- The subversive legacy of Christianity Helene Guldberg, spiked!

- Coronavirus in NJ: waiting for the surge Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- Thandika Mkandawire, RIP Isabel Ortiz, Jacobin

- The pandemic and the Will of God Ross Douthat, New York Times

Authoritarianism in Tiny Steps

All the power in both the County and the City of Santa Cruz (where I live) now resides in the hands of a County health official. Yesterday, she just closed all parks and all beaches in the county for at least a week. She had the courtesy to post a long letter explaining her reasons.

The letter contains this gem: “…too many of us were visiting the beach for leisure rather than recreation.”

I just can’t figure out the distinction. I am sure I don’t know when I am enjoying leisure from when I am recreating.

Now, I have been using the English language daily for about fifty-five years; it’s my working language; I write in it; I read at least a book a week in that language. Nevertheless, I don’t get the distinction. I even tried the old trick of translating the relevant phrase into my native language, French, like this:

Trop nombreux etaient ceux, entre nous qui se rendaient a la plage pour y jouir de leurs loisirs plutot que dans un but de recreation.

Still don’t know what the difference is!

The problem with George Orwell, the poor man’s libertarian theoretician, is that he keeps cropping up not matter how hard I try to shut him out of my mind. Way to go George! You were on to something.

Addendum the next day: I almost forgot. The county of Santa Cruz also explicitly forbade surfing (SURFING). Now, surfers hate even gliding past one another. They don’t congregate. They are sometimes suspected of attempting murder to get more space on the waves.

Two explanations come to mind for this strange interdiction. First, this is a devious way to stop many young people from nearby, very populated Silicon Valley to come over to Santa Cruz and enjoy their forced vacation on the waves. Or, second, this is an unconscious expression of the puritanism that always accompanies petty tyranny: Times are hard; you may not enjoy yourself, period!

Nightcap

- The era of peak globalization is over John Gray, New Statesman

- The world after coronavirus Yuval Harari, Financial Times

- A guide for the overwhelmed Bruce Frohnen, Modern Age

- Coordination problems in a post-pandemic world Peter Boettke, Coordination Problem

A Reflection on Information and Complex Social Orders

In the year 2020, occidental democracies face a time of lock-downs, social distancing, and a sort of central planning based on epidemiological models fueled by testing methodologies. An almost uniform consensus on the policy of “flattening the curve and raising the line” spread worldwide, both in the realms of politics and science. Since the said public policy is not for free, but nevertheless it is out of discussion, the majority of the efforts are focused on gathering data concerning the rate of infection and fatalities and on achieving accurate and fast methods of early detection of the disease (COVID-19). The more the data is collected, the more efficient the policy of “flattening the curve” will be, i.e.: minimizing the economical costs. Technology -in a broad sense- seems to be the key ingredient of every successful policy.

Nevertheless, since the countries that undertook the said task are democracies -and they were urged to do so because they are democracies-, there is a lot more than data provided by technology to take into account. Science and technology could reach a conclusive study about infection and fatality rates, but the outcomes of the societal discussions about the value of life and the right of every individual to decide upon the way of conducting their own plans of life will always remain inconclusive. Those discussions are not only philosophical and, fundamentally, are not only to be conducted in the terms of an academic research, since the values at stake entitle every human being to have their own say and, at the same time, are so deeply rooted in the upbringing of the individuals that seldom they might be successfully articulated -and surely that is why such questions are of philosophical interest.

In the race to determine the political agenda, technology plays with a significant advantage over philosophy: in times of emergency, conclusive assertions -despite proving right or wrong afterwards- enable political leaders with a sense of determination that any philosophy can hardly achieve. It is true that philosophical considerations mark the legitimate limits of science and its uses, but the predictable models and plausible scenarios depicted by the technology might lift the barriers of what had been considered at the time as politically illegitimate, i.e.: to describe a given situation as a state of exception.

However, there is still a dominion in which philosophical considerations might have high expectations of winning the competition against technology: the making of the abstract criteria to judge the fulfillment of the due procedures to be followed by the authorities given the account of the data gathered by the technology. Such philosophical considerations on which base authorities should personally account for their decisions, despite having been discussed by academics and writers, have being treated for centuries in particular legal procedures that crystallized the standards of conduct of the Civil Law (the diligence of a good father of a family, or of a good businessman, etc) or Common Law concepts (the reasonable person, the ordinary prudent man of business) or more recent -in terms of the evolution of the law- formulae, such as the Hand’s rule.

