from Kevin Vallier, in the latest issue of Isonomia Quarterly.

Don’t forget to check out the rest, which includes essays on Hayek, the geopolitics of Greenland, the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki, and a poem by Robert Frost.

from Kevin Vallier, in the latest issue of Isonomia Quarterly.

Don’t forget to check out the rest, which includes essays on Hayek, the geopolitics of Greenland, the nuclear bombing of Nagasaki, and a poem by Robert Frost.

Hi all,

Apologies for not blogging very much. Here’s what I’ve been working on. There is more to come!

Get your fix right here!

For those of you on Bluesky, we now are too. Feel free to give us a follow.

Note: This is the third in a series of essays on public discourse. Here’s Part 1 and Part 2

Three years ago, I started this essay series on the collapse of public discourse. At the time, I was frustrated by how left-wing and progressive spaces had become cognitively rigid, hostile, and uncharitable to any and all challenges to their orthodoxy. I still stand by most everything I said in those essays. Once you have successfully identified that your interlocutors are genuinely engaging in good faith, you must drop the soldier mindset that you are combating a barbarian who is going to destroy society and adopt a scout mindset. For discourse to serve any useful epistemic or political function, interlocutors must accept and practice something like Habermas’ rules of discourse or Grice’s maxims of discourse, where everyone is allowed to question or introduce any idea to cooperatively arrive at an intersubjective truth. The project of that previous essay was to therapeutically remind myself and any readers to actually apply and practice those rules of discourse in good-faith communication.

However, at the time, I should have more richly emphasized something that has been quite obviously true for some time now: most interlocutors in the political realm have little to no interest in discourse. I wish more people had such an interest, and still stand by the project of trying to get more people, particularly in leftist and libertarian spaces, to realize that when they speak to each other, they are not dealing with barbarian threats. However, recent events have made it clear that the real problem is figuring out when an interlocutor is worthy of having the rules of discourse applied in exchanges with them. Here is an obviously non-exhaustive list of such events in recent times that make this clear:

All these were obvious trends three years ago and have very predictably only gotten more severe. You may quibble with the extent of my assessment of any individual example above. Regardless, all but the most committed of Trumpanzees can agree that there is a time and place to become a bit dialogically illiberal in times like these. Thus, it is time to address how one can be a dialogical liberal when the barbarians truly are at the gates. The tough question to address now is this: what should the dialogical liberal do when faced with a real barbarian, and how does she know she is dealing with a barbarian?

This is an essay about how to remain a dialogical liberal when dialogical liberalism is being weaponized against you. This essay isn’t for the zealots or the trolls. It’s for those of us who believed, maybe still believe, that democracy depends on dialogue—but who are also haunted by the sense that this faith is being used against us.

Epistemically Exploitative Bullshit

I always intended to write an essay to correct the shortcomings of the original one. I regret that, for various personal reasons, I did not do so sooner. The sad truth is that a great many dialogical illiberals who are also substantively illiberal engage in esoteric communication (consciously or not). That is, their exoteric pretenses to civil, good-faith communication elide an esoteric will to domination. Sartre observed this phenomenon in the context of antisemitism, and he is worth quoting at length:

Never believe that anti‐Semites are completely unaware of the absurdity of their replies. They know that their remarks are frivolous, open to challenge. But they are amusing themselves, for it is their adversary who is obliged to use words responsibly, since he believes in words. The anti‐Semites have the right to play. They even like to play with discourse for, by giving ridiculous reasons, they discredit the seriousness of their interlocutors. They delight in acting in bad faith, since they seek not to persuade by sound argument but to intimidate and disconcert. If you press them too closely, they will abruptly fall silent, loftily indicating by some phrase that the time for argument is past. It is not that they are afraid of being convinced. They fear only to appear ridiculous or to prejudice by their embarrassment their hope of winning over some third person to their side.

If then, as we have been able to observe, the anti‐Semite is impervious to reason and to experience, it is not because his conviction is strong. Rather, his conviction is strong because he has chosen first of all to be impervious.

What Sartre says of antisemitism is true of illiberal authoritarians quite generally. Thomas Szanto has helpfully called this phenomenon “epistemically exploitative bullshit.”

