- Tianxia: a philosophy for world governance Salvatore Babones, Asian Review of Books

- Imperialism or federalism? Round Two Notes On Liberty

- A new history of the United States Julio Ortega, New York Times

- Postmodern politics Chris Dillow, Stumbling & Mumbling

federation

RCH: The Successful Failure of Truman Assassination Attempt

The Truman assassination attempt by Puerto Rican nationalists is the topic of my Tuesday column over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

Torresola and Collazo didn’t have much of a plan. They took a train from NYC to D.C. and approached Blair House, planning to shoot their way to Truman. Torresola walked up to the guest house and shot guard Leslie Coffelt four times at point-blank range, and Collazo started a gun fight with several guards. Torresola tried to find Collazo, leaving Coffelt for dead, but Coffelt somehow managed to get off a shot and it hit Torresola in the head, immediately killing him. Collazo was shot several times but managed to survive. It was the heaviest and longest gun fight in Secret Service history.

Please, read the rest.

NATO, Kendrick Lamar, and the answer to free riding

Edwin’s post giving one cheer to NATO brings up the old rift between European and American libertarians on foreign policy and military alliances. As usual, it’s excellent and thought-provoking. Here’s what he got out of me:

International relations splits the classical liberal/libertarian movement for a few reasons. First, consensus-building on both sides of the pond is different, and this contributes strongly to the divide over foreign policy. American libertarians lean isolationist because it aligns closer to the American left and libertarians are desperate to have some sort of common ground with American leftists. In Europe, leftists are much less liberal than American leftists (they’re socialists and communists, whereas in the States leftists are more like Millian liberals), and therefore European libertarians try to find different common ground with leftist factions. Exporting the Revolution just doesn’t do it for Europe’s libertarians.

Edwin (and Barry) have done a good job convincing me that trans-Atlantic military ties are worth the effort. But we’re still stuck at a point where the US pays too much and the Europeans do too little. Trans-Atlantic ties are deep militarily, culturally, and economically. Tariff rates between the United States and Western Europe are miniscule, and the massive military exercise put on by NATO’s heavyweights highlights well the intricate defense connections between both sides of the pond. Night clubs in Paris, London, Warsaw, and Los Angeles all play the same Kendrick Lamar songs, too.

Politically, though, the Western world is not connected enough. Sure, there are plenty of international organizations that bureaucrats on both sides of the pond are able to work in, but bureaucracy is only one aspect of getting more politically intertwined with each other (and it’s a damn poor method, too).

In 1966 economists Mancur Olson and Richard Zeckhauser wrote an article for the RAND Corporation showing that there were two ways to make NATO a more equitable military alliance: 1) greater unification or 2) sharing costs on a percentage basis. The article, titled “An Economic Theory of Alliances,” has been influential. Yet almost all of the focus since it was published over 50 years ago has been on door number 2, sharing costs on a percentage basis. Thus, you have Obama and Trump bemoaning the inability of Europe’s NATO members to meet their percentage threshold that had been agreed upon with a handshake at some sort of bureaucratic summit. You have Bush II and Clinton gently reminding Europe’s NATO members of the need to contribute more to defense spending. You have Nixon and Carter prodding Europe’s NATO members to meet an agreed-upon 3-4 percent threshold. For half a century policymakers on both sides of the Atlantic have tried to make NATO more equitable by sharing costs on a percentage basis, and it has never panned out. Ever. Sure, there have been some exceptions in some years, but that’s not okay.

What has largely been lost in the Olson & Zeckhauser article is the “greater unification” approach, probably because this is the much tougher path to take towards equitable relations. The two economists spell out what they mean by “greater unification”: replacing the alliance with a union, or federation. I’m all for this option. It would make things much more equitable and, if the Europeans simply joined the American federation, it would give hundreds of millions of people more individual freedom thanks to the compound republic the Americans have built. Edwin, along with most other European libertarians/classical liberals, acknowledges that Europe is free-riding, but are Europe’s liberals willing to cede some aspects of their country’s sovereignty in order to make the alliance more equitable? Are they ready to vote alongside Americans for an executive? Are they ready to send Senators and Representatives to Washington? Or are they just pandering to their American libertarian friends, and telling them what they want to hear so they’ll shut the hell up about being ripped off?

