of the southern border. Many more lived in the US (legally or not, we don’t often talked about that), made their pile, and took their savings and deliberately started life anew in the old country. One bought two taxis, several built houses, another acquired a ranch where some of his less urbanized relatives live and make a living. He mentioned cows, of course, but also horses. There is a whole program of upward mobility in the simple word “horses.” Unless you have a dude ranch (unknown in Mexico, I think), horses are only for recreation. Manuel, back from short-order cooking in Los Angeles, can even afford to have his children ride. All those brief Mexican acquaintances speak well of the US; they are proud of their stay in this country but they are happy to be back in Mexico for good. In 2009, my co-author Sergey Nikiforov and I had already stated about Mexican immigrants that Mexicans, by and large, would rather live in Mexico. (“If Mexicans and Americans could cross the border freely.” [pdf])

Returnees play all kinds of bridge roles where their American experience is useful. The main “client relations specialist” in my hotel was a 23 year-old guy who had been brought up (illegally) in Colorado. Of course, his English is perfect. Soon, he will open his own business, I think.

I don’t want to give the impression that the returnees’ fate is merely to serve the needs of American tourists and visitors. It seems to me that, like many bilingual people who have lived in more than one country, they are naturally cosmopolitan types who are useful in many non-domestic business situations. (I have modest qualifications to pass judgment here because I taught international business at an elementary level for 25 years. I also worked as a consultant in that field for several years.)

The average literate Mexican is an avid student of Americana. With the help of returnee relatives, he may actually excel there. Everyone below 30 in Mexico is studying English. I have said it before: in a few years, we will be begging them to come back.

Surprisingly little talk about “the wall.” Mexicans have a sense of humor. Of course, I, myself, believe that Pres. Trump will succeed. He will build a solar electricity-producing wall, sell the electricity to Mexicans at low cost (thus making them pay for the wall) and they will thank him!

Muslim Welcome

Here is a nice little story, I think.

I was once a pretend hippie. It was only “pretend” because my drug consumption was moderate and limited and I never dropped acid. Also, I never dropped out as recommended. I attended graduate school and I even worked quite a bit.

At the end of a work interlude in France from graduate school in the US, I thought I deserved a reward. (I often think I deserve a reward; it does not take much.) I was a big-time free-diver (no SCUBA) for most of my life, not so much for the beauty of it but always in search of something good to eat. I decided to leave gray Paris for a diving vacation in sunny Algeria.

It was only nine years after the end of the bloody war by which Algerians won their independence from France. Practically, the whole French population was gone. There were tensions between the French and the Algerian governments although hundreds of thousands of Algerians were working and living in France. I thought my good manners and my smiling face would get me through any difficulty. Also, I thought that with the French gone, there must have been precious little spear fishing in Algerian waters. I half-believed that big groupers would practically jump at me

I packed my VW bus I had outfitted for camping and I put a small borrowed plastic boat on its roof. My then-future ex-wife (“TFEW”) and I drove to Marseilles where we checked in bus and boat. We spent the night-long crossing of the Med on deck. There was a moving moment in the middle of the crossing when all the portable radios on board suddenly tuned them selves to Arab music from Radio Algiers. The dolphins accompanied our ship into the light blue waters of Algiers Bay.

One thing the Algerians had learned from the French and had not yet forgotten was running a non-corrupt bureaucracy. (I believe corrupt is good, that it expedites bureaucratic processes.) It took hours to clear us because the TFEW had an American passport, something unusual then and there. Clearing the bus and the boat through customs took even more time. By the time we were out of the harbor building, the sun was setting. We did not want to spend the night in some shabby overpriced hotel in the big city so, we drove on out of town in a general eastward direction.

After a couple of hours in deep-darkness, we were on a dirt road climbing some hills which made me admit that it was probably not the main coastal highway. I couldn’t see much with the weak VW headlights and there was a little mist. The torchlight I had packed was not much more useful. I ended up stopping the bus more or less at random. We stepped outside for a leak. There were not house lights, not street lights, and no sound except the song of the cicadas. We figured we might just bed down in the van till morning.

The sun was fairly high in the sky when we woke up. I saw some blue through a window of the bus. I opened the door to take out the equipment necessary for a cup of Nescafé. I discovered we were parked right in the middle of a low farmhouse courtyard. And old man in a djellaba was quietly sitting on a rock outside our door with an earthenware jar of cool water at his side and a basket of figs on his lap. “Bonjour, Salaam” he said pleasantly.

BC’s weekend reads

- Cairo’s Chinatown

- Informational post on Turkish grand strategy

- Free speech for me, but not for thee (SPLC edition)

- Experts and the gold standard and, really, a big key to continued economic development

- A bunch of new earth-like planets have been found. The Long Space Age (peep the dates)

Simple economics I wish more people understood

Economics comes from the Greek “οίκος,” meaning “household” and “νęμoμαι,” meaning “manage.” Therefore, in its more basic sense, economy means literally “rule of the house.” It applies to the way one manages the resources one has in their house.