One feature of epistemically exploitative bullshit that Szanto highlights is that epistemically exploitative bullshit need not be intentional. Indeed, as Sartre implies in the quote above, the ‘bad faith’ of the epistemically exploitative bullshitter involves a sort of self-deception that he may not even be consciously aware of. Indeed, most authoritarians (especially in the Trump era) are not sufficiently self-aware or intelligent enough to consciously realize that they are deceiving others about their attitude towards truth by spouting bullshit. As Henry Frankfurt observed, bullshit is different from lying in that the liar is intentionally misrepresenting the truth, but the bullshitter has no real concern for truth in the first place. Thus, many bullshiters (especially those engaged in epistemically exploitative bullshit) believe their own bullshit, often to their detriment.

However, the fact that epistemically exploitative bullshit is often unintentional, or at least not consciously intentional, creates a serious ineliminable epistemic problem for the dialogical liberal who seeks to combat it. It is quite difficult to publicly and demonstrably falsify the hypothesis that one’s interlocutor is engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit. This often causes people who, in their heart of hearts, aspire to be epistemically virtuous dialogical liberals to misidentify their interlocutors as engaging in epistemically exploitative bullshit and contemptuously dismiss them. I, for one, have been guilty of this quite a bit in recent years, and I imagine any self-reflective reader will realize they have made this mistake as well. We will return to this epistemic difficulty in the next essay in this series.

To avoid this mistake, we must continually remind ourselves that the ascription of intention is sometimes a red herring. Epistemically exploitative bullshit is not just a problem because bullshitters intentionally weaponize it to destroy liberal democracies. It is a problem because of the social and (un)dialectical function that it plays in discourse rather than its psychological status as intentional or unintentional.

It is also worth remembering at this point that it is not just fire-breathing fascists who engage in epistemically exploitative bullshit. Many non-self-aware, not consciously political, perhaps even liberal, political actors spout epistemically exploitative bullshit as well. Consider the phenomenon of property owners—both wealthy landlords and middle-class suburbanites—who appeal to “neighborhood character” and environmental concerns to weaponize government policy for the end of protecting the economic rents they receive in the form of property values. Consider the similar phenomenon of many market incumbents, from tech CEOs in AI to healthcare executives and professionals, to sports team owners, to industrial unions, to large media companies, who all weaponize various seemingly plausible (and sometimes substantively true) economic arguments to capture the state’s regulatory apparatus. Consider how sugar, tobacco, and petrochemical companies all weaponized junk science on, respectively, obesity, cigarettes, and climate change to undermine efforts to curtail their economic activity. Almost none of these people are fire-breathing fascists, and many may believe their ideological bullshit is true and tell themselves they are helping the world by advancing their arguments.

The pervasive economic phenomenon of “bootleggers and Baptists” should remind us that an unintentional form of epistemically exploitative bullshit plays a crucial role in rent seeking all across the political spectrum. This form of bullshit is particularly hard to combat precisely because it is unintentional, but its lack of intentionality in no way lessens the harmful social and (un)dialectical functions it severe.

Despite those considerations, it is still worth distinguishing between consciously intentional forms of aggressive esotericism and more unintentional versions because they must be approached very differently. Unintentional bullshitters do not see themselves as dialogically illiberal. Therefore, responding to them with aggressive rhetorical flourishes that treat them contemptuously is very unlikely to be helpful. For this reason, the general (though defeasible) presumption that any given person spouting epistemically exploitative bullshit is not an enemy that I was trying to cultivate in the second part of this essay series still stands. In the next essay, I will address how we know when this presumption has been defeated. However, for now, let us turn our attention to the forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit common today on the right. We have now seen how epistemically exploitative bullshit can appear even in technocratic, liberal settings. But that phenomenon takes on a more virulent form when fused with authoritarian intent. This is what I call aggressive esotericism.

Aggressive Esotericism

The corrosiveness of these more ‘liberal’ and technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit discussed above, while serious, pales in comparison to more bombastically authoritarian forms of it. The truly authoritarian epistemically exploitative bullshiter aims at more than amassing wealth by capturing some limited area of state policy. While he also does that, the fascist aims at the more ambitious goal of dismantling democracy and seizing the entire apparatus of the state itself.