Such legal standards, concepts or formulae do not oblige the political authorities in their public sphere, but they perform as an incentive to be taken into account by the agent who is invested with the public authority; since he, eventually, will be personally accountable for his decisions. Moreover, those legal parameters to judge the personal responsibility of the agent in charge of the political authority are a true guarantee for the public servants, more reliable than the changing public opinion measurements to be provided by the technology.

Notwithstanding the Realist assertion about the division between law and politics might earn certain relevance in times of turmoil, individual rights and legal procedures should endure in the long run, in order to work as a benchmark to judge the personal performance of the political agents.

Such times of political and social upheaval are useful to test political theories and doctrines as well. Certain strains of Political Liberalism -particularly Classical Liberalism- have been largely criticized for -supposedly- trying to replace the political with the law. However, the law is there to remind the political agents that the state is an abstraction run by individuals who are expected to be personally accountable for their decisions. In this case, the true function of the law, although conceding that it should remain outside of the political sphere, is to provide the correct incentives for the political agents, who are not mere abstractions -and so, maximize their own plans- to take their own decisions. If technological devices might be the key instruments for public policy, the rule of law is its inescapable framework -or at least so it is, of course, for every democracy.

Everyone understands what your GPA this semester means

In my industry there’s been a ton of discussion about how to handle grading for this spring semester. Campuses shifted to online instruction mid-semester. Students are losing jobs, struggling with home responsibilities, and otherwise being utterly thrown into the deep end of an unfair situation.

Here’s the thing: we all get it. C+ this semester will be a mighty impressive accomplishment for a lot of students this year. Nobody looking at and subjectively interpreting a transcript will fail to appreciate that. If I’m looking at your transcript, I’m going to look at your GPA for before this and heavily discount this semester’s GPA if it’s anything different than it was in the fall.

For some students, this pandemic will be a minor hiccup, or even a chance to rise to the occasion and excel. Good for them. For other students, it will be such a significant disruption that they won’t be able to learn the material they’re ostensibly in school for. And if they can’t pass the class, that sucks. Pandemics suck, and their impact on people’s educational progress is part of that suckiness.

We absolutely should look for ways to reduce the impact on those students. We need to grant exceptions for things like scholarships requiring certain timelines and GPAs (like my favorite NY state program). But life happens, and a if grades are worth having at all (which we should debate), then we shouldn’t abandon them now. We should just abandon the stakes we’ve attached to them.

Damned Models and Cutting off the Chinese

I have a good eye for what ought to be there but isn’t. Don’t congratulate me; it’s a natural talent. I am retired so, I usually spend hours listening to the radio, reading newspapers and, watching television and, (Oops) on the internet. Nowadays, I do more of the same.

Today’s lecture is going to be a little longer than usual, on the one hand. On the other hand, there will not be a test. Bear with me; it’s going to be worth it (if I say so myself).

The first thing that’s missing from the endless and frankly a little sickening commentary on the C-virus epidemic is a good explanation of what’s a “model.” I mean the kind of models that are being blamed a little bit everywhere and especially in the conservative media for seemingly wildly inflated predictions (of infections, of deaths, of anything connected to this illness). Just from listening to talk radio, I think that some, or many, believe that with “computer models,” computers actually do the thinking instead of people. It’s not so.

The second thing missing is a clear description of the downside of national economic self-sufficency that appears so tempting now that we are extra-sensitive to both the comparative incompetence of our China-based suppliers, and to the possible ill-will of the Chinese Communist authorities.

First, first: a model is logically pretty much the same thing as we do when we say, ” On the one hand, on the other hand.” That’s as in, “One the on hand, If have saved $20, I will buy a nice cake; on the other hand, if I manage to save $200, I will look for a good used bike.”

The problems are: 1 that we have only so many hands; if we had one hundred each, and remembered each, we could produce mental models that cover more possibilities; 2 that we are not agile at combining possibilities, like this: “If the third hand and the fortieth hand are combined with the fifty-first then, this will happen.”

Models – designed by humans working slowly – can be entered into computers with many values and many combinations of values to tell us what would (WOULD) happen if… That’s all, folks.

Don’t blame the models, don’t blame those who build the models, in this capacity, rather, blame those who don’t do the needful to explain to decision-makers what actual models do and don’t do. (It’s true that they are often the same as those who actually construct the models but in a different role.)