Everyone has access to limited resources. It doesn’t matter if you are rich, poor, or middle class. Even the richest person on Earth has limited resources. Our day has only 24 hours. We only have one body. This body starts to decay very early in our lives. Even with modern medicine, we don’t get to live much more than 100 years.

The key of economics is how well we manage our limited resources. We need to make the best with the little we are given.

For most of human history, we were very poor. We had access to very limited resources, and we were not particularly good at managing them. We became much better in managing resources in the last few centuries. Today we can do much more with much less.

Value is a subjective thing. One thing has value when you think this thing has value. You may value something that I don’t.

We use money to exchange value. Money in and of itself can have no value at all. It doesn’t matter. The key of money is its ability to transmit information: I value this and I don’t value that.

Of course, many things can’t be valued in money. At least for most people. But it doesn’t change the fact that money is a very intelligent way to attribute value to things.

The economy cannot be managed centrally by a government agency. We have access to limited resources. Only we, individually, can judge which resources are more necessary for us in a given moment. Our needs can change suddenly, without notice. You can be saving money for years to buy a house, only to discover you will have to spend this money on a medical treatment. It’s sad. It’s even tragic. But it is true. If the economy is managed centrally, you have to transmit information to this central authority that your plans have changed. But if we have a great number of people changing plans every day, then this central authority will inevitably be loaded. The best judge of how to manage your resources is yourself.

We can become really rich as a society if we attribute responsibility for each person on how we manage our resources. If each one of us manages their resources to the best of their knowledge and abilities, we will have the best resource management possible. We will make the best of the limited resources we have.

Economics has a lot to do with ecology. They share the Greek “οίκος” which, again, means “household.” This planet is our house. The best way to take care of our house is to distribute individual responsibility over individual management of individual pieces of this Earth. No one can possess the whole Earth. But we can take care of tiny pieces we are given responsibility over.

Against Guilt by Historical Association: A Note on MacLean’s “Democracy in Chains”

It’s this summer’s hottest pastime for libertarian-leaning academics: finding examples of bad scholarship in Nancy MacLean’s new book Democracy in Chains. For those out of the loop, MacLean, a history professor at Duke University, argues in her book that Nobel-prize winning public choice economist James Buchanan is part of some Koch-funded vast right-libertarian conspiracy to destroy democracy as inspired by southern racist agrarians and confederates like John Calhoun. This glowing review from NPR should give you a taste of her argument, which often has the air of a bizarre conspiracy theory. Unfortunately, to make these arguments she’s had to cut some huge corners in her federally-funded research. Here’s a round-up of her dishonesty:

- David Bernstein points out how MacLean’s own sources contradict her claims that libertarian Frank Chodorov disagreed with the ruling in Brown v. Board.

- Russ Roberts reveals how out-of-context Tyler Cowen was taken by MacLean, misquoting him to attribute to Cowen a view which he was arguing against.

- David Henderson finds that she did the same thing to Buchanan.

- Steve Horwitz points out how wildly out-of-context MacLean took a quote from Buchanan on public education.

- Phil Magness reveals how much MacLean needed to wildly reach to tie Buchanan to southern agrarians with his use of the word “Leviathan.”

- Phil Magness, again, reveals MacLean needed to do the same thing to tie Buchanan to Calhoun.

- David Bernstein finds several factual errors about MacLean’s telling of the history of George Mason’s University.

I’m sure there is more to come. But, poor scholarship and complete dishonesty in source citation aside, an important question needs to be asked about all this: even if MacLean didn’t need to reach so far to paint Buchanan in such a negative light, why should we care?

I admittedly haven’t read her book yet (so could be wrong), but from the way even positive reviewers paint it and the way she talks about it herself in interviews (see around 15:30 of that episode), one can infer that she is in no way interested in a nuanced analytical critique of Buchanan’s public choice models or his arguments in favor of constitutional restrictions on democratic majorities. Her argument, if you can call it that, seems to be something like this:

- Democracy and majority rule are inherently good.

- James Buchanan wants stricter restrictions on democratic majority rule, and so did some Southern racists.

- Therefore, James Buchanan is a racist, evil corporate shill.

Even if she didn’t need to establish premise 2, why should we care? Every ideology has elements of it that can be tied to some seedy elements of the past, it doesn’t make the arguments that justify those ideologies wrong. For example, the pro-choice and women’s health movement has its roots in attempts to market birth control to race-based eugenicists (though these links, like MacLean’s attempts, aren’t as insidious as some on the modern right make them out to be), that does not mean modern women’s health advocates are racial eugenicists. Early advocates of the minimum wage argued for wage floors for racist and sexist reasons, yet nobody really thinks (or, at least, should think) modern progressives have dubious racist motives for wanting to raise the minimum wage. The American Economic Association was founded by racist eugenicists in the American Institutionalist school, yet nobody thinks modern economists are racist or that anyone influenced by the institutionalists today is a eugenicist. The Democratic Party used to be the party of the KKK, yet nobody (except the most obnoxious of Republican partisans) thinks that’s at all relevant to the DNC’s modern platform. Heidegger was heavily linked to Nazism and anti-Semitism, but it’s impossible to write off and ignore his philosophical contributions and remain intellectually honest.