Let us name this more dangerous form of epistemically exploitative bullshit. Let us call this aggressive esotericism and loosely define it as the phenomenon of authoritarians weaponizing the superficial trappings of democratic conversation to elide their will to dominate others. This makes the fascistic, aggressive esotericist all the more cruel, destructive, and corrosive of society’s epistemic and political institutions.

It is worth briefly commenting on my choice of the words “aggressive esotericism” for this. The word “esoteric” in the way I am using it has its roots in Straussian scholars who argue that many philosophers in the Western tradition historically did not literally mean what their discursive prose appears to say. Esoteric here does not mean “strange,” but something closer to “hidden,” in contrast to the exoteric, surface-level meaning of the text. We need not concern ourselves with the fascinating and controversial question of whether Straussians are right to esoterically read the history of Western philosophy as they do. Instead, I am applying the general idea of a distinction between the surface level and deeper meaning of a text, the sociological problem of interpreting both the words and the deeds of certain very authoritarian political actors.

I choose the word “aggressive” to contrast with what Arthur Melzer calls “protective,” “pedagogical,” or “defensive” esotericism. In Philosophy Between the Lines Melzer argues that historically, philosophers often hid a deeper layer of meaning in their great texts. In the ancient world, Melzer argues, this was in part because they feared theoretical philosophical ideas could disintegrate social order (hence the “protective esotericism”), wanted their young students to learn how to come to philosophical truths themselves (hence the “pedagogical esotericism”), or else wanted to protect themselves from authorities for ‘corrupting the youth’ (as Socrates was accused) with their heterodox ideas.

As the modern world emerged during the Enlightenment, Melzer argues esotericism continued as philosophers such as John Locke wrote hidden messages not just for defensive reasons but to help foster liberating moral progress in society, as they had a far less pessimistic view about the role of theoretical philosophy in public life (hence their “political esotericism”). Whether Melzer is correct in his reading of the history of Western political thought need not concern us now. My claim is that many authoritarians (both right-wing Fascists and left-wing authoritarian Communists) invert this liberal Enlightenment political esotericism by engaging—both in words and in deeds, both consciously and subconsciously, and both intentionally and unintentionally—in aggressive esotericism. Hiding their esoteric will to domination behind a superficial façade of ‘rational’ argumentation.

Aggressive esotericism is a subset of the epistemically exploitative bullshit. While aggressive esotericism may be more often intentional than more technocratic forms of epistemically exploitative bullshit, it is not always so. You might realize this when you reflect on heated debates you may have had during Thanksgiving dinners with your committed Trumpist family members. Nonetheless, this lack of intention doesn’t cover up the fact that their wanton wallowing in motivated reasoning, rational ignorance, and rational irrationality has the selfish effect of empowering members of their ingroup over members of their outgroup. This directly parallels how the lack of self-awareness of the technocratic rentseeker ameliorates the dispersed economic costs on society.

Aggressive Esotericism and the Paradox of Tolerance

Even if one suspects one is encountering a true fascist, one should still have the defeasible presumption that they are a good-faith interlocutor. Nonetheless, fascists perniciously abuse this meta-discursive norm. This effect has been well-known since Popper labelled it the paradox of tolerance.

The paradox of tolerance has long been abused by dialogical illiberals on both the left and the right to undermine the ideas of free speech and toleration in an open society, legal and social norms like academic freedom and free speech, and to generally weaken the presumption of good faith we have been discussing. This, however, was far from Popper’s intention. It is worth revisiting Popper’s discussion of the Paradox of Tolerance in The Open Society and Its Enemies:

Unlimited tolerance must lead to the disappearance of tolerance. If we extend unlimited tolerance even to those who are intolerant, if we are not prepared to defend a tolerant society against the onslaught of the intolerant, then the tolerant will be destroyed, and tolerance with them. In this formulation, I do not imply, for instance, that we should always suppress the utterance of intolerant philosophies; as long as we can counter them by rational argument and keep them in check by public opinion, suppression would certainly be most unwise. But we should claim the right even to suppress them, for it may easily turn out that they are not prepared to meet us on the level of rational argument, but begin by denouncing all argument; they may forbid their followers to listen to anything as deceptive as rational argument, and teach them to answer arguments by the use of their fists. We should therefore claim, in the name of tolerance, the right not to tolerate the intolerant. We should claim that any movement preaching intolerance places itself outside the law, and we should consider incitement to intolerance and persecution as criminal, exactly as we should consider incitement to murder, or to kidnapping, or as we should consider incitement to the revival of the slave trade.