Also, blame American universities and colleges that should have been in the business of teaching this stuff to all students since the late sixties and that have only done it for a tiny elite minority. A big missed opportunity. Even high school students could learn, I believe.

Second undiscussed issue. Under normal circumstances, self-sufficiency has a certain intuitive appeal: Let’s not count on others because they might fail, or fail us and, at any rate, distance makes the best linkages vulnerable. Now that we worry about running out of essential medical supplies made in China, now that we fear a shortage of the raw materials that go into our medical drugs, our intuition seems broadly vindicated. It did not help that a highly placed Chinese Communist official actually threatened the US aloud, about a month ago, with withholding medications. (I am guessing he is not going to have a happy retirement.)

Much about our intuition is correct, of course. As I never tire of stating (wittily, if you ask me), we should not count on steel deliveries from China to build the naval ships we would use in a war with China. The steel deliveries might be too late.

That’s on the one hand. On the other hand, there is a downside to national self-sufficiency. It violates the general principle that specialization makes for efficiency. Just imagine that you had to grow all your own grain, harvest it, mill it, raise your own cattle, slaughter it, butcher it, skin it, preserve the meat, treat the skins (and cut and sew clothes out of them). You would do a bad job of some of these tasks, at least, possibly of all. You would have much less to consume than is true now. You would be poor.

And that’s the downside: National self sufficiency is a sure path to poverty. I am not speaking of small differences but of big ones. I remember clearly when the cheapest hammer at the hardware store cost $20, five years later, the cheapest hammer cost only $5. What happened in between was expanded imports from China. (Don’t even begin to talk about quality; the difference among the cheapest items of a kind is largely illusory anyway, or much exaggerated.) And if you think this is a special case, ask your self if the Canadians – who love bananas – should grow their own in the name of self-sufficiency.* (For an expanded view of international trade, see my series of articulated short essays beginning here: “Protectionism; Free Trade, Step-by-Step.”)

Here again, American colleges and universities deserve strong blame. First, many don’t even require a course in economics to graduate. One of the best undergraduates I have known personally, an honors students who is now very successful in her career, never heard a single lecture on anything pertaining to economics. Second, economics professors, by and large, do a piss-poor job of teaching international trade. Across 25 years of teaching in a business school, I have met a fair number of good MBA students who had taken three courses in international trade and still did not see the possible downside of self-sufficiency. So, this simple idea is not widespread among the educated populace. It’s not well anchored enough in the opinion media for many to push back intelligently against the wave of demands that the US minimize its dependency on what we obtain from abroad in general. (A national policy designed to induce American companies to source in Vietnam, for example, rather than in China is a different and defensible proposition.)

So, here you have it: Models are not to blame, confusion about them is; economic self-sufficiency is the road to poverty though it might be worth it. Knowing these two things does not prevent us from taking action collectively. It makes for more rational action in these irrational times.

* Those of you who received a decent education in economics might wonder here if I have just dealt improperly with the topic of Comparative Advantage. I haven’t, I have not even begun.

Nightcap

- Life after the plague Helen Dale, Law & Liberty

- Believing in witches and demons Jan Machielsen, JHIblog

- What comes next? Dalibor Rohac, American Interest

- Modi’s ghastly Delhi dream Kapil Komireddi, Critic

Be Our Guest: “Rights and Government Confiscation During COVID-19”

John A Lancaster has a new guest post up. Peep an excerpt of his definition of rights:

When extended into the realm of human contact, rights must be expressed through voluntary exchange. Any exchange that is not the product of consent necessarily entails an entity seizing use of facilities outside the entity’s personal vessel, which they have no right to do (theft).

Click here to read the thought-provoking rest. And don’t forget: if you’ve got something to say, and nowhere to say it, Be Our Guest!

Coddle the Old, Spoil Them; Everybody Else, Back to Work!

I am more worried by the day about the economic consequences of the current isolation policy intended to change the shape (not the numbers) of the corona-virus epidemic in America. This, in spite of the a large infusion of (national debt) money, that I would approve regretfully if it were my sole decision. (Note: I am not an economist but I have been reading the Wall Street Journal daily for thirty years. I am also a scholar of organizations including businesses.) What inspires most of my fear is that the issue of small-scale entrepreneurship is seldom discussed, as if it did not exist.