Nightcap

- Symmetry and Asymmetry as Elements of Federalism: A Theoretical Speculation Charles Tarlton, Journal of Politics

- The asymmetry of European integration, or why the EU cannot be a ‘social market economy’ Fritz Scharpf, Socio-Economic Review

- The past and future of European federalism: Spinelli vs. Hayek Federico Ottavio Reho, Martens Centre

- Secular Nationalism, Islamism, and Making the Arab World Luma Simms, Law & Liberty

Vox on Puerto Rican statehood

Vox, a left-wing publication founded by a fellow Bruin (Ezra Klein), has a pretty good piece up on Puerto Rico’s inability to “gain statehood,” i.e. to become a full-fledged member of the American federation. I say “pretty good” instead of great because the author, Alexia Fernández Campbell, does too much Trump-bashing and not enough focusing on the issue at hand.

Look, I didn’t vote for Trump. I don’t like Trump. But the Left’s infatuation with him is unhealthy, the way the Right’s infatuation with Obama was unhealthy. When Obama was president, I wanted so badly to rely on the right-leaning press for excellent opposition coverage of the Obama administration but, with few exceptions, all I got was garbage. The experience jaded me, and I expect less of the press, so the Left’s inability to look at the Trump administration’s many wrongdoings with clear-eyed sobriety is annoying rather than disheartening.

For instance, Campbell points out many problems facing the pro-statehood faction in Puerto Rico: a century-old racist SCOTUS ruling, the lack of a clearly-defined process for gaining statehood, anti-statehood factions in Puerto Rico, Washington’s lack of interest in adding another state, and Donald Trump being A Very Bad Man. One of these problems doesn’t fit into Puerto Rico’s decades-long campaign to gain statehood. Can you guess which one? Annoying!

At any rate, Campbell misses one of the problems facing pro-statehood factions: Puerto Rico would be a “blue” state (overseas readers: “blue state” means a reliable vote for the Democratic Party). If Puerto Rico really wants to become a member of the American federation, its policymakers would do well to start looking for a “red” state (reliable vote for the Republican Party) lobbying partner.

Nightcap

- The dark side of war propaganda Bradley Anderson, American Conservative

- Is internationalism liberal or imperialist? Arnold Kling, askblog

- Internationalism is federalist, Arnold! Brandon Christensen, NOL

- ISIS and Sykes-Picot Nick Nielsen, The View from Oregon

RCH: “10 Places That Should Join the U.S.”

That’s the title of my weekend article over at RealClearHistory. An excerpt:

9. Puerto Rico. Officially an unincorporated territory of the United States, Puerto Rico was acquired by Washington, along with Cuba and the Philippines, in the course of the Spanish-American War of 1898. Not quite an annexed state and not quite a colony, the island has been in legal limbo since the war with Spain ended. In 2017, a referendum was held on the issue of statehood (the fifth of its kind since 1952), and an overwhelming majority of those who voted preferred statehood to independence or the status quo.

Unfortunately, “those who voted” only accounted for about 23% of the island’s population, and referendum was popularly-held, meaning that the legislature didn’t vote on the matter (which is what the federal congress would require in order to consider a Puerto Rican application). Despite the odds being stacked against a Spanish-speaking state, there has never been a better time than now to join the union, especially if representatives could work in tandem with representatives of Jefferson. The history of American statehood is one of balance in the Senate. If Maine could join as a free state, then Missouri could join as a slave state. If Hawaii could join as a blue state, then Alaska could join as a red state. If Puerto Rico joined the union it would be as a blue state, and Jefferson could be the red yang to San Juan’s yin.