His point here is not so much to sanction State censorship of fascist ideas. Instead, his point is that there are limits to what should be tolerated. To translate this to our language earlier in the essay, he is just making the banal point that our presumption of good-faith discourse is, in fact, defeasible. The “right to tolerate the intolerant” need not manifest as legal restrictions on speech or the abandonment of norms like academic freedom. This is often a bad idea, given that state and administrative censorship creates a sort of Streisand effect that fascists can exploit by whining, “Help, help, I’m being repressed.” If you gun down the fascist messenger, you guarantee that he will be made into a saint. Further, censorship will just create a backlash as those who are not yet fully-committed Machiavellian fascists become tribally polarized against the ideas of liberal democracy. Even if Popper himself might not have been as resistant to state power as I am, there are good reasons not to use state power.

Instead, our “right to tolerate the intolerant” could be realized by fostering a strong, stigmergically evolved social stigma against fascist views. Rather than censorship, this stigma should be exercised by legally tolerating the fascists who spout their aggressively esoteric bullshit even while we strongly rebuke them. Cultivating this stigma includes not just strongly rebuking the epistemically exploitative bullshit ‘arguments’ fascists make, but exercising one’s own right to free speech and free association, reporting/exposing/boycotting those, and sentimental education with those the fascists are trying to target. Sometimes, it must include defensive violence against fascists when their epistemically exploitative bullshit manifests not just in words, but acts of aggression against their enemies.

The paradox of tolerance, as Popper saw, is not a rejection of good-faith dialogue but a recognition of its vulnerability. The fascists’ most devastating move is not to shout down discourse but to simulate it: to adopt its procedural trappings while emptying it of sincerity. What I call aggressive esotericism names this phenomenon. It is the strategic abuse of our meta-discursive presumption of good faith.

Therefore, one must be very careful to guard against mission creep in pursuing this stigmergic process of cultivating stigma in defense of toleration. As Nietzsche warned, we must be guarded against the danger that we become the monsters against whom we are fighting. I hope to discuss later in this essay series how many on the left have become such monsters. For now, let us just observe that this sort of non-state-based intolerant defense of toleration does not conceptually conflict with the defeasible presumption of good faith.

In the next part of this series, I turn to the harder question: when and how can a dialogical liberal justifiably conclude that an interlocutor is no longer operating in good faith?

You can read the whole thing here.

You can read the whole thing here.

You can read the whole thing here.

Byzantium. The surprising life of a medieval empire – by Judith Herrin

In the economy chapter, apart from the often overlooked hard-ass (gold) and long-ass (700 years) of monetary stability, the author discusses some social aspects of economic life. The Byzantine elites, following on Ancient Rome’s disdain for commercial endeavors, typically opted to invest in three things: Land, administrative offices (which could confer some coin in unofficial ways), and titles in the Court.

A Byzantine celebration, as copilot imagined it. In the other versions, people were so hardcore eastern orthodox christians that even had halos.

The Court titles had fancy names and came with regular allowances. The more mundane ones had a rate of return of 2.5%- 3.0%, while the higher-ups (like Protospatharios, loosely meaning First Sword Bearer, with responsibilities that oscillated among Chief Bodyguard, Receptionist and Master of Ceremonies) reached 8.3%. Since Byzantines had also inherited Rome’s practise of capping interest rates, we know that a simple citizen could lend at a rate of 6.0% (a banker at 8.0% and a distinguised person like a Senator at 4.0%).