I believe that the larger businesses, those that survive the current crisis, may well come back with a roar (as the president seems to predict for the whole US economy.) The problem is that small businesses, restaurants, but also dry cleaning establishments, hair dressers, bookstores, and the like, have short financial lifelines. Many must be dying like flies, right now. It will be difficult or impossible for them to make a comeback once the health emergency is gone. Also we can’t count on fast replacement of those failed business by new entrepreneurs. The collection of small business that accrued over many years at a particular location is not going to be replaced in the course of a few months, I think. (Yes, I know something about this topic. Ask me.)

All the above, in spite of large infusion of my granddaughter’s money by the federal department. (She is 11.) And, repeating myself, I would do it too if it were my decision, but regretfully.

The ruinous strategy of idling much of the workforce could have been avoided and could still be modified quickly, it seems to me. The alternative solution would be to confine all the sick and most of the aged, and to keep children out of school (because they are veritable cesspools, as everyone knows).

Everyone else would be invited to go back to work by agreement with his employer. Some financial dispositions should be offered at state’s expense to help parents who lose income because they must stay home to care for their children. Under such conditions, the economy would grow again and many irreplaceable small businesses would survive. Sweden is currently trying something like this policy. That country never ordered most people to stay home. I hope this experiment stays in the news. It may not because the liberal media are afraid of rational responses and of responses that don’t proceed from panic.

I only know two people who have consistently advocated for an American policy and a California policy of confining only the old and the sick. The two are myself and Jimmy Joe Lee, a singer composer musician from Boulder Creek, near Santa Cruz. Both of us are old dudes. We are both close to the center of virus’ target. I am 78 and Jimmy Joe may be even slightly older. (OK, let the whole truth come out: He is taller, straighter than I am and a much, much sharper dresser.) I am just pointing to the obvious: neither of us is speaking out of selfishness.

Now, let’s imagine the old are confined from, say, the age of 65, even 60. First, some of them wouldn’t even know anything has changed because they don’t go out much anyway. For the rest of us, all you would have to do is serve us promptly two hot meals a day. They would have to be of gourmet quality. That would be easy to achieve because so many expensive restaurants are idle and hurting. It would be a nice touch if the meals were brought and served by a youngish woman wearing a short skirt. We may not remember why we like it but we do. Yes, and speaking for myself and I am sure, for Jimmy Joe, don’t forget to send along each meal a couple of glasses of really, really good old wine. I assure you that however extravagant you went with that last component of our confinement regimen, it would be a lot cheaper than what you are currently doing. At least, promise to think about it.

Nightcap

- When arguments fail (a response to libertarians) Irfan Khawaja, Policy of Truth

- State-sponsored empire building (philanthropy) Edward Carver, LARB

- How airpower reshaped the global diplomatic order Thomas Furse, Age of Revolutions

- The friendly Mr Wu Mara Hvistendahl, 1843

Nightcap

- Colin Powell: subordinate or statesman? Elizabeth Spalding, Law & Liberty

- Another right abolished by the government’s COVID lockdown Ryan McMaken, Power & Market

- “All our efficiencies melted away in the face of a man-made depression.” Razib Khan, City Journal

- Bread Arrives Patrick Henry, Commonweal

Mass Hysteria and the Great Economy-Killing: Lessons from 1856 South Africa

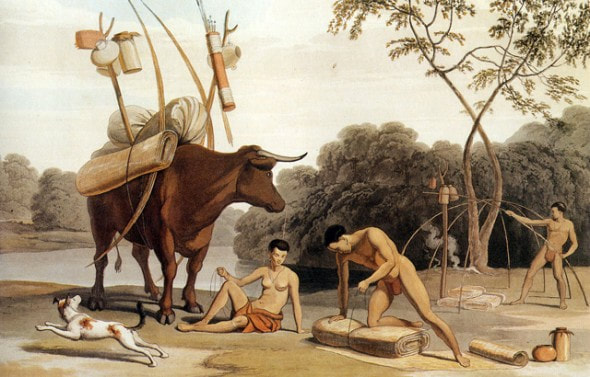

In 1856, a teenage Xhosa girl Nongqawuse (1841-1898) had a prophetic vision that spread like a fire among that nation that resided in South Africa. The prophecy came amid a lung virus infection that spread among some Xhosa stock; it was rumored that the sickness came from the imported European cattle. In her vision, which the girl duly delivered to her people, two spirits of ancestors had visited her and ordered Xhosa people to destroy all their cattle, corn, tools and foods. The spirits insisted that these had been all contaminated. In return, the ancestors would bring the dead back to life, drive away the hated British, and launch the paradise on the earth, which was to bring the limitless supply of food, stock, and household items.