Nightcap

- How cotton unraveled the Chinese patriarchy Melanie Meng Xue, Aeon

- Trump, conservatives, and human rights Seth Kaplan, American Affairs

- On paper, federations generally seem like a good idea Emiliano Travieso, Decompressing History

- Switzerland’s mysterious fourth language Dena Roché, BBC

Nightcap

- The underbelly of state capacity Bryan Caplan, EconLog

- Realities and uncertainties of American Empire AG Hopkins, Defense-In-Depth

- Emancipation and representation in 1848 Senegal Jenna Nigro, Age of Revolutions

- The Koreas are moving ahead Ramon Pacheco Pardo, the Hill

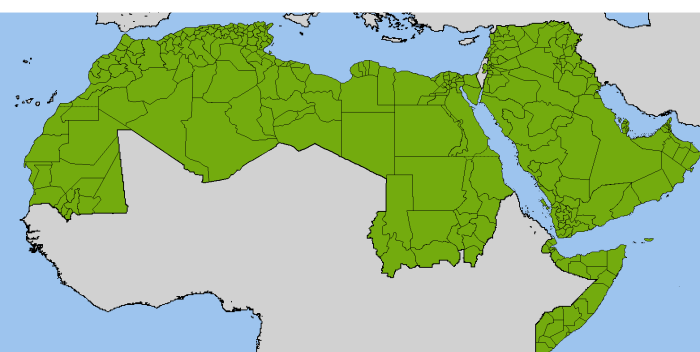

Eye Candy: the Arab world’s administrative divisions

Imagine if these divisions were all states in a federal republic. Myself, I think some of them,maybe even half of them, could be combined, but if that ever happened, and the resulting combined administrative divisions of the Arab world federated, the region would be in much better shape. (The federation of Arabia would need a Senate, of course.)

What if the OECD did the same? Or simply the US and it’s closest allies?

Nightcap

- Why French Federation Failed in Africa Tom Westland, Decompressing History

- Russia’s Centuries-Old Relationship with Kurds Pietro Shakarian, Origins

- Religious identity is once again trumping civic ties Ed West, Spectator

- The New Rise of Old Nationalism Mohsin Hamid, Guardian

Secessions that didn’t work out

No, not that secession. It’s the ten most important unsuccessful secessions of the last few decades. That’s the topic of my latest column over at RealClearHistory, anyway. An excerpt:

You already know about Catalonia and its unsuccessful bid to secede from Spain late last year. (Check out our archives if you want to get up to speed.) A comparative approach is useful here. The unsuccessful secession movements in Africa have all been violent. The unsuccessful ones in Europe and North America started out violent but have evolved into democratic movements. The key to understanding this shift is the federative structures that exist, or don’t exist, in different parts of the world. The secessionist movements in Europe and North America are not looking to go it alone any longer. These movements don’t want full sovereignty. Separatists in Europe and North America want more decision-making power in federative structures. In the case of Quebecers, it’s Canada’s unique federation; for Catalonians (and the Scottish, for that matter), it’s the European Union. Once a federative body roots itself in a region of the world, separatist tendencies cease to be violent and they shift to more peaceful forms of resistance. Kurdistan provides a microcosmic example of this evolution, In Turkey, where the Kurds continue to be ignored and oppressed, violence reigns supreme. In Iraq, where the Kurdish region has been given autonomy and self-governance, grievances are aired out in the open, in the form of non-binding referenda and in arguments put forth in a free and open press.

I also spend a good deal of time explaining why the Confederacy is no longer relevant for understanding the world we live in. Please, check it out.

Nightcap

- Revisiting Bosnia Elliot Short, War is Boring

- Liberals and conservatives are wrong on guns Rick Weber, NOL

- Why doesn’t economics progress? Arnold Kling, askblog

- The Balance of the Federation: Canada 1870 to 2016 Livio di Matteo, Worthwhile Canadian Initiative

North Korea, the status quo, and a more liberal world

The tension on the Korean Peninsula can be felt throughout the entire Pacific Rim right now. North Korea, a dictatorship with a shaky grasp on its populace, has nuclear weapons and is launching non-nuclear missiles over Japan and threatening South Korea and the United States. To make matters worse, the only state in the region that Pyongyang deems worthy of dialogue, China, refuses to engage in much multilateral work to defuse the situation.