Re: Byzantine interest rates, from the impressive but rather dry, A History of Interest Rates – by Sidney Homer & Richard Sylla

So, it mostly did not make sense to buy a Court title, money-wise. Unless you did manage to land as the Protospatharios, so you could enter a risk-free carry trade of 2.3% and also enjoy lovely red robes with gold lining or white robes and a golden mantle (the latter attire was reserved for eunuchs). Half-joking aside, the titles were not transferable (that is, no secondary market), so you could not probably even get back the initial investment. It turns out, fancy names / clothes/ duties/ company were a major factor, after all. And secondary markets serve a purpose, at least sometimes.

A new bill, currently under public consultation, is poised to introduce quotas, yes, for music:

Greek-Language Music Quota Bill Sparks Controversy (BalkanInsight)

In its proposed form, the bill tinkers with the music lists aired in common areas (lobbies, elevators, corridors etc) of various premises (hotels, traveling facilities, casinos and shopping malls). The programs should consist of a minimum of 45% of either Greek-language songs, or instrumental versions of said songs. The quota leaves out cafes, restaurants and such (thus slinking away from a direct breach of private economic liberty, as interventions like anti-smoking laws in some cases were found as too heavy-handed). The bill also incentivises radio stations to scale up, so to say, the play-time of this kind of songs, by allocating them more advertising time (another thing that is also strictly regulated, obviously), if they comply to some percentage. Finally, there are some provisions regarding soundtracks in Greek movie productions.

There is an international angle in this protectionist instrument (pun intended). Wiki reveals that a handful of countries apply some form or another of music quotas, with France the most prominent among them. The Greek minister also mentioned Australia and Canada in an interview.

The bill aims to protect local music legacy and invigorate modern production, as part of the competent Ministry’s constitutional mandate. But there are some discords, apart from the always funny administrative percentages (and the paraphernalia needed to track who plays what and for how much). What is deemed as eligible Greek music, in the bill’s proverbial ears, misses a tone or two: Foreign-language songs and prototype instrumental compositions, by Greek artists, do not qualify. For example, Greek band VoIC (their latest album’s cover above, source) mix rock with (mostly Greek) folk music, but fall short of the criteria. And given some minister remarks on “Englishisation”, this will be a point of contention.

Bonus tracks:

Friedrich Hayek’s main thesis in “The Road to Serfdom” (1944) consists of postulating that attempts at central planning and dirigisme provoke, through the increasing use of political expediency, a continuous erosion of the political institutions that characterize to democracy and the separation of powers, thus leaving aside, by way of exception, constitutional rules and procedures. Hayek had warned that such a process had occurred in the Weimar Republic and pointed out that England could incur a similar process if it chose dirigisme as an instrument to overcome the post-war crisis.

Hayek himself recalled in various interviews and articles that the message of his book was rarely interpreted with due accuracy, and that, consequently, statements were attributed to him that he had never made, thus blurring the authentic gist of the work. However, this does not prevent “The Road to Serfdom” from being a classic, since, as such, it offers diverse insights as times and geographies vary, to be applied to the analysis of current events or history.

Regarding this last point, it is worth saying that the processes initiated by Argentina in 1946 -whose consequences persist to this day- and by Venezuela in 1998 -still in development today- present traits that make them different from other historical examples of how a country might take a road to serfdom. Throughout the 20th century, it was possible to verify that both the cases of dirigisme in democratic nations and the advent of totalitarian and authoritarian regimes followed profound economic crises, which were in turn consequences, directly or indirectly, of the two World Wars. On the other hand, the aforementioned experiences of Argentina and Venezuela began in quite different scenarios.

But the aim here is not to identify the historical cause of a social and political event, but only to describe a series of circumstances that condition the particular form of manifestation of a phenomenon that is essentially the same: that of dirigisme and the attempt to configure economic central planning. In most of the cases that occurred throughout the 20th century -outside of those mentioned in Argentina and Venezuela- those in charge of implementing dirigiste policies found themselves with devastated economies and societies dismantled by wars. In these situations, both economic dirigisme and the attempts at central planning of the economy acted provisionally -although in a mistaken and deficient way- as organizing principles of social and economic arrangements that were already chaotic, such as the interwar period and the first years of the postwar period. Subsequently, when in the 1970s it became evident that both economic dirigisme and central planning of the economy were yielding increasing negative net results, the different countries, whether capitalist or socialist, sought their respective ways to liberalize and decentralize their economies, which led to the economic and political processes of the 1980s and 1990s.