The spirits also “ordered” people not to do any work but to wait and see the fulfillment of the prophecy. At first, some Xhosa skeptics laughed at this, but soon when her uncle, a powerful and charismatic witchdoctor Mhalakaza, vouched for her and validated the prophecy by his expert opinion, people took it seriously, especially after all powerful chiefs sided with the uncle. In fact, by killing his own cattle, Mhalakaza set a personal example. The supreme chief Sarili added to this his own spin by insisting that, besides the cattle slaughter, all European clothing should be ditched because it was unclean. He insisted that his people, indigenous in their “naked attire” and coated in red clay, were “clean” compared to the whites who wore clothes. Moreover, the “doctor” set a deadline for the paradise to materialize. It was to happen at the end of 1856 on a day of a full moon.

Society became divided into “believers” and “non-believers” who were a minority. The greater part of the Xhosa became agitated and followed the command of the superior forces by slaughtering over 400,000 cattle and destroying their food supplies along with other “contaminated” items. They also decided to sow no crops for future. When on the designated day of the full moon no miracle arrived, fearing for his life, Mhalakaza disappeared. From his hideout he had a message sent to the people that the spirits were angry with the Xhosa who did not slaughter all their stock. For this reason, the fine new cattle did not emerge from the ground and the dead did not resurrect. Within twelve months, with about 100,000 people starving themselves to death, the Xhosa population dropped by 80%. For more about the Xhosa stock “pandemic” craze, see Jeffrey Brian Peires, The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle-Killing Movement of 1856-1857 (Johannesburg and Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1989).

The state as the illusionary Deus Ex Machina

The 20th century was a century in which societies consolidated the belief that governments should provide certainty and protection from collective risks and developed the expectation that governments are well equipped to do so through large-scale interventions in the social environment.

The image of the state was transformed from that of an alien and often hostile apparatus in the service of the king and nobility to that of a collective organization entrusted with society’s safety and prosperity. This view grew stronger in the years of war-like economy and post-war reconstruction during the 21st century. Nationalism gave it the face of a father taking care of his extended family. Socialism gave it the image of a collective machine serving the interests of the working class. Democracy promised to tame its power, make it accountable to its subjects and harness it for the provision of public goods, whose definition was open to public deliberation.

The image of the state was also shaped by a growing belief in the use of science to give meaning to the ‘common good’ and offer prescriptions as to how a powerful central planner should work to achieve it. The state and science together provided a replacement for the loss of divinity. They offered a rationalization of power as enlightened parenthood. They created a secular Deus Ex Machina. Governments cultivated this paradigm as they were strengthening their role and clout over society through increasing levels of taxation, regulation and distribution, which in turn fostered public expectations for state effectiveness and political accountability. Recurrent failures led to policy re-adjustments some of which were historical political transitions. Yet all these transitions were responses that complied with this paradigm and sought to re-establish confidence in it.

Consider one of the most discussed economic and political transitions, the neoliberal turn. In light of recurrent economic crises, most prominently long-standing stagflation in the 1970s, neoliberalism best describes a re-adjustment of the role of government in the economy through privatizations, a drift away from Keynesianism to monetarism, and the re-regulation of economic structure. In the field of ideology, there was an effort to reshape public perceptions of what the state should not do with the promotion of economic freedom. Governments – most of them very reluctantly, such as both the Conservative and Labour governments in the late 1970s and the Ford and Carter administrations, while others very enthusiastically such as the Reagan and Thatcher governments – adopted versions of a ‘take some economic decisions back to you’ approach.

In the so-called neoliberal era, the state did not become less interventionist overall. Instead, governments redefined the nature of interventions in some areas to forms of surveillance of the responsibilities and individual risks that were given back to businesses and workers. Neoliberalism was a large-scale intervention in itself. It was an effort to revamp the economy and protect the capacity of states to extract resources from the market for political allocation. Governments preserved interventions that privileged the few and maintained those that continued to offer a safety net for the many (such as health insurance, progressive taxation and welfare state spending).