If I were South Korea and China I would have an advanced missile shield system right on the border of North Korea, and if I were Japan I would have an advanced missile shield system spread all along my massive coastline. However, China is engaging in trade sanctions against South Korea for trying to build a missile shield along it’s border with North Korea, ostensibly because such a missile shield would threaten Beijing’s territorial integrity. This is a huge strategic mistake on China’s part. North Korea is ruled by the son of a brutal dictator who is in the midst of remaking the People’s Republic in his image. Pyongyang is launching missiles over wealthy democracies and threatening perceived enemies with nuclear annihilation. China is ignoring all of this, and undertaking policies designed to underwhelm multilateral efforts at containing North Korea because Beijing wants North Korea to serve 3 purposes: 1) a useful buffer state (but read this), 2) a hostile reminder that it considers Taiwan as part of China, and 3) as a good bargaining chip when dealing with the United States in the region.

Given that the United States is not geographically a part of East Asia, and given that Washington figures prominently in not one, not two, but all three major reasons why China refuses to engage robustly in more multilateral actions against such a destructive neighbor, we must ask ourselves: Why is the United States still in South Korea? The answer is that Koreans want them there.

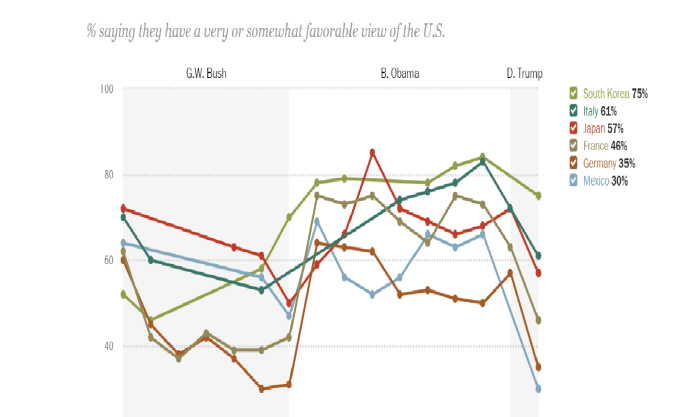

Check out the latest results of a Pew Survey asking people what they think about the United States:

75% of South Koreans have a favorable or somewhat favorable view of the US even after the election of Donald Trump. That’s higher than the other baseball-friendly countries like Italy (61%) and Japan (57%), and much higher than next-door neighbor Mexico (30%) and longtime NATO partner Germany (35%).

China is wrong to believe that an American withdrawal would suddenly make North Korea a breezy member of the international community of states. Kim Jong Un’s regime depends on foreign enemies to survive. James Madison put it best:

The means of defense against foreign danger have been always the instruments of tyranny at home. Among the Romans it was a standing maxim to excite a war whenever a revolt was apprehended. Throughout all Europe, the armies kept up under the pretext of defending have enslaved the people.

North Korea would bully Seoul and Tokyo and cajole Beijing even moreso because Washington would not be there to bear the burden of Liberal Hegemonic Boogieman.

But I’m not a Chinese citizen and this is a post about a more liberal world, so I’d like to switch gears and focus on something that all libertarians are secretly obsessed with: money.

What kind of deal is the US getting by having troops stationed along the 38th parallel? I know the US is a target of a dictator’s nuclear arsenal because of troops along the 38th, and I know the US has to expend considerable resources on the Korean Peninsula to protect Seoul, so costs are understood, but what about benefits? What about payment? What does US get in return for protecting South Korea?

Trade – a big aspect of libertarian foreign policy – is not that big of a deal for either country: the United States makes up about 14% of South Korea’s exports, and South Korea makes up nearly 3% of the United States’ exports. This means that China, for example, is a larger, more important trading partner to both countries than either is to each other.

One of the benefits I’ve found is South Korea’s participation in multilateral military actions undertaken under the umbrella of US military leadership. South Korea has provided troops for dozens of current UN missions in sub-Saharan Africa and post-British Asia, and also participated in the US-led invasions and occupations of Afghanistan and Iraq (Seoul’s troops left Iraq in 2008 and Afghanistan in 2014). I also learned that South Korea deployed 325,000 soldiers to South Vietnam from 1964-1973, losing roughly 5,100 soldiers and welcoming home another 11,000 wounded soldiers.