On the other hand, the case of Argentina in 1946, as stated, was very different. Argentina had not participated in the war and its economy was robust, despite the difficulties inherent to the international context. Similarly, Venezuela in 1998, despite having a highly discredited political class, had a prosperous economy for decades, in a very favorable international context. In these countries, economic dirigisme sought to be implemented in situations in which civil society was well structured and the private sector economic system was fully operational. Therefore, it is important to point out that both processes of increased government interference in the social and economic life of both countries were accompanied by a fracture in civil society and a growing antagonism and belligerence among different social sectors, promoted from the political system itself.

Several years after “The Road to Serfdom” (1944) was published, Hayek stated in “Rules and Order” (1973) – the first volume of “Law, Legislation and Liberty” – that a legal and political order based on respect for individual freedoms was characterized by functioning as a negative feedback system: each divergence, each conflict, each imbalance, is endogenously redirected by the legal system itself in order to maintain peace between the interactions of the different individuals with each other, defining and redefining through the judicial system -which is characterized by settling intersubjective controversies, specifying the content of the law for each specific case- the limits of the respective spheres of individual autonomy. This is how a rules-based system works, as opposed to a regime in which most decisions regarding the limits of individual freedoms are made at the discretion of government authorities.

Given that the 20th century mostly offered examples of societies devastated by war, pending reconstruction, perhaps we have lost sight of the effects of economic dirigisme and attempts at central planning of the economy on Nealthy civil societies and fully functioning economies. The cases of the processes initiated by Argentina in 1946 and by Venezuela in 1998 call to think about what their consequences could be for societies with economies with a moderately satisfactory performance. Among these consequences, there will surely be a growing social polarization, in which the different sectors demand their respective participation in the discretionary redistribution of income. These situations therefore acquire the dynamics inherent to positive feedback systems, in which social belligerence escalates and demands increasing levels of government interference and authoritarianism. This is another aspect of the road to serfdom that should begin to be considered in the 21st century.

Several years ago, a mentor shared Paul Graham’s 2008 essay ‘Cities and ambition’ as part of helping me evaluate where to pursue my doctorate. Graham’s argument is that cities act like a peer group on an individual: where one lives affects one’s goals, sense of individuality, and ambition. Therefore, one should choose where to live carefully, just as one should choose one’s friends carefully.

Graham pointed out that a city is not only a geographic location, an administrative area, or a convenient location. A city is a collection of individuals who form a group. Groups in turn have a culture, a mentality, a way of doing things. As Graham described it, “[O]ne of the exhilarating things about coming back to Cambridge every spring is walking through the streets at dusk, when you can see into the houses. When you walk through Palo Alto in the evening, you see nothing but the blue glow of TVs. In Cambridge [Massachusetts, the home of Harvard and MIT] you see shelves full of promising-looking books.” Following on Graham’s essay, I propose an additional metric for evaluating a city: the contents of its second-hand bookshops.

When I travel, inevitably I wash up in at least one used bookstore. Sometimes they are independent establishments, sometimes they are specialist stores focused on collectors, sometimes they’re big chains, such as Half Price Books. Like a weathervane, second-hand bookshops point to the state of a city’s intellectual and cultural life.

Big cities, such as New York, Paris, Vienna, or Washington, D.C., have a wide array of types of second-hand bookstores. Generally, one can find a suitably catholic selection: Israel Joshua Singer lives in the same space as Olivia Butler, R. F. Kuang, William Faulkner, or Kingsley Amis. At a level above or below one can find copies of old translations of the Zohar or the Buddhist sutras along with crumbling copies of the Douay-Rheims Bible. What one will probably not find are volumes of esoteric slogans with saccharine cover designs from which religious symbolism is carefully excluded, even if the books are filed under “Christianity.”