Similarly, even if Buchanan did read Calhoun and it got him thinking about constitutional reform, that does not at all mean he agreed with Calhoun on slavery or that modern libertarian-leaning public choice theorists are neo-confederates, and it has even less to do with the merits of Buchanan’s analytical critiques of how real-world democracies function. In fact, as Vincent Geloso has pointed out here at NOL, Buchanan has given modern scholars the analytical tools to critique racism.

Intellectual history is messy and complicated, and can often lead to links we might—with the benefit of historical hindsight—view as situated in an unsavory context. However, as long as those historical lineages have little to no bearing on people’s motivations for making similar arguments or being intellectual inheritors of similar ideological traditions today (which isn’t always the case), there is no relevance to modern discourse other than perhaps idle historical curiosity. These types of attempts to cast guilt upon one’s intellectual opponents through historical association are, at best, another intellectually lazy version of the genetic fallacy (which MacLean also loves to commit when she starts conspiratorially complaining about Koch Brothers funding).

Just tell me if this sounds like a good argument to you:

- Historical figure X makes a similar argument Y to what you’re making.

- X was a racist and was influenced by some racists.

- Therefore, Y is wrong.

If it doesn’t, you’re right, 3 doesn’t follow from 2 (and in MacLean’s case 1 is a stretch).

Please, if you want to criticize someone’s arguments, actually criticize their arguments; don’t rely on a tabloid version of intellectual history to dismiss them, especially when that intellectual history is a bunch of dishonest misquotations and hand-waving associations.

The importance of understanding causal pathways: the case of affirmative action.

Let us put aside the question of whether affirmative action is a desirable goal. Instead I wish to ponder how to implement affirmative action, given that it will be implemented in some form regardless.

The logic of most affirmative action programs is that X vulnerable community’s outcomes (Y) are significantly below the average. For the sake of example let us say that X is Cherokees and Y is the number of professional baseball players from that ethno-racial group.

Y = f(X)

A public policy analyst who simply noted the under representation of Cherokees in the MLB, without digging deeper into the causal pathway, may propose that quotas be implemented requiring teams to have a certain share of Cherokee players. Such a proposal would be a bad one. It would be bad because it could lead to privileged Cherokees gaining spots in the MLB at the expense of less privileged individuals from other ethno-racial groups.

A better public policy analysis would note that Cherokees are less likely to enter professional baseball because they are malnourished (Z). This analyst, recognizing the causal pathway, may instead propose a program be implemented to deal with malnourished individuals regardless of their ethno-racial identity.

Y = f(X); X = f(Z)

Most affirmative action programs that I have come across are of the former type. They recognize that X ethno-racial group is performing poorly in Y outcome, and propose action without acknowledging Z. We need more programs that are designed with Z in mind.

I do not say any of this because I am an upper class white male who resents others receiving affirmative action. To the contrary. I have benefited from this type of affirmative action several times in my life. On paper I am a gold mine for a human resources worker looking to fulfill diversity quotas: I am a undocumented Hispanic of Black-Jewish descent who was raised in a low income household. I am not however vulnerable. I come from a low income household, but my Z is not low. Not really.

Despite my demographic group, I am not malnourished. I could stand to lose weight, but I am not unhealthy. I attended a state university, but my undergraduate education is comparable to that of someone who attended a public ivy. My intelligence is on the right side of the bell curve. Absent affirmative action I am confident I would achieve entry into the middle class.

Nor am I a rarity among beneficiaries. My observation is that many beneficiaries of affirmative action programs are not low on Z and left alone would achieve success on their own. Affirmative action programs are often constructed in such a way that someone low on Z could not navigate their application process. It may seem egalitarian to require applicants to submit course transcripts, to write essays, or present letters of recommendations. However these seemingly simple tasks require a level of Z that the truly under privileged do not have.

Good public policy analysis requires us to understand causal pathway of why X groups do not achieve success at similar rates as other groups. We must design programs that target undernourishment instead of simply targeting Cherokees. If we fail to do so we may have more Cherokees playing for the Dodgers, but will have failed to solve the deeper program.

Note that I say vulnerable as opposed to ‘minority’ in the above passage. This is to acknowledge that many so-called minority groups are nothing of the sort. Hispanics, Blacks, and Asians form majorities in various parts of southwest, south, and the pacific (e.g. Hawaii). Women likewise are not a minority, but are often covered by affirmative action programs. Jews are in many instances minorities, but in contemporary life are far from under represented in society’s top professions. This distinction may seem too obvious to be worth making, but it is not. Both sides of the political spectrum forget that the ultimate goal of affirmative action is to aid vulnerable individuals. Double emphasize on individuals.