Seoul’s participation in Vietnam was a shocking discovery for me. It forced me to reassess America’s relationship with South Korea. The status quo is actually a decent trade-off. The status quo is cooperative, not coercive. The status quo isn’t so bad from a libertarian standpoint: There is a trade-off with mutually beneficial exchange involved, there is a cooperative rather than coercive relationship between both sides, and tens of millions of people are freer than they otherwise would be because of it.

We can still make the alliance marginally better, though. We can still take small steps to a much better world. Consider federation between the two countries.

On the face of it, such an event is ludicrously radical and completely anathema to liberty and cooperation. I would have had the same reaction just a couple of years ago, but two books have fundamentally changed my mind about this: Daniel Deudney’s Bounding Power: Republican Security Theory from the Polis to the Global Village and David Hendrickson’s Peace Pact: The Lost World of the American Founding. Both scholars are American political scientists and, as far as I can tell, card-carrying Democrats.

Deudney’s book uses theory and history to show that, among other things, republican security theory is, and always has been, from antiquity to the present day, the most important question that scholars of international relations have had to grapple with. For centuries, republics started out with the best of intentions, the best of circumstances, and always managed to decay into despotism or succumb to conquest by neighboring despots. The United States, Deudney goes on, managed to get out of this trap through federal union and, because of its peculiar geographic situation, a full-fledged republican security bargain was able to come to full fruition.

Deudney bases this part of his argument on Hendrickson’s little-known but immensely persuasive book. Hendrickson argues that the newly independent 13 states and their eventual federal union should best be viewed in an international relations framework. In order to protect themselves not only from powerful empires but more importantly from each other, the 13 states entered into a federal union that held them responsible for a limited number of shared responsibilities (such as international security and ensuring republican government in their domestic realms) and left plenty of space for each of them to exercise policymaking as they saw fit. In order to avoid a race to the bottom – where the 13 states formed security blocs between themselves and used Spain, France, and the UK to undermine their rivals – the 13 states built, piece-by-piece, a cooperative international system and called it a federation.

With America’s domestic liberties under increasing assault, largely because the current situation places so much emphasis on certain checks and balances over others, adding additional “states” in the form of South Korea’s provinces would breathe new life into all of the institutions necessary for both security and republican domestic governance.

The inevitable Korean bloc

The biggest fear that such a federation would bring about is the fear of a Korean bloc, or the disintegration of the precarious balance of power between the two parties in the US. Although partisans on both sides no doubt loathe that their side is even with the other in terms of influence and numbers, most Americans are very happy with the two party status quo (if they weren’t happy there would no longer be a two party status quo).

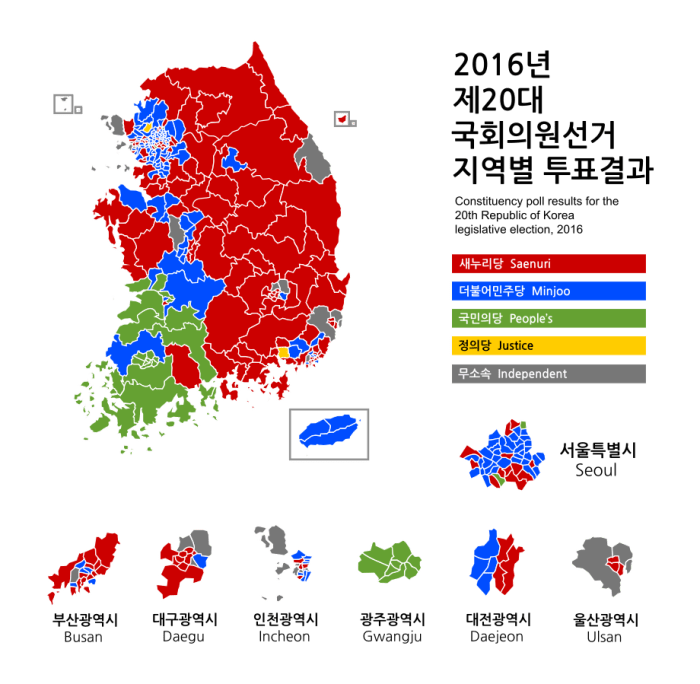

Admitting 5 to 7 new “states,” former Korean provinces, makes it seem like this delicate two party balance would be quickly destroyed with the advent of a Korean bloc which has no interest in traditional American politics. I assure you there would be no Korean bloc. Look at the most recent Korean elections:

There is a Left-Right divide focused on policy and to a lesser extent ideology rather than an ethnic one, just like here in the States.

The Korean Left would line up nicely with Democrats (it even has an anti-American streak that isn’t anti-American at all, only anti-GOP, just like the Democrats!). The conservative wing of South Korea might form a Korean bloc but it would be ineffective in the House and Senate because of its small number.

Libertarians are often dissatisfied with the status quo, even though they’re often the first to point out that life in Western states continues to get better and better. The status quo relationship between South Korea and the United States is great. But it could always be a little bit better.

Adam Smith on the character of the American rebels

They are very weak who flatter themselves that, in the state to which things have come, our colonies will be easily conquered by force alone. The persons who now govern the resolutions of what they call their continental congress, feel in themselves at this moment a degree of importance which, perhaps, the greatest subjects in Europe scarce feel. From shopkeepers, tradesmen, and attornies, they are become statesmen and legislators, and are employed in contriving a new form of government for an extensive empire, which, they flatter themselves, will become, and which, indeed, seems very likely to become, one of the greatest and most formidable that ever was in the world. Five hundred different people, perhaps, who in different ways act immediately under the continental congress; and five hundred thousand, perhaps, who act under those five hundred, all feel in the same manner a proportionable rise in their own importance. Almost every individual of the governing party in America fills, at present in his own fancy, a station superior, not only to what he had ever filled before, but to what he had ever expected to fill; and unless some new object of ambition is presented either to him or to his leaders, if he has the ordinary spirit of a man, he will die in defence of that station.

Found here. Today, many people, especially libertarians in the US, celebrate an act of secession from an overbearing empire, but this isn’t really the case of what happened. The colonies wanted more representation in parliament, not independence. London wouldn’t listen. Adam Smith wrote on this, too, in the same book.

Smith and, frankly, the Americans rebels were all federalists as opposed to nationalists. The American rebels wanted to remain part of the United Kingdom because they were British subjects and they were culturally British. Even the non-British subjects of the American colonies felt a loyalty towards London that they did not have for their former homelands in Europe. Smith, for his part, argued that losing the colonies would be expensive but also, I am guessing, because his Scottish background showed him that being an equal part of a larger whole was beneficial for everyone involved. But London wouldn’t listen. As a result, war happened, and London lost a huge, valuable chunk of its realm to hardheadedness.

I am currently reading a book on post-war France. It’s by an American historian at New York University. It’s very good. Paris had a large overseas empire in Africa, Asia, Oceania, and the Caribbean. France’s imperial subjects wanted to remain part of the empire, but they wanted equal representation in parliament. They wanted to send senators, representatives, and judges to Europe, and they wanted senators, representatives, and judges from Europe to govern in their territories. They wanted political equality – isonomia – to be the ideological underpinning of a new French republic. Alas, what the world got instead was “decolonization”: a nightmare of nationalism, ethnic cleansing, coups, autocracy, and poverty through protectionism. I’m still in the process of reading the book. It’s goal is to explain why this happened. I’ll keep you updated.

Small states, secession, and decentralization – three qualifications that layman libertarians (who are still much smarter than conservatives and “liberals”) argue are essential for peace and prosperity – are worthless without some major qualifications. Interconnectedness matters. Political representation matters. What’s more, interconnectedness and political representation in a larger body politic are often better for individual liberty than smallness, secession, and so-called decentralization. Equality matters, but not in the ways that we typically assume.

Here’s more on Adam Smith at NOL. Happy Fourth of July, from Texas.