A recent visit to St. Louis, a city which despite its problems has a lovely art museum that was buzzing with activity on its free access day (every Friday), led to the requisite visit to a small, second-hand bookstore. It was a charmingly simple establishment but rich with selection. After admiring the contrast between the display of books from the “Childhood of Famous Americans” children’s series placed near Ta-Nehisi Coates’ books, I came away with several volumes of Stefan Zweig’s essays in the original German.

In contrast, a visit to the Half Price Books in a college city which hosts the flagship state university was almost futile. A single volume of Olivia Butler sat alone amongst mishmash of fantasy books. Poetry was non-existent in the poetry section, excluding a college textbook edition of excerpts of Homer. The jewel of the literature section was an incomplete paperback set of Winston Graham’s Poldark series, with covers alluding to the derivative television show. The foreign language section had no books in French, German, or Italian, excluding dictionaries and outdated textbooks, and the Japanese subdivision had only children’s books. Translations of popular manga don’t count toward foreign language credit in such establishments. A request for the writings of Epictetus turned up nothing in the system, but several cartoon books of witches’ spells were prominently displayed at the entrance of the religion and philosophy section. The young adult section overflowed with cheap vampire romances, a fitting start for what was in the more advanced reading sections. Based on the detritus of current residents’ reading, the prognosis for intellectual or cultural life is not good for this college town.

Three papers from this year’s American Economic Journal: Economic Policy deal with shocks that change people’s willingness to migrate to another location. As usual with these, I’m reporting on recent research results that readers might find interesting, but I’m not otherwise commenting.

Nian and Wang, “Go with the Politician”

In a study of crony capitalism in China: when a Chinese local leader is transferred from one prefecture to another, large firms in the old prefecture buy up 3x more land than average in the new prefecture at half the normal price. These land parcels show lower use efficiency afterwards. For the last 30 years, land sales make up 60% of local government revenue. There is no effect going the opposite direction (firms in the new prefecture buying land in the old one) and there is no effect when that politician subsequently moves to the next prefecture.

Moretti and Wilson, “Taxing Billionaires: Estate Taxes and the Geographical Location of the Ultra-Wealthy”

Following the Forbes 400 richest Americans from 1981-2017, it is clear that they are very likely to move away from states with estate taxes, particularly as they get older. They “find a sharp and economically large increase in estate tax revenues in the three years after a Forbes billionaire’s death.” Putting the two effects together, they find that it is still profitable for most states to adopt estate taxes despite some departures with a cost/benefit ratio of 0.69.

Liu, Shamdasani, and Taraz, “Climate Change and Labor Reallocation: Evidence from Six Decades of the Indian Census”

A panel fixed-effect model looking at how the climate changed decade by decade shows that fewer Indian workers move from rural to urban or ag to non-ag firms within a district, but no effect on movement between districts. They also show this comes from changes in demand patterns: higher temperatures lower rural yields and incomes, so they buy less from non-ag sectors, which reduces the demand for non-ag labor. These effects are larger in districts with fewer roads and/or less access to the formal banking sector.

A case of couleur locale

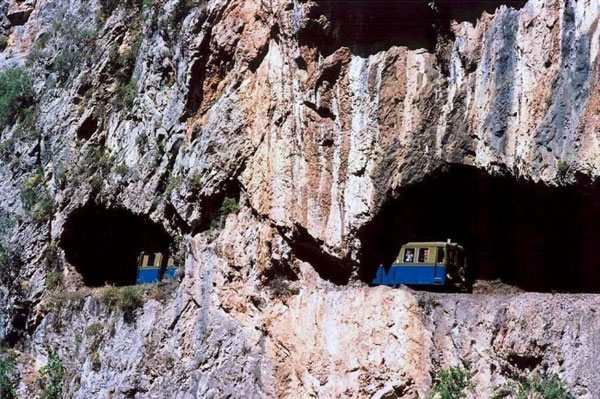

Peloponnese in Southern Greece features one of the most spectacular rack trains in the world, “Odontotos”. The short route connects a seashore town (Diakofto) with the mountainous Kalavryta plateau (700m altitude), up and through the impressive Vouraikos Gorge. Visited it for the first time recently. I kind of knew that railways were built in 1880s/90s? Something like that. The relatively young Greece acquired the large Thessalia flatland in the north at the time, putting integration via transport into perspective. Government was frantically trying to develop inter/ intra-national trade routes and at the same time bring forth a late to the party industrial mojo. Railway became a smoking symbol of this endeavor.