A remarkable juncture occurred when the 2009 crisis posed a systemic threat. Governments intervened to patch the financial system from a sequence of cascading events – partly the result of imbalances attributed to its own macroeconomic policies. The management of collective risk came center stage.

Terrorism is another case of the interventionist state. Spectacular terrorist attacks triggered a war-like response that combined the use of the criminal justice system with extra-judicial actions, including the mobilization of security and military forces and the introduction of new intrusive norms of intelligence collection and surveillance.

It is easy to discern that, over time, demand for drastic state action is more pronounced in the presence of dramatic single-source events or cascading events that are traceable as a single sequence. While millions are killed by car accidents and diseases, large-scale massacres such as the 9/11 or unravelling developments from the collapse of a major bank trigger a collective alarm. The public expects the state to intervene and give a heroic fight against the visible threat on behalf of society.

The most extreme version of the protective state is the current general lockdown. Not knowing any way out, governments can only deliver a form of collective protection that requires a general population quarantine. They offer society the kind of shield that a medieval wall and a locked gate offers in times of siege. Society both expects and accepts this.

Yet in the current pandemic governments still cannot deliver a cure. If a safe vaccine is not found, if the epidemic does not recede with growing immunity, if seasonal change doesn’t make any difference with contagion and if an effective anti-viral treatment is not found, governments will oversee their economies in rapid collapse and will soon have to make tough choices about how to turn the epidemic into a chronic manageable condition. For the time being, citizens remain disciplined in their lock-down and are the ones demanding strict measures. Governments know that, like in terrorism, citizens can be overwhelmed by fear as well as managed through fear.

In our efforts to understand what has happened and to make informed guesses about what could happen, metaphors can help or distort our perception. Societies have subscribed to an ideal image of political power that metaphorically resembles the biblical God: omnipotent, omniscient and benevolent. They call for a divine intervention, they express their dissatisfaction when they see no signs of it but they never question its raison d’ être. But there is an ontologically different metaphor. In Greek mythology gods are superhuman creatures struggling for domination and survival with their own moral regards, vices and ignorance as they mess around with the world of humans. They struggle to rule based more on terror than wisdom, imposing justice that serves their order. Humans have to worship them in order to appease them. I find this imagery closer to a realist depiction of government.

Religious speech gets shorted again

Today, the U.S. Supreme Court denied a petition asking whether a transit authority can reject a Christmas ad for display on its buses just because the ad is religious. This is an easy question, and it’s a shame the Court denied the petition. Justices Gorsuch and Thomas, though, did write a short consolation prize, saying what they would have said if they granted the case: namely, the government can’t discriminate against a religious viewpoint on a topic while allowing other non-religious viewpoints.

The sides of buses are a frequent and heated battleground for free speech. Transit authorities often draw revenue by selling blank space on their buses. In this case, Archdiocese of Washington v. Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority, the Catholic Church tried to place a Christmas ad on D.C. buses with the silhouettes of a few shepherds and the phrase “Find the Perfect Gift.” The transit authority rejected the ad.

The key fact here was that the transit authority allowed other ads about Christmas. All the parties, and the various courts, agreed that Christmas has a “secular” component and a “religious” component. Hence, Wal-Mart and Macy’s and every other retailer could slap their ads on buses across the metropolitan area clamoring about how to celebrate the holiday (by buying their stuff). But a religious advertiser could not express their views on how to celebrate the holiday in that same space, the only difference being the religious nature of the content.

The Supreme Court has repeatedly stated in other settings that similar restrictions constitute viewpoint discrimination. If the government allows speech on a particular subject matter, it cannot then restrict speech on that topic simply because the viewpoint is religious. That’s true even if the proposed speech drips with religious sentiment–such sentiment deserves equal footing under the First Amendment.

This isn’t to say that D.C. buses can now be overrun with religious zealotry. D.C. could lawfully limit advertisements to only commercial ads (they don’t). And of course they could always just forego the revenue and say no ads at all. But if the government opens up a space for expression, it must do so even-handedly.

Nightcap

- Behind the Iron Curtain: Soviet space art (gallery) Kadish Morris, Guardian

- The year I left the Soviet Union Alex Halberstadt, New Yorker

- Free speech, libel, and privacy rights Mark Hemmingway, RealClearPolitics

- 8 out of 10 Texans already live in cities and metropolitan areas Steven Pedigo, Dallas Morning News