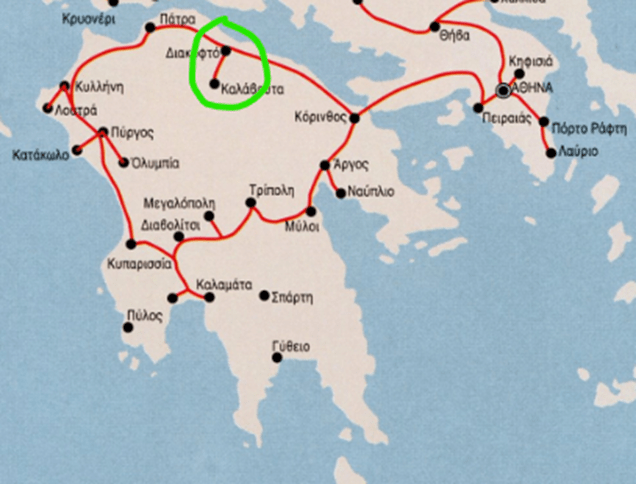

The initial expansion from Athens to the Peloponnese makes sense: Apart from the obvious pros (accessibility, speed, safety, mass character, for natives and visitors alike) of the railway, there were some major ports and established trade houses there, while agricultural production was also of note. The rails formed a curve around the northern/ western coastal line of Peloponnese and cut through its mainland in the southern/ eastern sides, in order to form a ring of sorts:

This is the 1882 plan, which mostly went through. The network was constructed in a “regular” manner, albeit with rails less wide than the international standard ‘cause cost, including cities, towns, ports and a couple of special sites (i.e., Olympia). And then we have the green-circled outcrop, the rack rail. The recent trip there left me perplexed. Why decide to undertake such a difficult task in rugged terrain, that needed expertise and special rails (different from those of the rest)?

Surely, Kalavryta was (and still is) a place of national significance. The Greek Revolution of 1821 is said to have started at a monastery (Agia Lavra) there, where the local Metropolitan blessed the gathered leaders of the upcoming war. A celebratory 1896 edition, on the occasion of the first modern Olympic Games (hosted in Athens that year), even chronicles the Peloponnese railway saga. Regarding the rack train, it references the exquisite natural environment, Agia Lavra and another historical monastery as good reasons to give it a ride. Fair enough, but still somewhat vague. What else was there that made that region stand out from the others? Here the rationale gets a step up.

Kalavryta was home to a wealthy, powerful family. It happened that a member of the family served as Member of Parliament when the railway project was on fire. This man persuaded the PM of the vital role a railway connection was to play in the development of the surrounding areas. Provided that a scion of the same family serves in the current Greek Parliament, too, this “local interest cuddling” reasoning gets some traction, in my view.

Even if the decision was just that, local patronizing, it still held some more rational economic – political water: Back then, the cost of sending wheat from the (fertile) plateau down to sea level was twice as high the cost of shipping said wheat from fucking Russia to Greece (compare 22km to, dunno, 2200km). And why not just import the dang thing then? Well, Greece had had the “honor” to be at the receiving end of a naval pacific blockade by the era’s great forces in 1886, so it perhaps had reached the conclusion that food security was something to be pursued.

The rack train project was initiated by law in 1889 and (after absorbing 3x the envisaged cost plus 5x the scheduled time of completion, effectively cutting short any ideas of expanding it further towards Tripoli) began its inaugural journey in, well, 1896.

It turns out that the whole railway affair was overhyped and demand for train services did not to really stretch that far to meet supply, not to mention the appearance of competitive means of transport (steamboats and roads). The rack train, however, remained the sole anchor of reliable transport till the 1970s, when roads proper were built. In the meantime, it also became a traveler’s sensation, too, confirming the positive light that celebratory book shone on it 120+ years before.